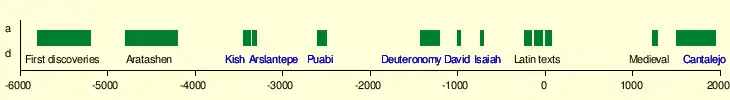

Threshing board

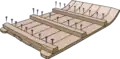

A threshing board, also known as threshing sledge,[1] is an obsolete agricultural implement used to separate cereals from their straw; that is, to thresh. It is a thick board, made with a variety of slats, with a shape between rectangular and trapezoidal, with the frontal part somewhat narrower and curved upward (like a sled or sledge) and whose bottom is covered with lithic flakes or razor-like metal blades.

One form, once common by the Mediterranean Sea, was "about three to four feet wide and six feet deep (these dimensions often vary, however), consisting of two or three wooden planks assembled to one another, of more than four inches wide, in which is several hard and cutting flints crammed into the bottom part pull along over the grains. In the rear part there is a large ring nailed, that is used to tie the rope that pulls it and to which two horses are usually harnessed; and a person, sitting on the threshing board, drives it in circles over the cereal that is spread on the threshing floor. Should the person need more weight, he need only put some big stones over it."[2]

The dimensions of threshing boards varied. In Spain, they could be up to approximately two metres in length and a metre and a half wide. There were also smaller threshing boards, as little about a metre-and-a-half long and a metre wide.[note 1] The thickness of the slats of the threshing board is some five or six cm. Nonetheless, since threshing boards are nowadays custom made, made to order or made smaller as an adornment or souvenir, they may range from miniatures up to the sizes previously described.[note 2]

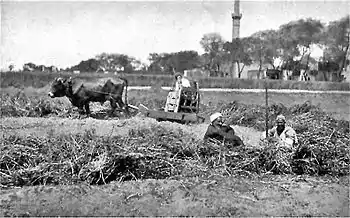

The threshing board has been traditionally pulled by mules or by oxen over the grains spread on the threshing floor. As it was moved in circles over the harvest that was spread, the stone chips or blades cut the straw and the ear of wheat (which remained between the threshing board and the pebbles on the ground), thus separating the seed without damaging it. The threshed grain was then gathered and set to be cleaned by some means of winnowing.

Traditional threshing systems

Until the arrival of combine harvesters, which reap, thresh and clean grain in a single process, the traditional methods of threshing cereals and some legumes were those described by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, with three variants: "The cereals are threshed in some places with the threshing board on the threshing floor; in others they are trampled by a train of horses, and in others they are beaten with flails".[3]

In this manner, Pliny refers to the three traditional methods of threshing grain:

- Beating sheafs of grain against a crushing stone or lump of wood.

- Trampling grain spread on the threshing floor; the trampling would be done by a train of mules or oxen

- Threshing with flails, a type of traditional wooden tool with which one strikes the pile of grain until the seed is separated from the chaff.

Threshing with the threshing board

The threshing board is a historical form of threshing that can still be seen in some regions that practice marginal agriculture. It is also somewhat preserved as an occasional folkloric and ceremonial practice, to commemorate traditional local customs.[4]

For threshing with the threshing board, firstly one brings the baled stalks to the threshing floor. Some are stacked, waiting their turn, and others are untied and placed in a circle forming a pile of grain that is heated by the sun. Then farmers drag the threshing board over the stalks, first going several times around in circles, and then in figure-eights, and stirring the grain with a wooden pitchfork. Sometimes, this work was done with another kind of threshing implement: a Plostellum punicum (Latin; literally "Punic cart") or threshing cart, fitted with a group of rollers, each with metallic transverse razors. In this first stage, the straw is detached from the ear; much chaff and dirty dust remains, mixed with the edible grain. Every time the work of dragging the threshing board is repeated, the grain is stirred again, moving more straw to the edge of the threshing floor. If too much grain is spread on the ground, it has to be raked and swept in order to make a round mound and, if possible, to remove as much straw as possible.

After turning the grain and straw upside down and leaving it to dry during a meal break, farmers carry out a second round of threshing in order to separate the last of the grain from the straw. Then, they use pitchforks, rakes and brooms to create a mound. A pair of oxen or mules pulls the threshing board by means of a chain or a strap fixed to a hook nailed in the front plank; donkeys are not used, because unlike mules and oxen they often defecate on the crops. The driver rides on the threshing board, both guiding the draft animals and increasing the weight of the threshing board. If the driver's weight is not enough, large stones are put on the board. In recent times, the animals are sometimes replaced with a tractor; because the driver no longer sits on the board, the weight of stones becomes more important. Children enjoy riding on the threshing board for fun, and the farmers allow it because their weight is useful, as long as the children are not too boisterous.[5] During this process, if the stalks are excessively squashed, two large metal arcs are affixed to the back of the threshing board; these turn-up and give volume to the straws, behind the threshing.

After threshing is finished, to avoid mixing the dirty remnants with the clean, new stalks, the threshing floor must be cleaned first with a rake to move the heavier material, and then with several brooms (in the narrow sense: they are typically made from "broom shrub"—Cytisus scoparius—and are stronger than domestic brooms[note 3]). Also the straw was accumulated carefully and stored, because it was a good fodder for livestock. The entire process of threshing generates a thin dust that soaks in through the respiratory system and sticks to the throat.

