United States sanctions

United States sanctions are imposed against countries that violate the interests of the United States. Sanctions are used with the intent of damaging another country's economy in response to unfavorable policy or decisions.[1] The United States has imposed two-thirds of the world's sanctions since the 1990s.[2] Numerous American unilateral sanctions against various countries around the world have been criticized by different commentators. It has imposed economic sanctions on more than 20 countries since 1998.[3]

History

After the failure of the Embargo Act of 1807, the federal government of the United States took little interest in imposing embargoes and economic sanctions against foreign countries until the 20th century. United States trade policy was entirely a matter of economic policy. After World War I, interest revived. President Woodrow Wilson promoted such sanctions as a method for the League of Nations to enforce peace.[4] However, he failed to bring the United States into the League and the US did not join the 1935 League sanctions against Italy.[5]

Trends in whether the United States has unilaterally or multilaterally imposed sanctions have changed over time.[6] During the Cold War, the United States led unilateral sanctions against Cuba, China, and North Korea.[6] Following the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, United States sanctions became increasingly multilateral.[6] During the 1990s, the United States imposed sanctions against countries it viewed as rogue states (such as Zimbabwe, Yugoslavia, and Iraq) in conjunction with multilateral institutions such as the United Nations or the World Trade Organization.[6] According to communications studies academic Stuart Davis and political scientist Immanuel Ness, in the 2000s, and with increasing frequency in the 2010s, the United States acted less multilaterally as it imposed sanctions against perceived geopolitical competitors (such as Russia or China) or countries that, according to Davis and Ness, were the site of "proxy conflicts" (such as Yemen and Syria).[6]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet and some members of the United States Congress asked the United States to suspend its sanctions regimes as way to help alleviate the pandemic's impact on the people of sanctioned countries.[7] Members of Congress who argued for the suspension of sanctions included Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Ilhan Omar.[8]

The United States applies sanctions more frequently than any other country or nation, and does so by a wide-margin.[9] According to American Studies academic Manu Karuka, the United States has imposed two-thirds of the world's sanctions since the 1990s.[2] Collectively, the nations that are subject to some kind of U.S. sanction make up little more than one fifth of the world's GDP. Eighty percent of that group comes from China.[10]

Types of sanctions imposed by the United States

- bans on arms-related exports,[11]

- controls over dual-use technology exports,

- restrictions on economic assistance, and

- financial restrictions such as:

- requiring the United States to oppose loans by the World Bank and other international financial institutions,

- diplomatic immunity waived, to allow families of terrorism victims to file for civil damages in U.S. courts,

- tax credits for companies and individuals denied, for income earned in listed countries,

- duty-free goods exemption suspended for imports from those countries,

- authority to prohibit U.S. citizens from engaging in financial transactions with the government on the list, except by license from the U.S. government, and

- prohibition of U.S. Defense Department contracts above $100,000 with companies controlled by countries on the list.[12]

- Visa designations that prevent from entering the U.S.

Targeted parties

By 2021, the U.S. has sanctioned more than 9,000 individuals, companies, and sectors of the economy of target countries, according to the U.S. Treasury Department.[13]

Countries

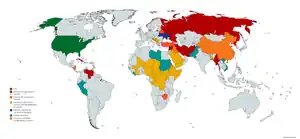

As of November 2022, the United States has sanctions against:[14]

| Country | Year introduced | Article | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | North Korea–United States relations and sanctions against North Korea | Severe sanctions justified by extreme human rights abuses by North Korea and the North Korean nuclear program. North Korea and the US currently have no diplomatic relations.

Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report which imposes ban on participating in International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and Foreign Military Sales (FMS)[15] | |

| 1958 | Cuba–United States relations and United States embargo against Cuba | Reasons cited for the embargo include Cuba's poor human rights record. Since 1992, the UN General Assembly has regularly passed annual resolutions criticizing the ongoing impact of the embargo imposed by the United States. | |

| 1979 (lifted 1981), reintroduced 1987[lower-alpha 1] | Iran–United States relations and United States sanctions against Iran | Near total economic embargo on all economic activities began in 1979; in response to the storming of U.S. Embassy in Tehran by Iranian Revolutionaries, precipitating a hostage crisis involving dozens of American diplomats. Though lifted in 1981, significant sanctions were again imposed in 1987 and rapidly expanded in the late 2010s due to the Iranian Nuclear Program and Iran's poor human rights record. Iran and the US have no diplomatic relations. Iran is listed as state sponsor of terrorism.

Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report which imposes ban on participating in International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and Foreign Military Sales (FMS)[15] | |

| 1986 | Syria–United States relations and sanctions against Syria | Reasons cited include Syria's poor human rights record, the Civil War, and being listed as a state sponsor of terrorism. Syria and the US have had no diplomatic relations since 2012.

Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report which imposes ban on participating in International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and Foreign Military Sales (FMS)[15] | |

| 2019[lower-alpha 2] | United States–Venezuela relations and International sanctions during the Venezuelan crisis[16] | Reasons cited for sanctions include Venezuela's poor human rights record, links with illegal drug trade, high levels of state corruption and electoral rigging.

Since 2019, Venezuela and the United States have no diplomatic relations under president Nicolás Maduro.[17] Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report which imposes ban on participating in International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and Foreign Military Sales (FMS)[15] | |

| 2022 | Russia–United States relations and sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War | On April 20, Transkapitalbank, located in Russia, and a ring of more than 40 individuals and businesses overseen by Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev are named as being involved in sanction violations. Executives with ties to Russia's Otkritie Financial Corp. Bank are among those named.

On May 8, Announces new sanctions against Russia, targeting executive board members of Sberbank and members of Gazprombank JSC. The latest sanctions target JSC Bank Moscow Industrial Bank. In addition, three of Russia's most prominent state-owned and controlled television networks have been sanctioned: JSC Channel One Russia, television station Russia-1, and JSC NTV Broadcasting Co. The measure is aimed at preventing the sale of equipment to broadcasters and advertising revenue generated in the United States. |

Persons

| Polity | Description |

|---|---|

| Certain persons the US government believes to be undermining democratic processes or institutions in Belarus (including President Alexander Lukashenko and other officials).

Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report. However Belarus is subject to some certain exemptions.[15] | |

| the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned two Cambodian government officials, Chau Phirun (Chau) and Tea Vinh (Tea), for their roles in corruption in Cambodia.[18] | |

| Persons the US government believes contribute to the conflict in the Central African Republic.

Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report which imposes ban on participating in International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and Foreign Military Sales (FMS).[4] | |

| Persons whom the US government believes are committing Genocide against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang and persons whom the US government believes are committing human rights abuses in Hong Kong and Tibet.

Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report which imposes ban on participating in International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and Foreign Military Sales (FMS)[15] Since 2020, Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act.[19] | |

| Certain persons the US government believes are contributing to the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. | |

| Certain persons the US government believes are involved in the Ethiopian war, such as armed forces and government officials.[20] | |

| Imposing Sanctions on Certain Persons with Respect to the Humanitarian and Human Rights Crisis in Ethiopia[21] | |

| Persons the US government believes undermine Hong Kong's autonomy. This implements provision of the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act of 2019 and the Hong Kong Autonomy Act of 2020 as well as executive order no. 13936. | |

| Specific individuals and entities associated with the former Ba'athist regime of Saddam Hussein, as well as parties the US government believes have committed, or pose a significant risk of committing acts of violence that threaten the peace or stability of Iraq, undermine efforts to promote economic reconstruction and political reform in Iraq, or make it more difficult for humanitarian workers to operate in Iraq. | |

| Persons the US government believes undermine the sovereignty of Lebanon or its democratic processes and institutions. | |

| Sanctions Liberia’s former warlord and current senator Prince Johnson.[22] | |

| Persons contributing to the Conflict in Mali including Government officials tied to Wagner Group such as Malian Defense Minister Colonel Sadio Camara, Air Force Chief of Staff Colonel Alou Boi Diarra, and Deputy Chief of Staff Lieutenant Colonel Adama Bagayoko[23] | |

| Persons the US government believes undermine the sovereignty, stability and the democratic processes and institutions of Moldova.[24] | |

| Officials associated with the Rohingya crisis[25] and the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état.[26][27]

Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report which imposes ban on participating in International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and Foreign Military Sales (FMS).[15] | |

| Persons associated with contributing to the repression of the 2018–2020 Nicaraguan protests.[28] | |

| Persons believed to be responsible for the detention, abuse, and death of Sergei Magnitsky and other reported violations of human rights in Russia (see Magnitsky Act of 2012). Since 2014, International sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War, since 2017 Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act.

Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report which imposes ban on participating in International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and Foreign Military Sales (FMS).[15] | |

| Certain persons the US government believes are contributing to the conflict in Somalia. | |

| Persons the US government alleges have contributed to the conflict in South Sudan or committed human rights abuses.

Country listed as Tier 3 on Trafficking in Persons Report which imposes ban on participating in International Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and Foreign Military Sales (FMS).[15] | |

( |

Persons the US government believes undermine the peace, security, stability, territorial integrity and the democratic processes and institutions of Ukraine. Also persons administering areas of Ukraine without central government consent, also a number of Russian senior officials who are close to Vladimir Putin. |

| Persons who the US government believes are contributing to the ongoing crisis in Venezuela. | |

| Persons who the US government claims threaten peace, security, or stability in Yemen. | |

| Persons the US government believes undermine democratic processes or institutions in Zimbabwe, including a number of Government Officials. |

Some of the countries which are listed are members of the World Trade Organization, but WTO rules allow trade restrictions for non-economic purposes.

Combined, the Treasury Department, the Commerce Department and the State Department list sanctions concerning these countries or territories:

War in Ukraine

As of February 2022, following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the United States has sanctions against:

Russia

Targeted Russian elites:[29]

- Sergei Borisovich Ivanov

- Andrey Patrushev

- Nikolai Platonovich Patrushev

- Igor Ivanovich Sechin

- Alexander Aleksandrovich Vedyakhin

- Andrey Sergeyevich Puchkov

- Yuriy Alekseyevich Soloviev

- Galina Olegovna Ulyutina

Belarus

Leader of Synesis Group:[30]

- Aliaksandr Yauhenavich Shatrou

Belarusian Defense Officials:[30]

- Viktor Khrenin

- Aleksandr Grigorievich Volfovich

- Aliaksandr Mikalaevich Zaitsau

Minor Sanctions

While sanctions were placed, these countries have only minor targets in terms of sanctions.

| Polity | Description |

|---|---|

| Certain persons affiliated with the elite paramilitary force, RAB, along with the force itself, the US government believes to be committing serious human rights violations.[31][32] | |

| The U.S. State Departament imposed visa restrictions on Georgian court Chairmen and members of the High Council of Justice of Georgia under Section 7031(c) of the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2023, barring them and their immediate family members from entering the U.S. for supposed involvement in "significant corruption". The judges criticized the decision as an attempt to subjugate the Georgian court system to foreign control.[33] | |

| After the purchase of a Russian-made S-400 air defense system, the US place anticipated sanctions on the Turkish Ministry of Defense and Presidency of Defense Industries (SSB)[34][35] |

Former sanctions

| Polity | Description |

|---|---|

| Persons who the US government claims threaten peace, security, or stability in Burundi.

Sanctions lifted on November 18 2021.[36] |

Perceptions

Since 1990, the use of sanctions by the United States has significantly increased, and since 1998, the US has established economic sanctions on more than 20 countries.[3]

A series of studies led by economist Gary Hafbauer has found destabilization of the sanctioned country is the frequent goal of US sanctions programs.[37] Destabilization occurs when people in the sanctioned country lose confidence in their government's ability to operate the country and viable alternatives for them to consider exist.[37]

According to Daniel T. Griswold, sanctions failed to change the behavior of sanctioned countries but they have barred American companies from economic opportunities and harmed the poorest people in the countries under sanctions.[38] Secondary sanctions,[lower-alpha 3] according to Rawi Abdelal, often separate the US and Europe because they reflect US interference in the affairs and interests of the European Union (EU).[39] Abdelal said since Donald Trump became President of the United States, sanctions have been seen as an expression of Washington's preferences and whims, and as a tool for US economic warfare that has angered historical allies such as the EU.[40]

Criticisms of efficacy

The increase in the use of economic leverage as a US foreign policy tool has prompted a debate about its usefulness and effectiveness.[41] According to Rawi Abdelal, sanctions have become the dominant tool of statecraft of the US and other Western countries in the post-Cold War era. Abdelal stated; "sanctions are useful when diplomacy is not sufficient but force is too costly".[42] British diplomat Jeremy Greenstock said sanctions are popular because "there is nothing else [to do] between words and military action if you want to bring pressure upon a government".[43] Former CIA Deputy Director David Cohen wrote: "The logic of coercive sanctions does not hold, however, when the objective of sanctions is regime change. Put simply, because the cost of relinquishing power will always exceed the benefit of sanctions relief, a targeted state cannot conceivably accede to a demand for regime change."[44]

