Thomas Ruddiman

Thomas Ruddiman (October 1674 – 19 January 1757) was a Scottish classical scholar.

_-_Thomas_Ruddiman_(1674%E2%80%931757)%252C_Philologist_and_Publisher_-_PG_2013_-_National_Galleries_of_Scotland.jpg.webp)

Life

He was born on a farm near Boyndie, three miles from Banff in Banffshire, where his father was a farmer.[1]

He was educated locally, then studied at the University of Aberdeen. Initially from 1695 he was schoolmaster in Laurencekirk.[2] Then in 1700, through the influence of Dr Archibald Pitcairne, he became an assistant in the Advocates' Library, Edinburgh. He founded (1715) a successful printing business, and in 1728 was appointed printer to the University of Edinburgh. He acquired the Caledonian Mercury in 1729, and in 1730 was appointed keeper of the Advocates' Library, resigning in 1752.[3]

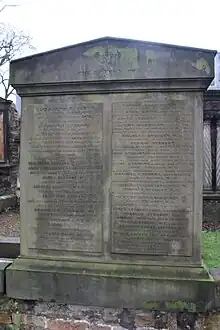

He is buried at Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh. The monument was erected in 1801 by his relative, Dr William Ruddiman.[4] It stands in the north-west section of the graveyard.

Family

He was married to Anna Smith (1694–1769).[5]

His nephew Walter Ruddiman (1719–1781) also from Banff, similarly established a successful business in Edinburgh as a printer and publisher.

Works

His main early writings were editions of Florence Wilson's De Animi Tranquillitate Dialogus (1707), and the Cantici Solomonis Paraphrasis Poetica (1709) of Arthur Johnston (1587–1641), editor of the Deliciae Poetarum Scotorum. On the death of Dr Pitcairne he edited his friend's Latin verses, and arranged for the sale of his valuable library to Peter the Great of Russia.[3]

In 1714 he published Rudiments of the Latin Tongue, which was long used in Scottish schools. In 1715 he edited, with notes and annotations, the works of George Buchanan in two volumes folio. As Ruddiman was a Jacobite, Buchanan's liberal views invited his criticism. A society of scholars was formed in Edinburgh to "vindicate that incomparably learned and pious author from the calumnies of Mr Thomas Ruddiman"; but Ruddiman's remains the standard edition, though George Logan, John Love, James Man and others attacked him with vehemence.[3]

Other works were: An edition of Gavin Douglas's translation of Virgil's Aeneid (1710), with an extensive Older Scots glossary; the editing and completion of James Anderson's Selectus Diplomatum et Numismatum Scotiae Thesaurus (1739); Catalogue of the Advocates' Library (1733–42); and a famous edition of Livy (1751). He also helped Joseph Ames with his Typographical Antiquities.[3]

Ruddiman was for many years the representative scholar of Scotland. Writing in 1766, Dr Johnson, after reproving James Boswell for some bad Latin, significantly adds--"Ruddiman is dead." When Boswell proposed to write Ruddiman's life, "I should take pleasure in helping you to do honour to him", said Johnson.[3]

References

Citations

- Grants Old and New Edinburgh

- Monuments and monumental inscriptions in Scotland: The Caledonian Society of Scotland

- Chisholm 1911.

- Monuments and monumental inscriptions in Scotland: The Caledonian Society of Scotland

- Inscription on tomb

Bibliography

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ruddiman, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 814.

- Ruddiman, Thomas [Thoma Ruddimannus] (1725), Burman, Pieter [Petrus Burmannus] (ed.), Georgii Buchanani, Scoti, Poëtarum sui seculi facile Principis, Praeceptoris Jacobi VI Scotorum, & Primi Angl. Reg. Opera Omnia, Historica, Chronologica, Juridica, Politica, Satyrica & Poetica, J. Arnold Langerak. (in Latin)

- Duncan, Douglas (1965), Thomas Ruddiman: a study in Scottish scholarship of the early eighteenth century, Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd.

External links

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.