During the sweeping, the husks and the chaff are separated to one part of the threshing-floor, while the grain, still not entirely clean, was winnowed, either by traditional of winnowing with sieves, or by a mechanical winnowing machine.[note 4]

Traditional threshing implements (including the threshing board) were gradually abandoned and replaced by modern combine harvesters. This change, of course, occurred in some areas before others. For instance, in Spain, it happened in the 1950s and 1960s.[6] Until that time, threshing boards were made in certain particular towns and villages with specialised craftsmen. Whereas the woodworking involved is simple, even rough, the flintknapping and the inlaying of flakes into the bottom of board need specialised skills that were passed from father to son. The most famous Spanish town for this work was, doubtlessly, Cantalejo (Segovia), where the craftsmen who made threshing boards were known as briqueros.

History

Origins in the Neolithic and Copper Age

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

Patricia C. Anderson (of Centre d’Etudes Préhistoire, Antiquité et Moyen Age del CNRS), discovered archaeological remains that demonstrate the existence of threshing boards at least 8,000 years old in the Near East and Balkans. The artefacts are lithic flakes and, above all obsidian or flint blades, recognizable through the type of microscopic wear that it has. Her work was completed by Jacques Chabot (of the Centre interuniversitaire d'études sur les lettres, les arts et les traditions, CELAT), who has studied Mitanni (northern Mesopotamia and Armenia). Both count among their specialties the study of microwear analysis, through which it is possible to take a particular piece of flint or obsidian (to take the most common examples) and determine the tasks for which it was used.[7] Concretely, the cutting of cereals leaves a very characteristic glossy pattern of wear, owing to the presence of microscopic mineral particles (phytoliths) in the stalks of the plants. Therefore, scholars using controlled experimental replication studies and functional analysis with a scanning electron microscope are able to identify stone artefacts that were used as sickles or the teeth of threshing boards. The edge damage on the pieces used in threshing boards is distinct because, besides the glossy abrasion characteristic of cutting cereals, they have micro-scars from chipping, as a result of the blows of the threshing board against the rock surface of the threshing floor.[8]

The most productive archaeological site is Aratashen, Armenia: a village occupied between 5000 and 3000 BC (Neolithic and Copper Age). The archaeological excavations have provided thousands of pieces from the knapping of obsidian (suggesting that Aratashen was a centre of production and trade of artefacts of that highly regarded stone); the rest of the archaeological record consists mainly of fragments of common pottery, ground stones, and other agricultural tools. Analysing a sample of 200 lithic flakes and blades, selected from the best-preserved pieces, it is possible to differentiate between those used in sickles and those used in threshing boards. The lithic blades of obsidian were knapped using highly developed and standardized methods, such as the use of a "pectoral crutch" with a copper point.[9] Beginning at the headwaters of the river Euphrates, where this site is located, the craftsmen and peddlers sold their wares throughout the Middle East.

The threshing boards must have been important in the protohistory of Mesopotamia, since they already appear in some of the oldest written documents discovered: specifically, several sandstone tablets from the early town of Kish (Iraq), engraved with cuneiform pictograms, which could be the world's oldest surviving written record, dating to the middle of the 4th millennium BC (Early Uruk period).[10] One of these tablets, preserved in the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford University, appears to have pictures of threshing boards on both faces, next to some numeric symbols and other pictograms. These presumed threshing boards (which might instead be sledges[note 5]) have a shape similar to threshing carts that were used until recently in parts of the Middle East where non-industrial agriculture survived. Descriptions also appear in numerous cuneiform clay tablets as early as the third millennium BC.

There are another representation, in this case without writing, in central Turkey. It is an impression of a cylinder seal from the archaeological site of Arslantepe-Malatya, which appeared near of the named «Temple B». The archaeological layers were dated to 3374 BC using dendrochronology.[11] The stamp shows a figure seated on a threshing board, with a clear image of the lithic flakes inlaid in the bottom of the board. The main figure is sitting (possibly on a throne) under a dossal. In front is a driver or oxherd, and there are peasants with pitchforks nearby. According to M. A. Frangipane, that the seal may illustrate a religious scene:

«This seal [...] (is) interpreted as a ritual threshing scene, emphasising the ideological reference by the Arslantepe elites to images of power expressed in a Mesopotamian environment»[12]

It closely resembles another scene, painted on the walls of the same site (a ceremonial procession of a person of high rank, painted in an archaic lineal style in the colours red and black), although the current condition of the wall obscures the exact nature of the vehicle in which he is seated, it is indeed possible to see that it is pulled by a pair of oxen. Professor Sherratt interprets both scenes as presenting manifestations of civil or religious power.[13] In that era, the threshing board was a sophisticated and expensive implement, built by specialized artisans, using pieces of flint or obsidian; in the case of Lower Mesopotamia, these were imported from far away: in the alluvial plateau of Sumer, as in all south of Mesopotamia, it was impossible to find stone, not even a pebble.[14]

The discovery of a ceremonial sledge (perhaps a threshing board) with gold ornaments in the Tomb of Pu-Abi, one of the "royal tombs" of Ur, dated from the 3rd millennium BC,[15] makes clear the underlying problem of distinguishing in the ancient representations between a true threshing board and a sledge (that is, an unwheeled vehicle for hauling freight). Although we know that the threshing board appears no later than the 4th millennium BC (as we can see in Atarashen and Arslantepe-Malatya), and we also know that the wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in the middle of that same millennium, still, the utilisation and spread of the wheel was not instantaneous. The sledges survived at least until the invention of the articulated axle, nearly 2000 BC. During this time, some vehicles were hybrids: sledges with wheels that could be dismantled to overcome obstacles by carrying it on shoulders or, simply, dragging it.[16] Consequently—except in the case of Arslantepe, where the lithic flakes are clear visible—we cannot determine whether these representations are threshing boards or sledges for freight or for rites.