Most international relations scholarship concludes sanctions almost never lead to overthrow of sanctioned countries' governments or compliance by those governments.[45] More often, the outcome of economic sanctions is the entrenchment in power of state elites in the sanctioned country.[45] In a study of US sanctions from 1981 to 2000, political scientist Dursan Peksen found sanctions have been counterproductive, failing to improve human rights and instead leading to a further decrese in sanctioned countries' "respect for physical integrity rights, including freedom from disappearances, extrajudicial killings, torture, and political imprisonment".[46] Economists Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliot state while policymakers often have high expectations of the efficacy of sanctions, there is at most a weak correlation between economic deprivation and the political inclination to change.[47] Griswold wrote sanctions are a foreign policy failure, having failed to change the political behavior of sanctioned countries; they have also barred American companies from economic opportunities and harmed the poorest people in the sanctioned countries.[38] A study by the Peterson Institute for International Economics said sanctions have achieved their goals in fewer than 20% of cases. According to Griswold, as an example, the US Nuclear Proliferation Prevention Act of 1994 could not stop Pakistan and India from testing nuclear weapons.[38]

Political scientist Lisa Martin criticized a game theory view of sanctions, stating proponents of sanctions characterize success so broadly—applying it to a range of outcomes from "renegotiation" to "influencing global public opinion—the terminology of "winning" and "losing" overextends those concepts.[48]

Humanitarian criticisms

Daniel T. Griswold of the Cato Institute criticizes sanctions from a conservative Christian perspective, writing sanctions limit the possibilities of a sanctioned country's people to exercise political liberties and practice market freedom.[49] In 1997, the American Association for World Health stated the US embargo against Cuba contributed to malnutrition, poor water access, and lack of access to medicine and other medical supplies; it concluded "a humanitarian catastrophe has been averted only because the Cuban government has maintained a high level of budgetary support for a health care system designed to deliver primary and preventative medicine to all its citizens".[50]

Economist Helen Yaffe estimates United States sanctions against Venezuela have caused the deaths of 100,000 people due to the difficulty of importing medicine and health care equipment.[50]

According to journalist Elijah J Magnier in Middle East Eye, the West—led by America and Europe—had not sent any immediate aid to Syria after the 2023 Turkey–Syria earthquake. According to Magnier, some mainstream media incorrectly stated President Bashar al-Assad was preventing humanitarian aid from reach the Turkish-occupied northwestern provinces of Syria and border crossings. According to one Western diplomat; "the goal is to get the Syrian people to blame their president for western countries’ refusal to provide aid".[51]

Isolation of the United States and its markets

According to Abdelal, US sanctions on its own internal economy cost almost nothing but overuse of them could be costly in the long term. Abdelal said the biggest threat is the US's gradual isolation and the continuing decline of US influence in the context of an emerging, multi-polar world with differing financial and economic powers.[52] Abdelal also said the US and Europe largely agree on the substance of sanctions but disagree on their implementation. The main issue is secondary US sanctions—also known as extraterritorial sanctions—[53]which prohibit any trading in US dollars and prevent trade with a country, individuals and organizations under the US sanctions regime.[39] Primary sanctions restrict US companies, institutions, and citizens from doing business with the country or entities under sanctions.[53] According to Abdelal, secondary sanctions often separate the US and Europe because they reflect US interference in the EU's affairs and interests. Increasing use of secondary sanctions increases their perception in the EU as a violation of national and EU sovereignty, and an unacceptable interference in the EU's independent decision-making.[39] Secondary sanctions imposed on Iran and Russia are central to these tensions,[42] and have become the primary tool for signaling and implementing secession from US and European political goals.[53]

In 2019, the United States Department of State reported it received complaints from American telecommunications providers and television companies the sanctions against Cuba caused difficulties in incorporating the country into their grid coverage.[54]

De-dollarization efforts

Retired business-studies academic Tim Beal views the US's imposition of financial sanctions as a factor increasing dedollarization efforts because of responses like the Russian-developed System for Transfers of Financial Messages (SPFS), the China-supported Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), and the European Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) that followed the US's withdrawal of from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran.[9]

Historian Renate Bridenthal wrote; "the most looming blowback to US sanctions policy is the growing set of challenges to dollar hegemony". Bridenthal cited the use of local currencies to trade with sanctioned countries, and attempts by Russia and China to increase the gold backing of their respective currencies.[55]

