Treasure of El Carambolo

The Treasure of El Carambolo (Spanish: Tesoro del Carambolo) was found in El Carambolo hill in the municipality of Camas (Province of Seville, Andalusia, Spain), 3 kilometers west of Seville, on 30 September 1958.[1] The discovery of the treasure hoard spurred interest in the Tartessos culture,[1] which prospered from the 9th to the 6th centuries BCE,[2] but recent scholars have debated whether the treasure was a product of local culture or of the Phoenicians.[3] The treasure was found by Spanish construction workers during renovations being made at a pigeon shooting society.[4][5]

After years of displaying a replica while the original treasure was locked in a safe, the Archeological Museum of Seville has put the original artifacts on permanent display since January 2012.[6] A replica is on display in the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid.

Gold treasure

.jpg.webp)

It consists of 21 pieces of crafted gold: a necklace with pendants, two bracelets, two ox-hide-shaped pectorals, and 16 plaques.[7] The jewelry had been buried inside a ceramic vessel. The plaques may have made up a necklace or diadem;[8] alternatively, some current thinking is that they were attached to textiles adorning animals led to sacrifice, while the necklace and bracelets were worn by the priest officiating.[9] Following the discovery, archaeologist Juan de Mata Carriazo excavated the site. The treasure has been dated to the 8th century BCE, with the exception of the necklace, which is thought to be from 6th century BCE Cyprus. The hoard itself is thought to have been deliberately buried in the 6th century BCE.[5]

Two distinct archaeological sites have been found at El Carambolo with the later replacing the first. One, on top of a hill, referred to as "Carambolo Alto" dates from the ninth to mid-eighth century BCE. Remains at this site consist mainly of burned huts and pottery with geometric designs. The first site reflects indigenous culture and is dated before the arrival of the Phoenicians. The second site, on the side of the hill facing the river, is known as "Carambolo Bajo." This site dates from the beginning of trade with the Phoenicians in the mid-eighth century. The Treasure of El Carambolo is associated with the second site, and may have been buried at the time of the site's destruction in the sixth century.[10] The discovery of a statue of the Phoenician goddess Astarte cast doubt on the interpretation of the site as an indigenous settlement and led some to argue that it was more Phoenician than Tartessian.[11] Further excavations at the site revealed a Phoenician religious sanctuary.[12]

Phoenician statuette

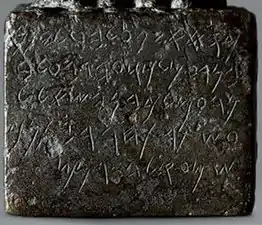

Between 1960 and 1962, a small bronze statuette of Astarte was found in El Carambolo. The plinth (4.1 x 2.8 cm) contained a notable Phoenician inscription, known today as KAI 294, with five lines of Phoenician text. It was delivered to the Archeological Museum of Seville by Joaquín Romero Murube in 1963.[13][14]

Provenance

A 2018 study used chemical and isotopic analysis to try and resolve this debate over the hoard's provenance. The study concluded that while the jewelry was crafted using predominantly Phoenician techniques, the gold itself was sourced from mines only 20 kilometres (12 mi) away, likely the same mines which provided gold for the massive underground tombs at Valencina de la Concepcion.[5][15]

Notes

- Chamorro, 197.

- "Sorry, Atlantis Believers! Scientists Say a Legendary Golden Hoard Did Not Originate from the Underwater City | artnet News". artnet News. 2018-04-12. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- Perea and Hunt-Ortiz.

- Perea and Armbuster, 122.

- "Origin of Mysterious 2,700-Year-Old Gold Treasure Revealed". 2018-04-10. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- Gómez.

- Chamorro, 220-221.

- Chamorro, 220.

- As described and illustrated at the National Archaeological Museum (Madrid) display of their replicas.

- Deamos, 201.

- Deamos, 202.

- Flores and Azogue.

