Tsilhqotʼin language

Nenqayni Chʼih (lit. "the Native way") (also Chilcotin, Tŝilhqotʼin, Tsilhqotʼin, Tsilhqútʼin) is a Northern Athabaskan language spoken in British Columbia by the Tsilhqotʼin people.

| Chilcotin | |

|---|---|

| Tŝinlhqutʼin | |

| Pronunciation | [ts̠ˤʰᵊĩɬqʰotʼin] |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | Chilcotin Country, Central Interior of British Columbia |

| Ethnicity | 4,350 Tsilhqotʼin (2014, FPCC)[1] |

Native speakers | 860 (2014, FPCC)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | clc |

| Glottolog | chil1280 |

| ELP | Tsilhqot'in (Chilcotin) |

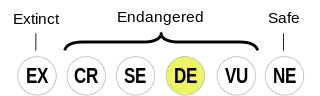

Chilcotin is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

| People | Tŝilhqotʼin |

|---|---|

| Language | Tŝilhqotʼin Chʼih |

| Country | Tŝilhqotʼin Nen |

The name Chilcotin is derived from the Chilcotin name for themselves: Tŝilhqotʼin literally "people of the red ochre river".

Phonology

Consonants

Chilcotin has 47 consonants:

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | sibilant | lateral | plain | labial | plain | labial | ||||||

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n̪ ⟨n⟩ | ||||||||||

| Occlusive | tenuis | p ⟨b⟩ | t̪ ⟨d⟩ | ts̪ ⟨dz⟩ | tɬ ⟨dl⟩ | ts̱ˤ ⟨dẑ⟩ | tʃ ⟨j⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ | kʷ ⟨gw⟩ | q ⟨gg⟩ | qʷ ⟨ggw⟩ | ʔ ⟨ʔ⟩ |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨p⟩ | t̪ʰ ⟨t⟩ | ts̪ʰ ⟨ts⟩ | tɬʰ ⟨tl⟩ | ts̱ˤʰ ⟨tŝ⟩ | tʃʰ ⟨ch⟩ | kʰ ⟨k⟩ | kʷʰ ⟨kw⟩ | qʰ ⟨q⟩ | qʷʰ ⟨qw⟩ | ||

| ejective | t̪ʼ ⟨tʼ⟩ | ts̪ʼ ⟨tsʼ⟩ | tɬʼ ⟨tlʼ⟩ | ts̱ˤʼ ⟨tŝʼ⟩ | tʃʼ ⟨chʼ⟩ | kʼ ⟨kʼ⟩ | kʷʼ ⟨kwʼ⟩ | qʼ ⟨qʼ⟩ | qʷʼ ⟨qwʼ⟩ | |||

| Continuant | voiceless | s̪ ⟨s⟩ | ɬ ⟨lh⟩ | s̱ˤ ⟨ŝ⟩ | ç ⟨sh⟩ | xʷ ⟨wh⟩ | χ ⟨x⟩ | χʷ ⟨xw⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | |||

| voiced | z̪ ⟨z⟩ | l ⟨l⟩ | ẕˤ ⟨ẑ⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | w ⟨w⟩ | ʁ ⟨r⟩ | ʁʷ ⟨rw⟩ | |||||

- Like many other Athabaskan languages, Chilcotin does not have a contrast between fricatives and approximants.

- The alveolar series is pharyngealized.

- Dentals and alveolars:

- Both Krauss (1975) and Cook (1993) describe the dental and alveolar as being essentially identical in articulation, postdental, with the only differentiating factor being their different behaviours in the vowel flattening processes (described below).

- Gafos (1999, personal communication with Cook) describes the dental series as apico-laminal denti-alveolar and the alveolar series as lamino-postalveolar.

Vowels

Chilcotin has 6 vowels:

| Front | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tense-long | lax-short | tense-long | lax-short | tense-long | lax-short | |

| High | i ⟨i⟩ | ɪ ⟨ɨ⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | ʊ ⟨o⟩ | ||

| Low | æ ⟨a⟩ | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | ||||

- Chilcotin has both tense and lax vowel phonemes. Additionally, tense vowels may become lax from vowel laxing.

