Greeks in Syria

The Greeks in Syria arrived in the 7th century BC and became more prominent during the Hellenistic period and when the Seleucid Empire was centered there. Today, there is a Greek community of about 4,500 in Syria, most of whom have Syrian nationality and who live mainly in Aleppo (the country's main trading and financial centre), Baniyas, Tartous, and Damascus, the capital.[1] There are also about 8,000 Greek-speaking Muslims of Cretan origin in Al-Hamidiyah.

History

Greek presence is attested from early on, and in fact, the name of Syria itself is from a Greek word for Assyria.[2]

Iron Age

Further Information: Late Bronze Age collapse

The Ancient Levant had been initially dominated by a number of indigenous Semitic speaking peoples; the Canaanites, the Amorites and Assyrians, in addition to Indo-European powers; the Luwians, Mitanni and the Hittites. However, during the collapse of the Late Bronze Age, the coastal regions came under attack from a collection of nine seafaring tribes known as the Sea Peoples. The transitional period is believed by historians to have been a violent, sudden and culturally disruptive time. During this period, the Eastern Mediterranean saw the fall of the Mycenaean Kingdoms, the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and Syria,[3] and the New Kingdom of Egypt in Syria and Canaan.[4]

Among the Sea Peoples were the first ethnic Greeks to migrate to the Levant. At least three of the nine tribes of the Sea Peoples are believed to have been ethnic Greeks; the Denyen, Ekwesh, and the Peleset, although some also include the Tjeker. According to scholars, the Peleset were allowed to settle the coastal strip from Gaza to Joppa becoming the Philistines. While the Denyen settled from Joppa to Acre, and the Tjeker in Acre. The political vacuum, which resulted from the collapse of the Hittite and Egyptian Empire's saw the rise of the Syro-Hittite states, the Philistine, and Phoenician Civilizations, and eventually the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Al-Mina was a Greek trading colony.

Hellenistic Age

Further Information: Wars of Alexander the Great, Seleucid Empire, Coele-Syria

The history of Greeks in Syria traditionally begins with Alexander the Great's conquest of the Persian Empire. In the aftermath of Alexander's death, his empire was divided into several successor states, and thus ushering in the beginning of the Hellenistic Age. For the Levant and Mesopotamia, it meant coming under the control of Seleucus I Nicator and the Seleucid Empire. The Hellenistic period was characterized by a new wave of Greek colonization.[5] Ethnic Greek colonists came from all parts of the Greek world, not, as before, from a specific "mother city".[6] The main centers of this new cultural expansion of Hellenism in the Levant were cities like Antioch, and the other cities of the Tetrapolis Seleukis. The mixture of Greek-speakers gave birth to a common Attic-based dialect, known as Koine Greek, which became the lingua franca throughout the Hellenistic world.

The Seleucid Empire was a major empire of Hellenistic culture that maintained the pre-eminence of Greek customs in which a Greek political elite dominated, in newly founded urban areas.[7][8][9][10] The Greek population of the cities who formed the dominant elite were reinforced by emigration from Greece.[7][8] The creation of new Greek cities were aided by the fact that the Greek mainland was overpopulated and therefore made the vast Seleucid Empire ripe for colonization. Apart from these cities, there were also a large number of Seleucid garrisons (choria), military colonies (katoikias) and Greek villages (komai) which the Seleucids planted throughout the empire to cement their rule.

Roman Era

Levantine Hellenism flourished under Roman rule in several regions, such as the Decapolis. Antiochians in the Northern Levant found themselves under Roman rule when Seleukeia was eventually annexed by the Roman Republic in 64 BC, by Pompey in the Third Mithridatic War.[11] While those in the Southern Levant were absorbed gradually into the Roman State. Eventually, in 135 AD, after the Bar Kokhba revolt the North and South were merged into the Roman province of Syria Palaestina, which existed until about 390.[12] During its existence, the population of Syria Palaestina in the north consisted of a mixed Polytheistic population of Phoenicians, Arameans and Jews which formed the majority, as well as what remained of Greek colonists, Arab societies of Itureans, and later also the Ghassanids. In the East, Arameans and Assyrians made up the majority. In the South, Samaritans, Nabateans and Greco-Romans made up the majority near the end of the 2nd century.

