Thomas Guy

Thomas Guy (1644 – 27 December 1724) was an English bookseller, member of Parliament, and the founder of Guy's Hospital, London.

Thomas Guy | |

|---|---|

Thomas Guy by John Vanderbank, 1706 | |

| Member of Parliament for Tamworth | |

| In office 1695–1708 | |

| Preceded by | Michael Biddulph, Sir Henry Gough |

| Succeeded by | Richard Swinfen, Henry Girdler |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1644 Southwark, London, England |

| Died | 27 December 1724 (aged 79–80) |

| Occupation | Member of Parliament, bookseller, investor |

| Known for | Founder of Guy's Hospital |

Early life

Thomas Guy was born in Horselydown in Southwark, in south London, the eldest child of a lighterman and coalmonger. Thomas Guy (senior) was a citizen and Carpenter of the City of London, and was an Anabaptist dissenter. His mother, Anne, was the daughter of William Voughton, from a respectable family of the borough of Tamworth in Staffordshire. Thomas Guy (senior) died in 1652, whereupon his widow returned to Tamworth with her children, Thomas (junior), John and Anne, and it was probably in the free grammar school there that the younger Thomas received his education.[1]

London publisher

Thomas returned to London in 1660 and served for eight years as the apprentice of John Clarke the younger of Cheapside, a bookseller and bookbinder. His term of service therefore spanned the age of the Restoration (1660), the Plague year (1665) and the Great Fire (1666). In 1668, he was admitted into the Stationers' Company and made a freeman of the City of London. In the same year he opened a bookstore at the corner of Lombard Street and the Cornhill.[2]

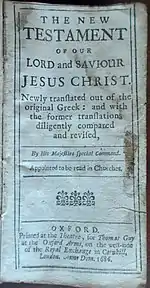

At first, Guy illegally imported bibles printed in the Netherlands, as they were of higher quality than those printed in England. His imprint appears in the fourth edition of James Howell's Epistolae Ho-Elianae, Familiar Letters, Domestic and Forren (1673), and the third edition of John Ogilby's translation of Virgil (1675) was published by him jointly with the London publisher Peter Parker, with whom he shared lists. Parker and Guy were the sellers for John Bond's edition of Horace (1678), and were among the sellers of school-books printed at the Theatre in Oxford, editions of classical texts by Pliny, Homer, Theocritus, Herodian, Cornelius Nepos, Sallust, Quintilian and Maximus Tyrius, and also Thomas Lydiat's Canones Chronologici. Books sold by them printed in London included Elisha Coles's Latin and English Dictionaries, the Colloquia Familiaria of Erasmus, H. Robinson's Scholae Wintoniensis Phrases, Thomas Godwyn's Antiquities, Martial's Epigrams, works of Quintus Curtius, Lucius Florus, Valerius Maximus, Caesar, etc., and also Sir Robert Stapylton's translation of Juvenal's Satires and Thomas May's translation of Lucan's Pharsalia (though these also appear under other imprints).[2]

In most of these publications Guy's name is linked with that of Peter Parker, and in the 1677 edition of Coles's Dictionary John Guy, Thomas's brother, is shown in partnership with him. After the first English Bible to be printed at Oxford was issued in 1673-1675, in 1679 Thomas was contracted by the University of Oxford to produce bibles under their licence. With Parker and Moses Pitt, he was licensed to sell the Oxford 1683 edition of the Book of Homilies, and an Oxford Bible was published under his name in 1679, 1680, 1682, 1683, 1685-1686 and 1687-1688, in various formats. The Oxford prayer-book published by him in 1689 included the forms of prayer and collects for 5 November (for deliverance from the Gunpowder Plot, and also for the Happy Arrival of King William III), for 30 January (martyrdom of King Charles I) and for 29 May (Thanksgiving for the end of the Great Rebellion and Restoration of King Charles II). His later publications include a Theodore Beza bible of 1705. A fuller account of his publications is given by Wilks and Bettany.[2]

Tamworth benefactor and M.P.

A frugal bachelor, after nine years of business, in 1677, he paid for new facilities at the Tamworth free grammar school, where he had been educated before his apprenticeship. The next year, he built an almshouse in Tamworth. He was elected as MP for Tamworth in 1695 and commissioned a new Tamworth Town Hall in 1701. However, when the voters of Tamworth rejected him in 1707, he angrily refused to help them any further.[3][4][5]

Investment in the South Sea Company

By the late 1670s, Guy had begun purchasing seamen's pay-tickets at a large discount, as well as making large loans to landowners. In 1711, these tickets, part of the short-term "floating" national debt, were converted into shares of the South Sea Company in a debt-for-equity swap. The South Sea Company was primarily set up as a government-debt holding company; although it later held a monopoly on British trade to Spanish America, this used less than 2% of the Company's capital.[6] In 1720, before the South Sea Bubble burst, Guy sold 54,040 stock for £234,428, making a profit of about £175,000.[7] He re-invested this money in £179,566 4% government annuities, £8,000 of 5% government annuities, and £1,500 East India Company shares.[8]

Sponsor of hospitals

In 1704, Guy became a governor of St Thomas' Hospital, in London. He gave £1000 to the hospital in 1707 and further large sums later. In 1721, having quintupled his fortune the previous year, he decided to found a new hospital "for incurables." Work on what became Guy's Hospital began in 1721.

