The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys

The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys is a 2002 American comedy-drama film directed by Peter Care and written by Jeff Stockwell and Michael Petroni based on Chris Fuhrman's 1994 semi-autobiographical coming-of-age novel of the same name.[3] The film stars Emile Hirsch, Kieran Culkin, Jena Malone, Jodie Foster and Vincent D'Onofrio.

| The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys | |

|---|---|

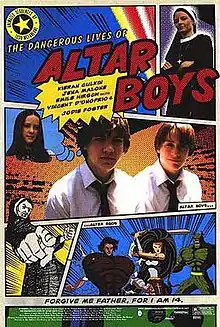

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Care |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys by Chris Fuhrman |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Lance Acord |

| Edited by | Chris Peppe |

| Music by | Marco Beltrami |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | THINKFilm |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 104 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million[1] |

| Box office | $2 million[2] |

The film is about a group of Catholic school friends in the Southern United States in the 1970s who engage in a series of pranks and general mischief. The boys also collaborate on a comic book they call The Atomic Trinity. Interspersed within the film are segments of animated footage based on the comic book.[3]

Fuhrman died of cancer before completing the final revision of the novel.[4] The film, dedicated to his memory, received positive reviews from critics.

Plot

Set in the early 1970s in the city of Savannah, Georgia, the film follows the lives of protagonist Francis Doyle, and three of his friends, Tim Sullivan, Wade Scalisi and Joey Anderson. The four boys all attend a private Catholic school named St. Agatha's, which they detest. The boys rebel by smoking pot, drinking, obsessing over girls, listening to hard rock music and playing pranks on their teachers, such as stealing their school's statue of St. Agatha and keeping it in their clubhouse. The four friends dedicate much of their time to a comic book of their own creation titled The Atomic Trinity in order to escape the monotony and avoid the difficulties in their own lives.

After receiving a love note from Francis, which was actually written by Tim, Margie Flynn becomes a major presence and weaves her way into the lives of these four friends. She and Francis have an obvious connection that progresses into much more. At times, Francis must choose between his friends and Margie, which causes the group of friends to fall apart. The boys' lives are also translated into segments of animation based on the characters of The Atomic Trinity: Brakken, The Muscle, Captain Asskicker and Major Screw; Nunzilla, based on their peglegged, overly repressive Catholic school teacher Sister Assumpta; and Sorcerella, based on Margie Flynn.

After a school field trip to the zoo, Tim and Francis have the idea of playing another prank on Sister Assumpta. They decide to drug the cougar at the local zoo and then transport it to Sister Assumpta's office to scare her. When they learn how serious Tim and Francis are, the other half of the Atomic Trinity wimp out, which leaves an unlikely group of friends consisting of Margie, Tim and Francis. Francis soon learns that Margie had been sexually assaulted by her own brother, Donny. During gym class Donny bullies Tim. Tim, out of pressure and his own impulsive nature, insults Donny for molesting his own sister. He regrets telling Donny, who beats him up, and then tells Francis who becomes angry with him. Donny takes Tim and Francis's comic, The Atomic Trinity, and gives it to the nun. The violent, blasphemous and inappropriate drawings in the notebook cause Tim and Francis to be suspended, pending expulsion from the school.

In an act of final retribution, Tim, Francis, Wade and Joey attempt to steal a cougar to place inside the school to cover up a wrecking of the school they did that night. At the zoo, a makeshift tranquilizer created from several narcotic drugs is used to put the cougar to sleep. The other three boys go down to the gate to retrieve the cougar in a cage, while Tim impulsively climbs over the fence into the cougar's den. He checks to see if the cougar is alive, and happily replies that it is. When the other boys reach the gate to retrieve the cougar, another cougar leaps at Tim, mauling him to death. At Tim's funeral, Francis quotes the poem "The Tyger" by William Blake, whom Sister Assumpta earlier condemned as a "dangerous thinker". Francis places the book at the stolen statue of St. Agatha in their hideout, and starts a new comic series dedicated entirely to the character based on Tim, Skeleton Boy.

Cast

- Emile Hirsch as Francis Doyle

- Kieran Culkin as Tim Sullivan

- Jena Malone as Margie Flynn

- Jodie Foster as Sister Assumpta

- Vincent D'Onofrio as Father Casey

- Jake Richardson as Wade Scalisi

- Tyler Long as Joey Anderson

- Arthur Bridges as Donny Flynn

Production

In order to adapt the book effectively, director Care and producer Jay Shapiro decided to use segments of animation throughout the film. Since most of the book is from Francis' perspective and takes place in his mind, they needed to find a way to stay true to this "internal narrative". "Animation seemed like a natural way to go in and out of this interior world and use that as the thread that ties everything together," said Shapiro.[5] The sequences were created by Todd McFarlane,[3] and they are visually similar to basic superhero comic strips. Screenwriter Jeff Stockwell helped to create the storyline for the animated sequences.

