Ta' Braxia Cemetery

Ta' Braxia Cemetery (Maltese: Iċ-Ċimiterju ta' Braxa) is a cemetery in Gwardamanġa, located near the boundary between Pietà and Ħamrun, Malta. It was built between 1855 and 1857 as a multi-denomination burial ground primarily intended for British servicemen, partially replacing a number of earlier 18th century cemeteries. The site also incorporates a Jewish cemetery which was established in around 1830. The cemetery's construction was controversial since the local ecclesiastical authorities were opposed to a multi-faith extra-mural cemetery.

| Ta' Braxia Cemetery | |

|---|---|

Iċ-Ċimiterju ta' Braxa | |

Funerary monuments at Ta' Braxia Cemetery | |

| Details | |

| Established | October 1857 |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 35°53′24″N 14°29′52″E |

| Find a Grave | Ta' Braxia Cemetery |

The cemetery was designed by the Maltese architect Emanuele Luigi Galizia. It was expanded a number of times during the 19th century, and in 1893–94 a memorial chapel dedicated to Lady Rachel Hamilton-Gordon was added. The chapel was designed by the English architect John Loughborough Pearson in a combination of the Gothic Revival and Romanesque Revival styles.

History

Ta' Braxia Cemetery is located just outside the Floriana Lines, the outer fortifications of Malta's capital Valletta.[1] The first cemetery on this site was established in 1778, and it was known as the Cemetery of the Sacra Infermeria.[1] This was the first extra-mural cemetery in Malta.[2] The site also contained some other old cemeteries, including a plague cemetery[3] and a Jewish cemetery which was established in around 1830.[4] By the middle of the 19th century, the area had "become a heath, covered with a heap of rubbish, thorns and nettlebrushes... a common field laid waste without even a central cross or chapel as prescribed by the ritual of the Catholic Church."[2]

By 1850, the British wanted to establish a multi-faith cemetery for servicemen who died in Malta, after the Msida Bastion Cemetery became full.[3] The decision was taken to re-lay and extend the cemetery at Ta' Braxia, which was chosen due to its proximity to the main urban centres of Valletta and the Three Cities.[3] The cemetery was said to be meant for "all religions without distinction"[5] but this only referred to different Christian denominations, excluding other religions,[3] although the pre-existing Jewish cemetery would eventually be incorporated as a separate section into Ta' Braxia.[4] The construction of the cemetery was perceived as a move to establish a predominantly Protestant cemetery.[6]

The establishment of the cemetery was intended to promote extra-mural burial for the upper classes.[2] At the time, the concept of having an extra-mural cemetery was controversial since traditionally people were buried inside churches or chapels.[2] The local ecclesiastical authorities were particularly opposed to extra-mural cemeteries.[2] Further controversy arose since the church was strongly opposed to having a mixed-rite cemetery.[7]

The cemetery was designed by the Maltese architect Emanuele Luigi Galizia, and it was his first major government project.[7] Galizia would later design two other major cemeteries: the Catholic Addolorata Cemetery and the Muslim Turkish Military Cemetery.[8] Work on the cemetery commenced in 1855, with the construction of the boundary walls.[3] The military authorities had to approve its designs so as to ensure that the cemetery would not compromise the fortifications.[3] It officially opened in October 1857, and the opening was not reported in local media.[7] The alteration of an adjacent road in 1861 led to the relocation of a nearby Catholic burial ground and permitted the cemetery's expansion.[3] A southward expansion was undertaken in 1879, and another major expansion took place in 1889.[3]

The cemetery became the main burial ground for the British garrison during the second half of the 19th century.[3] Three bodies recovered from the SS Sardinia disaster in 1908 were buried at Ta' Braxia.[9] The Commonwealth War Graves Commission cares for the graves of eight Commonwealth soldiers buried in the cemetery, five from World War I and three from World War II.[10]

