The London Merchant

The London Merchant (Or The History Of George Barnwell) is playwright George Lillo's most famous work. A tragedy that follows the downfall of a young apprentice due to his association with a prostitute, it is remarkable for its use of middle and working class characters. First performed at the Drury Lane Theatre on 21 June 1731, The London Merchant became one of the most popular plays of the century.

Sources

George Lillo was born in London on 4 February 1693. By 1730, he began writing plays such as George Barnwell (also known as The London Merchant), Fatal Curiosity, Silvia, and The Country Burial.

George Lillo based The London Merchant on a seventeenth-century ballad about a murder in Shropshire. The ballad follows the adventures of George Barnwell, who engages in an affair with the prostitute Sarah Millwood. After stealing money from his employer to fund his relationship, Barnwell robs and murders his uncle. Both Barnwell and Millwood are arrested and executed for their crimes. Lillo's plays usually resembled drames, or mixed toned Bourgeois Tragedies revolving around the middle-class.[1]

According to Lillo's preface to the play, he was drawn to the subject matter for its moral instruction. Lillo states, "If tragic poetry be. . .the most excellent and most useful kind of writing, the more excellent that piece must be of its kind." He validates his use of middle class characters in "that tragedy is so far from losing its dignity by being accommodated to the circumstances of the generality of mankind that it is more truly August in proportion to the extent of its influence and the numbers that are properly affected by it, as it is more truly great to be the instrument of good to many who stand in need of our assistance than to a very small part of that number."[2]

Lillo may have taken his title The London Merchant as a twist to make real the fictional play featured in Francis Beaumont's Knight of the Burning Pestle.[3] The reuse of the name acknowledges that both plays elevate common citizens as subjects worthy of a play.

Characters

- Thorowgood, a London merchant

- George Barnwell, apprentice to Thorowgood

- Trueman, apprentice to Thorowgood

- Blunt, servant of Millwood

- Barnwell, uncle of George Barnwell

- Maria, daughter of Thorowgood

- Sarah Millwood, a lady of pleasure

- Lucy, servant of Millwood

- Officers with their attendants, keeper of the prison, executioner and footmen

Plot

- Act I

Sarah Millwood, a London prostitute, schemes to find some innocent young man "who, having never injured women, [would] apprehend no injury from them" (I.iii) to seduce and exploit for money. She observes young George Barnwell in town, and she invites him to her house for supper. She realizes that he works for the wealthy merchant Thorowgood (who is known throughout London for his wealth and success). She decides to seduce George Barnwell at supper with irresistible flattery, and he succumbs to her wiles in a way that will give her access to Thorowgood's money, and she manipulates Barnwell to steal from his boss.

- Act II

Upon returning home the next morning, George feels he has betrayed Thorowgood by disobeying his curfew. The guilt he feels from disobeying the rules of the house, as well as the guilt he feels from his fornication with Millwood, leaves George tormented. His guilt is compounded by the loyalty of his friend Trueman. Soon, Millwood visits George at his place of work. When she discovers he no longer wants anything to do with her, she begins to sense her money-making scheme has come to an end. She quickly thinks of a lie to tell George to keep her plan going. She tells George that the man who provides her with housing somehow found out about their tryst and is now evicting her because of it. This evokes new feelings of guilt from George, and he is prompted to steal a large sum of money from his employer's funds to give to her to amend the situation.

- Act III

After giving her the money, George feels unworthy of his kind master, Thorowgood, so he runs away and leaves a note for Trueman confessing his crime. Having no place to go, he turns to Millwood for help. At first she refuses him since his employer's money is no longer at his disposal, but she quickly remembers that he has previously mentioned a rich uncle. She again manipulates George into believing that she truly loves him, and concocts a scheme for him to rob his uncle. George objects, saying that his uncle will recognize him as his nephew; Millwood answers that the only way, then, will be to also murder his uncle. In a fit of passion, George runs off to commit the robbery and murder. He finds his Uncle Barnwell alone, and as he approaches, George veils his face and attacks his uncle with a knife. As he lies dying, Uncle Barnwell prays both for his nephew and his murderer, not knowing that they are the same. Overcome with sorrow, George reveals himself to his uncle, and before he dies, Uncle Barnwell forgives his murderous nephew.