- Solá-Solé, J. M. “NUEVA INSCRIPCIÓN FENICIA DE ESPAÑA (Hispania 14).” Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, vol. 41, no. 2, 1966, pp. 97–108. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41880120 Se trata de un texto de cinco líneas, grabado en el zócalo o peana de una figura de bronce, que representa auna mujer desnuda y sedente de tipo egiptizante. La estatuita, a la que le falta el brazo izquierdo, es de pequeñas proporciones, ya que mide sólo unos 16,5 cm. de altura. El rectángulo anterior del zócalo portador de la inscripción mide aproximadamente unos 4,1 cm. por 2,80 cm. Nuestra estatuita procedería del Cerro de El Carambolo, en Sevilla, en donde habría sido hallada hacia 1960 o 1962. [Footnote: La estatuita parece ser que se descubrió, casualmente, en el Cerro de El Carambolo, de Sevilla, hacia 1960 o 1962 (hay misterio en torno a su hallazgo). 2. Fue entregada al Museo Arqueológico de Sevilla por el limo. Sr. D. Joaquín Romero Murube, Delegado de Defensa del Patrimonio Artístico de Sevilla, el 20 de Octubre de 1963 (registro de entrada en el Museo no. 11.136)]

- Frank Moore Cross, The Old Phoenician Inscription from Spain Dedicated to Hurrian Astarte [1971], in Leaves from an Epigrapher's Notebook: Collected Papers in Hebrew and West Semitic Palaeography and Epigraphy (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2003), p. 273: " bronze statuette...portrays a naked goddess with a modified Ḥatḥor hair style. She is seated, her feet resting on a pedestal which is inscribed with five lines of old Phoenician writing. The writing surface...unhappily is marred by bronze disease, that is, by corrosion which swells and flakes. The figurine with its inscription was published by J. M. Sola-Sola in 1966 in an excellent paper which dated the inscription (and the statuette) in the first half of the eighth century BCE...and went far in deciphering the difficult text"

- Nocete, F.; Sáez, R.; Navarro, A.D.; San Martin, C.; Gil-Ibarguchi, J.I. (2018). "The gold of the Carambolo Treasure: New data on its origin by elemental (LA-ICP-MS) and lead isotope (MC-ICP-MS) analysis". Journal of Archaeological Science. 92: 87–102. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.02.011.

References

- Chamorro, Javier G. (April 1987). "Survey of Archaeological Research on Tartessos". American Journal of Archaeology. 91 (2): 197–232. doi:10.2307/505217. JSTOR 505217.

- Deamos, María Belen (2009). "Phoenicians in Tartessos". In Dietler, Michael; López-Rui, Carolina (eds.). Colonial Encounters in Ancient Iberia: Phoenician, Greek, and Indigenous Relations. ISBN 978-0226148472.

- Fernández Flores, Álvaro; Rodríguez Azogue, Araceli (2005). "El Complejo Monumental del Carambolo Alto Camas (Sevilla). Un santuario Orientalizante en la Paleodesembocadura del Guadalquivir" [The monumental complex of Carambolo Alto, Camas (Seville). An Orientalizing Sanctuary in the paleodesembocadura of the Guadalquivir]. Trabajos de Prehistoria (in Spanish). 62 (1): 111–138. doi:10.3989/tp.2005.v62.i1.58.

- Perea, Alicia; Armbruster, Barbara (1998). "Cambio tecnológico y contacto entre Atlántico y Mediterráneo: el depósito de 'El Carambolo', Sevilla" [Technological change and contact between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean: the deposit of 'El Carambolo', Seville]. Trabajos de Prehistoria (in Spanish). 55 (1): 121–138. doi:10.3989/tp.1998.v55.i1.320.

- Gómez, Reyes (17 January 2012). "El Carambolo se exhibe 54 años después en una sala permanente del Arqueológico". El Mundo (in Spanish).

- Perea, Alicia; Hunt-Ortiz, Mark A. (2009). "New finds from an old treasure: the archaeometric study of new gold objects from the Phoenician sanctuary of El Carambolo (Camas, Seville, Spain)". ArchéoSciences. 2 (33): 159–163. doi:10.4000/archeosciences.2151.

External links

Media related to Treasure of El Carambolo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Treasure of El Carambolo at Wikimedia Commons- Archaeological Museum of Seville - item description