Synthetic fuel

Synthetic fuel or synfuel is a liquid fuel, or sometimes gaseous fuel, obtained from syngas, a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, in which the syngas was derived from gasification of solid feedstocks such as coal or biomass or by reforming of natural gas.

Common ways for refining synthetic fuels include the Fischer–Tropsch conversion,[1][2] methanol to gasoline conversion,[3] or direct coal liquefaction.[4]

Classification and principles

The term 'synthetic fuel' or 'synfuel' has several different meanings and it may include different types of fuels. More traditional definitions define 'synthetic fuel' or 'synfuel' as a hydrocarbon produced by a sequence of chemical reactions to synthesize the fuel from a feedstock, typically from coal or natural gas, rather by selecting the hydrocarbon by distillation from crude oil. In its Annual Energy Outlook 2006, the Energy Information Administration defines synthetic fuels as fuels produced from coal, natural gas, or biomass feedstocks through chemical conversion into synthetic crude and/or synthetic liquid products.[5] A number of synthetic fuel's definitions include fuels produced from biomass, and industrial and municipal waste.[6][7][8] These definitions also allow oil sands and oil shale to be understood as synthetic fuel sources. In addition to liquid fuels, synthesized gaseous fuels are also considered to be synthetic fuels.[9][10] In his 'Synthetic Fuels Handbook' petrochemist James G. Speight included liquid and gaseous fuels as well as clean solid fuels produced by conversion of coal, oil shale or tar sands, and various forms of biomass, although he admits that in the context of substitutes for petroleum-based fuels it has even wider meaning.[10] Depending on the context, methanol, ethanol and hydrogen may also be included in this category.[11][12]

Synthetic fuels are produced by the chemical process of conversion.[10] Conversion methods could be direct conversion into liquid transportation fuels, or indirect conversion, in which the source substance is converted initially into syngas which then goes through additional conversion process to become liquid fuels.[5] Basic conversion methods include carbonization and pyrolysis, hydrogenation, and thermal dissolution.[13]

History

The process of direct conversion of coal to synthetic fuel originally developed in Germany.[14] Friedrich Bergius developed the Bergius process, which received a patent in 1913. Karl Goldschmidt invited Bergius to build an industrial plant at his factory, the Th. Goldschmidt AG (part of Evonik Industries from 2007), in 1914.[15] Production began in 1919.[16]

Indirect coal conversion (where coal is gasified and then converted to synthetic fuels) was also developed in Germany - by Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch in 1923.[14] During World War II (1939-1945), Germany used synthetic-oil manufacturing (German: Kohleverflüssigung) to produce substitute (Ersatz) oil products by using the Bergius process (from coal), the Fischer–Tropsch process (water gas), and other methods (Zeitz used the TTH and MTH processes).[17][18] In 1931 the British Department of Scientific and Industrial Research located in Greenwich, England, set up a small facility where hydrogen gas was combined with coal at extremely high pressures to make a synthetic fuel.[19]

The Bergius process plants became Nazi Germany's primary source of high-grade aviation gasoline, synthetic oil, synthetic rubber, synthetic methanol, synthetic ammonia, and nitric acid. Nearly one third of the Bergius production came from plants in Pölitz (Polish: Police) and Leuna, with 1/3 more in five other plants (Ludwigshafen had a much smaller Bergius plant[20] which improved "gasoline quality by dehydrogenation" using the DHD process).[18]

Synthetic fuel grades included "T.L. [jet] fuel", "first quality aviation gasoline", "aviation base gasoline", and "gasoline - middle oil";[18] and "producer gas" and diesel were synthesized for fuel as well (converted armored tanks, for example, used producer gas).[17]: 4, s2 By early 1944 German synthetic-fuel production had reached more than 124,000 barrels per day (19,700 m3/d) from 25 plants,[21] including 10 in the Ruhr Area.[22]: 239 In 1937 the four central Germany lignite coal plants at Böhlen, Leuna, Magdeburg/Rothensee, and Zeitz, along with the Ruhr Area bituminous coal plant at Scholven/Buer, produced 4.8 million barrels (760×103 m3) of fuel. Four new hydrogenation plants (German: Hydrierwerke) were subsequently erected at Bottrop-Welheim (which used "Bituminous coal tar pitch"),[18] Gelsenkirchen (Nordstern), Pölitz, and, at 200,000 tons/yr[18] Wesseling.[23] Nordstern and Pölitz/Stettin used bituminous coal, as did the new Blechhammer plants.[18] Heydebreck synthesized food oil, which was tested on concentration camp prisoners.[24] After Allied bombing of Germany's synthetic-fuel production plants (especially in May to June 1944), the Geilenberg Special Staff used 350,000 mostly foreign forced-laborers to reconstruct the bombed synthetic-oil plants,[22]: 210, 224 and, in an emergency decentralization program, the Mineralölsicherungsplan (1944-1945), to build 7 underground hydrogenation plants with bombing protection (none were completed). (Planners had rejected an earlier such proposal, expecting that Axis forces would win the war before the bunkers would be completed.)[20] In July 1944 the "Cuckoo" project underground synthetic-oil plant (800,000 m2) was being "carved out of the Himmelsburg" north of the Mittelwerk, but the plant remained unfinished at the end of World War II.[17] Production of synthetic fuel became even more vital for Nazi Germany when Soviet Red Army forces occupied the Ploiești oilfields in Romania on 24 August 1944, denying Germany access to its most important natural oil source.