James Frazer compiled numerous ceremonies of harvest and thresh, that centered on a Cereal Spirit. From the Ancient Egyptian era to pre-industrial period, this spirit seems to have reside d in the first threshed sheaf or, sometimes, in the last one.[17]

Classical Greece and Rome

During the early history of Greece and Rome the threshing board was not used. Only after the development of commerce (with occurred in the 5th and 4th centuries in Greece and 2nd and 1st centuries in Rome) and the subsequent transmission of information from the near east that it became widely used. According to V.V. Struve, who cites, in part, verses of The Iliad, the Greeks of the 8th century BC threshed cereals by trampling them with oxen:[18]

[A]s one who yokes broad-browed oxen that they may tread barley in a threshing-floor - and it is soon bruised small under the feet of the lowing cattle - even so did the horses of Achilles trample on the shields and bodies of the slain.

(Chapter XX of Iliad)

Carthage, which colonized the southeastern Iberian Peninsula in the 3rd century BC, had advanced agricultural technology, greatly superior to the Roman techniques of the time. Their methods astonished travellers such as Agathocles and Regulus, and were an inspiration for the writings of Varro and Pliny. One well-known Carthaginian agronomist, Mago, wrote a treatise that was translated into Latin by order of the Roman Senate. The ancient Romans describe Tunisia, today mainly desert, as a fertile landscape of olive groves and wheat fields. In Hispania, the Carthaginians are known to have introduced several new crops (mainly fruit trees) and some machines like the threshing board, either the version with stone-chips (tribulum in Latin) or the version with rollers (threshing cart, named in their honour plostellum punicum by the Romans).[19]

In Rome, the threshing board had only economic significance, without the religious symbolism it took on in the Hebrew Bible. The treatises of agriculture written by Roman experts as Cato, Varro, Columella and Pliny the Elder (quoted above), touch the topic of threshing. In chronological order:

- Cato: In the time of Cato the Elder—that is, the 2nd century BC—Rome was intensely connected with the conquered areas of Greece and Carthage, whose higher degree of agricultural development threatened Roman traditionalism. Cato's book De Agricultura[20] was against exotic innovations such as the threshing board in its different variants, defending instead a traditional agricultural system based on manual labour. To some writers, Cato's ideas drove, indirectly, to the disintegration of republican society and even the imperial economy. Cato preferred threshing by trampling by mules or oxen. He doesn't expressly mention the threshing board, in spite of the fact it was already spreading through the empire. It is, then, "almost impossible to define, on the basis of Cato's report, when this or that implement or refinement came into use".[21]

- Varro: Unlike Cato, Marcus Terentius Varro was not a man of action but a scholar, a πολιγραφοτάτω, in the 1st century BC. Varro, whose studies were wider than Cato's, tried to combine the cosmopolitan Greek outlook with Rome's provincial traditions. In his book of agricultural advice Rerum Rusticarum de Agri Cultura[22] Varro only twice reflects the reality of his times by mentioning threshing boards. He advises, "None of the implements that can be produced in the plantation (farm) itself should be bought, as with almost all everything which is made from unfinished wood such as hampers, baskets, threshing boards, stakes, rakes…";[23] the inclination to self-sufficiency that he demonstrates here would later be harmful to Rome. Varro nonetheless shows himself more open to innovation that Cato: "To achieve an abundant and high-quality harvest, the stalks should be taken to the threshing floor without piling them up, so the grain is in the best condition, and the grain (should be) separated from the stalks on the threshing floor, a process which is done, among other ways, with a pair of mules and a threshing board. This is made with a wooden board (with its underside) equipped with stone-chips or saws of iron, which, with a plow in front or a large counterweight, is pulled by a pair of mules yoked together and thus separates the grain from the stalks…".[24] That is, he explains in a very didactic way how the threshing boards works and the advantages of this innovative device. Next, he talks about the variant called plostellum poenicum (=punicum=Punic=Carthaginian), a threshing implement with rollers and metallic saws whose origin is, as we have already seen, Carthaginian, and which was used in Hispania (which had, in the past, been controlled by Carthage): "Another way to make it is by means of a cart with teethed rollers and bearings; this cart is named plostellum punicum, in which one can sit and move the device that is pulled by mules, as it is done in Hispania Citerior and other places."[25]

- Columella (Lucius Junius Moderatus, beginning of Common Era - 60s): a native of Hispania Baetica; after finishing his military career, Columella worked managing large estates. This writer from Hispania brings a new note to this topic, writing, in this case, about threshing floors: "The threshing floor, if it is possible, must be placed in such way that it can be overseen by the master or by the foreman; the best is one that is cobbled, because not only allows that the cereal be quickly threshed, since the ground don't give way to the blows of hoofs and threshing boards, but also, these cereals, before being winnowed, are cleaner and lack the pebbles and little clods that always remaine in a threshing floor of pressed earth."[26]

- Pliny: Pliny the Elder (23 - 79) only compiles what his predecessors had written, which we have already quoted.[27]

Middle Ages

In Western Europe, the barbarian invasions of Europe had detrimental effects upon agriculture, leading to the loss of many of the more advanced techniques, among them the threshing board, which was completely alien to Germanic tradition. The eastern Mediterranean areas, on the other hand, continued the use of the threshing board, passing into the Muslim culture, where it took deep root.

