The Cask of Amontillado

"The Cask of Amontillado" (sometimes spelled "The Casque of Amontillado" [a.mon.ti.ˈʝa.ðo]) is a short story by the American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in the November 1846 issue of Godey's Lady's Book. The story, set in an unnamed Italian city at carnival time, is about a man taking fatal revenge on a friend who, he believes, has insulted him. Like several of Poe's stories, and in keeping with the 19th-century fascination with the subject, the narrative follows a person being buried alive – in this case, by immurement. As in "The Black Cat" and "The Tell-Tale Heart", Poe conveys the story from the murderer's perspective.

| "The Cask of Amontillado" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Edgar Allan Poe | |

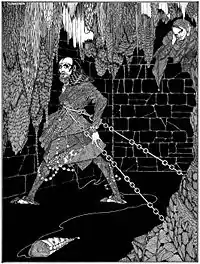

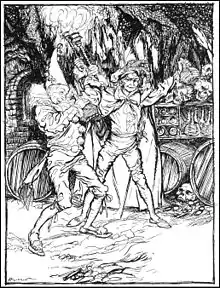

Illustration of "The Cask of Amontillado" by Harry Clarke, 1919 | |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Horror short story |

| Publication | |

| Publication type | Periodical |

| Publisher | Godey's Lady's Book |

| Media type | Print (Magazine) |

| Publication date | November 1846 |

Montresor invites Fortunato to sample amontillado that he has just purchased without proving its authenticity. Fortunato follows him into the Montresor family vaults, which also serve as catacombs. For unknown reasons, Montresor seeks revenge upon Fortunato and is actually luring him into a trap, entombing him alive within the catacombs. At the end of the story, Montresor reveals that 50 years have passed since he took revenge and Fortunato's body has not been disturbed.

Scholars have noted that Montresor's reasons for revenge are unclear and that he may simply be insane. However, Poe also leaves clues that Montresor has lost his family's prior status and blames Fortunato. Further, Fortunato is depicted as an expert on wine, which Montresor exploits in his plot, but he does not display the type of respect towards alcohol expected of such experts. Poe may have been inspired to write the story by his own real-life desire for revenge against contemporary literary rivals. The story has been frequently adapted in multiple forms since its original publication.

Plot summary

The story's narrator, a nobleman named Montresor, describes his revenge against fellow noble Fortunato. Angry over numerous injuries and an unspecified insult, Montresor resolves to avenge himself without being caught, and also to make sure that Fortunato knows he is responsible.

During the annual Carnival season, Montresor finds a drunken Fortunato and asks for his help in authenticating a recently purchased pipe (about 130 gallons, or 492 litres) of what has been described to him as Amontillado wine. As the two descend to the wine cellars and catacombs beneath Montresor's home, Montresor expresses concern over Fortunato's persistent cough and the effect that the dampness will have on his health. An undeterred Fortunato presses on, intent on sampling the Amontillado, and Montresor gives him more wine to keep him inebriated. Montresor describes his family coat of arms: a golden foot in a blue background crushing a snake whose fangs are embedded in the foot's heel, with the motto Nemo me impune lacessit ("No one provokes me with impunity"). At one point, Fortunato makes a gesture that Montresor does not recognize and deduces that Montresor is not a mason. Montresor shows him a trowel as a joke, deliberately confusing Freemasonry with the profession of stonemasonry.

They arrive at a niche deep within the catacombs, where Montresor claims the Amontillado is stored. When Fortunato ventures inside, Montresor chains him to the wall, having devised the Amontillado ruse to lure him into this trap. Montresor sets to work walling up the niche, using supplies of stone and mortar he had previously hidden nearby. Fortunato quickly sobers up and tries to escape, but Montresor mocks his cries for help, knowing that no one can hear them. While Montresor continues to work, Fortunato tries to persuade Montresor to release him, first by suggesting that they treat the incident as a practical joke, and finally making one last desperate plea. As he falls silent, Montresor completes the wall and moves a pile of bones to hide it, feeling a sickness of heart that he dismisses as a reaction to the dampness of the catacombs.

Stating that the niche and Fortunato's body have stood undisturbed for 50 years, Montresor concludes his account by saying, "In pace requiescat!" ("May he rest in peace!").

