Lands of Ashgrove

The Lands of Ashgrove, previously known as Ashenyards, formed a small estate in the Parish of Kilwinning, North Ayrshire, lying between Kilwinning and Stevenston. The Georgian mansion house was demolished in 1960,[1] the substantial walled garden survives.

History

The Kings' Road

Portencross Castle is said to have been the last mainland resting place for many of the former kings of Scotland between the reigns of Kenneth I (810–858) and Malcolm III (1030/38-1093). The coffins of these kings were taken by road from Edinburgh via Kilwinning Abbey and what may be an old Roman road[2] to the harbours at Portencross where they were put aboard a boat and taken to Iona in whose sacred grounds where they were laid to rest. Pilgrims would have followed the same route.[3] This 'Avondale Roman Road' may have continued to a harbour at Little Brigurd Point near Hunterston.[4]

The 'Kings' Road'[5] as it is traditionally known, ran from Kilwinning Abbey, through Byres, up through the lands of Ashgrove to take the 'Auld Clay Road' that branches off just before Lochwood and then runs down to near Muirlaught Farm. Armstrong's map of circa 1747 shows that the only direct inland Kilwinning to Portencross road ran along a route that has now largely been abandoned or is now used only by farm vehicles, etc. Armstrong's and other maps show that the route was as follows, modern spellings are in brackets: Kilwinning – Ashgrove – Bankend – the Old Clay Road – Muirlaught – Darleith – Ettington (Meikle Ittington) – Knock (Knockewart) – Edward – Hopeton – Springside – Kilbride (West Kilbride) – Arneal (Auld Hill) – Porting Cross (Portencross).[6] It has been suggested that this road was of Roman origin,[5] the 'Avondale Roman Road',[7] part of which is known later as the 'Haaf Weg' translating as the 'road to the sea' a possible surviving reference being the 'Halfway Street' still to be found in West Kilbride.[3]

The Mansion house and walled garden

Ashgrove House was originally built as a suit of offices, however it was adapted as a large and comfortable dwelling.[8] Ashenyards or Ashinyards is recorded as a farmstead lying to the East and overlooking Ashgrove Loch. Nothing now remains of this dwelling, however the ruins are evident on the 18th century OS maps. The name 'Short Ride Plantation' is given for the one area near the lane to Whitehirst.[9] It is not clear whether Ashgrove was built on a new site or replaced the older laird's dwelling; in 1775 both placenames are recorded on Armstrong's map.[10]

An unusually large walled garden survives and OS maps show that it was once an orchard and contained formal paths, a centrally placed sundial and a greenhouse area. The main entrance had 'white gates' as recorded by locals who took walks along the lane to Whitehirst.[11]

The estate

The lands of Ashinyards, including the wood, comprised between three and four hundred acres of good land. The extent of the woodland policies was a notable feature. One area of woodland is known as the 'Short Ride Plantation' and a former area was known as the 'Long Ride Plantation'.[8] Quhytehirst or Whitehirst, Nether Mains and Auchenkist were at one time part of the estate lands.[12] A wooded belvedere known as the Ashgrove Mount survives to the north of the walled garden. A small wooded roundel was located beyond the Ashenyards farmstead at the intersection of hedgerows.

Cholera pit

An unmarked Cholera pit is situated at the end of the Long Ride Plantation in an area marked on old OS maps as Ladyacre.

The Lairds of Ashgrove

The various sources differ in some details. Robertson gives John Russel as the first recorded owner, selling the lands in 1567 to James Cunninghame of Eisenyards, the first of that designation.[13] James married Margaret Fleming of Barrochan and was succeeded by Alexander, his eldest son. James, brother to Alexander, inherited Eissenyards in 1627. James Cunningham was the chamberlain of Kilwinning and a story is told of him in which he asked Bessie Dunlop's, the witch of Dalry, to help with a case of theft of some barley that was stolen from the barn of Craigends and she was able to tell him where it was. [14]