During World War II, aerial bombardment damaged or destroyed some of the headstones and funerary monuments at the cemetery.[11] Other monuments have been damaged due to erosion.[3] Din l-Art Ħelwa and the government set up a committee to restore the cemetery in 2000.[11] An association known as Friends of Ta' Braxia was set up in 2001, and it is responsible for the maintenance and restoration of the cemetery, with the assistance of Din l-Art Ħelwa.[11] Today the cemetery is open to the public on weekdays.[10]

Architecture

The cemetery has a grid layout, with the main entrance gate aligned on the central axis.[3] It originally had a symmetrical layout, but this element has been lost due to later expansions of the cemetery.[3] Internal gateways and retaining walls delineate different sectors within the cemetery.[3] The cemetery includes Greek and Jewish sections,[11] and a fountain which was designed by Galizia can also be found inside.[3]

The cemetery's architecture is not particularly impressive in itself,[5] but it contains a number of elaborate funerary monuments carved out of stone or marble.[3] Their style ranges from neoclassical to ornate and eclectic.[3] Some monuments have iconography denoting Masonic connections.[3]

Chapel

The main landmark at Ta' Braxia Cemetery is the Lady Rachel Hamilton-Gordon Memorial Chapel,[12] which was built to commemorate the wife of Sir Arthur Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Baron Stanmore. While en route from Ceylon to Britain, Lady Hamilton-Gordon fell ill and died in Malta, being buried at Ta' Braxia on 28 January 1889.[3] Sir Hamilton-Gordon commissioned a leading English architect, John Loughborough Pearson, to design a memorial chapel for his wife.[3] Pearson probably never visited Malta, but prepared the plans which were sent to the island.[3] The chapel's foundation stone was laid down on 28 May 1893[7] and it was completed in 1894.[6]

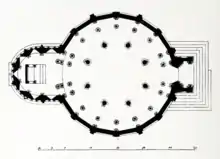

The chapel's architecture cannot be categorically classified as belonging to one particular style, since it combines elements from both the Gothic Revival and Romanesque Revival styles.[7] It has a centralized circular plan with a dome.[3] The external façades contain elaborate geometric decoration and ornamentation, which contrast with the relatively plain dome.[7]

See also

- Pietà Military Cemetery, which is located nearby

References

- Savona-Ventura, Charles (2015). Knight Hospitaller Medicine in Malta [1530–1798]. Self-published. p. 60. ISBN 9781326482220.

- Savona-Ventura, Charles (2016). Contemporary Medicine in Malta [1798–1979]. Self-published. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9781326648992.

- Thake, Conrad (Summer 2011). "Ta' Braxia Cemetery – An architectural appraisal" (PDF). Treasures of Malta. 51: 10–17.

- "Malta: historic Jewish cemetery gets clean-up". Jewish Heritage Europe. 25 July 2016. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018.

- Borg, Malcolm (2001). British Colonial Architecture: Malta, 1800-1900. Publishers Enterprises Group. pp. 86–87. ISBN 9789990903003.

- Cassar, Daphne (26 February 2018). "Did you know that Ta' Braxia cemetery in Pietà had caused huge uproar?". TVM. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018.

- Hughes, Quentin; Thake, Conrad (2005). Malta, War & Peace: An Architectural Chronicle 1800–2000. Midsea Books Ltd. p. 72. ISBN 9789993270553.

- "Three main cemeteries in Malta built by the same man". The Malta Independent. 11 November 2012. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016.

- "The Tragic end of the 'Maltese Titanic'". The Malta Independent. 7 October 2012. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020.

- "Ta-Braxia Cemetery". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018.

- "Ta' Braxia Cemetery, Pieta". Din l-Art Ħelwa. 6 October 2011. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- Cini, George (5 October 2011). "Message in a bottle". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018.

Further reading

- Thake, Conrad; Buhagiar, Janica (2018). Ta' Braxia Cemetery. Midsea Books. ISBN 9789995711702.