Sanctions as measures against opposition

Farrokh Habibzadeh of the Iranian Petroleum Industry Health Organization wrote a letter to The Lancet comparing the strategy of sanctions to besieging in ancient times, when armies that could not conquer a city that was surrounded by defensive walls would besiege the city to prevent access by residents to necessary supplies.[56] According to Hufbauer, Schott and Elliot (2008), regime change is the most-frequent foreign policy objective of economic sanctions, accounting for around 39% of cases of their imposition.[57]

Cuba

There have been 29 consecutive nearly unanimous United Nations General Assembly resolutions demanding the US end its embargo of Cuba.[58] When the US imposed its embargo in 1961, Cuba did most of its commerce with the US. Griswold said since then, the sanctions had no effect on Fidel Castro's government, which used sanctions to justify the failure of policies and to attract international compassion. Griswold said although the sanctions formerly had international backing, as of 2000, no other country supported them. Pope John Paul II stated during his visit to Cuba embargoes "are always deplorable because they harm the needy".[38]

Iran

In May 2018, the US government announced its withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and launched a maximum pressure campaign against Iran, which resulted in public protests, and reproach from European political and business elites.[59] Excessive use of US financial sanctions has worried companies, and prompted many EU member states and institutions to limit the exposure of their economies to the US-based clearing system that creates extreme vulnerability for countries other than the US.[60] The Trump administration reintroduced sanctions against Iran with an executive order, going against the wishes of many politicians.[61] In March 2023, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen announced the US was looking for ways to strengthen its sanctions against Iran.[62]

Iraq

In 1990, the Iraqi Army invaded and occupied Kuwait; the invasion was met with international condemnation and brought immediate sanctions against Iraq.[63] The effects of sanctions on the population of Iraq have been disputed. The figure of 500,000 child deaths was widely cited for a long period but in 2017, research showed the figure was the result of survey data manipulated by the Saddam Hussein government. Three surveys conducted since 2003 all found the child mortality rate between 1995 and 2000 was approximately 40 per 1,000, meaning there was no major rise in child mortality in Iraq after sanctions were implemented.[64]

Economic engagement as an alternative

According to Denis Halliday, sanctions in Iraq forced people to depend on the Iraqi government for survival and further reduced the likelihood of a constructive solution. He commented:

We have saved [the regime] and missed opportunities for change ... if the Iraqis had their economy, had their lives back, and had their way of life restored, they would take care of the form of governance that they want, that they believe is suitable to their country.[65]

Implementing agencies

- Bureau of Industry and Security

- Directorate of Defense Trade Controls

- Office of Foreign Assets Control

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection

- United States Department of Commerce (Export Administration Regulations, EAR)

- United States Department of Defense

- United States Department of Energy (nuclear technology)

- United States Department of Homeland Security (border crossings)

- United States Department of Justice (including ATF and FBI)

- United States Department of State (International Traffic in Arms Regulations, ITAR)

- United States Department of the Treasury

Authorizing laws

Several laws delegate embargo power to the President:

- Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917[66]

- Foreign Assistance Act of 1961[66]

- International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977

- Export Administration Act of 1979

Several laws specifically prohibit trade with certain countries:

- Cuban Assets Control Regulations of 1963

- Cuban Democracy Act of 1992[66]

- Helms–Burton Act of 1996 (Cuba)[66]

- Iran and Libya Sanctions Act of 1996

- Trade Sanction Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000 (Cuba)[66]

- Iran Freedom and Support Act of 2006

- Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010

Footnotes

- Temporarily lifted in 1981 during Iran–Iraq War, re-introduced in 1987

- In August 2019, President Donald Trump announced further sanctions on Venezuela, ordering a freeze on all Venezuelan government assets in the United States and barred transactions with US citizens or companies. Part of the ongoing Venezuelan presidential crisis which started in January 2019.

- Secondary US sanctions prohibit any trading in US dollars and prevent trade with a country, individuals or organizations under the US sanctions regime.[39]

See also

- State Sponsors of Terrorism (U.S. list) – placement on the list puts severe restrictions on trade with that nation

- Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List

- United States sanctions against China

- Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act

- Rogue state

- Economic sanctions

- 2002 United States steel tariff

- Permanent normal trade relations

- Arms Export Control Act

- United States and state terrorism

- Criticism of United States foreign policy

- European Union Sanctions

References

Citations

- Haidar, J.I., 2017."Sanctions and Exports Deflection: Evidence from Iran," Economic Policy (Oxford University Press), April 2017, Vol. 32(90), pp. 319-355.