William Cunninghame of Ashinyards and Whitehurst is next recorded in 1664 and inherited from his father James in 1671.[13] He married Margaret Wilkie and in 1706 their only surviving heir married Andrew Martin of Lochridge near Beith.[12] A son, Arthur Martin, married Isabel Aitchison and moved to the West Indies where he died and his daughters Margaret and Magdalene as co-heiresses, sold the estate to John Bowman in 1766.[15]

Pont records the owner as Alexander Cuninghame and the estate's name as 'Asshin-Zairds'; he comments that the name derives from 'Esch' an ash tree and 'yaird' a measure of an area of land.[16] This branch of the Cuninghame family were derived from the Cuninghames of Craigends who were in turn a cadet branch of the Earls of Glencairn. Andrew Martin of Clochridge (Lochridge near Beith)[17] in 1712 acquired the property from William Cuninghame, his father in law. John Bowman (see below) purchased Ashinyards when Andrew Martin's son was in his minority; he was himself related in the maternal line to the Cuninghames.[18]

Paterson states that the Cuninghame family continuously held Ashinyards from circa 1570[18] until an eldest daughter, Elizabeth Cuninghame, married John Bowman Esq in 1695; who did however, as stated, purchase the estate.[8] John Bowman was a Glasgow merchant, and chief magistrate in 1715.[8] Their son, John Bowman, became Lord Provost of Glasgow and married a Miss Houghton of Dublin in 1734, the couple had two sons and two daughters. When he died in 1796 he left the estate and other properties in the parish to Anne, his eldest daughter, because his eldest son John married and settled in North America, whilst his second son Houghton married a Miss Vere and moved to Dominica. John Bowman changed the name from Ashinyards to Ashgrove.[8]

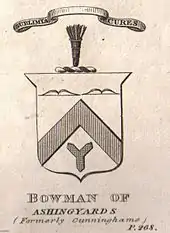

Anne Bowman married Miller Hill Hunt, a captain in the 6th Regiment of Foot who had fought and been wounded at the Battle of Culloden.[8] Captain Hunt died in 1783 and his wife died in 1811. They had three daughters, Maria, Margaret Anne and Elizabeth Ballantyne. Margaret inherited in 1811 as the only surviving heir and changed her name to Bowman, her maternal grandfathers surname, and took his coat of arms.[8] Elizabeth had married Roger Rollo, brother of Lord Rollo, a Collector of Customs in Ayr and had four sons and two daughters.[8] The coat of arms are a classic armorial rebus or pun on the 'Bowman' name with two strung bows and a quiver of arrows. Records show that family members joined the Ancient Society of Kilwinning Archers.

Anne, or Lady Bowman as she was known locally, was succeeded by Andrew FitzJames Cuninghame Rollo-Bowman-Ballantyne of Ashgrove and Castlehill, born, 1835, who was the son of Elizabeth and Roger Rollo, her sister and brother in law.[18] Andrew married Anne Harriet Curzon Chalmers in 1864 and the couple had offspring.[19] The Ballantine family still held the property in the 1930s.

Ashgrove Loch and natural history

Ashgrove Loch, Lochwood Loch, or Stevenston Loch lies to the west of Ashgrove and is recorded as the only mineral enriched mesotrophic loch in North Ayrshire. The area has been extensively drained by means of a deep ditch or "cunnel"[20] and only 10% of the surviving loch is open water; a floating raft of vegetation covers the remainder.

The name 'Loch Canal' on the OS maps is recorded for the Canal or burn from Stevenston Loch that ran to a Sluice at the North side of Lochend. It was called a canal because this section of the Burn or lade was cleaned on a three yearly basis and a sluice was once present that regulated the flow of water to Stevenston Mill.[21]

The loch is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) since 1975 and many interesting plant species, including greater bladderwort, lesser pond sedge, tufted loosestrife, and the nationally rare cowbane have been recorded. Breeding birds include snipe, water rail, grasshopper warbler, and reed bunting. The countryside around Ashgrove Loch is amongst the richest in the area; the fields attract flocks of chaffinch, reed bunting, yellowhammer, and tree sparrow.[22]

