Three Worlds Theory

In the field of international relations, the Three Worlds Theory (simplified Chinese: 三个世界的理论; traditional Chinese: 三個世界的理論; pinyin: Sān gè Shìjiè de Lǐlùn) of Mao Zedong proposed to the visiting Algerian President Houari Boumédiène in February 1974 that the international system operated as three contradictory politico-economic worlds. On April 10, 1974, at the 6th Special Session United Nations General Assembly, Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping applied the Three Worlds Theory during the New International Economic Order presentations about the problems of raw materials and development, to explain the PRC's economic co-operation with non-communist countries.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Maoism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series about |

| Imperialism studies |

|---|

|

|

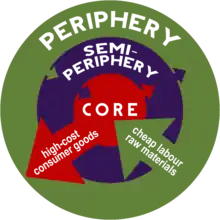

The First World comprises the United States and the Soviet Union, the superpower countries. The Second World comprises Japan, Canada, Europe and the other countries of the global North. The Third World comprises China, India, the countries of Africa, Latin America, and continental Asia.[2]

As political science, the Three Worlds Theory is a Maoist interpretation and geopolitical reformulation of international relations, which is different from the Three-World Model, created by the demographer Alfred Sauvy in which the First World comprises the United States, the United Kingdom, and their allies; the Second World comprises the Soviet Union, the People's Republic of China, and their allies; and the Third World comprises the economically underdeveloped countries, including the 120 countries of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).[3]

Criticism

In the 1970s, the Party of Labour of Albania led by Enver Hoxha began to openly criticize the Three Worlds Theory, describing it as anti-Leninist and a chauvinist theory. These criticisms were elaborated upon at length in works by Enver Hoxha, including The Theory and Practice of the Revolution and Imperialism and the Revolution, and were made also published in the newspaper of the Party of Labour of Albania, Zëri i Popullit. The publication of these works and the now active criticism of the Three Worlds Theory in Albanian media played a hand in the growing ideological divide between Albania and China that would ultimately culminate in Albania denouncing the People's Republic of China and Maoism as revisionist.[4][5][6]

See also

References

- "Excerpts From Chinese Address to U.N. Session on Raw Materials". The New York Times. 1974-04-12. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- Gillespie, Sandra (2004). "Diplomacy on a South-South Dimension". In Slavik, Hannah (ed.). Intercultural Communication and Diplomacy. Diplo Foundation. p. 123.

- Evans, Graham; Newnham, Jeffrey (1998). The Penguin Dictionary of International Relations. Penguin Books. pp. 314–315. ISBN 978-0-14-051397-4.

- Hoxha, Enver (1978). "Imperialism and the Revolution". Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- Hoxha, Enver (1977). "The Theory and Practice of the Revolution". Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- Biberaj, Elez (1986). Albania and China: a study of an unequal alliance. Westview special studies in international relations. Boulder: Westview Pr. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8133-7230-3.