The House of Fame

The House of Fame (Hous of Fame in the original spelling) is a Middle English poem by Geoffrey Chaucer, probably written between 1374 and 1385, making it one of his earlier works.[1] It was most likely written after The Book of the Duchess, but its chronological relation to Chaucer's other early poems is uncertain.[2]

| The House of Fame | |

|---|---|

| by Geoffrey Chaucer | |

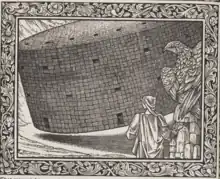

Woodcut by Edward Burne-Jones of the house "made of twigs" from "The House of Fame" | |

| Original title | Hous of Fame |

| Written | c. 1374–85 |

| Illustrator | Edward Burne-Jones (1894 edition) |

| Country | England |

| Language | Middle English |

| Subject(s) | Fame, Greek mythology |

| Genre(s) | Dream vision |

| Meter | Octosyllabic |

| Rhyme scheme | Couplets |

| Media type | manuscript |

| Lines | 2,005 |

| Preceded by | The Book of the Duchess |

| Full text | |

The House of Fame is over 2,005 lines long in three books and takes the form of a dream vision composed in octosyllabic couplets. Upon falling asleep the poet finds himself in a glass temple adorned with images of the famous and their deeds. With an eagle as a guide, he meditates on the nature of fame and the trustworthiness of recorded renown. This allows Chaucer to contemplate the role of the poet in reporting the lives of the famous and how much truth there is in what can be told.

Synopsis

The work begins with a poem in which Chaucer speculates on the nature and causes of dreams. He claims that he will tell his audience about his "wonderful" dream "in full".

Chaucer then writes an invocation to the god of sleep asking that none, whether out of ignorance or spite, misjudge the meaning of his dream.

The first book begins when, on the night of the tenth of December, Chaucer has a dream in which he is inside a temple made of glass, filled with beautiful art and shows of wealth. After seeing an image of Venus, Vulcan, and Cupid, he deduces that it is a temple to Venus. Chaucer explores the temple until he finds a brass tablet recounting the Aeneid.

Chaucer goes into much further detail during the story of Aeneas' betrayal of Dido, after which he lists other women in Greek mythology who were betrayed by their lovers, which led to their deaths. He gives examples of the stories of Demophon of Athens and Phyllis, Achilles and Breseyda, Paris and Aenone, Jason and Hypsipyle, and later Medea, Hercules and Dyanira, and finally Theseus and Ariadne. This prefigures his interest in wronged women in The Legend of Good Women, written in the mid-1380s, which depicts various women of Greek mythology, including Dido, Medea, and Ariadne.

Chaucer finishes recounting the Aeneid from the brass tablet, and then decides to go outside to see if he can find anyone who can tell him where he is. He finds that outside the temple is a featureless field, and he prays to Christ to save him from hallucination and illusion. He looks up to the sky and sees a golden eagle that begins to descend towards him, marking the end of the first book.

When the second book begins, Chaucer has attempted to flee the swooping eagle but is caught and lifted up into the sky. Chaucer faints, and the eagle rouses him by calling his name. The eagle explains that he is a servant of Jove, who seeks to reward Chaucer for his unrewarded devotion to Venus and Cupid by sending him to the titular House of the goddess Fame, who hears all that happens in the world.

Chaucer is skeptical that Fame could possibly hear everything in the world, prompting the eagle to explain how such a thing happens. According to the eagle, the House of Fame is the ‘natural abode’ of sound. The concept of the natural abode was an explanation for how gravity functions: a stone dropped from any height will fall down to reach the ground, smoke will rise into the air, and rivers always lead to the sea. Because sound is "broken air", this means that it is light, which means that it will rise upwards, which means that its natural abode must be in the heavens. The eagle gives further evidence of this by comparing sound to a ripple.

Later, the Eagle offers to tell Chaucer more about the stars, but Chaucer declines, saying he is too old.

They arrive at the foot of the House of Fame at the beginning of the third book, and Chaucer describes what he sees. The House of Fame is built atop a massive rock that, upon closer inspection, turns out to be ice inscribed with the names of the famous. He notices many other names written in the ice that had melted to the point of illegibility, and he deduces that they melted because they were not in the shadow of the House of Fame.

Chaucer climbs the hill and sees the House of Fame and thousands of mythological musicians still performing their music. He enters the palace itself and sees Fame. He describes her as having countless tongues, eyes, and ears, to represent the spoken, seen, and heard aspects of fame. She also has partridge wings on her heels, to represent the speed at which fame can move.