Cinematography is done by Lance Acord, who also worked on Being John Malkovich and Buffalo '66. Production design was done by Gideon Pointe, who also worked on Buffalo '66, as well as American Psycho.[5]

Casting

The filmmakers said that Emile Hirsch was the first actor they had in mind for the Francis character, as he had the "innocence and naivete" that they were looking for. Similarly, filmmakers believed that Kieran Culkin had a similar personality to Tim. "I think he is going through a lot of similar things [in his own life]," stated Jodie Foster, producer and star of the film.[5]

Neither the filmmakers nor Foster had planned on her also playing the part of the stern Catholic school teacher and headmistress, Sister Assumpta, as well as being a producer. Foster was drawn to the role, and called producing partner Meg LeFauve up with a request to play the part. LeFauve graciously accepted, saying that it's not "traditional casting to see a young beautiful woman in that kind of a role."[5]

Setting

Although the novel by Chris Fuhrman is set in 1970s Savannah, Georgia, the filmmakers wanted a more "universal look" and decided not to specify a place. Principal photography took place in North and South Carolina,[3][6] and lasted from May to July 2000.[7] There was also a lot of debate about whether the characters should have Southern accents, but to keep with this "universal feeling," the producers decided against any strong accents.[5]

Soundtrack

The soundtrack was composed by Marco Beltrami and was released in 2002 by Milan Records.[8] Several songs were specifically written and performed for the film by Queens of the Stone Age lead singer Joshua Homme.[9]

- "The Atomic Trinity" – Joshua Homme

- "The Atomic Trinity vs. Heaven's Devils" – Marco Beltrami

- "The Empty House" – Marco Beltrami

- "The Couch" – Marco Beltrami

- "Hanging (aka Ramble Off)" – Joshua Homme

- "Margie's Confession" – Marco Beltrami

- "The Atomic Trinity vs. Heaven's Devils, Round II" – Marco Beltrami

- "St. Agatha" – Marco Beltrami

- "On the Road Again" – Canned Heat

- "Francis and Margie" – Joshua Homme

- "Stoned" – Joshua Homme

- "Dead Dog, Part II" – Marco Beltrami

- "Skeleton Boy is Born" – Marco Beltrami

- "Do for the Others" – Stephen Stills

- "Story of the Fish" – Marco Beltrami

- "For the Gods / Act Like Cougars" – Marco Beltrami

- "Torn Apart" – Marco Beltrami

- "Someone is Coming" – Marco Beltrami

- "Eulogy" – Marco Beltrami

- "All the Same" – Joshua Homme

Reception

Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a rating of 76% based on 106 reviews, with an average rating of 6.5/10. The website’s critics consensus states: "The inter-cutting of animation by Spawn's creator, Todd McFarlane, doesn't always work, but the performances by the young actors capture the pains of growing up well."[10] On Metacritic, which assigns a weighted mean rating out of 100 reviews from film critics, the film has a score of 69 out of 100, based on 31 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[11]

Stephen Holden of The New York Times called it a "bracingly truthful" coming-of-age film that "digs into the flaming recesses of the adolescent mind with such acuity, compassion and good humor that it will plummet you back to that painfully awkward age".[3] Holden noted that "the movie struggles to compare the boys' comic-book vision with William Blake's Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, [which becomes] its one glaringly off-key note."[3]

Roger Ebert gave the film two and a half stars out of four, calling it "an honorable film with good intentions."[12] Ebert went on to say that the screenplay is trying too hard to impress and falls short of achieving the "emotional payoff" it is searching for.[12]

A vocal fan of the animated sequences was Armond White of New York Press, who singled them out for praise.[13]

Accolades

In 2002, director Care won the award for Best New Filmmaker from the Boston Society of Film Critics.[14] In 2003, the film won the Independent Spirit Award for Best First Feature.[15]

References

- "The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys". The Numbers.

- "The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys". Box Office Mojo.

- Holden, Stephen (June 14, 2002). "Film Review: Altar Boys Will Be Altar Boys, and They're Drawing Comics, Too". The New York Times.

- "The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys." Barnes & Noble. 10 February 2015.

- Care, Peter (director) (November 5, 2002). The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys (DVD). Culver City, CA: Sony Pictures.

- "The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys - Movies Filmed in South Carolina". www.sciway.net. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- "The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys". Star-News. October 13, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- "The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys Original Soundtrack". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- "The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys Soundtrack". Soundtrack Collector. 2002.

- "The Dangerous Lives Of Altar Boys". Rotten Tomatoes.

- "The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys". Metacritic. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- Ebert, Roger (June 21, 2002). "The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys". RogerEbert.com.

- White, Armond (June 25, 2002). "Scooby-Doo; The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys". New York Press.

- "Boston crix key up 'Pianist'". Variety. December 15, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- "'Heaven' tops Indie Spirit Awards". Variety. March 22, 2003. Retrieved February 10, 2023.