Tuknanavuhpi

Tuknanavuhpi' is a two-player abstract strategy board game played by the Hopi Native American Indians of Arizona, United States.[1] It is also played in many parts of Mexico.[2] The game was traditionally played on a slab of stone with the board pattern etched on it.[1] Tukvnanawopi resembles draughts and Alquerque.[2] Players attempt to capture each other's pieces by hopping over them.[1] It is not known when the game was first played; however, the game was published as early as 1907 in Stewart Culin's book Games of the North American Indians Volume 2: Games of Skill.[1]

A similar game (with a similar name) also played by the Hopi is Tukvnanawopi. The only differences are that in Tuknanavuhpi lines of intersection points become unplayable as opposed to rows or columns of squares in Tukvnanawopi, and that in Tukvnanawopi there can be two or four players.[1][3] (A more elaborate description is provided in the Game Play and Rules section.) Another similar game called Aiyawatstani is played by the Keres Native American tribe in New Mexico.[3] Additionally, the game is also similar to Kharbaga from Africa, which may suggest a historical connection.

Objective

The object of the game is to capture all of the opponent's pieces. The player who does so wins.[4]

Equipment

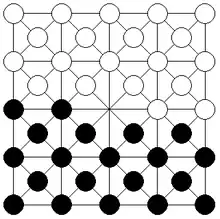

A 4×4 square board is used. Left and right leaning diagonal lines run through each square. This accounts for 41 intersection points.[2] Each player has 20 pieces called pokmoita, which means animals. Each set of 20 pieces is discernible from the other, generally by color. The design of pieces varies, with common variants including grains of maize or black and white stones.[3][4]

Gameplay and rules

- Players decide who will play with which color pieces. White (or the lighter of two colors) goes first.[1]

- Each player's 20 pieces are set up on his or her half of the board on the intersection points including the middle (fifth) rank, specifically the two intersection points to the left of the middle point. The middle point is the only intersection point left vacant in the beginning.[2]

- Players alternate their turns. Each turn consists of a player selecting just one of his or her pieces and performing either a single move or one or more captures. A player may not perform both a move and a capture in a single turn.

- A move consists of relocating a piece from one intersection point along a line in any direction to an adjacent intersection point, so long as the destination intersection point is vacant. At the start of play, the first player must move a piece to the middle point as it is the only vacant intersection point.[2] After performing a move, the player's turn is over.

- A capture consists of a player using a piece to "hop" over an opponent's piece that lies on an adjacent intersection point in any direction, and "landing" on a vacant intersection point along that same line and immediately proceeding the hopped-over opponent's piece. The piece that is hopped over is thus captured and removed from the board. Only one piece may be hopped over at a time. If, after performing a capture, the player is able to make another capture using the same piece and without having to execute a move, he or she may do so, and may continue to do so until no further capture opportunities are available for that piece, at which point the turn ends.[1][2]

- Although it is the object of the game to capture all of an opponent's pieces, executing a particular capture — while it may be legally possible — may prove strategically unwise. There is no indication from available sources that performing a capture is required simply because it is executable. However, it would appear that during one's turn, one must perform at least one legal action, whether a move or a capture. "The player who goes first moves a piece into the empty space and the opponent jumps over and captures it."[2] Because the only legal action to start the game is a move, the first player must do so. Because the only legal action the opponent may follow with is a capture, he or she must do so.

- When a line of intersection points (row or column) on one end of the board becomes empty during the course of the game, pieces can no longer be played on that line of intersection points.[1] It is uncertain, however, if a row or column of intersections points within a row or column of squares is considered to be a "line of intersection points". No specific source clarifies this for now.

- As the game progresses, another line of intersection points (row or column) on one end of the board will eventually become empty, and therefore unplayable. The playing area of the board continues to shrink during the course of the game.[1]

See also

- Tukvnanawopi

- Aiyawatstani

- Kharbaga

- Alquerque

- Draughts

References

- Culin, Stewart (January 1992). Games of the North American Indians: Games of skill. pp. 794–795. ISBN 9780803263567. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- Leibs, Andrew (2004). Sports and games of the Renaissance. pp. 116–117. ISBN 9780313327728. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- "Native American Technology and Art: Native American Board Games". Tara Prindle. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- "Tuknanavuhpi". deskovehry.info. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

External links

- Games of the North American Indians By Stewart Culin ISBN 0-486-23125-9, ISBN 978-0-486-23125-9