Every given Chilcotin vowel has a number of different phonetic realizations from complex phonological processes (such as nasalization, laxing, flattening). For instance, the vowel /i/ can be variously pronounced [i, ĩ, ɪ, e, ᵊi, ᵊĩ, ᵊɪ].

Tone

Chilcotin is a tonal language with two tones: high tone and low tone.

Phonological processes

Chilcotin has vowel flattening and consonant harmony. Consonant harmony (sibilant harmony) is rather common in the Athabaskan language family. Vowel flattening is unique to Chilcotin but is similar to phonological processes in other unrelated Interior Salishan languages spoken in the same area, such as Shuswap, Stʼátʼimcets, and Thompson River Salish (and thus was probably borrowed into Chilcotin). That type of harmony is an areal feature common in this region of North America. The Chilcotin processes, however, are much more complicated.

Vowel nasalization and laxing

Vowel nasalization is a phonological process by which the phoneme /n/ is nasalizes the preceding vowel. It occurs when the vowel + /n/ sequence is followed by a (tautosyllabic) continuant consonant (such as /ɬ, sˤ, zˤ, ç, j, χ/).

/pinɬ/ → [pĩɬ] 'trap'

Vowel laxing is a process by which tense vowels (/i, u, æ/) become lax when followed by a syllable-final /h/: the tense and lax distinction is neutralized.

/ʔɛstɬʼuh/ → [ʔɛstɬʼʊh] 'I'm knitting' (u → ʊ) /sɛjæh/ → [sɛjɛh] 'my throat' (æ → ɛ)

Vowel flattening

Chilcotin has a type of retracted tongue root harmony. Generally, "flat" consonants lower vowels in both directions. Assimilation is both progressive and regressive.

Chilcotin consonants can be grouped into three categories: neutral, sharp, and flat.

| Neutral | Sharp | Flat | |

|---|---|---|---|

p, pʰ, m |

ts, tsʰ, tsʼ, s, z |

sˤ-series: | tsˤ, tsʰˤ, tsʼˤ, sˤ, zˤ |

| q-series: | q, qʰ, qʼ, χ, ʁ | ||

- Flat consonants trigger vowel flattening.

- Sharp consonants block vowel flattening.

- Neutral consonants do not affect vowel flattening in any way.

The flat consonants can be further divided into two types:

- a sˤ-series (i.e. /tsˤ, tsʰˤ, tsʼˤ/ˌ etc.), and

- a q-series (i.e. /q, qʷ, qʰ/ˌ etc.).

The sˤ-series is stronger than the q-series by affecting vowels farther away.

This table shows both unaffected vowels and flattened vowels:

| unaffected vowel |

flattened vowel |

|---|---|

| i | ᵊi or e |

| ɪ | ᵊɪ |

| u | o |

| ʊ | ɔ |

| ɛ | ə |

| æ | a |

The vowel /i/ surfaces as [ᵊi] if after a flat consonant and as [e] before a flat consonant:

/sˤit/ → [sˤᵊit] 'kinɡfisher' (sˤ flattens i → ᵊi) /nisˤtsˤun/ → [nesˤtsˤon] 'owl' (sˤ flattens i → e)

The progressive and regressive flattening processes are described below.

Progressive flattening

In the progressive (left-to-right) flattening, the q-series consonants affect only the immediately following vowel:

/ʁitʰi/ → [ʁᵊitʰi] 'I slept' (ʁ flattens i → ᵊi) /qʰænɪç/ → [qʰanɪç] 'spoon' (qʰ flattens æ → a)

Like the q-series, the stronger sˤ-series consonants affects the immediately following vowel. However, it affects the vowel in the following syllable as well if the first flattened vowel is a lax vowel. If the first flattened is tense, the vowel of the following syllable is not flattened.

/sˤɛɬ.tʰin/ → [sˤəɬ.tʰᵊin] 'he's comatose' (sˤ flattens both ɛ → ə, i → ᵊi ) /sˤi.tʰin/ → [sˤᵊi.tʰin] 'I'm sleeping' (sˤ flattens first i → ᵊi, but not second i: *sˤᵊitʰᵊin)

Thus, the neutral consonants are transparent in the flattening process. In the first word /sˤɛɬ.tʰin/ 'he's comatose', /sˤ/ flattens the /ɛ/ of the first syllable to [ə] and the /i/ of the second syllable to [ᵊi]. In the word /sˤi.tʰin/ 'I'm sleeping', /sˤ/ flattens /i/ to [ᵊi]. Since, however, the vowel of the first syllable is /i/, which is a tense vowel, the /sˤ/ cannot flatten the /i/ of the second syllable.