In the Iberian Peninsula, in the Visigothic kingdom and the Christian zone during the Reconquista, the threshing board was little known (although awareness of it never quite disappeared[note 6]). The degradation extended not only to the economy, but also to the very sources that we have to study the period: scholars are confronted with a documentary void that is difficult to get around. It is certain that in Islamic Al-Andalus, the threshing board continued to be very popular, which led to the Christians recuperating the tradition as they advanced in the Reconquista. This act coincides with a generalized recovery in all of Europe. Economic prosperity began to return at the start of the 11th century; the experts speak of the increased area of tilled lands; the increased use of draft animals (first oxen, thanks to the frontal yoke, and later horses, thanks to harness collar); of the increase in metal tools and improved metalworking; of the appearance of the moldboard plough, often with wheels; and the increase in watermills. Livestock became a sign of progress: peasants, less dependent and more prosperous, became able to buy draft animals, and even plows. The peasants who had their own plow and one or two draft animals were a small elite, pampered by the feudal lord, who acquired a distinct status, that of yeoman farmers, quite distinct from farm-hand labourer whose only tool was their own arms.[28] The existence of draft animals does not imply the diffusion of the threshing board in Western Europe, where the flail continued to be the preferred threshing implement.[note 7] On the other hand, in Spain, the weight of Eastern tradition made the difference: Professor Julio Caro Baroja admits that in Spain the threshing board appears cited or represented in works of art. Concretely, he mentions some Romanesque reliefs in Beleña (Salamanca) and Campisábalos (Guadalajara), both from the 12th century.[29] One may add a document written in 1265, in which a woman named Doña Mayor (widow of one Don Arnal, an ecclesiastical tax collector, and thus a person of good position), leaves to the diocese chapter of Salamanca her inheritance of Valcuevo, a farm in the municipality of Valverdón, Salamanca:

And I, Doña Mayor, leave on my death these two yokings of country state above referred to the Cathedral Chapter, well preserved with 76 bushels of wheat, 38 bushels of rye, and 38 bushels of barley to seed each yoking and with ploughshares, and with plows, and with ploughbeams, and with threshing boards and with all the accoutrements that a well-laid-out property should have.[30]

These documents, at least testify for the presence of threshing boards, which, undoubtedly was continuous from then until recently in the Mediterranean basin. The rest is mere generalized speculation, given that traditional historiography centers on features more like of Western Europe. In any case, none of the consulted authors describe the threshing board as playing a relevant part in the progress of medieval agriculture. We must, then, join with the despair of French historian Georges Duby, in his complaint:

Through all that has been said, we can see how interesting it would be to measure the influence of technical progress on agricultural output. Nevertheless, we must renounce this hope. Before the end of the 12th century, the methods of seignorial administration were all quite primitive; they granted little importance to writing and even less to numbers. The documents are more deceptive than those of the Carolingian era.[31]

Nowadays, numerous elements of traditional agriculture are being lost, and because of this various entities have been working to conserve or recover this cultural capital. Among these is an international interdisciplinary project called E.A.R.T.H., Early Agricultural Remnants and Technical Heritage. Participating countries include Bulgaria, Canada, France, Russia, Scotland, Spain, and the United States. Investigations center on broad archeological, documentary and ethnological aspects, related to diverse elements of traditional agriculture, threshing boards among them, in diverse countries, historical periods and societies.[32]

Craftsmen from Cantalejo

Cantalejo is located at the confluence of the Duraton River and the Cega River. Modern Cantalejo arose in the 11th century, although there are architectural remains that are much older, and forms part of Segovia province in Spain. It was apparently prosperous at the beginning but, lost its liberty in the 17th century and became a jurisdictional lordship. There is no clear record of when the specialized craft of making threshing boards was introduced into Cantalejo, but all who have written on the topic indicate that it was probably during the 16th or 17th century.[33]

The production of threshing boards appears to coincide with the arrival of foreign artisans, although this is speculation based on the fact that the artisans' form of speech (see the section on gacería) includes aspects of many foreign languages, especially French. The makers of threshing boards and plows were called «Briqueros», a word of French origin that refers to the making of tinderboxes and matchlocks for guns, which in France were called briquets, literally in archaic French: «Petite pièce d’acier don't on se sert pour tirer du feu d’un caillou.» (today, synonym of briquette or flammable matter, but also refers to a lighter) for the early firearms (Flintlocks, arquebuses, muskets...). It is therefore plausible that foreign gunsmiths introducing firearms in the Iberian Peninsula created an important colony in Cantalejo, although it is difficult to determine their origin[note 8]

In any case, with time Cantalejo opted for peaceful and productive crafts such as the making of diverse agricultural implements, including threshing boards. By the 1950s, Cantalejo had reached 400 workshops producing more than 30,000 threshing boards each year; this suggests that more than half the population was dedicated to this occupation. The threshing boards were then distributed throughout the entire Meseta Central of Spain.