Publication history

"The Cask of Amontillado" was first published in the November 1846 issue of Godey's Lady's Book,[1] which was, at the time, the most popular periodical in America.[2] The story was only published one additional time during Poe's life, in the November 14, 1846 New England Weekly Review.[3]

Analysis

Although the subject matter of Poe's story is a murder, "The Cask of Amontillado" is not a tale of detection like "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" or "The Purloined Letter"; there is no investigation of Montresor's crime and the criminal himself explains how he committed the murder. The mystery in "The Cask of Amontillado" is in Montresor's motive for murder. Without a detective in the story, it is up to the reader to solve the mystery.[4] From the beginning of the story, it is made clear that Montresor has exaggerated his grievances towards Fortunato. The reader is led to assume that much like his exaggerated grievances, the punishment he chooses will represent what he believes is equal justice, and in turn, going to the extreme.[5]

Montresor never specifies his motive beyond the vague "thousand injuries" and "when he ventured upon insult" to which he refers. Some context is provided, including Montresor's observation that his family once was great (but no longer so), and Fortunato's belittling remarks about Montresor's exclusion from Freemasonry. Many commentators conclude that, lacking significant reason, Montresor must be insane, though even this is questionable because of the intricate details of the plot.[4]

There is also evidence that Montresor is almost as clueless about his motive for revenge as his victim.[6] In his recounting of the murder, Montresor notes, "A wrong is unredressed when retribution overtakes its redresser. It is equally unredressed when the avenger fails to make himself felt as such to him who has done the wrong". After Fortunato is chained to the wall and nearly entombed alive, Montresor merely mocks and mimics him, rather than disclosing to Fortunato the reasons behind his exacting revenge. Montresor may not have been entirely certain of the exact nature of the insults for which he expected Fortunato to atone.[6]

Additional scrutiny into the vague injuries and insults may have to do with a simple matter of Montresor's pride and not any specific words from Fortunato.[7] Montresor comes from an established family. His house had once been noble and respected, but has fallen slightly in status. Fortunato, as his name would seem to indicate, has been blessed with good fortune and wealth and is, therefore, viewed as unrefined by Montresor; however, this lack of refinement has not stopped Fortunato from surpassing Montresor in society, which could very well be the "insult" motive for Montresor's revenge.[7]

There is indication that Montresor blames his unhappiness and loss of respect and dignity within society on Fortunato.[8] It is easy to ascertain that Fortunato is a Freemason, while Montresor is not, which could be the source of Fortunato's recent ascension into upper class society. Montresor even imparts this blame to Fortunato when he states, "You are rich, respected, admired, beloved; you are happy, as once I was". This interchanging of fortunes is a suggestion that, since the names Montresor and Fortunato mirror one another, there is a psychological reciprocal identification between victim and executioner.[8] This identification reciprocity is further suggested when one takes into consideration that Montresor entombs Fortunato in the Montresor family catacombs rather than dispatching him elsewhere in the city amidst the chaos of the Carnival. It is with this converging of the two characters that one is able to see the larger symbolism of the Montresor crest – the foot steps on the serpent while the serpent forever has his fangs embedded in the heel.[8]

Upon further investigation into the true nature of character, double meaning can be derived from the Montresor crest.[6] It is the position of Montresor to view himself as the owner of the righteous foot that is crushing the insolent Fortunato serpent and his "thousand injuries" that progress into insult. A more allegoric meaning of Poe's places the actors in reverse.[6] The blind oaf Fortunato has unintentionally stepped upon the snake in the grass – the sneaky and cunning Montresor – who, as a reward for this accidental bruising, sinks his fangs deep into the heel of his offender, forever linking them in a form of mutual existence.[6]

Though Fortunato is presented as a connoisseur of fine wine, his actions in the story make that assumption questionable. For example, Fortunato comments on another nobleman being unable to distinguish amontillado from sherry when amontillado is in fact a type of sherry, and treats De Grave, an expensive French wine, with very little regard by drinking it in a single gulp. Because intoxication interferes with critical evaluation, and would be avoided by a connoisseur during a wine tasting, it is implied within the story that Fortunato is merely an alcoholic. Under this interpretation, Fortunato's fate could also have been retribution for wasting a bottle of fine wine.[9]

Immurement, a form of imprisonment, usually for life, in which a person is placed within an enclosed space with no exit, is featured in several other works by Poe, including "The Fall of the House of Usher", "The Premature Burial", "The Black Cat", and "Berenice".