The sharp consonants, however, block the progressive flattening caused by the sˤ-series:

/tizˤ.kʼɛn/ → [tezˤ.kʼɛn] 'it's burning' (flattening of ɛ is blocked by kʼ: *tezˤkʼən) /sˤɛ.kɛn/ → [sˤə.kɛn] 'it's dry' (flattening of ɛ is blocked by k: *sˤəkən)

Regressive flattening

In regressive (right-to-left) harmony, the q-series flattens the preceding vowel.

/ʔælæχ/ → [ʔælaχ] 'I made it' (χ flattens æ → a) /junɛqʰæt/ → [junəqʰat] 'he's slappinɡ him' (qʰ flattens ɛ → ə)

The regressive (right-to-left) harmony of the sˤ-series, however, is much stronger than the progressive harmony. The consonants flatten all preceding vowels in a word:

/kunizˤ/ → [konezˤ] 'it is lonɡ' (zˤ flattens all vowels, both i → e, u → o) /kʷɛtɛkuljúzˤ/ → [kʷətəkoljózˤ] 'he is rich' (zˤ flattens all vowels, ɛ → ə, u → o) /nækʷɛnitsˤɛ́sˤ/ → [nakʷənetsˤə́sˤ] 'fire's gone out' (tsˤ, sˤ flatten all vowels, æ → a, ɛ → ə)

Both progressive and regressive flattening processes occur in Chilcotin words:

/niqʰin/ → [neqʰᵊin] 'we paddled' /ʔɛqʰɛn/ → [ʔəqʰən] 'husband'

References

- Chilcotin at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

External links

Bibliography

- Andrews, Christina. (1988). Lexical Phonology of Chilcotin. (unpublished M.A. thesis, University Of British Columbia).

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Clements, G. N. (1991). A Note on Chilcotin Flattening. (unpublished manuscript).

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1976). A Phonological Study of Chilcotin and Carrier. A Report to the National Museums of Canada. (unpublished manuscript).

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1983). Chilcotin Flattening. Canadian Journal of Linguistics, 28 (2), 123-132.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1986). Ambisyllabicity and Nasalization in Chilcotin. In Working Papers for the 21st International Conference on Salish and Neighboring Languages (Pp. 1–6). Seattle: University Of Washington.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1989). Articulatory and Acoustic Correlates of Pharyngealization: Evidence from Athapaskan. In D. Gerdts & K. Michelson (Eds.), Theoretical Perspectives on Native American Languages (Pp. 133–145). Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1989). Chilcotin Tone and Verb Paradigms. In E.-D. Cook & K. Rice (Eds.), Athapaskan Linguistics (Pp. 145–198). Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1993). Chilcotin Flattening and Autosegmental Phonology. Lingua, 91 12/3, 149-174.

- Cook, Eung-Do; & Rice, Keren (Eds.). (1989). Athapaskan Linguistics: Current Perspectives on a Language Family. Trends in Linguistics, State of-the-art Reports (No. 15). Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. ISBN 0-89925-282-6.

- Gafos, Adamantios. (1999). The Articulatory Basis of Locality in Phonology. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-8153-3286-6. (revised version of the author's Doctoral dissertation, Johns Hopkins University).

- Hansson, Gunnar O. (2000). Chilcotin Vowel Flattening and Sibilant Harmony: Diachronic Cues to a Synchronic Puzzle. (Paper presented at the Athabaskan Language Conference, Moricetown, British Columbia, June 10).

- Krauss, Michael E. (1975). Chilcotin Phonology, a Descriptive and Historical Report, with Recommendations for a Chilcotin Orthography. Alaskan Native Language Center. (unpublished manuscript).

- Krauss, Michael E., and Victor K. Golla (1981) Northern Athapaskan Languages, In June Helm (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Subarctic, Vol. 6. Smithsonian Institution, Washington.

- Latimer, R. M. (1978). A Study of Chilcotin Phonology. (M.A. thesis, University of Calgary).

- Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23228-7 (hbk); ISBN 0-521-29875-X.