This article concentrates on threshing boards made only with flint chips, although there were threshing boards made with metal teeth or according to other, less common designs.[34]

Making the wooden frame

At the end of summer, or in the autumn, work began with the selection of black pines, which they cut and carefully smoothed with a device called a tronzador until the trunks were formed into cylinders nearly two meters in length; these log sections were called tozas. They also prepared long, straight planks to serve as transverse headpieces. They carried the log sections to the sawmill, where they cut slats as wide as the log permitted (no less than 20 centimeters), of some five centimeters in thickness and with a curved shape (just like a ski) on the end that would eventually be in front. The planks were dried in the sun for several months, turned over every so often. The village during this period took on a peculiar appearance, as many buildings had their façades covered with drying planks. Afterwards, these were piled in castillos, crossing some slats with others in order to make the pile more stable.

The pine tozas, from which the slats were cut

The pine tozas, from which the slats were cut Slats aligned, before forming the threshing board

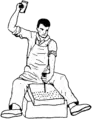

Slats aligned, before forming the threshing board Chiseling the slat

Chiseling the slat

Once the slat was in the right conditions, the next process was chiseling: using a hammer and chisel to prepare the slots (ujeros for the chips of flint (chinas or lithic flakes). The chiseling was done with the slats front-on, guided by pencil-marks so the workman wouldn't err. Before beginning, the workman made sure that the slat had not warped since being cut, as that would make it unusable.

The next pass took place in the mechanical presses; the Spanish language term for these was "cárceles", "jails". The three, four, or five planks had to be perfectly joined: spread with glue and pressed, using small reinforcement jigs, called tasillos (wooden cylinders glued and nailed with a mallet at the edges of a slat), and wedges. When the slats were well-aligned and fixed in place, the cabezales (headers), or crosspieces, were nailed in place with big nails known in Spain as puntas de París (although, at least in the 19th and 20th centuries, they came from Bilbao).

The planks glued, as they are in the cárceles

The planks glued, as they are in the cárceles Placing the "headers" (cabezales) with large iron nails

Placing the "headers" (cabezales) with large iron nails Placing of stopgaps in the junctions.

Placing of stopgaps in the junctions. The wooden structure completed, but with the cutting stones not yet added

The wooden structure completed, but with the cutting stones not yet added

Once the basic structure of the threshing board is ready, it must be smoothed. This is first done by "working" it with an adze lengthwise, along the grain. Then the final finishing is done with various specialized carpenter's planes, on both top and bottom; first going across in a transverse direction, and later lengthwish.

The final phase of the work consisted of covering the junctions of the slats on the top side, which is done with thin strips at the front, tacked on with a board called the "front piece", and on the rest using long thin little boards (tapajuntas or stopgaps). On the front header they attached a strong hook for the barzón, or iron ring with a strap or a long rod for tying on the drafthorses or oxen.

Working the stone flakes

To create the lithic flakes used to cover threshing boards, the briqueros in Cantalejo used a manufacturing technique similar to prehistoric methods of making tools, except that they used metal hammers rather than percussors made of stone, wood, or antler.[35]

The raw materials preferred by these artisans was a whitish flint imported from the province of Guadalajara. When they had to repair threshing boards at home, if they did not have any other raw materials, they would use rounded river pebbles, made of homogeneous, high-grade quartzite, which they selected during their travels. The flint from Guadalajara was extracted from quarries in large blocks, which were split by hand with hammers of various sizes until the stone reached a size small enough to be comfortably held in the hand.

Knapping: Once manageable chunks of flint were obtained, knapping to obtain lithic flakes was performed using a very light hammer (called a pickaxe) with a narrow handle and a pointed head. Knapping was considered "men's work." To work quartzite pebbles, they used a hammer with a head that was rounded and slightly wider. During the process of removing stone flakes, they sometimes resorted to a normal hammer to crack the stone and achieve perussion plains inaccessible with the pickaxe alone.

The briquero held the stone core in the left hand, protected with a piece of leather and with the palm upward, and struck rapid blows using a pick held in the right hand. The stone flakes would fall into the palm of the right hand, on top of the leather protector, which allowed the worker to evaluate them during fractions of a second: if they were acceptable, the briquero allowed them to fall into a tin; if not, he threw them into a reject pile.[note 9] This pile was also where the briquero threw used-up stone cores —that is, stone blocks incapable of producing more chips; pieces of stone broken by accident; cortical flint flakes, useless fragments, and debris.

The working of pebbles was similar to the working of flint, except that with pebbles only the outside layer was chipped off. Thus, the pebbles were essentially "peeled" and discarded (unlike flint stones, whose interiors were worked until they were used up); using only the cortical flakes.

Covering the board with stone flakes was mainly the work of women called enchifleras. The task is monotonous and repetitive. Up to three thousand lithic flakes may be pounded into a large threshing board. In addition, it is necessary to sort the flakes: small ones in the front, medium-sized in the middle, and the largest on the sides and in the back. It is necessary to pound in each flake without damaging its sharp edge, although it was impossible to avoid leaving at least some small mark (a "spontaneous retouch" in technical terms). The tool used was a light hammer with a cylindrical head and flat or concave ends. The flakes are inserted into the cracks at their thickest part (technically, the percussion zone, that is, the proximal heel of the flake as it is struck off.)