Inspiration

An apocryphal legend holds that the inspiration for "The Cask of Amontillado" came from a story Poe had heard at Castle Island (South Boston), Massachusetts, when he was a private stationed at Fort Independence in 1827.[10] According to this legend, he saw a monument to Lieutenant Robert Massie. Historically, Massie had been killed in a sword duel on Christmas Day 1817 by Lieutenant Gustavus Drane, following a dispute during a card game.[11] The legend states other soldiers then took revenge on Drane by getting him drunk, luring him into the dungeon, chaining him to a wall, and sealing him in a vault.[12] This version of Drane's demise is false; Drane was courtmartialled for the killing and acquitted,[11] and lived until 1846.[13] A report of a skeleton discovered on the island may be a confused remembering of Poe's major source, Joel Headley's "A Man Built in a Wall",[14] which recounts the author's seeing an immured skeleton in the wall of a church in Italy.[15] Headley's story includes details very similar to "The Cask of Amontillado"; in addition to walling an enemy into a hidden niche, the story details the careful placement of the bricks, the motive of revenge, and the victim's agonized moaning. Poe may have also seen similar themes in Honoré de Balzac's La Grande Bretèche (Democratic Review, November 1843) or his friend George Lippard's The Quaker City, or The Monks of Monk Hall (1845).[16] Poe may have borrowed Montresor's family motto Nemo me impune lacessit from James Fenimore Cooper, who used the line in The Last of the Mohicans (1826).[17]

Poe wrote his tale, however, as a response to his personal rival Thomas Dunn English. Poe and English had several confrontations, usually revolving around literary caricatures of one another. Poe thought that one of English's writings went a bit too far, and successfully sued the other man's editors at the New York Mirror for libel in 1846.[18] That year, English published a revenge-based novel called 1844, or, The Power of the S.F. Its plot was convoluted and difficult to follow, but made references to secret societies and ultimately had a main theme of revenge. It included a character named Marmaduke Hammerhead, the famous author of "The Black Crow", who uses phrases like "Nevermore" and "lost Lenore", referring to Poe's poem "The Raven". This parody of Poe was depicted as a drunkard, liar, and an abusive lover.

Poe responded with "The Cask of Amontillado", using very specific references to English's novel. In Poe's story, for example, Fortunato makes reference to the secret society of Masons, similar to the secret society in 1844, and even makes a gesture similar to one portrayed in 1844 (it was a signal of distress). English had also used an image of a token with a hawk grasping a snake in its claws, similar to Montresor's coat of arms bearing a foot stomping on a snake – though in this image, the snake is biting the heel. In fact, much of the scene of "The Cask of Amontillado" comes from a scene in 1844 that takes place in a subterranean vault. In the end, then, it is Poe who "punishes with impunity" by not taking credit for his own literary revenge and by crafting a concise tale (as opposed to a novel) with a singular effect, as he had suggested in his essay "The Philosophy of Composition".[19]

Poe may have also been inspired, at least in part, by the Washingtonian movement, a fellowship that promoted temperance. The group was made up of reformed drinkers who tried to scare people into abstaining from alcohol. Poe may have made a promise to join the movement in 1843 after a bout of drinking with the hopes of gaining a political appointment. "The Cask of Amontillado" then may be a "dark temperance tale", meant to shock people into realizing the dangers of drinking.[20]

Poe scholar Richard P. Benton has stated his belief that "Poe's protagonist is an Englished version of the French Montrésor" and has argued forcefully that Poe's model for Montresor "was Claude de Bourdeille, comte de Montrésor (Count of Montrésor), the 17th-century political conspirator in the entourage of King Louis XIII's weak-willed brother, Gaston d'Orléans".[21] The "noted intriguer and memoir-writer" was first linked to "The Cask of Amontillado" by Poe scholar Burton R. Pollin.[21][22]

Further inspiration for the method of Fortunato's murder comes from the fear of live burial. During the time period of this short story some coffins were given methods of alerting the outside in the event of live entombment. Items such as bells tied to the limbs of a corpse to signal the outside were not uncommon. This theme is evident in Fortunato's costume of a jester with bells upon his hat, and his situation of live entombment within the catacombs.[8]

Poe may have known bricklaying through personal experience. Many periods in Poe's life lack significant biographical details, including what he did after leaving the Southern Literary Messenger in 1837.[23] Poe biographer John H. Ingram wrote to Sarah Helen Whitman that someone named "Allen" said that Poe worked "in the brickyard 'late in the fall of 1834'". This source has been identified as Robert T. P. Allen, a fellow West Point student during Poe's time there.[24]

Adaptations

- In 1944, the syndicated radio anthology series The Weird Circle aired an episode based on the story, in which Montresor is depicted as being kidnapped and sold into years of slavery by agents hired by Fortunato, who steals his fiancée and wealth in his absence, as motive for entombing Fortunato alive. The author of the adaptation was not credited.