- Manu Karuka (December 9, 2021). "Hunger Politics: Sanctions as Siege Warfare". Sanctions as War. BRILL. pp. 51–62. doi:10.1163/9789004501201_004. ISBN 9789004501201. S2CID 245408284.

- Gordon, Joy (March 4, 1999). "Sanctions as Siege Warfare". The Nation.

- "Evidence on the Costs and Benefits of Economic Sanctions". PIIE. March 2, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- Strang, G. Bruce (2008). ""The Worst of all Worlds:" Oil Sanctions and Italy's Invasion of Abyssinia, 1935–1936". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 19 (2): 210–235. doi:10.1080/09592290802096257. S2CID 154614365. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Strategy. 2023. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

- Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Strategy. 2023. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

- "Bernie Sanders and AOC call on US to lift Iran sanctions as nation reels from coronavirus". The Independent. April 1, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- Tim Beal (December 9, 2021). "Sanctions as Instrument of Coercion: Characteristics, Limitations, and Consequences". Sanctions as War. BRILL. pp. 27–50. doi:10.1163/9789004501201_003. ISBN 9789004501201. S2CID 245402040.

- Sabatini, Christopher (2023). "America's Love of Sanctions Will Be Its Downfall". Foreign Policy.

- Haidar, J.I., 2017."Sanctions and Exports Deflection: Evidence from Iran," Economic Policy (Oxford University Press), April 2017, Vol. 32(90), pp. 319-355.

- "Chapter 3: State Sponsors of Terrorism". Country Reports on Terrorism 2009. United States Department of State. August 5, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Sabatini, Christopher (2023). "America's Love of Sanctions Will Be Its Downfall". Foreign Policy.

- "Sanctions Programs and Country Information". United States Department of the Treasury. March 9, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Staff, B. B. N. (November 30, 2018). "US cuts aid to Belize over Human Trafficking Tier 3 ranking".

- "Venezuela: Overview of U.S. sanctions" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Federation of American Scientists. March 8, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- Meredith, Sam (May 21, 2018). "US likely to slap tough oil sanctions on Venezuela — and that's a 'game changer' for Maduro". CNBC. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- "Treasury Targets Corrupt Military Officials in Cambodia". U.S. Department of the Treasury. June 27, 2023. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- "Trump signed a law to punish China for its oppression of the Uighur Muslims. Uighurs say much more needs to be done". Business Insider. June 30, 2020.

- "US sanctions Eritrean military over role in Tigray conflict".

- https://ofac.treasury.gov/sanctions-programs-and-country-information/ethiopia

- "U.S. Sanctions Liberia's former warlord and senator Prince Johnson". The Hindu. December 10, 2021.

- https://www.state.gov/imposing-sanctions-on-malian-officials-in-connection-with-the-wagner-group/

- "Treasury Targets Corruption and the Kremlin's Malign Influence Operations in Moldova". October 26, 2022.

- "US sanctions Myanmar military over Rohingya ethnic cleansing". ABC News. August 17, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- "US sanctions on Myanmar: 5 things to know". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- "Burma-Related Sanctions".

- Koran, Laura (July 5, 2018). "US slaps new sanctions on Nicaragua over violence, corruption". CNN. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- "Russia-related Designations; Belarus Designations; Issuance of Russia-related Directive 2 and 3; Issuance of Russia-related and Belarus General Licenses; Publication of new and updated Frequently Asked Questions". U.S. Department of the Treasury. February 24, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- "U.S. Treasury Targets Belarusian Support for Russian Invasion of Ukraine". U.S. Department of the Treasury. February 24, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- "Global Magnitsky Designations; North Korea Designations; Burma-related Designations; Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies (NS-CMIC) List Update". U.S. Department of the Treasury. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Riaz, Ali (December 16, 2021). "US sanctions on Bangladesh's RAB: What happened? What's next?". Atlantic Council. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- "STATEMENT BY SECRETARY ANTONY J. BLINKEN: Public Designations of Mikheil Chinchaladze, Levan Murusidze, Irakli Shengelia, and Valerian Tsertsvadze, Due to Involvement in Significant Corruption". U.S. Embassy in Georgia official website. April 6, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- "U.S. sanctions NATO ally Turkey over Russian defense system". NBC News.