Byzantine Era

Throughout the Middle Ages, Byzantine Greeks self-identified as Romaioi or Romioi (Greek: Ῥωμαῖοι, Ρωμιοί, meaning "Romans") and Graikoi (Γραικοῖ, meaning "Greeks"). Linguistically, they spoke Byzantine or Medieval Greek, known as "Romaic"[13] which is situated between the Hellenistic (Koine), and modern phases of the language.[14] Byzantines, perceived themselves as the descendants of classical Greece,[15][16][17] the political heirs of imperial Rome,[18][19] and followers of the Apostles.[15] Thus, their sense of "Romanity" was different from that of their contemporaries in the West. "Romaic" was the name of the vulgar Greek language, as opposed to "Hellenic" which was its literary or doctrinal form.[20]

The Byzantine dominion in the Levant known as the Diocese of the East, was one of the major commercial, agricultural, religious, and intellectual areas of the Empire, and its strategic location facing the Sassanid Empire and the unruly desert tribes gave it exceptional military importance.[21] The entire area of the former diocese came under Sassanid occupation between 609 and 628, but it was retaken by the Emperor Heraclius until its irreversible lost to the Arabs after the Battle of Yarmouk and the fall of Antioch.

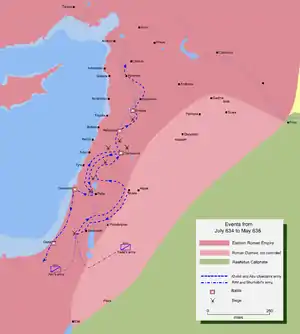

Arab Conquest

Further Information:Muslim conquest of the Levant, Arab-Byzantine Wars

The Arab conquest of Syria (Arabic: الفتح الإسلامي لبلاد الشام) occurred in the first half of the 7th century,[22] and refers to the conquest of the Levant, which later became known as the Islamic Province of Bilad al-Sham. On the eve of the Arab Muslim conquests the Byzantines were still in the process of rebuilding their authority in the Levant, which had been lost to them for almost twenty years.[23] At the time of the Arab conquest, Bilad al-Sham was inhabited mainly by local Aramaic-speaking Christians, Ghassanid and Nabatean Arabs, as well as Greeks, and by non-Christian minorities of Jews, Samaritans, and Itureans. The population of the region did not become predominantly Muslim and Arab in identity until nearly a millennium after the conquest.

In Southern Levant

The Muslim Arab army attacked Jerusalem, held by the Byzantines in November 636. For four months the siege continued. Ultimately, the Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, Sophronius, agreed to surrender Jerusalem to Caliph Umar in person. Umar, then at Medina, agreed to these terms and traveled to Jerusalem to sign the capitulation in the spring of 637. Sophronius of Jerusalem also negotiated a pact with Caliph Umar, known as the Umariyya Covenant or Covenant of Omar, allowing for religious freedom for Christians in exchange for jizya, a tax to be paid to conquered non-Muslims, called "dhimmis".[24] While the majority population of Jerusalem during the time of Arab conquest was Greek - Christian,[25] the majority of Palestine population about 300,000-400,000 inhabitants, was still Jewish.[26] In the aftermath the process of cultural Arabization and Islamization took place, combining immigration to Palestine with the adoption of Arabic language and conversion of the part of local population to Islam.[27]

Ottoman Period

Historically, Followers of the Greek Orthodox Church and Melkite Greek Catholic Church regardless of ethnicity were considered as part of the Rum Millet (millet-i Rûm), or "Roman nation" by the Ottoman authorities.