Distribution

Threshing boards from Cantalejo captured nearly all the sales in Castile and León, Madrid, Castile-La Mancha, Aragon and Valencia. They sometimes also reached Andalusia and Cantabria.[34] At first, artesans from Cantalejo travelled with large carts loaded with selected threshing boards, winnowing bellows, grain measures (of different traditional dry units: celemín is a wooden case with 4,6 L, cuartilla has 14 L, and fanega equivalent to 55.5 L...) and other implements for threshing or winnowing, which they peddled from town to town. They also carried flint chips, and tools and supplies for repairing damaged threshing boards and farming implements. In later times, they traveled by train to pre-arranged stations, and then in small trucks. They typically brought their entire families along; combined with their strange manner of speaking and unusual occupation, this gave the briqueros an air of mystery. They began selling threshing boards as soon as the threshing boards were complete, beginning in April and lasting until August. The briqueros would then return to their home town (the Vilorio) to celebrate the festivals of the Assumption of Mary (August 15) and Saint Roch (August 16) with their families.

Gacería

Gacería is a cant or argot used by makers and vendors of threshing boards in Cantalejo and some other parts of Spain. It is not a technical vocabulary, but rather a code made up of a small group of words that allows the speakers to communicate freely in the presence of strangers without others understanding the content of the conversation.

Gacería was purely verbal, colloquial, and associated with the selling of threshing boards; as a result, it largely disappeared with the mechanization of agriculture. Nevertheless, a number of studies have attempted to record its varied aspects. There are many doubts regarding the origin of the words that make up the vocabulary of Gacería, including the word Gacería itself, which may derive from the Basque word gazo, which means "ugly" or "good-for-nothing".[36] The most commonly accepted opinion is that most of the words derive from French, with additions from other languages including Latin, Basque, Arabic, German, and even Caló.[34] What is certain is that the makers and vendors of threshing boards took words from any area they visited regularly, creating a linguistic mishmash.

Related threshing implements

In general, the term "threshing board" is used to refer to all the different variants of this primitive implement. Technically, we should distinguish at least the two main types of threshing boards: the "threshing sledge," which is the subject of this article, and the "threshing cart."

The "threshing sledge" is the most common type. As its name indicates, it is dragged over the ripe grain, and it threshes using cutting pieces made of stone or metal. This is what is referred to in Hebrew as morag (מורג) and in Arabic as mowrej. Strictly speaking, the threshing boards of the Middle East have characteristics that render them easily distinguishable from those found in Europe. On the Iberian peninsula, cutting blades found on the bottom part of the threshing board are arranged on end and in rows roughly parallel to the direction of threshing. In contrast, the mogag and mowrej found to the Middle East have circular holes (made with a special short, wide drill) into which are pressed small round, semicircular stones with sharp ridges. (See a detail photo of a Middle-Eastern threshing board).

|

A second model, which the classic sources refer to as plostellum punicum (literally, the "Punic cart"), ought to be called "threshing cart". Although the Carthaginians, heirs of the Phoenicians, brought this model to the Western Mediterranean, this implement was known at least since the second millennium BC, appearing in the Babylonian texts with a name that we can transliterate as gīš-bad. Both variants continued to be used well into the 20th century in Europe, and continue to be used in the regions where agriculture has not been mechanized and industrialized. Museums and collectors in Spain retain some threshing carts, which were once highly prized in areas such as the province of Zamora, where they were used to thresh garbanzos.

See also

- Stone boat a similar looking sledge but with a smooth bottom

Notes

- The big threshing boards were intended for a "yoke" or pair of draft animals (oxen or mules), whereas the smaller ones were intended to be drawn by a single animal.

- There are specialized original threshing boards for garbanzos, with smaller dimensions than those used for cereal grains; also, at times, instead of stone chips, they have rollers with crammed blades: "threshing carts" («trillo de ruedas») known in antiquity as Plostellum punicum.

- Long ago it was customary among children from the Spanish Meseta) to extract the gummy plant sap for chewing, like chewing-gum. Today, we know that the leaves and stalks of scotch broom contain alkaloids (such as sparteine and isosparteine) that, in large amounts, can be poisonous; but in small quantities, are medicinal or, even, narcotic, altering the cardiac rhythm, which explains the former popularity of this gummy substance among young people.

- The non-industrial agriculture that remains in marginal places of Europe and many underdeveloped Mediterranean areas, and where the threshing board and other traditional implements remain customary, preserve an ancestral vocabulary that forms part of the heritage of these countries. Almost all of this vocabulary is in danger of extinction.

- Sledges were as vehicles for freight before the invention of wheel.

- Isidore of Seville in his Etymologiae (Libro XVII: La agricultura), simply repeats what the classical sources had to say on this theme, indicating his merely slight familiarity with the technology.

- The threshing board, as we have had occasion to repeat throughout this article, was expensive, as were the conditions of its use, only the wealthy laborers and the nobility could afford a threshing board and a plow. Its use was, perhaps, another lordly ban, and thus a mark of a bondage. On the other hand, the flail was a cheap, simple tool, which anyone could get hold of and which supposed a certain independence and freedom.

- There are similar cases in other parts of Europe. For example, in England, "a new industry was born at Brandon, Suffolk nearly 200 years ago when men who may well have been immigrants to the town began the knapping of gunflints whose effectiveness was proved on the field of Waterloo." See that web-site

The writer A. J. Forrest still knew flintknappers fifty years ago and wrote a book about this unusual industry, which flourished in times of war and survived thanks to exports to distant parts of the British Empire; the last documented exports were sent to Cameroon in 1947.Forrest, A. J. (1983). Masters of Flint. Terence Dalton. ISBN 0-86138-016-9.