- Act IV

In the meantime, Lucy came to Thorowgood and revealed the truth behind what Barnwell had done. Because of this Thorowgood rushes to exit and tells Lucy she must keep watch on Millwood's house. Later, George returns to Millwood's home upset, trembling, and with bloody hands. Upon realizing that he did not take any money or property, Millwood sends for the police and has George arrested for murder. Two of Millwood's servants, Lucy and Blunt, who were aware of the plan from the beginning, have her arrested as well. Both George and Millwood are sentenced to death. In the last scene of Act 4 Millwood expresses to Thorowgood that she is not remorseful in the least bit saying, "I hate you all! I know you, and expect no mercy -- nay, I ask for none. I have done nothing that I am sorry for. I followed my inclinations, and that the best of you does every day. All actions are alike natural and indifferent to man and beast who devour or are devoured as they meet with others weaker or stronger than themselves."

- Act V

Millwood blamed society and men for what she has become. She is not remorseful at all and with passion accepts her fate. Despite all that has transpired, George is visited by Thorowgood and Trueman in his prison cell. They console and forgive him. Thorowgood provides for his spiritual needs by arranging a visit from a clergyman. In the end, George is truly repentant for his sins and is at peace with himself, his friends, and God. Trueman ends the show with a small monologue saying, "In vain with bleeding hearts and weeping eyes we show a human gen'rous sense of others' woe, unless we mark what drew their ruin on, and, by avoiding that, prevent our own" (Act V Sc. X) to show that the play was to learn how to do the right things in our own lives.

Themes

- Morality and Ethics

Morality in the theater was an important issue during the Restoration and eighteenth century. The Killigrew and Davenant Patents are similar documents which gave the guidelines for the reopening of theaters in London, granting the rights of one theater to each. The Killigrew Patent describes that "no new play shall be acted … containing any passages offensive to piety and good manners" (Patent). Many felt that plays from earlier periods, including those of Shakespeare, exhibited bold vulgarity. Producers strove to remove these aspects from theater to ensure that the audience did not model themselves after the immoral decisions of characters. The London Merchant follows this general trend and goes further to include a moral message intended to be learned by apprentices watching the play. In the dedication to "The London Merchant", Lillo argues that "Plays founded on moral tales in private life may be of admirable use by carrying conviction to the mind with such irresistible force as to engage all the faculties and powers of the soul in the cause of virtue, by stifling vice in its first principles." Tejumola Olaniyan states that Lillo is effective in ensuring that the audience should learn from the play.[4] He suggests that due to accounts from Thorowgood, Trueman, and Maria, as well as evidence from his actions in the play, Barnwell is at his essence a good character despite his crimes, and the audience should sympathize with and learn from him.[4]

Olaniyan argues that the ethics in the play are "supernatural," meaning that they are timeless. Morals do not exist for people, but people exist for the morals.[4] This is significant because it means that the individual is subservient to the system. As a part of the absolutist system, each member must contribute to these ethics and is allowed no individuality in them.[4] This is important for then-contemporary audiences, who by watching the play would learn their place within society. Within the supernatural ethics of the play, Barnwell has no hope as soon as he smiles at Millwood as he sees her on the street for the first time.[4] He is unable to eradicate this error, and any attempts he makes to fix his situation end up making it worse. He digs himself into a deeper hole until eventually he commits the ultimate crime of murdering his uncle. Millwood is another character who operates within this scheme of ethics. In a system that allows for no deviation, she is the deviation.[4] Because of this, she is not offered the same "redemption" that is granted to Barnwell at the end of the play, as he is accepted by Trueman and dies respected by other characters.[4]