According to a rare ethnographic study published by French historian and ethnographer Alexander Synvet in 1878. There were 160,000 Greeks living throughout Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine.[28]

Greek War of Independence

As soon as the Greek revolution commenced, Rûm throughout the Empire were targeted for persecutions, and Syria did not escape Ottoman wrath.[29] Fearing that the Rûm of Syria might aid the Greek Revolution, the Porte issued an order that they should be disarmed.[30] In Jerusalem, the city's Greek Christian population, who were estimated to make up around 20% of the city's total,[31] were also forced by the Ottoman authorities to relinquish their weapons, wear black, and help improve the city's fortifications. Greek Orthodox holy sites, such as the Monastery of Our Lady of Balamand, located just south of the city of Tripoli in Lebanon, were subjected to vandalism and revenge attacks, which in fact forced the monks to abandon it until 1830.[32] Not even the Greek Orthodox Patriarch was safe, as orders were received just after the execution of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople to kill the Antiochian Patriarch as well, but local officials failed to execute the orders.

On March 18, 1826, a flotilla of around fifteen Greek ships, led by Vasos Mavrovouniotis attempted to spread the Greek Revolution to the Ottoman Levant. According to then-British Consul John Barker,[33] stationed in Aleppo, in a memo to British Ambassador Stratford Canning, in Constantinople. The Greek Revolutionaries landed in Beirut,[30] but were thwarted by a local mufti and a hastily arranged defense force. Although initially repelled, the Greeks managed to hold on to a small portion of the city near the seashore in an area inhabited by local Rûm during which they appealed to the Rûm "to rise up and join them"[33] and even sent an invitation to the chief of the local Druzes to also join the Revolution. A few days later, on March 23, 1826, regional governor Abdullah Pasha sent his lieutenant and nearly 500 Albanian irregular forces to exacted revenge for the failed uprising.[33]

Aleppo Massacre of 1850

On October 17–18, 1850, Muslim rioters attacked the Christian neighborhoods of Aleppo. In the aftermath, Ottoman records show that 688 homes, 36 shops, and 6 churches were damaged, including the Greek Catholic patriarchate and its library.[34] The events lead hundreds of Christians to emigrate mainly to Beirut and Smyrna.[35]

Damascus Massacre of 1860

On July 10, 1860 Saint Joseph of Damascus and 11,000 Antiochian Greek Orthodox and Catholic Christians[36][37] were killed when Druze marauders destroyed part of the old city of Damascus. The Rûm had taken refuge in the churches and monasteries of Bab Tuma ("Saint Thomas' Gate"). The Massacre was a part of the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war, which began as a Maronite rebellion in Mount Lebanon, and culminated in the massacre in Damascus.

First World War and the Ottoman Greek Genocide

During the First World War, Rûm, alongside Ottoman Greeks, were targeted by the Ittihadist Ottoman authorities in what is now historically known as the Ottoman Greek genocide.[38] As a result, three Antiochian Greek Orthodox Dioceses were completely annihilated; the Metropolis of Tarsus and Adana, the Metropolis of Amida, and the Metropolis of Theodosioupolis. Those Antiochians living outside of the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon were subject to the forced population exchange of 1923, which ended the Ottoman Greek Genocide. One modern Greek town, which is made up of Antiochian survivors from the population exchange is Nea Selefkia, which is located in Epirus. The founders of Nea Selefkia were refugees from Silifke in Cilicia.

Present situation

Damascus has been home to an organized Greek community since 1913, but there are also significant numbers of Greek Muslims originally from Ottoman Crete who have been living in several coastal towns and villages of Syria and Lebanon since the late Ottoman era. They were resettled there by Sultan Abdul Hamid II following the Greco-Turkish War in 1897–98, in which the Ottoman Empire lost Crete to the Kingdom of Greece. The most notable but still understudied Cretan Muslim village in Syria is al-Hamidiyah, many of whose inhabitants continue to speak Greek as their first language. There, of course, is also a significant Greco-Syrian population in Aleppo as well as smaller communities in Latakia, Tartus and Homs.[1]

