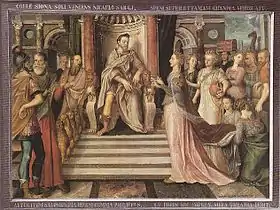

The Queen of Sheba visits King Solomon

The Queen of Sheba visits King Solomon, also known as Solomon and the Queen of Sheba,[1] is a painting by the Flemish painter Lucas de Heere. Dated from 1559, it features a contemporary interpretation of the well-known Biblical story of the Queen of Sheba's state visit to King Solomon (1 Kings 10, 1-13 and 2 Chronicles 9, 1-12). Lettered within image, in lower right: "Lvcas Derys inv. fecit 1559".

| The Queen of Sheba visits King Solomon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Lucas de Heere |

| Year | 1559 |

| Type | oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 183 cm × 260 cm (72 in × 100 in) |

| Location | St Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium |

History

Lucas de Heere painted The Queen of Sheba visits King Solomon in 1559. It was commissioned by chancellor Viglius van Aytta for the Choir of St Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent on the occasion of the celebration of the twenty-third chapter of the Order of the Golden Fleece, which was presided over by Philip II of Spain as grandmaster. The composition was subsequently adopted for a stained glass window by Wouter Crabeth in the Sint Janskerk in Gouda. The original has been conserved in situ in the choir of St Bavo's Cathedral ever since.[2]

Realization

Comparing Philip II of Spain to the Biblical figure of Solomon was a common theme in the years leading up to his reign, and in the early years thereof. As his father, Charles V, was seen as the more warlike David, Philip was viewed as the more temperate Solomon, overlooking his severe idolatry and the killing his half-brother Adonijah,[3] in hopes that he would see the prudence in exercising a degree of religious toleration. In his impassioned speech for a peaceful reconciliation with Protestantism before the English Parliament in 1534, the reform-minded Catholic bishop Reginald Pole said that the appeasing of controversies of religion in Christianity is not appointed to this emperor, but to his son.[4]

After a devastating fire at the Sint Janskerk in the neighboring Gouda in 1552, Philip was one of the first to donate a stained glass window towards the rebuilding, as he had done at St Bavo's upon the occasion of his father's abdication. Habsburg donations such as these were both an expression of piety and a statement of power. The 1557 King's Window by Dirk Crabeth in the north transept is 20 meters high. The top portion depicts The Dedication of the Temple by Solomon. Two years before the painting, Solomon is paraded as the biblical predecessor of Philip, who inherits Solomon's good qualities and abilities by association.[5] Viglius van Aytta was the intermediary between Brussels and Gouda for the reglazing of St John's.

Description

In the painting, Solomon, the ruler of then still intact Kingdom of Israel, is again represented with Philip II's features: with black hair, a beard, a hanging lip and a pronounced chin.[6][7] His attire, including a laurel crown, rather corresponds to that of a Roman emperor, in tune with the Roman temple depicted in the background of his palace.[8] The throne leaves no doubts as to the painting's intention, for it is the famous gold and ivory throne of Solomon, with two lions beside the armrests and six steps (1 Kings 10, 19; and II Chron. 9, 18).[9]

The foreign Queen of Sheba, accompanied by her trusted entourage, came in Jerusalem to visit Solomon, whose wisdom she has heard to be praised. After testing the Jewish king with hard riddles and see the splendor of his court, she recognised the Divine source of Solomon's wisdom, and acknowledged him as her superior, and Solomon gave her everything she wanted.[10] According to some traditions, this indicated a sexual relationship, from which a son later emerged, who would become the ancestor of the Ethiopians.

