Ignaz Trebitsch-Lincoln

Ignatius Timothy Trebitsch-Lincoln (Hungarian: Trebitsch-Lincoln Ignác, German: Ignaz Thimoteus Trebitzsch; 4 April 1879 – 6 October 1943) was a Hungarian-born adventurer and convicted con artist. Of Jewish descent, he spent parts of his life as a Protestant missionary, Anglican priest, British Member of Parliament for Darlington, German right-wing politician and spy, Nazi collaborator, Buddhist abbot in China, and self-proclaimed Dalai Lama.

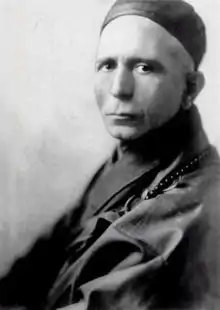

Ignatius Timothy Trebitsch-Lincoln | |

|---|---|

Trebitsch-Lincoln as Chao Kung | |

| Born | 4 April 1879 |

| Died | 6 October 1943 (aged 64)[1] |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Occupation(s) | Adventurer, con artist |

Early clerical career

Ignácz Trebitsch (Hungarian: Trebitsch Ignác(z)) was born to an Orthodox Jewish family in the town of Paks in Hungary in 1879, subsequently moving with his family to Budapest. His father, Náthán Trebitsch (Hungarian: Trebitsch Náthán), was from Moravia.

After leaving school he enrolled in the Royal Hungarian Academy of Dramatic Art,[1] but was frequently in trouble with the police over acts of petty theft. In 1897 he fled abroad, ending up in London, where he took up with some Christian missionaries and converted from Judaism. He was baptised on Christmas Day 1899, and set off to study at a Lutheran seminary in Breklum in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, destined for the ministry. Restless, he was sent to Canada to carry out missionary work among the Jews of Montreal, first on behalf of the Presbyterians, and then the Anglicans. He returned to England in 1903 after a quarrel over the size of his stipend.

He became Tribich Lincoln (or I. T. T. Lincoln) by deed poll in October 1904[1] and secured British naturalisation on 11 May 1909.[2]

Member of Parliament

Trebitsch-Lincoln had the ability to talk himself into virtually any situation, and into any company. He made the acquaintance of the Archbishop of Canterbury, who appointed him as a curate in Appledore, Kent, his last ecclesiastical post. Soon thereafter he met Seebohm Rowntree, the chocolate millionaire and prominent member of the Liberal Party, who offered him the position of his private secretary. With Rowntree's support, he was nominated in 1909 as the prospective Liberal candidate for the Parliamentary constituency of Darlington in County Durham, even though he was still a Hungarian citizen at the time. In the election of January 1910 he beat the sitting Unionist,[3] whose family had held the seat for decades. However, at the time of this dramatic entrance to political life, MPs were not paid and Lincoln's financial troubles grew worse. He was unable to stand when a second general election was called in November 1910. Darlington returned to its old allegiance.

International confidence man

In the years leading up to the outbreak of the First World War he was involved in a variety of failed commercial endeavours, living for a time in Bucharest, hoping to make money in the oil industry. Back in London with no money, he offered his services to the British government as a spy. When he was rejected he went to the Netherlands and made contact with the Germans, who employed him as a double agent.

Returning to England, he narrowly escaped arrest, leaving for the United States in 1915, where he made contact with the German military attaché, Franz von Papen. Papen was instructed by Berlin to have nothing to do with him, whereupon Trebitsch sold his story to the New York World Magazine, which published under the banner headline Revelation of I. T. T. Lincoln, Former Member of Parliament Who Became a Spy. His book Revelations of an International Spy was published by Robert M. McBride in New York in 1916.[4]

The British government, anxious to avoid any embarrassment, employed the Pinkerton agency to track down the renegade. He was returned to England – not on a charge of espionage, which was not covered by the Anglo-American extradition treaty, but of fraud, far more apt in the circumstances. He served three years in Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight and was released and deported in 1919. His British nationality was revoked by the Home Secretary on 3 December 1918.[5]

Germany and Austria

A penniless refugee, Trebitsch-Lincoln worked his way bit by bit into the extreme right-wing and militarist fringe in Weimar Germany, making the acquaintance of Wolfgang Kapp and Erich Ludendorff among others. In 1920, following the Kapp Putsch, he was appointed press censor to Kapp's provisional government. In this capacity he met Adolf Hitler, who flew in from Munich the day before the Putsch collapsed.[6]