- Pompeo, Mike The United States Sanctions Turkey Under CAATSA 231 US Department of State

- https://www.state.gov/termination-of-burundi-sanctions-program/

- Hafbauer, Gary (2023). Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Strategy. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

- Griswold, Daniel. "Going Alone on Economic Sanctions Hurts U.S. More than Foes". CATO Institute. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011.

- Abdelal 2020, p. 118.

- Abdelal 2020, p. 133.

- Lenway 1988, p. 397.

- Abdelal 2020, p. 114.

- Marcus, Jonathan (July 26, 2010). "Analysis: Do economic sanctions work?". BBC News. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Strategy. 2023. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

- Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Strategy. 2023. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

- Peksen, Dursun (2009). "Better or Worse? The Effect of Economic Sanctions on Human Rights". Journal of Peace Research. 46 (1): 59–77. doi:10.1177/0022343308098404. ISSN 0022-3433. S2CID 110505923.

- Hufbauer, Gary Clyde; Schott, Jeffrey J.; Elliott, Kimberly Ann; Oegg, Barbara (2007). Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. Peterson Institute. p. 162. ISBN 9780881325362.

- Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Strategy. 2023. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

- Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Strategy. 2023. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

- Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Strategy. 2023. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

- Magnier, Elijah J (February 10, 2023). "Turkey-Syria earthquake: Aid gap reveals western double standards". Middle East Eye.

- Abdelal 2020, p. 134.

- Abdelal 2020, p. 117.

- Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Strategy. 2023. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

- Renate Bridenthal (December 9, 2021). "Blowback to US Sanctions Policy". Sanctions as War. BRILL. pp. 323–332. doi:10.1163/9789004501201_020. ISBN 9789004501201. S2CID 245394028.

- Habibzadeh, Farrokh (2018). "Economic sanction: a weapon of mass destruction". The Lancet. 392 (10150): 816–817. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31944-5. PMID 30139528. S2CID 52074513.

- Hufbauer, Gary Clyde; Schott, Jeffrey J.; Elliott, Kimberly Ann; Oegg, Barbara (2008). Economic Sanctions Reconsidered (3 ed.). Washington, DC: Columbia University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780881324822. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

By far, regime change is the most frequent foreign policy objective of economic sanctions, accounting for 80 out of the 204 observations.

- "UN General Assembly calls for US to end Cuba embargo for 29th consecutive year". UN News. June 23, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- Abdelal 2020, pp. 114–115.

- Abdelal 2020, p. 130.

- Abdelal 2020, p. 131.

- Lawder, David; Singh, Kanishka (March 23, 2023). "Yellen: Iran's actions not impacted by sanctions to the extent US would like". Reuters.

- Peters, John E; Deshong, Howard (1995). Out of Area or Out of Reach? European Military Support for Operations in Southwest Asia (PDF). RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-2329-2.

- Dyson, Tim; Cetorelli, Valeria (July 24, 2017). "Changing views on child mortality and economic sanctions in Iraq: a history of lies, damned lies and statistics". BMJ Global Health. 2 (2): e000311. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000311. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 5717930. PMID 29225933.

- Chomsky 2003, p. 93.

- Sanctions as War: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on American Geo-Economic Policy. 2023. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-64259-812-4. OCLC 1345216431.

Sources

- Abdelal, Rawi; Bros, Aurélie (2020). "The End of Transatlanticism?: How Sanctions Are Dividing the West". Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development. Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development. 16 (16): 114–135. JSTOR 48573754.

- Lenway, Stefanie Ann (1988). "Between war and Commerce: economic sanctions as a tool of statecraft". International Organization. Cambridge University Press. 42 (2): 397–426. doi:10.1017/S0020818300032860. S2CID 154337246.

Further reading

| Library resources about United States sanctions |

- Hufbauer, Gary C. Economic sanctions and American diplomacy (Council on Foreign Relations, 1998) online.

- Hufbauer, Gary C., Jeffrey J. Schott, and Kimberley Ann Elliott. Economic Sanctions Reconsidered: History and Current Policy (Washington DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 1990)

- Mulder, Nicholas. The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War (2022) also see online review

External links

- Sanctions Programs and Country Information (United States Department of the Treasury)

- Commerce Control List (Bureau of Industry and Security)