In a subtle allegory, as his first wife Mary I of England, she represents the Low Countries, therefore belonging to the crown of Spain, which place their riches at the king's disposal in exchange for the latter's just and wise rule. The Queen of Sheba is a tall, red-haired monarch, like the Protestant Queen Elizabeth, who had recently ascended the English throne on the death of her sister Mary.[11] In the words of the Old Testament, after the Queen had witnessed Solomon's glory, there was no more spirit in her. And so Mary wears her Pearl, and her matron's cap. Her once flowing hair is bound up and hidden, but she has been given a greater gift to treasure, the Pearl of Great Price.[12]

A renowned jurist, Erasmian humanist, and advocate of religious peace, Viglius van Aytta was an important member of the Dutch regent Margaret of Parma's inner council in Mechelen, although Margaret herself suspected him of secret non-conformism. It is also significant that Viglius is depicted as the soldier surround the king with his wise councilors at the far left of the composition, symbolizing the pact signed with the Spanish king in occasion of the Joyeuse Entrée in Brabant.[8] The coat of arms of the Knights of the Golden Fleece, which still appear above the stalls of the choir of the church, also come from the brush.

The Latin text from above to below on the frame of the painting emphasises the parallel between Philip II and the biblical king, announcing the use of the Solomonic model in El Escorial: "COLLE SIONA SOLI VENIENS NICAULO SABÆI, SPEM SUPER ET FAMAM GRANDIA MIROR AIT," "ALTER ITEM SALOMON, PIA REGUM GEMMA PHILIPPUS, UT FORIS HIC SOPHIÆ MIRA THEATRA DEDIT." (Coming from the hill Nicaulus, in the land of Sheba, to Zion, she said: "I have seen things much greater than I expected and they had told me."). In the same manner, another Solomon, Philip, pious jewel among kings, gave here and elsewhere amazing examples of his wisdom, as declared by the artist himself.

Assessment

Historian Frances Yates draws a comparison to Holbein's 1534 depiction of Henry VIII of England as Solomon.[13] Belgian art historian Alphonse-Jules Wauters said: "Were we to judge this artist solely from his painting in St. Bavon, Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (1559), we should form but an indifferent idea of his talent."[1]

From 23 March 2018, the work was on display for three months in the Call for Justice exhibition at Museum Hof van Busleyden.[14]

The somewhat later The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession is attributed to Lucas de Heere, who had moved to England, based upon the similarity in the placement of figures, and the mixture of allegory with historical persons.[15]

In popular culture

- A replica of the painting appears in the manor from episode 219 of the anime series Detective Conan, although with an inverted orientation.

References

- Wauters, Alphonse-Jules, The Flemish School of Painting, Cassell Ltd, 1885, p. 168.

- Gerrit Kalff, Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche letterkunde, vol. 3, Groningen, J.B. Wolters, 1907, p. 330.

- Joost vander Auwera, André Tourneux, Jacques Paviot, Interpreting the Universe as Creation, p. 279.

- De Estrella, Diego Calvete, El felicismo viaje del muy alto y muy poderoso principe dom Philippe, vol. 1, Madrid, 1930, p. 422.

- Van Eyck, Xander, Margaret of Parma's gift of a window to St. John's in Gouda and the art of the early counter reformation in the Low Countries

- James, Ralph N., Painters and Their Works, L.U. Gill, 1896, p. 533.

- Marianne Conrads-de Bruin, Het Theatre van Lucas d'Heere Een kostuumhistorisch onderzoek, Utrecht university, 2006, p. 11.

- De la Cuadra Blanco, Juan Rafael, "Lucas of Heere: the queen's visit of Saba to king Salomón (Gante, 1559)", Solomon's Temple in the Low Countries

- The Seventh Window

- "A king and a queen: Solomon and the Queen of Sheba", Pictures of the Bible

- Kevin Ingram, Converso Non-Conformism in Early Modern Spain: Bad Blood and Faith from Alonso de Cartagena to Diego Velázquez, Palgrave, 2018, p. 104-105.

- Veritas Temporis Filia

- Yates, F.A., Valois Tapestries, Routledge, Nov 5, 2013, p. 25. ISBN 9781136353338

- "Over Salomon en Saba". Archived from the original on 2021-09-22. Retrieved 2019-09-13.

- "The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession", National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

Sources

- La Catedral de Gante, Salomón y la reina de Saba (in Spanish)

- Lucas de Heere: La visita de la reina de Saba al rey Salomón (Gante, 1559) (in Spanish)

- Imágenes: La visita de la reina de Saba (in Spanish)

- Lucas de Heere. Visita de la reina de Saba a Salomón. 1559. Catedral de Gante (in Spanish)

- Lucas de Heere (in Dutch)