With the fall of Kapp, Trebitsch fled south from Munich to Vienna to Budapest, intriguing all along the way, linking up with a whole variety of fringe political factions, such as a loose alliance of monarchists and reactionaries from all over Europe known as the White International. Entrusted with the organization's archives, he promptly sold the information to the secret services of various governments. Tried and acquitted on a charge of high treason in Austria, he was deported yet again. His name was also used by other impostors: following the assassination of the Italian MP Giacomo Matteotti, in 1924 the police arrested a certain Otto Thierschadl alias Chirzel, who gave as his name Tribisch Lincoln.[7]

Conversion to Buddhism

He ended up in China, where he took up employment under three different warlords including Wu Peifu. Supposedly after a mystic experience in the late 1920s, Trebitsch converted to Buddhism, becoming a monk. In 1931 he rose to the rank of abbot, establishing his own monastery in Shanghai. All initiates were required to hand over their possessions to Abbot Chao Kung (Chinese: 照空; pinyin: Zhào Kōng), as he now called himself. He also spent time seducing nuns.

In 1937 he transferred his loyalties yet again, this time to the Empire of Japan, producing anti-British propaganda on their behalf. Chinese sources say that he also wrote numerous letters and articles for the European press condemning Japanese imperial aggression in China. After the outbreak of the Second World War, he also made contact with the Nazis, offering to broadcast for them and to raise up all the Buddhists of the East against any remaining British influence in the area. The chief of the Gestapo in the Far East, SS Colonel Josef Meisinger, urged that this scheme receive serious attention. It was even seriously suggested that Trebitsch be allowed to accompany German agents to Tibet to implement the scheme. He proclaimed himself the new Dalai Lama after the death of the 13th Dalai Lama, a move that was supported by the Japanese but rejected by the Tibetans.[8]

Heinrich Himmler was enthusiastic, as was Rudolf Hess, but it all came to nothing after the latter flew to Scotland in May 1941. After this, Adolf Hitler put an end to all such pseudo-mystical schemes. Even so, Trebitsch may have continued his work for the German and Japanese security services in Shanghai until his death in 1943.

Death

In response to a letter protesting the Holocaust which Trebitsch-Lincoln had written to Hitler, the Nazi High command requested that the Japanese occupation government in Shanghai poison Trebitsch-Lincoln in 1943. The response to this request is not known; however, Trebitsch-Lincoln did die of stomach trouble in Shanghai in 1943, aged 64. Yosef Nedava, who attended his funeral, assumed that the coffin was empty. Years later he wrote Trebitsch's biography in Hebrew (1956).

See also

References

- "Lincoln, Ignatius Timotheus Trebitsch". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/51599. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "No. 28256". The London Gazette. 1 June 1909. p. 4176.

- "No. 28338". The London Gazette. 11 February 1910. p. 1029.

- I. T. T. Lincoln, Revelations of an International Spy. New York, Robert M. McBride & Company, 1916.

- "No. 31065". The London Gazette. 13 December 1918. p. 14705.

- Wasserstein, Bernard (8 May 1988). "On The Trail of Trebitsch Lincoln, Triple Agent". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- Paul Chautard, DRAMES DE L'ESPIONNAGE. Les héros mystérieux, Paris-soir (Paris), 26 mars 1934, p. 3.

- Orlov-Astrebski, Ivan (7 April 1945). "Buddha Threatens the Japanese". Sydney Morning Herald. p. 9. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

Further reading

- Wasserstein, Bernard (1988). The Secret Lives of Trebitsch Lincoln. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04076-8.

- "On the Trail of Trebitsch Lincoln, triple agent". New York Times. 8 May 1988. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- John Gross (17 May 1988). "Books of The Times; On Clear Duplicity and Doubtful Consequence". New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2008. by John Gross, 17 May 1988

- Ju-Zan 巨赞, "Yang heshang Zhao-Kong," 洋和尚照空 in Wenshi ziliao xuanji 文史资料选辑, No. 79, ed. Quanguo Zhengxie wenshi ziliao weiyuanhui 全国政协文史资料研究委员会, 1982, pp. 165–177.

- The Self-made Villain: A biography of I.T.Trebitsch Lincoln, By David Lampe & Laszlo Szenasi, Hardcover: 215 pages, Publisher: Cassell (1961), Language: English, ASIN: B0000CL8HL