Thomas Guy died unmarried on 27 December 1724. Having already spent £19,000 on the hospital, his will endowed it with £219,499, the largest individual charitable donation of the early eighteenth century. He also gave an annuity of £400 to Christ's Hospital as well as numerous and diverse other charitable donations. The rest of his estate, some £75,589, went to cousins, friends, and more distant relatives.[9]

On 24 March 1725, George I gave royal assent to a bill incorporating the executors of Guy's will and formally thanking Guy for helping "the Honour and Good of the publick".[10]

In 1995, 271 years after his death, a new dual carriageway by-passing Tamworth was named Thomas Guy Way in his honour.

Monuments

Parliament allowed Guy's Hospital to spend up to £2,000 to perpetuate Guy's "Generous and Charitable Intentions". In 1732, the administrators commissioned Peter Scheemakers, who created a striking brass and marble statue of Guy in the livery of the Stationers' Company, notably wearing no wig, an indication of Guy's lack of ostentation. The monument includes the motto Dare Quam Accipere ("to give than to receive"), a relief of Christ Healing the Sick Man, and another relief of the Good Samaritan. It stands in the courtyard of the main forecourt of Guy's Hospital.

In 1776, the hospital built a new west wing, including a chapel. The administrators commissioned John Bacon (1740–1799) to sculpt a life-sized marble funerary monument inside it. Bacon's work portrays Guy as "a living Samaritan", helping a sick man. Roundels on the monument contain the figures of Industry, Prudence, Temperance, and Charity.[9]

Bibliography

- A True Copy of the Last Will and Testament of Thomas Guy, Esq. (London, 1725)

- John Noorthouck, 'Book 3, Ch. 1: Southwark', in A New History of London Including Westminster and Southwark (R. Baldwin, London 1773), pp. 678-690, at p. 684 (British History Online, accessed 31 May 2022).

- John Nichols, Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century, 6 vols (Nichols, Son, and Bentley, London 1812), III, p. 599 (Google).

- Charles Knight, Shadows of the Old Booksellers (Bell and Daldy, London 1865), pp. 3–23 (Google).

- Samuel Wilks and G. T. Bettany, A Biographical History of Guy's Hospital (Ward, Lock, Bowden & Co., London/New York 1892); read at Google.

- Copy of the Last Will and Testament of Thomas Guy Esq. with an ACT for incorporating the Executors of the said Will (London, printed for the Governors of Guy's Hospital, 1815); read at Hathi Trust.

- Jane Bowden-Dan, 'Mr Guy's Hospital and the Caribbean', History Today, Vol. 56 issue 6 (June 2006); read at History Today archive (subscription required).

References

- Wilks and Bettany, A Biographical History of Guy's Hospital, pp. 2-3.

- Wilks and Bettany, Chapter II: 'Guy as a London Publisher', in A Biographical History of Guy's Hospital, pp. 8-16 (Google).

- Hervey, Nick (2004). "Guy, Thomas (1644/5?–1724), philanthropist and founder of Guy's Hospital". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11800. Retrieved 10 June 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gardiner, Juliet (2000). The History Today Who's Who in British History. London: Collins & Brown Limited and Cima Books. p. 376. ISBN 1-85585-876-2.

- "Thomas Guy - Tamworth Heritage Trust". Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Dickson, P. G. M. (Peter George Muir) (1993). The financial revolution in England : a study in the development of public credit, 1688–1756. Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Gregg Revivals. ISBN 0-7512-0010-7. OCLC 28695656.

- Odlyzko, Andrew (2019). "Newton's Financial Misadventures in the South Sea Bubble". The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science. 73: 29–59.

- Jones, T. Roy (1 January 1938). "The Holdings of Thomas Guy in the South Sea Company". Baptist Quarterly. 9 (3): 170–183. doi:10.1080/0005576X.1938.11750464. ISSN 0005-576X.

- Solkin, David H. (1 September 1996). "Samaritan or Scrooge? The Contested Image of Thomas Guy in Eighteenth-Century England". The Art Bulletin. 78 (3): 467–484. doi:10.1080/00043079.1996.10786698. ISSN 0004-3079. S2CID 227272839.

- "An Act for Incorporating the Executors of the Last Will and Testament of Thomas Guy, late of the City of London, Esq; Deceased, and others, in Order to the better Management and Disposition of the Charities given by his said Last Will." (11 Geo. 1. c. 12)