- Status of the Merchant

Lillo emphasizes the central role of the merchant in society, showing that the merchant class has a level of what Peter Hynes calls "cultural legitimacy".[5] The upper classes of the eighteenth century struggled to decide where to place merchants in society, and many looked down upon them. At the same time, merchants strove to emphasize their gentility.[4] Daniel Defoe argued that the trade of the merchants and the land of the elites were codependent, supporting and supplying one another with necessities.[4] Olaniyan argues that the play glorifies mercantile ideals such as empire, peace, and patriotism, and also asserts the importance of the merchant in holding society together; the merchant builds the empire and helps ensure the peace.[4] Thorowgood draws attention to these key aspects of the merchant throughout the text with statements such as "honest merchants, as such, may sometimes contribute to the safety of their country as they do at all times to its happiness"(Act I, scene i).

Important to the emphasis on the merchant's role is the genre of the play. The London Merchant is an early example of bourgeois tragedy. Tragedy, which had been a genre reserved for elite and royal subjects, has now been applied to the middle class. Lillo says in the dedication to the play that "tragedy is so far from losing its dignity by being accommodated to the circumstances of the generality of mankind.". What he refers to as "the end of tragedy" functions by "exciting the passions in order to the correcting of them". By bringing tragedy to the level of the middle class, he allows it to have a powerful message that the audience can learn from. This significant shift in tragedy is similar to the change in comedy made by Richard Steele's The Conscious Lovers, a play that refined sensibility in comedy and depicted the middle class as modern gentry[6] The London Merchant asserts the ethics of the merchant, creating Thorowgood as a character who exemplifies all of the desired values that a merchant should have.[5]

- Exchange and Excess

While exchange and trade are important issues to the merchant, they are also key factors in the text itself as they become metaphors throughout the play. Imperial commerce was growing in the eighteenth century, and Thorowgood describes this phenomenon as a circulation throughout the world.[5] For example, he tells Trueman in act three that he should study trade because he can learn "how it promotes humanity as it has opened and yet keeps up an intercourse between nations far remote from one another in situation, customs, and religion"(Act III, scene i).

Key moments of the play, such as the bond between Barnwell and Trueman in act five, are put into the language of exchange. Barnwell describes their union as an "intercourse of woe" instructing Trueman to "pour all your griefs into my breast and in exchange take mine" (Act V, scene ii). While there are obvious homoerotic implications to this dialogue, its presence in the play shows how the exchange created by merchants helps to sustain society.

In addition to exchange, another economic element that serves as a metaphor in the play is excess, which is most strongly exhibited through passion.[5] While Barnwell begins by following calm commerce, a passionate lust replaces it with the theft from Thorowgood and murder of Barnwell's uncle. Hynes describes that the most dangerous thing about passion is its insatiability, because "erotic love, unlike trade, includes no machinery of impulse and abatement, no way of rationally regulating itself".[5] While trade can easily sustain itself, passion has nothing stopping it from going to the extreme. Millwood also embodies this excess, as her absolutism political ideology defies all aspects of sustainability through exchange.[5] In this way she exploits contracts, simulating behavior of exchange, but really in order to defy the entire system.

- Apprenticeship

The application of the tragic genre to the middle merchant class comes with new identity structures for the audience, namely that of apprenticeship.[7] Apprenticeship was very popular at the time of this play, as there were 10-20,000 apprentices in the city of London. One day each year, usually around Easter, all of the apprentices were taken to the theater and shown a play for apprentice day. Beginning around the year 1675, the play shown on this day was called The London Cuckolds. This play was about three businessmen whose wives cheat on them with their apprentices. Soon it was felt that the play gave a poor moral message to the apprentices. In 1731, Lillo's play was performed for the first time for apprentices, and it continued to be played on such an occasion every year until 1819, perhaps the last time that the play was staged for many decades. The London Merchant, through the eyes of masters, would be an instructive play for apprentices because it shows how important it is for them to obey their masters.