- On October 11, 1949, the Suspense television show aired an adaptation titled "A Cask of Amontillado", starring Bela Lugosi as "General Fortunato".[25]

- In 1951, EC Comics published an adaptation in Crime Suspenstories #3, under the title "Blood Red Wine." The adaptation was written by Al Feldstein, with art by Graham Ingels and a cover by Johnny Craig. The ending was changed from Poe's original to show the murderer drown in wine moments after the crime, due to the walled-up man having shot the vats of wine before being walled up, while aiming for the murderer. It was reprinted in 1993 by Russ Cochran.

- In 1951, Gilberton's Classics Illustrated #84 featured a faithful adaptation, with art by Jim Lavery. It has been reprinted multiple times over the years.

- In 1953, classical composer Julia Perry wrote a one act opera based on the story entitled The Bottle.[26]

- In 1959, 'The Cask of Amontillado' was retold through a Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar Episode, entitled The Cask of Death Matter. The episode was broadcast on May 24, 1959, and starred Bob Bailey as the eponymous Johnny Dollar.

- In 1960, Editora Continental (Brazil) published an adaptation in Classicos De Terror #1 by Gedeone Malagola.

- Roger Corman's 1962 anthology film Tales of Terror combines the story with another Poe story, "The Black Cat".[27] This loosely adapted version is decidedly comic in tone, and stars Peter Lorre as Montresor (given the name Montresor Herringbone) and Vincent Price as Fortunato Luchresi. The amalgamation of the two stories provides a motive for the murderer: Fortunato has an affair with Montresor's wife.

- In 1970, Vincent Price included a solo recitation of the story in the anthology film An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe. The production features Montresor recounting the story to an unseen guest in a vast, empty dining room.

- "The Merciful", a 1971 episode of Night Gallery, features the story with a twist: an old couple in a basement, with the wife (Imogene Coca) building the wall and quoting from the Poe story, while the husband (King Donovan) sits passively in a rocking chair. Once she has finished, he gets up from the chair and walks up the stairs. The wife has sealed herself in.

- In 1975, CBS Radio Mystery Theater did an extended adaptation which invented new details not original to the story, episode number 203, January 12, 1975.

- In 1976, The Alan Parsons Project released an album titled Tales of Mystery and Imagination with one of the tracks called "The Cask of Amontillado".

- In 1995, American Masters aired an episode called "Edgar Allan Poe: Terror Of The Soul", which included a 15-minute adaptation of the story starring John Heard as Montresor and René Auberjonois as Fortunato. This short film is notable for being an almost word-for-word adaptation of the story.

- "The Cask of Amontillado" was made into a British film in 1998, directed by Mario Cavalli, screenplay by Richard Deakin and starring Anton Blake as Montresor and Patrick Monckton as Fortunato.[28]

- In 2003, Lou Reed included an adaptation on the extended edition of his Poe-themed album The Raven, titled "The Cask" and performed by Willem Dafoe (as Montresor) and Steve Buscemi (as Fortunato).

- Edgar Allan Poe's The Cask of Amontillado (2011) stars David JM Bielewicz and Frank Tirio, Jr. It was directed by Thad Ciechanowski, produced by Joe Serkoch, by production company DijitMedia, LLC/Orionvega. It was a winner of 2013 regional Emmy Award.[29]

- In 2013, Lance Tait's stage adaptation located the action of the story in Nice, France.[30]

- in 2014, Keith Carradine starred in Terroir, a feature-length film adaptation by John Charles Jopson.

- In 2014, the Comedy Bang! Bang! TV series included a parody adaptation in a segment titled "Tragedy is Comedy Plus Slime" in their Halloween episode with Wayne Coyne. In this version, Fortunato is kept alive and is paid as the show's head writer while remaining immured.

- The fourth episode in season 9 American Masters titled Edgar Allan Poe: Terror of the Soul adapts the story.[31]

- On October 17, 2017, Udon Entertainment's Manga Classics line published The Stories of Edgar Allan Poe, which included a manga format adaptation of "The Cask of Amontillado". It was planned to release in Spring 2017.[32]

- In 2023, Mike Flanagan's adaptation of The Fall of the House of Usher, the story is one of many of Poe's works loosely borrowed throughout. It is used as the foundation of the Usher Empire. In the series, antagonist Fortunato is renamed Rufus Griswold, CEO of Fortunato. Madeline and Roderick Usher are substitutes for the narrator. Resolving to murder Rufus for the takeover of the family company resulting in their parents dying penniless and the Usher's growing up in squalor as orphans. They ultimately succeed by means that parallel the story of The Cask of Amontillado.

