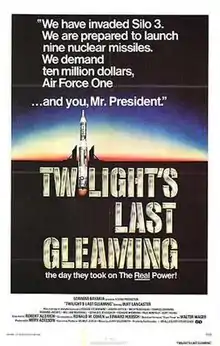

Twilight's Last Gleaming

Twilight's Last Gleaming is a 1977 thriller film directed by Robert Aldrich and starring Burt Lancaster and Richard Widmark. The film was a West German/American co-production, shot mainly at the Bavaria Studios.

| Twilight's Last Gleaming | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Robert Aldrich |

| Screenplay by | Ronald M. Cohen Edward Huebsch |

| Based on | Viper Three 1971 novel by Walter Wager |

| Produced by | Merv Adelson |

| Starring | Burt Lancaster Roscoe Lee Browne Joseph Cotten Melvyn Douglas Charles Durning Richard Jaeckel William Marshall Gerald S. O'Loughlin Richard Widmark Paul Winfield Burt Young |

| Cinematography | Robert B. Hauser |

| Edited by | Michael Luciano William Martin Maury Winetrobe |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Allied Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 146 min |

| Countries | United States West Germany |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6.2 million[1] |

| Box office | $4.5 million[2] |

Loosely based on a 1971 novel, Viper Three by Walter Wager, it tells the story of Lawrence Dell, a renegade USAF general who escapes from a military prison and takes over an ICBM silo in Montana, threatening to launch the missiles and start World War III unless the President reveals a top secret document to the American people about the Vietnam War.

A split screen technique is used at several points in the movie to give the audience insight into the simultaneously occurring strands of the storyline. The film's title, which functions on several levels, is taken from "The Star-Spangled Banner", the national anthem of the United States:

- O say can you see, by the dawn's early light, / What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming?

Plot

After escaping from a military prison, rogue Air Force General Lawrence Dell and accomplices Powell, Garvas, and Hoxey infiltrate a Montana ICBM complex that Dell helped design. Their goal is to gain control over its nine Titan nuclear missiles. The infiltration does not go as planned, as the impulsive Hoxey guns down an Air Force guard for trying to answer a ringing phone. Dell then shoots and kills Hoxey. The three then make direct contact with the US government (avoiding any media attention) and demand a $10 million ransom and that the President go on national television and make public the contents of a top-secret document.

The document, which is unknown to the current president but not to certain members of his cabinet, contains conclusive proof that the US government knew there was no realistic hope of winning the Vietnam War but continued fighting for the sole purpose of demonstrating to the Soviet Union their unwavering commitment to defeating Communism.

Meanwhile, Dell and his two remaining men remove the security countermeasures to the launch control system and gain full control over the complex.

While the President and his Cabinet debate the practical, political, personal, and ethical aspects of agreeing to the demands, they also authorize the military to send an elite team led by General MacKenzie to penetrate the ICBM complex and incinerate its command center with a low-yield tactical nuclear device. Just as the device is about to be set, the commando team accidentally trips an alarm, alerting Dell to their operation. A furious Dell responds by initiating the launch sequence for all nine missiles. As the military and President Stevens watch the underground missile silo launch covers begin to open, they agree to call off the attempt and the launch is aborted with mere seconds to spare. During this time, the captive Air Force guards attempt to overpower Dell and his men, resulting in the death of Garvas and another guard.

Eventually, the President agrees to meet the demands, which include allowing himself to be taken hostage and used as a human shield while Dell and Powell make their escape from the complex. As the President leaves the White House, he asks the Secretary of Defense to release the document should he be killed in the process. US Air Force snipers take aim and shoot both Dell and Powell, but also accidentally shoot the President, who with his dying breath asks the Secretary of Defense if he will release the document. The Secretary cannot bring himself to answer.