Apprenticeships were both educational and economical exchanges.[7] In terms of economics, two men would exchange a young man, and with him came money to pay for his training, food, and boarding. The apprentice was taken into the home of the master and became a member of his family; the master became a type of surrogate father for the apprentice. During the beginning of an apprenticeship, the master might lose money because the apprentice is not capable of performing a trade well enough for a profit, but towards the end of an apprenticeship, the master would actually make money. At times, this was a faulty system. A master might sometimes dismiss an apprentice for "misconduct" and then keep the money.[7] He may also be reluctant to teach the apprentice too well, because then he would only be creating more competition for himself. Thorowgood does not display any of these poor habits. Lillo has created him as an ideal master, similar to how he is the ideal example of proper exchange and trade. The play emphasizes his kindness and mercy as a master instead of his disciplinary function.[7] As a master should, he is a surrogate father for Barnwell. He cries at the end of the play over Barnwell's death, a fatherly gesture.[7]

Apprenticeship was also very much a gender-based institution.[7] Women could also be apprentices, but the field was mostly dominated by men. Not only does Barnwell form a strong bond with Thorowgood, but also with Trueman, another apprentice. One example of this is at the end of the play as Barnwell and Trueman hold one another.[7] A strong moral bond develops between the men in the play, which is something that would have been a desirable message for the audience of that time.[7] A fraternity grows between men, and the female Millwood is not allowed to take part in this.[7] However, her comments to Barnwell about her regrets of her sex upon their first meeting suggest that she longs to take part in such a brotherhood.[7] Because she is denied admittance, she tries to get revenge by severing all such ties that Barnwell has (Thorowgood, his uncle), putting him into the same position as her.

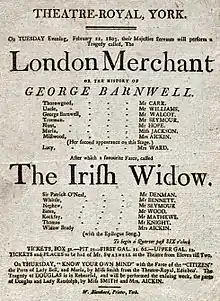

Productions

The original Drury Lane cast included Theophilus Cibber as George Barnwell, Roger Bridgewater as Thorowgood, William Mills as Trueman, Jane Cibber as Maria and Charlotte Charke as Lucy.[8]

The London Merchant was staged ninety-six times from 1731 to 1741.[9] Although not performed as frequently as the most famous play of the period, John Gay's The Beggar's Opera, The London Merchant was extremely popular with English theatergoers of the time, it was later performed regularly until 1819 at the Christmas and Easter holidays as a cautionary entertainment for apprentices.[10] Lillo's play was so popular that it was performed for Queen Caroline and George II by request on a number of occasions, the Queen requesting a copy of the script.[11] In more recent years the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds staged the play in 2010.

On November 14, 1751, George Washington saw a production of the play in Bridgetown, Barbados, during the only international trip of his life. He remarked in his diary after watching the play, "The character of Barnwell and several others were said to be well perform'd."[12] Historians believe this the first play that Washington ever saw performed.[13]

Analysis

The story is adapted from the ballad, George Barnwell, but the plot has been modified to strengthen its connection to the urban lower classes. The focus of the story is an apprentice, or member of the "makers class." These young men were not taught the skills of the master, and many turned to a life of crime to support themselves. However, the master in this play, Thorowgood, is not only fair and kind to his apprentices, he treats them with dignity and respect as well, and the apprentice is led to a life of crime through the actions of a talented seductress, Sarah Millwood. The London Merchant provided a tempered breakdown of a complicated social issue and simplified it into a parable about personal loyalty and sexual appetite, making it easy for the masses to identify with the characters.[14]

Due to Lillo's use of extended prose and long speeches in praise of the merchant class, as well as the "melodramatic" plot elements, there is a great deal of prose and not a lot of substance given to the bulk of the characters, with the exception of Millwood and possibly Lucy.[15] However, the play was an oddity when it was published as well, being quite unlike anything published before or after it. The London Merchant marked the introduction of the bourgeois tragedy. Where tragedies had previously been reserved for the nobility, Lillo brought the concept to the everyman character and further complicated his idea by including the situation of acquisition through exchange, rather than through conquest.[15] The idea of exchange ties heavily to the pro-merchant/ master theme of the play, as Thorowgood is a merchant and a good master. The play also provides a portrait of the model apprentice in the character of Trueman, who is juxtaposed with George Barnwell in an effort to demonstrate proper apprentice behavior as well as warn the many apprentices who were expected to be in attendance of the dangers of disobeying their masters.