References

- Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. Checkmark Books. p. 45. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

- Reynolds, David F. (1993). "Poe's Art of Transformation: 'The Cask of Amontillado' in Its Cultural Context". In Silverman, Kenneth (ed.). The American Novel: New Essays on Poe's Major Tales. Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-521-42243-4.

- "Edgar Allan Poe – 'The Cask of Amontillado'". The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore.

- Baraban, Elena V. (2004). "The Motive for Murder in 'The Cask of Amontillado' by Edgar Allan Poe". Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature. 58 (2): 47–62. doi:10.2307/1566552. JSTOR 1566552. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14.

- "The Poe Decoder - "The Cask of Amontillado"". www.poedecoder.com. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- Stepp, Walter (1976). "The Ironic Double In Poe's 'The Cask of Amontillado'". Studies in Short Fiction. 13 (4): 447.

- St. John Stott, Graham (Winter 2004). "Poe's 'The Cask of Amontillado'". Explicator. 62 (2): 85–88. doi:10.1080/00144940409597179. S2CID 163083602.

- Platizky, Roger (Summer 1999). "Poe's 'The Cask of Amontillado'". Explicator. 57 (4): 206. doi:10.1080/00144949909596874.

- Cecil, L. Moffitt (1972). "Poe's Wine List". Poe Studies. 5 (2): 41. doi:10.1111/j.1754-6095.1972.tb00193.x.

- Bergen, Philip (1990). Old Boston in Early Photographs. Boston: Bostonian Society. p. 106.

- Vrabel, Jim (2004). When in Boston: a time line & almanac. Northeastern University. ISBN 1-55553-620-4 / ISBN 1-555-53621-2 p. 105

- Wilson, Susan (2000). Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 37. ISBN 0-618-05013-2.

- "Battery B, 4th U.S. Light Artillery – First Lieutenants of the 4th U.S. Artillery".

- Headley, J. T. (1844). "A Man Built in a Wall". Letters from Italy. London: Wiley & Putnam. pp. 191–195.

- Mabbott, Thomas Ollive, editor. Tales and Sketches: Volume II. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2000. p. 1254

- Reynolds (1993), pp. 94–5.

- Jacobs, Edward Craney (1976). "Marginalia – A Possible Debt to Cooper". Poe Studies. 9 (1): 23. doi:10.1111/j.1754-6095.1976.tb00266.x.

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper Perennial. pp. 312–313. ISBN 0-06-092331-8.

- Rust, Richard D. (2001). "Punish with Impunity: Poe, Thomas Dunn English and 'The Cask of Amontillado'". The Edgar Allan Poe Review. 2 (2): 33–52. JSTOR 41508404.

- Reynolds (1993), pp. 96–7.

- Benton, Richard P. (1996). "Poe's 'The Cask of Amontillado': Its Cultural and Historical Backgrounds". Poe Studies. 30 (1–2): 19–27. doi:10.1111/j.1754-6095.1997.tb00089.x.

- Pollin, Burton R. (1970). "Notre-Dame de Paris in Two of the Tales". Discoveries in Poe. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 24–37.

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper Perennial. pp. 129–130. ISBN 0-06-092331-8.

- Thomas, Dwight; Jackson, David K. (1987). The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, 1809–1849. New York: G. K. Hall & Co. p. 141. ISBN 0-7838-1401-1.

- "A Cask of Amontillado". IMDb. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- Julia Perry. Grove Music Online. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe, A to Z: the essential reference to his life and work. New York City: Facts on File. p. 28. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X. OCLC 44885229.

- "The Cask of Amontillado (1998)". IMDb. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "2013 Emmy Winners". www.natasmid-atlantic.org. National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- Caridad, Ava (2016). "Lance Tait: The Black Cat and Other Plays: Adapted from Stories by Edgar Allan Poe". The Edgar Allan Poe Review. Penn State University Press. 17 (1): 66–69. doi:10.5325/edgallpoerev.17.1.0066. JSTOR 10.5325/edgallpoerev.17.1.0066. p. 67.

- "Edgar Allan Poe: Terror of the Soul". IMDb. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "Udon Ent. to Release Street Fighter Novel, Dragon's Crown Manga". Anime News Network. July 21, 2016.

External links

- Full text in the bound volume of Godey's Lady's Book, Vol. XXXIII, No. 5, November, 1846, pp. 216-218.

- "The Cask of Amontillado" – Full text of the first printing, from Godey's Lady's Book, 1846

- Full text on PoeStories.com with hyperlinked vocabulary words.

- Free-to-download MP3 dramatisation of the story (Yuri Rasovsky)

The Cask of Amontillado public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Cask of Amontillado public domain audiobook at LibriVox