Something similar may have occurred in Cantalejo, but without the military power of Great Britain or its empire, the Spanish briqueros had to adapt their production to the national market, agriculture. - The activity is rhythmic and very rapid, too fast for an inexperienced observer to determine whether a chip is adequate or not to use in a threshing board -- whether it is too small, or too large, or has the proper shape.

References

Citations

- Columella, De Re Rustica (Book 1, chapter 6:23)

- Boutelou, Claudio (1806). "Sobre un trillo de nueva invención ("About a threshing board of recent invention")". Semanario de Agricultura y Artes (in Spanish). Madrid. XIX: 50 et. seq.

«…de tres a cuatro pies de ancho y unos seis de largo, variando frecuentemente estas dimensiones, y se compone de dos o tres tablones ensamblados unos con otros, de más de cuatro pulgadas de grueso, en los que se hallan embutidas por su parte inferior muchos pedernales muy duros y cortantes que arrastran sobre las mieses. En la parte anterior hay clavada una argolla para atar la cuerda que le arrastra, y a la que se enganchan comúnmente dos caballerías; y sentado un hombre en el trillo lo conduce dando vueltas sobre la parva extendida en la era. Si el hombre necesita más peso, pone encima piedras grandes»

- «Messis ipsa alibi tribulis in area, alibi equarum gressibus exteritur, alibi perticis flagellatur» Gaius Plinius Secundus, Naturalis Historia, Liber XVIII (naturae frugum), lxxii - 298; Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book XVIII (Agriculture), lxxii - 298.

- (in Spanish) La trilla tradicional en Castroviejo, Rioja Alta ("Traditional threshing in Castroviejo, Rioja Alta, Spain").

- Lucas Varela, Antonio (2002). Cerramícalo (in Spanish). Fundación Hernández Puertas de Alaeojs (Valladolid) - Madrid. ISBN 84-607-4578-3.

- Martínez Ruiz, José Ignacio (2005). "La fabricación de maquinaria agrícola en la España de Postguerra" (PDF) (in Spanish). VIII Congreso de la Asociación Española de Historia Económica, Sesión B3, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. p. 6. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- Anderson, Patricia C.; Chabot, Jacques; van Gijn, Annelou (2004). "The Functional Riddle of 'Glossy' Canaanean Blades and the Near Eastern Threshing Sledge". Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology. 17 (1, June): 87–130. doi:10.1558/jmea.17.1.87.56076.

- Benito del Rey, Luis y Benito Álvarez, José-Manuel (1994). "La taille actuelle de la pierre à la manière préhistorique. L'exemple des pierres pour Tribula à Cantalejo (Segovia - Espagne)". Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française (in French). Tome 91 (Numéro 3, mai–juin).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (p. 222 and footnote 10) - (in French) «Grande béquille pectorale»: Pelegrin, Jacques (1988). "Débitage expérimental par pression, "du plus petit au plus grand"". Technologie Préhistorique. Notes et monographies techniques (25): 46. ISBN 2-222-04235-6.

- Clairborne, Robert (1974). The Birth of Writing. Time-Life Inc. p. 10. ISBN 0-8094-1282-9.

- Graphic on the Cornell University web site.

- Frangipane, M. A. (1997). "4th millennium temple palace complex at Arslantepe-Malatya. North-South relations and the formation of early state societies in the northern regions of greater Mesopotamia". Paléorient. 23 (1): 45–73. doi:10.3406/paleo.1997.4644.. p. 64-65

- Sherratt, Andrew (2005). "ArchAtlas, an electronic atlas of archaeology Animal traction and the transformation of Europe". P. Pétrequin. Proceedings of the Frasnois Conference. Sheffield, England (19–21).

- Hamblin, Dora Jane (1973). The First Cities. Time-Life Inc. ISBN 0-8094-1301-9. p.90.

- Wooley, Leonard (1934). Ur Excavations II, The Royal Cemetery. London-Philadelphia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) p.73 et. seq. - Hamblin, Dora Jane (1973). The First Cities. Time-Life Inc. ISBN 0-8094-1301-9.

- Frazer, James George (1995) [1922]. The Golden Bough (reprint). Touchstone edition. ISBN 0-684-82630-5. (p. 488 and followings)

- Struve, V. V. (1979). Historia de la Antigua Grecia (in Spanish) (Third ed.). Madrid: Akal Editor. ISBN 84-7339-190-X. p. 115

- Blázquez, José María (1983). "Capítulo XVI, Colonización cartaginesa en la península Ibérica". Historia de España antigua. Tomo I: Protohistoria (in Spanish) (Second ed.). Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra. ISBN 84-376-0232-7. (página 421)

- "LacusCurtius • Cato — De Agricultura". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- (in Spanish) «[resulta] casi imposible definir, sobre la base de la exposición de Catón, cuando entró en uso tal o cual instrumento, cuándo fue aplicado tal o cual perfeccionamiento»: Kovaliov, Sergei I. (1979). Historia de Roma (Third ed.). Madrid: Akal Editor. ISBN 84-7339-455-0. p. 178

- (in Latin) Rerum Rusticarum de Agri Cultura online in the original Latin

- Varro, Rerum Rusticarum… Liber primus, XII: «Quae nasci in fundo ac fieri a domesticis poterunt, eorum nequid ematur, ut fere sunt quae ex viminibus et materia rustica fiunt, ut corbes, fiscinae, tribula, valli, rastelli…»

- Varro, Rerum Rusticarum… Liber primus, LII. «Quae seges grandissima atque optima fuerit, seorsum in aream secerni oportet spicas, ut semen optimum habeat; e spicis in area excuti grana. Quod fit apud alios iumentis iunctis ac tribulo. Id fit e tabula lapidibus aut ferro asperata, quae cum imposito auriga aut pondere grandi trahitur iumentis iunctis, discutit e spica grana;…»

- Varro, Rerum Rusticarum… Liber primus, LII. «…aut ex axibus dentatis cum orbiculis, quod vocant plostellum poenicum; in eo quis sedeat atque agitet quae trahant iumenta, ut in Hispania citeriore et aliis locis faciunt.»