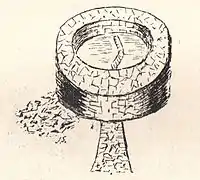

Crannogs

John Smith recorded up to six crannogs in Ashgrove Loch, one, on the eastern side, is said to be unique as a crannog in that it was mainly of a stone rather than the usual timber construction with a causeway built of large sandstone blocks.[20] It is possible that this 'crannog' was actually a dun or mediaeval fort. A considerable number of relics were found, such as chisels, wooden spoons, shears, bone implements, etc.[23] A local tradition holds that the treasures of Kilwinning Abbey were hidden on a crannog in the loch by the monks when the abbey was sacked during the reformation. The proximity of the old 'Kings Road' to Portencross to the site is of interest in this regard.

Micro-history

In 1673 James Cunninghame was appointed as then tutor to Sir William Cunninghame of Cunninghamhead.[17]

James Cunninghame of Ashinyards was a Covenanter and was jailed for 9 months for his refusal to conform.[17][24]

John Bowman Esg of Ashgrove purchased the estate of Montgreenan in 1778, however he later sold the property to Robert Glasgow Esq of Glasgow in 1794.[25]

The 1851 census records that Margaret Ann Bowman Margaret, aged 78 was the landed proprietrix, farming about 130 acres. Alexander Currie was an agricultural labourer at Ashgrove, together with a dairymaid Margaret Macallum and a housemaid, Janet Baillie[26]

A film of Ashgrove in the 1930s exists with a DeHavilland DH-60 Moth aeroplane G-EBUX on display. At the time the property was still owned by the Ballantine family and Monica Ballantine often landed her aircraft on the estate fields near to the house.[27]

Ashgrove House stood derelict for many years and became ruinous prior to its demolition by a local farmer. The foresters cottage was located on an estate lane near to the south west of the house and was rebuilt as a bungalow in the 1930s only to be vandalised when unoccupied and it was subsequently demolished as a result.

A steading known as Ashinyards was located on the hill however this was demolished and the stones removed.

The estate fields were largely planted with turnips and potatoes in the 1940s.

The monks of Kilwinning Abbey traditionally mined coal near to Ashgrove House and a later mine was abandoned due to flooding when the workings dug into the old flooded monk's workings.

An Asiatic Cholera pit is traditionally said to be located near the Long Ride Plantation.

See also

References

Notes;

- Love, Page 53

- Newall, F

- Old Roads of Scotland – West Kilbride Retrieved : 2 March 2014

- Ayrshire Roots Retrieved : 2 March 2014

- Old Roads of Scotland Retrieved 1 March 2014

- Armstrong's Map Retrieved : 1 March 2014

- Old Roads of Scotland

- Paterson, Page 487

- RCAHMS Retrieved : 25 March 2011

- Armstrong's Map Retrieved : 25 March 2011

- Irvine Herald Retrieved : 25 March 2011

- Robertson, Page 264

- Robertson, Page 262

- Henderson, Page 16

- Robertson, Page 265

- Dobie, Page 69

- Robertson, Page 263

- Dobie, Page 70

- Burke's Peerage Retrieved : 25 March 2011

- Smith, Page 45

- Ayrshire OS Name Book, Volume 57

- "Stevenston Conservation". Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- Smith, Page 51

- Records of Parliament Retrieved : 25 March 2011

- Robertson, Page 266

- 1851 census Retrieved : 25 March 2011

- Scran Site Retrieved : 25 March 2011

Sources;

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Glasgow : John Tweed.

- Henderson, L. (ed.) (2009). Fantastical Imaginations: The Supernatural in Scottish History and Culture. Edinburgh : John Donald. ISBN 9781906566029

- Love, Dane (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. Ayr : Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V. – II – Cunninghame. Edinburgh: J. Stillie.

- Newall, F. The Roman Signal Station Fortlet at Outerwards, Ayrshire.

- Robertson, George (1823). A Genealogical Account of the Principal Families in Ayrshire, more particularly in Cunninghame. Irvine.

- Smith, John (1895). Prehistoric Man in Ayrshire. London : Elliot Stock.