Greek Muslims in Syria

In addition to the Greek Orthodox Christian population, there are also about 8,000 Greek-speaking Muslims of Cretan origin in Al-Hamidiyah, Syria and 7,000 people of Greek Muslim descent in Tripoli, Lebanon.[39] Greek Muslims constitute a majority of Al-Hamidiyah's population.[39] By 1988, many Greek Muslims from both Lebanon and Syria had reported being subject to discrimination by the Greek embassy because of their religious affiliation. The community members would be regarded with indifference and even hostility and would be denied visas and opportunities to improve their Greek through trips to Greece.[39]

Because of the Syrian Civil War, many Muslim Greeks sought refuge in nearby Cyprus and even some went to their original homeland of Crete, yet they are still considered as foreigners.[40]

See also

References

- Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs Archived 2012-08-19 at the Wayback Machine Relations with Syria

- Herodotus. "Herodotus VII.63". Archived from the original on 1999-02-20. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

VII.63: The Assyrians went to war with helmets upon their heads made of brass, and plaited in a strange fashion which is not easy to describe. They carried shields, lances, and daggers very like the Egyptian; but in addition they had wooden clubs knotted with iron, and linen corselets. This people, whom the Hellenes call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians. The Chaldeans served in their ranks, and they had for commander Otaspes, the son of Artachaeus.

- For Syria, see M. Liverani, "The collapse of the Near Eastern regional system at the end of the Bronze Age: the case of Syria" in Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World, M. Rowlands, M.T. Larsen, K. Kristiansen, eds. (Cambridge University Press) 1987.

- S. Richard, "Archaeological sources for the history of Palestine: The Early Bronze Age: The rise and collapse of urbanism", The Biblical Archaeologist (1987)

- Professor Gerhard Rempel, Hellenistic Civilization (Western New England College) Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ulrich Wilcken, Griechische Geschichte im Rahmen der Altertumsgeschichte.

- Glubb, Sir John Bagot 1967 34

- Steven C. Hause, William S. Maltby (2004). Western civilization: a history of European society. Thomson Wadsworth. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-534-62164-3.

The Greco-Macedonian Elite. The Seleucids respected the cultural and religious sensibilities of their subjects but preferred to rely on Greek or Macedonian soldiers and administrators for the day-to-day business of governing. The Greek population of the cities, reinforced until the second century BCE by immigration from Greece, formed a dominant, although not especially cohesive, elite.

- Victor, Royce M. (2010). Colonial education and class formation in early Judaism: a postcolonial reading. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-567-24719-3.

Like other Hellenistic kings, the Seleucids ruled with the help of their "friends" and a Greco-Macedonian elite class separate from the native populations whom they governed.

- Britannica, "Seleucid kingdom", 2008, O.Ed.

- Sicker, Martin (2001). Between Rome and Jerusalem: 300 years of Roman-Judaean relations By Martin Sicker. ISBN 9780275971403. Archived from the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Lehmann, Clayton Miles (Summer 1998). "Palestine: History: 135–337: Syria Palaestina and the Tetrarchy". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 2009-08-11. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- Adrados 2005, p. 226.

- Alexiou 2001, p. 22.

- Kazhdan & Constable 1982, p. 12; Runciman 1970, p. 14; Niehoff 2012, Margalit Finkelberg, "Canonising and Decanonising Homer: Reception of the Homeric Poems in Antiquity and Modernity", p. 20.

- Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum 2003, p. 482: "As heirs to the Greeks and Romans of old, the Byzantines thought of themselves as Rhomaioi, or Romans, though they knew full well that they were ethnically Greeks." (see also: Savvides & Hendricks 2001)

- Kitzinger 1967, "Introduction", p. x: "All through the Middle Ages the Byzantines considered themselves the guardians and heirs of the Hellenic tradition."

- Kazhdan & Constable 1982, p. 12; Runciman 1970, p. 14; Haldon 1999, p. 7.

- Browning 1992, "Introduction", p. xiii: "The Byzantines did not call themselves Byzantines, but Romaioi—Romans. They were well aware of their role as heirs of the Roman Empire, which for many centuries had united under a single government the whole Mediterranean world and much that was outside it."