Cast

- Burt Lancaster as General Lawrence Dell

- Richard Widmark as General Martin MacKenzie

- Charles Durning as President David Stevens

- Melvyn Douglas as Secretary of Defense Guthrie

- Joseph Cotten as Secretary of State Renfrew

- Paul Winfield as Willis Powell

- Burt Young as Augie Garvas

- Richard Jaeckel as Lieutenant Colonel Sandy Towne

- Roscoe Lee Browne as James Forrest

- William Marshall as Attorney General Klinger

- Gerald S. O'Loughlin as Brigadier General O'Rourke

- Leif Erickson as Ralph Whittaker

- Charles Aidman as Bernstein

- Charles McGraw as Air Force General Crane

- William Smith as Hoxey

- Simon Scott as General Phil Spencer

- Morgan Paull as First Lieutenant Louis Cannellis

- Bill Walker as Willard

- David Baxt as Sergeant Willard

- Glenn Beck as Lieutenant

- Ed Bishop as Major Fox

- Phil Brown as Reverend Cartwright

- Gary Cockrell as Captain Jackson

- Don Fellows as General Stonesifer

- Weston Gavin as Lieutenant Wilson

- Garrick Hagon as Alfie, The Driver

- Elizabeth Halliday as Stonesifer's Secretary

- David Healy as Major Winters

- Thomasine Heiner as Nurse Edith

- William Hootkins as Sergeant Fitzpatrick (as Bill Hootkins)

- Ray Jewers as Sergeant Domino

- Ron Lee as Sergeant Rappaport

- Robert Sherman as Major LeBeau

- John Ratzenberger as Sergeant Kopecki

- Robert MacLeod as State Trooper Chambers

- Lionel Murton as Colonel Horne

- Robert O'Neil as Briefing Officer

- Shane Rimmer as Colonel Alexander B. Franklin

- Pamela Roland as Sergeant Kelly

- Mark Russell as Airman Mendez

- Rich Steber as Captain Kincaid

- Drew W. Wesche as Lieutenant Witkin

- Kent O. Doering as Barker

- Allan Dean Moore as Sperling, Sharpshooter

- M. Phil Senini as Sharpshooter

- Rick Demarest as Sparrow

- Gary Harper as Air Force Sergeant Andy Keen

Production

Development

Viper Three by Walter Wager was published in 1971. Film rights were purchased that year by Lorimar Productions.[3]

Lorimar were known for making TV series like The Waltons and Eight is Enough and TV movies like Sybil and Helter Skelter. They wanted to move into feature film production and Twilight's Last Gleaming—as it would be known—would be their first.[4]

According to Aldrich, Lorimar "couldn't get it [a film of the novel] financed. Every actor in town had seen it—including Burt Lancaster... If you hadn't already seen it, you were going to see it. Or you knew one or two pictures that were kind of like it... There was no social impact. The kidnappers had no interesting motivation. The reasons they wanted to get the President weren't even PLO-type reasons. They just wanted the money. That didn't seem to me to make much sense."[5]

Lorimar took the project to Aldrich, who said he "wondered what would happen if you had an Ellsberg mentality, if you had some command officer who came out of Vietnam and who was soured not by war protestors but by the misuse of the military... What would happen if you had a general who was angry at the political use of the armed forces?"[5]

Aldrich told Lorimar he would do the film "if I could turn that story upside down".[5] Aldrich pitched his take on the material to Burt Lancaster, who agreed to do the film.

Lancaster called the film "All the President's Men Part Two... a very powerful political piece couched in highly melodramatic terms".[6]

Financing

Lorimar took the project to a German company who agreed to put up two thirds of the budget. The finance came from German tax shelter money.[7]

Merv Adelson, head of Lorimar, described the movie as "the perfect formula picture... an action-adventure picture that appeals to the international market. Pre sell it to television and abroad. Have all our money back before it opens domestically."[8]

Adelson would later become disillusioned with this formula because the films did not achieve much critical acclaim, and if they did not perform domestically Lorimar did not make that much money out of them.[8]

