Torsion constant

The torsion constant is a geometrical property of a bar's cross-section which is involved in the relationship between angle of twist and applied torque along the axis of the bar, for a homogeneous linear-elastic bar. The torsion constant, together with material properties and length, describes a bar's torsional stiffness. The SI unit for torsion constant is m4.

History

In 1820, the French engineer A. Duleau derived analytically that the torsion constant of a beam is identical to the second moment of area normal to the section Jzz, which has an exact analytic equation, by assuming that a plane section before twisting remains planar after twisting, and a diameter remains a straight line. Unfortunately, that assumption is correct only in beams with circular cross-sections, and is incorrect for any other shape where warping takes place.[1]

For non-circular cross-sections, there are no exact analytical equations for finding the torsion constant. However, approximate solutions have been found for many shapes. Non-circular cross-sections always have warping deformations that require numerical methods to allow for the exact calculation of the torsion constant.[2]

The torsional stiffness of beams with non-circular cross sections is significantly increased if the warping of the end sections is restrained by, for example, stiff end blocks.[3]

Partial Derivation

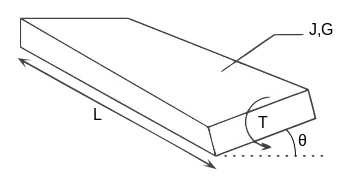

For a beam of uniform cross-section along its length:

where

- is the angle of twist in radians

- T is the applied torque

- L is the beam length

- G is the Modulus of rigidity (shear modulus) of the material

- J is the torsional constant

Torsional Rigidity (GJ) and Stiffness (GJ/L)

Inverting the previous relation, we can define two quantities: the torsional rigidity,

- with SI units N⋅m2/rad

And the torsional stiffness,

- with SI units N⋅m/rad

Examples for specific uniform cross-sectional shapes

Circle

where

- r is the radius

This is identical to the second moment of area Jzz and is exact.

alternatively write: [4] where

- D is the Diameter

Rectangle

where

- a is the length of the long side

- b is the length of the short side

- is found from the following table:

| a/b | |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.141 |

| 1.5 | 0.196 |

| 2.0 | 0.229 |

| 2.5 | 0.249 |

| 3.0 | 0.263 |

| 4.0 | 0.281 |

| 5.0 | 0.291 |

| 6.0 | 0.299 |

| 10.0 | 0.312 |

| 0.333 |

Alternatively the following equation can be used with an error of not greater than 4%:

where

- a is half the length of the long side

- b is half the length of the short side

Thin walled open tube of uniform thickness

- [8]

- t is the wall thickness

- U is the length of the median boundary (perimeter of median cross section

Circular thin walled open tube of uniform thickness

This is a tube with a slit cut longitudinally through its wall. Using the formula above:

- [9]

- t is the wall thickness

- r is the mean radius

References

- Archie Higdon et al. "Mechanics of Materials, 4th edition".

- Advanced structural mechanics, 2nd Edition, David Johnson

- The Influence and Modelling of Warping Restraint on Beams

- "Area Moment of Inertia." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/AreaMomentofInertia.html

- Roark's Formulas for stress & Strain, 7th Edition, Warren C. Young & Richard G. Budynas

- Continuum Mechanics, Fridtjov Irjens, Springer 2008, p238, ISBN 978-3-540-74297-5

- Advanced Strength and Applied Elasticity, Ugural & Fenster, Elsevier, ISBN 0-444-00160-3

- Advanced Mechanics of Materials, Boresi, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-55157-0

- Roark's Formulas for stress & Strain, 6th Edition, Warren C. Young