The theater commonly gave plays produced especially for the apprentice audience on selected days throughout the year. These plays generally contained an apprentice character that represented the audience and was constructed as someone with whom they could identify.[16] In the case of The London Merchant, there were two such characters, George Barnwell and Trueman. Lillo presented these two as the dichotomy of the apprentice class. The one, Trueman, was a model apprentice, as evidenced by his name, and George Barnwell was presented as the apprentice led astray by the wiles of women, serving as a warning to apprentices everywhere that even a small act of disobedience, breaking the master's curfew, could lead to the unthinkable, murder. The fact that apprentices were encouraged to attend these plays was frowned upon by larger society as they felt that apprentices would abandon their businesses in pursuit of entertainment and would learn unacceptable behavior from the characters in the plays.[16] However, in truth, plays like The London Merchant were for the edification of the masters and the merchant class and sought to demonstrate "model behavior" to the apprentices, although the idea that apprentices were truly sneaking away from their posts en masse and enjoying other interests to the detriment of business is questionable.[16]

The London Merchant originally closed with a gallows scene that Lillo was encouraged by his associates to cut from the production of the play. The scene was a reflection of the high number of public executions taking place at the time. During the eighteenth century, six times a year, the government would execute a large number of people at Tyburn for the crime of theft. This practice was especially prevalent during the 1720s. These hangings disproportionately featured people belonging to the poor, lower class, many of whom were former apprentices. There were a number of scuffles during these executions between government representatives and the public as they tried to prevent both the hangings as well as the removal of the bodies.[17] There are a number of theories regarding the removal of this scene. Among them are the fact that the bourgeoisie did not wish to expose the brutality that was primarily the result of a class pushed to thievery because of the treatment they received from the upper class. It was also a very literal interpretation of the harsh discipline of the day which many of these apprentices had witnessed firsthand. Another theory is simply that the scene would have been too "entertaining" for the ideas that it attempted to portray to come across properly.[16] Although published with some versions of the play, this scene was not staged in a production of The London Merchant until the Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds's 2010 production in-the-round.[18]

Polly Fields' work examines The London Merchant through the lens of the economic theories of the time and those that Lillo was known to subscribe to. The play focuses on the effects that capitalism has had on people who are its victims through no fault of their own, but through accidents of birth and gender. One of, if not the only character that Lillo truly expands is Millwood, a woman who uses her body and her wits to convince George Barnwell to steal and even kill to supply her with money. Barnwell is shown to be Millwood's victim, but in the larger picture of the society he presents, Lillo shows Millwood to be the victim of capitalism. She is the embodiment of agency in the play as her actions cause the plot to move forward and also expand Lillo's economic critiques in the play. Lillo's background as a jeweler gave him a unique perspective on the economy as he was a solid member of the bourgeois class and an avid participant in capitalism.

Millwood rebels against the hierarchy of women in society as well as women in business. Her rebellion continues to death, as the last scene in which she appears in the regular text is a scathing criticism of the hierarchy and hypocritical nature of men and the economy. In the gallows scene that was removed for most productions, a repentant George Barnwell urges Millwood to change her ways, to which she replies that she "was doomed before the world began to endless pains and (Barnwell) to joys eternal".[15] In Lillo's world of trade, Millwood's commodity is her body; however, she refuses to be "victimized as a woman and a whore."[17] Therefore, Millwood is a more compelling candidate to wear the title of The London Merchant, than even Thorowgood, the ostensibly eponymous merchant. This is reinforced with the opening scene in the play where Millwood entices George Barnwell, and Lucy, is standing nearby as an apprentice, quietly watching her master and learning the trade. Lucy also serves in much the manner of Trueman, to give the audience the character of the life that this successful merchant leads, filled with "fine linens and furniture", further solidifying her role as the merchant and the subversion of the economic order of the day that Lillo illustrates with her character. (Fields, 1999)