Casting

Lancaster and Aldrich thought the President could be a John F. Kennedy type. Lancaster approached Paul Newman to play the role, but he was not enthusiastic. So, Aldrich reconfigured the character as a Mayor Daley type politician.[5]

Script

The writers Ronald M. Cohen and Edward Huebsch wrote the script together over six weeks. Aldrich called it "the most unlikely marriage in the world. Huebsch's a little wizened old man, sixty-two, sixty-three years old, been in the political wars for forty years, probably the most knowledgeable political analyst in town - or at least up there with Abe Polonsky and Ring Lardner. And Cohen is a loud-mouthed, extroverted, young, smart-ass guy who knows that he votes Democratic... an extraordinarily gifted writer in terms of what people say and how they say it.[5] The script was originally 350 pages.

"If that movie's anti-American so is Jimmy Carter," said Aldrich. "The most inflammatory statement in the movie is that it opts for open government."[9]

Split Screen

Aldrich decided to use split screen and multiple panels. "I don't particularly like panels unless they're in a bread commercial. But I thought they fitted that particular movie. They cost me an extra half a year - half a year. But you couldn't tell that story in less than three hours without them."[5]

Aldrich normally used Joseph Biroc as cinematographer but Biroc's wife fell ill before shooting so Aldrich used Robert Hauser.

Filming

Filming took place in Munich in August 1976.

Several scenes were shot with Vera Miles as the president's wife but were cut to save time.[5]

Aldrich said he hoped the audience came to realise that the Lancaster character was crazy. "But I don't think we did it. The audience is so much for those guys getting away with it." He also did not feel it was ambiguous enough at the end as to whether the shooting of the president was intentional.[5]

Reception

James Monaco wrote that Twilight's Last Gleaming "don't do much but play with paranoia".[10]

Release

The film did poorly at the box office.

In France it recorded admissions of 88,945.[11]

It was unsuited for videocassettes, because the split-screen effects do not work well in low resolution of that format. After the rights reverted to the film's German co-producers, a major remastering effort was done by Bavaria Media, who released a Blu-ray edition, distributed in the United States by Olive Films and Eureka Video in the United Kingdom.[12]

See also

- Seven Days in May also stars Burt Lancaster as an Air Force general and ringleader of a group of U.S. Military leaders plotting a coup against the President.

References

- Alain Silver and James Ursini, Whatever Happened to Robert Aldrich?, Limelight, 1995 p 300

- Alain Silver and James Ursini, Whatever Happened to Robert Aldrich?, Limelight, 1995 p 42

- Widmark in 'Legends' Role Murphy, Mary. Los Angeles Times 31 July 1971: a9.

- FILM CLIPS: Sci-Fi in De Palma's Future Kilday, Gregg. Los Angeles Times 15 Aug 1977: e8.

- "I CAN'T GET JIMMY CARTER TO SEE MY MOVIE!" Aldrich, Robert. Film Comment; New York Vol. 13, Iss. 2, (Mar/Apr 1977): 46-52.

- A Bittersweet Burt Lancaster, Looking Back-and Forward--at 62: A Bittersweet Burt Lancaster By Kenneth Turan. The Washington Post 23 May 1976: 165.

- Lorimar a Hollywood Hit: Lorimar a Hollywood Hit 20 Percent Foreign Funds 'Not Suited' to Go Public By PAMELA G. HOLLIE New York Times 8 Mar 1980: 27

- Small Movie Companies Gamble for 'One Big Hit': $50 Million Tied Up Depend on Distributors Different Kinds of Movies Fears for the Future By ALJEAN HARMETZ New York Times 21 Mar 1981: 11.

- A Touch of Garbo for 'Fedora' Kilday, Gregg. Los Angeles Times 28 Mar 1977: e7.

- Monaco, James (1979). American Film Now. p. 285.

- French box office results for Robert Aldrich films at Box Office Story

- David Kehr (November 25, 2012). "Nuclear Missiles and Cold War Cupid's Arrows". New York Times.