- Runciman 1985, p. 119.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. pp. 1533–1534. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- "Syria | History, People, & Maps | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2023-07-14. Archived from the original on 2015-06-16. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- "Britannica Iran"

- Runciman, Steven (1951). A History of the Crusades:The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Penguin Books. Vol.1 pp.3–4. ISBN 0-521-34770-X.

- Luz, Nimrod. "Aspects of Islamization of Space and Society in Mamluk Jerusalem and its Hinterland" (PDF). Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-04. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- Israel Cohen (1950).Contemporary Jewry: a survey of social, cultural, economic, and political conditions, p 310.

- Lauren S. Bahr; Bernard Johnston (M.A.); Louise A. Bloomfield (1996). Collier's encyclopedia: with bibliography and index. Collier's. p. 328. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- "Anemi - Digital Library of Modern Greek Studies - Les Grecs de l'Empire ottoman : Etude statistique et ethnographique / par A. Synvet". anemi.lib.uoc.gr. Archived from the original on 2018-08-16. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- Notes from the life of a Syrian by Antonius Ameuney. A.W. Bennett. 1860. p. 1. Retrieved 4 June 2015 – via Internet Archive.

Greek Revolution Lebanon.

- Priestley, H.I.; American Historical Association (1938). France Overseas: A Study Of Modern Imperialism, 1938. Octagon Books. p. 87. ISBN 9780714610245. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- Fisk and King, 'Description of Jerusalem,' in The Christian Magazine, July 1824, page 220. Mendon Association, 1824.

- Balamand patriarchal monastery. antiochpatriarchate.org. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Bedlam in Beirut: A British Perspective in 1826. University of North Florida. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Eldem, Goffman & Masters 1999, pp. 70

- Commins 2004, pp. 31

- Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977-05-27). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 2, Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808-1975. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29166-8. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- "THE SYRIAN OUTBREAK.; DETAILS OF THE DAMASCUS MASSACRE. FOREIGN INTERVENTION IN SYRIA". The New York Times. 1860-08-13. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- "The Black Book". www.greece.org. Archived from the original on 2020-09-25. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- Greek-Speaking Enclaves of Lebanon and Syria Archived 2022-10-09 at Ghost Archive by Roula Tsokalidou. Proceedings II Simposio Internacional Bilingüismo. Retrieved 18-12-08

- "Europe's forgotten Greek Muslims still suffer 120 years after exile". T-Vine. 24 May 2018. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

Works cited

- Adrados, Francisco Rodriguez (2005). A History of the Greek Language: From its Origins to the Present. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-12835-4. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Alexiou, Margaret (2001). After Antiquity: Greek Language, Myth, and Metaphor. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3301-6. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Browning, Robert (1992). The Byzantine Empire. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-0754-4. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Commins, David Dean (2004). Historical Dictionary of Syria. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4934-1. Archived from the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- Eldem, Edhem; Goffman, Daniel; Masters, Bruce (11 November 1999). The Ottoman City between East and West: Aleppo, Izmir, and Istanbul. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64304-7. Archived from the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- Haldon, John (1999). Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World, 565–1204. London: UCL Press. ISBN 1-85728-495-X.

- Kazhdan, Alexander Petrovich; Constable, Giles (1982). People and Power in Byzantium: An Introduction to Modern Byzantine Studies. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-103-2. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Kitzinger, Ernst (1967). Handbook of the Byzantine Collection. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-025-7. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Niehoff, Maren R. (2012). Homer and the Bible in the Eyes of Ancient Interpreters. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9-00-422134-5. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum (2003). Orientalia Christiana Periodica, Volume 69. Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Runciman, Steven (1970). The Last Byzantine Renaissance. London and New York: Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Runciman, Steven (1985). The Great Church in Captivity: A Study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the Eve of the Turkish Conquest to the Greek War of Independence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31310-0. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Savvides, Alexios G. C.; Hendricks, Benjamin (2001). Introducing Byzantine History (A Manual for Beginners). Paris: University Hêrodotos. ISBN 978-2-911859-13-7. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-05-12.