Lillo's work reinforces bourgeois values while changing the face of eighteenth-century theater with a tragedy of the middle class. The London Merchant outlines the primary case of the day: the plight of the apprentice. However, through the character of Millwood, he is able to expand his agenda to include the effects of capitalism on women in society as well. These ideas were the primary impetus behind the success of the play both during its time and as an important play to be examined by modern dramatists and economics alike.

Literary and scholarly references

Thomas Skinner Surr adapted the play into the three-volume novel George Barnwell, published in 1798.[19]

The use of The London Merchant as a tale for the moral edification of apprentices is satirized by Charles Dickens in Great Expectations. Pip is subjected by Mr Wopsle and Mr Pumblechook to a reading of "the affecting tragedy of George Barnwell" in which Pip is stung by their "identification of the whole affair with my unoffending self".

In On Liberty, philosopher John Stuart Mill mentions Barnwell's murder of his uncle to illustrate the grounds for punishing wrongdoing: "George Barnwell murdered his uncle to get money for his mistress, but if he had done it to set himself up in business, he would equally have been hanged."[20]

Notes

- Gainor, p. ?

- The London Merchant in Gainor, pp. ?–?

- Burleson, Noyce Jennings (August 1968). "The Knight of the Burning Pestle: A Showcase of Burlesque Techniques" (PDF). ttu-ir.tdl.org. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Olaniyan, Tejumola. "The Ethics and Poetics of a "Civilizing Mission": Some Notes on Lillo's The London Merchant", English Language Notes, pp. 34–39

- Hynes, Peter. "Exchange and Excess in Lillo's London Merchant". University of Toronto Quarterly, 72.3 (2003), pp. 679–97

- Freeman, Lisa A. "Introduction to "Conscious Lovers"", Introduction, The Broadview Anthology of Restoration & Early Eighteenth-Century Drama, Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview (2001), p. 762

- Cole, Lucinda. "The London Merchant and the Institution of Apprenticeship", Criticism, 37.1 (1995), p. 57

- Emmett Langdon Avery. The London Stage, Volume III: A Calendar Of Plays, Entertainments And Afterpieces, Together With Casts, Box Receipts And Contemporary Comment. Southern Illinois University Press, 1961. p.147

- McBurney, William, ed. (1965). The London Merchant. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803253650.

- McNally, Terrence James (1968). "The Problem of the Perennial Popularity of the London Merchant by George Lillo". Dissertations. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "The Gentleman's Magazine, July 1731". July 1731. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Thursday, 14 November 1751". rotunda.upress.virginia.edu. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- Quoted in Hayes, Kevin J. (2017). George Washington: A Life in Books. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780190456672.

- DeRitter, J. (1987). "A Cult of Dependence: The Social Context of The London Merchant", Comparative Drama, pp. 374–86

- Faller, L. (2004). Introduction to The London Merchant. In J. D. Canfield, The Broadview Anthology of Restoration and Eighteenth Century Drama: Concise Edition (p. 847). Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press.

- O'Brien, J. (2004). Harlequin Britain: Pantomime and Entertainment, 1690-1760, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Burke, H. (1994), "The London Merchant and Eighteenth Century British Law", Philological Quarterly, pp. 347–66.

- Morley-Priestman, Anne. "The London Merchant (Bury St Edmunds)", What'sOnStage, 1 October 2010, accessed 7 December 2011

- Skinner, T. S.; Lillo, G. (1798). George Barnwell: A novel. In three volumes. London: H.D. Symonds. OCLC 83305445. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty. p. 153.

References

- Gainor, J. Ellen, Stanton B. Garner, Jr., and Martin Puchner, eds. (2009). The Norton Anthology of Drama: Vol. 1: Antiquity Through The Eighteenth Century. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)