Chaucer observes Fame as she metes out fame and infamy to groups of people who arrive, whether or not they deserve or want it. After each of Fame's judgments, the god of the north winds, Aeolus, blows one of two trumpets: "Clear Laud" to give the petitioners fame or "Slander" to give the petitioners infamy. At one point, a man who is most likely Herostratus asks for infamy, which Fame grants to him.

Soon, Chaucer leaves the House of Fame, and is taken by an unnamed man to a "place where [Chaucer] shall hear many things". In a valley outside of the house, Chaucer sees a large, rapidly spinning wicker house that he guesses to be at least miles in length. The house makes incredibly loud noises as it spins, and Chaucer remarks that "if the house had stood upon the Oise, I believe truly that it might easily have been heard it as far as Rome".

Chaucer enters the house and sees a massive crowd of people, representing the spread of rumor and hearsay. He spends some time listening to all he can, all the lies and all the truth, but then the crowd falls silent at the approach of an unnamed man who Chaucer believes to be of "great authority". The poem ends at this point, and the identity of this man remains a mystery.

The Columns of Fame

The House of Fame is held up by a number of large columns, and standing atop them are a number of famous poets and scholars, who carry the fame of their most prominent stories on their shoulders.

- Josephus, a scholar of Jewish history, standing on a column of lead and iron and holding the fame of the Jewish people. He is accompanied by seven others, unnamed, who help him carry the burden. Chaucer notes that the reason the column is of lead and iron is because they wrote of battles as well as wonders, and iron is the metal of Mars and lead is the metal of Saturn.

- Statius, on an iron pillar covered in tiger’s blood, holding up the fame of Thebes and ‘cruel Achilles’.

- On an iron pillar, holding up the fame of Troy: Homer, Dares, Dictys, "Lollius", Guido delle Colonne, and Geoffrey of Monmouth.

- Chaucer notes some ill-will between them. One claims that “Homer's story was just a fable, and that he spoke lies, and composed lies in his poems, and that he favored the Greeks”.

- Virgil on a column of brightly tinned iron.

- Ovid on a column of copper.

- Sir Lucan on a column of stern iron, holding the fame of Julius and Pompey, accompanied by a number of Roman historians.

- Claudian on a pillar of sulfur, holding the fame of Pluto and Proserpine.

Overview of criticism

The poem marks the beginning of Chaucer's Italian-influenced period, echoing the works of Boccaccio, Ovid, Virgil's Aeneid, and Dante's Divine Comedy.[3] Its three-part structure and references to various personalities suggest that perhaps the poem meant to parody the Divine Comedy. The poem also appears to be influenced by Boethius's The Consolation of Philosophy.[4] The work shows a significant advancement in Chaucer's art from the earlier Book of the Duchess. At the end of the work, the "man of greet auctoritee" who reports tidings of love has been interpreted as a reference to either the wedding of Richard II and Anne, or the betrothal of Philippa of Lancaster and John I of Portugal, but Chaucer's typically irreverent treatment of great events makes this difficult to confirm. Other scholars have put forth the alternative hypothesis that the man of great authority is Elijah, or another of the Hebrew prophets. As with several of Chaucer's other works, The House of Fame is apparently unfinished—although whether the ending was indeed left incomplete, has been lost, or is a deliberate rhetorical device, is uncertain.

The poem contains the earliest known uses in the English language of the terms galaxy and Milky Way:

See yonder, lo, the Galaxyë

Which men clepeth the Milky Wey,

For hit is whyt.— Geoffrey Chaucer The House of Fame, c. 1380.[5]

Adaptations

In 1609, Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones appropriated the image of "The House of Fame" for their "Masque of Queenes" commissioned by Anne of Denmark, James VI and I's queen consort, who performed in the masque. In the eighteenth century, it was adapted by Alexander Pope as The Temple of Fame: A Vision.[6] John Skelton made an earlier emendation to Chaucer's vision of Fame, Rumour and Fortune with his A Garlande of Laurell.

References

- Chaucer, G. (1937). The complete works of Geoffrey Chaucer, pp. 326–348. London: Oxford University Press, Humphrey Milford.

- Lynch, Geoffrey Chaucer ; edited by Kathryn L. (2007). Dream visions and other poems. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393925883.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Benson, general editor, Larry D. (1987). The Riverside Chaucer (3rd ed.). Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0395290317.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lynch, Geoffrey Chaucer; edited by Kathryn L. (2007). Dream visions and other poems. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393925883.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- Pope, Alexander. The Temple of Fame: A Vision. London: Printed for Bernard Lintott, 1715. Print.

External links

- Text, translation and other resources at eChaucer Archived 2019-05-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Chaucer's poem The House of Fame in Modern English prose translation

- The Dream Poems – modernised versions A. S. Kline

.jpg.webp)