- De Re Rustica, cap VI: «Area, si competit, ita constituenda est, ut vel a domino vel certe a procuratore despici possit. Eaque optima est silice constrata, quod et celeriter frumenta deteruntur, non cedente solo pulsibus ungularum tribularumque, et eadem ventilata mundiora sunt, lapillisque carent et glaebulis, quas per trituram fere terrena remittit area.»

- Naturalis Historia, Liber XVIII (naturae frugum), lxxii - 298.

- Duby, Georges (1974). The early growth of the European economy. Warriors and Peasants from the Seventh to the Twelfth Century. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9169-X..

- Caro Baroja Julio (1983). Tecnología popular española. Editorial Nacional, Colección Artes del tiempo y del espacio, Madrid. p. 98. ISBN 84-276-0588-9.

- Diocesan archive of Salamanca: «Et yo, donna Mayor, devo dexar a mia muerte estas duas yugadas de heredat devandichas al cabildo bien allinadas, con quatro kafiçes de trigo, et un kafiz de centeno, et un kafiz de cevada pora semiente cada yugada, et con reias, et con arados, et con timones, et con trillos et con todo appayamiento que heredade bien allinnada deve aver»

- Georges Duby, op. cit. page 249: «A través de cuanto hemos dicho se ve el interés que tendría la medición de la incidencia del progreso técnico en el rendimiento de la empresa agrícola. Sin embargo, hay que renunciar a hacerla. Antes de fines del siglo XII, los métodos de la administración señorial son todavía muy primitivos; conceden poca importancia a la escritura y menos aún a las cifras. Los documentos son más decepcionantes que los de la época carolingia»

- E.A.R.T.H., official site.

- González Torices, José Luis y Díez Barrio, Germán (1991). "Capítulo IV, La Trilla". Aperos de madera (in Spanish). Ámbito Ediciones, for the Junta de Castilla y León. pp. 135–161. ISBN 84-86770-48-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)- Caro Baroja Julio (1983). Tecnología popular española (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial Nacional, Colección Artes del tiempo y del espacio. p. 98. ISBN 84-276-0588-9.

- Siguero, Amparo (1984). "Los trilleros". Revista de Folklore (in Spanish). Tomo: 04a (número: 41): 175–180. Caja España. Fundación Joaquín Díaz.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|journal=

- Benito del Rey, Luis y Benito Álvarez, José-Manuel (1995). "Trilleros, en busca del eslabón perdido (I, II y III)". La Frontera del Duero (in Spanish). Año 1 (Números 1, 2 y 3). Depósito Legal, AV 121-1995.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Benito del Rey, Luis y Benito Álvarez, José-Manuel (1995). "Trilleros, en busca del eslabón perdido (I, II y III)". La Frontera del Duero (in Spanish). Año 1 (Números 1, 2 y 3). Depósito Legal, AV 121-1995.

- Benito del Rey; Luis y Benito Álvarez; José-Manuel (1994). "La taille actuelle de la pierre à la manière préhistorique. L'exemple des pierres pour Tribula à Cantalejo (Segovia - Espagne)". Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française. Tome 91 (Numéro 3, mai–juin): 214–222. doi:10.3406/bspf.1994.9770.

- Cuesta Polo, Marciano, coord. (1993). Glosario de Gacería (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Cantalejo, Segovia. p. 5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - VV.AA. (1937). The Story of the Bible. Amalgamated Press.

- Bishop Vincent, John H. (1884). Earthly Footsteps of the Man of Galilee. N.D. Thompson Publishing Co.

Sources

- This article draws heavily on the corresponding article Trillo (agricultura) in the Spanish-language Wikipedia, accessed in the version of 20 November 2006.

External links

- A threshing floor in the hills of Galilee (ca. 1900), Library of Congress

- Early Agricultural Remnants and Technical Heritage (EARTH)

- Patricia C. Anderson, Sound and Science: an approach to the ethnoarchaeology of threshing cereals and pulses, on the EARTH site.

- Reconstruction of a Mesopotamian threshing sledge, reprint from EARTH

- (in French) tribulum: reconstitution d'un traineau à dépiquer mésopotamien: "Threshing board: Reconstruction of a Mesopotamian threshing sledge" (drawings), Centre d'études Préhistorique, Antiquité, Moyen Âge (CEPAM), University of Nice

- Threshing sledges from the Bronze Age and today (CEPAM / Centre de Recherches Archéologiques - CNRS)

- (in Spanish) Día del Mundo Rural 2000 (Rural World Day 2000). Pictures from Miranda de Arga (Navarre, Spain).

- (in Spanish) Laureano Molina Gómez, El trillo del abuelo ("Grandfather's Threshing board"), etnografo.com.

- (in Spanish) Amparo Siguera Los trilleros ("The threshers"), Revista de Folklore; includes some illustrations