Indirect Fischer–Tropsch ("FT") technologies were brought to the United States after World War II, and a 7,000 barrels per day (1,100 m3/d) plant was designed by HRI and built in Brownsville, Texas. The plant represented the first commercial use of high-temperature Fischer–Tropsch conversion. It operated from 1950 to 1955, when it was shut down after the price of oil dropped due to enhanced production and huge discoveries in the Middle East.[14]

In 1949 the U.S. Bureau of Mines built and operated a demonstration plant for converting coal to gasoline in Louisiana, Missouri.[25] Direct coal conversion plants were also developed in the US after World War II, including a 3 TPD plant in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, and a 250-600 TPD Plant in Catlettsburg, Kentucky.[26]

In later decades the Republic of South Africa established a state oil company including a large synthetic fuel establishment.

Processes

The numerous processes that can be used to produce synthetic fuels broadly fall into three categories: Indirect, Direct, and Biofuel processes.

Indirect conversion

Indirect conversion has the widest deployment worldwide, with global production totaling around 260,000 barrels per day (41,000 m3/d), and many additional projects under active development.

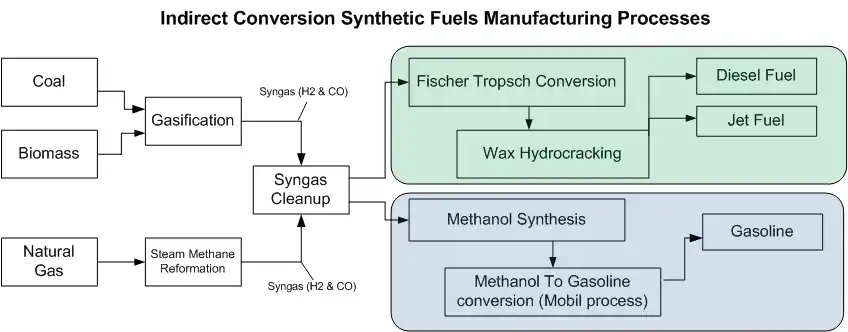

Indirect conversion broadly refers to a process in which biomass, coal, or natural gas is converted to a mix of hydrogen and carbon monoxide known as syngas either through gasification or steam methane reforming, and that syngas is processed into a liquid transportation fuel using one of a number of different conversion techniques depending on the desired end product.[27]

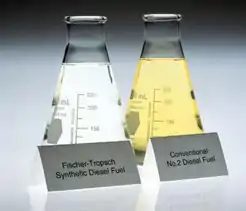

The primary technologies that produce synthetic fuel from syngas are Fischer–Tropsch synthesis and the Mobil process (also known as Methanol-To-Gasoline, or MTG). In the Fischer–Tropsch process syngas reacts in the presence of a catalyst, transforming into liquid products (primarily diesel fuel and jet fuel) and potentially waxes (depending on the FT process employed).[28]

The process of producing synfuels through indirect conversion is often referred to as coal-to-liquids (CTL), gas-to-liquids (GTL) or biomass-to-liquids (BTL), depending on the initial feedstock. At least three projects (Ohio River Clean Fuels, Illinois Clean Fuels, and Rentech Natchez) are combining coal and biomass feedstocks, creating hybrid-feedstock synthetic fuels known as Coal and Biomass To Liquids (CBTL).[29]

Indirect conversion process technologies can also be used to produce hydrogen, potentially for use in fuel cell vehicles, either as slipstream co-product, or as a primary output.[30]

Direct conversion

Direct conversion refers to processes in which coal or biomass feedstocks are converted directly into intermediate or final products, avoiding the conversion to syngas via gasification. Direct conversion processes can be broadly broken up into two different methods: Pyrolysis and carbonization, and hydrogenation.[31]

Hydrogenation processes

One of the main methods of direct conversion of coal to liquids by hydrogenation process is the Bergius process.[32] In this process, coal is liquefied by heating in the presence of hydrogen gas (hydrogenation). Dry coal is mixed with heavy oil recycled from the process. Catalysts are typically added to the mixture. The reaction occurs at between 400 °C (752 °F) to 500 °C (932 °F) and 20 to 70 MPa hydrogen pressure.[33] The reaction can be summarized as follows:[33]

After World War I several plants were built in Germany; these plants were extensively used during World War II to supply Germany with fuel and lubricants.[34]

The Kohleoel Process, developed in Germany by Ruhrkohle and VEBA, was used in the demonstration plant with the capacity of 200 ton of lignite per day, built in Bottrop, Germany. This plant operated from 1981 to 1987. In this process, coal is mixed with a recycle solvent and iron catalyst. After preheating and pressurizing, H2 is added. The process takes place in tubular reactor at the pressure of 300 bar and at the temperature of 470 °C (880 °F).[35] This process was also explored by SASOL in South Africa.

In 1970-1980s, Japanese companies Nippon Kokan, Sumitomo Metal Industries and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries developed the NEDOL process. In this process, a mixture of coal and recycled solvent is heated in the presence of iron-based catalyst and H2. The reaction takes place in tubular reactor at temperature between 430 °C (810 °F) and 465 °C (870 °F) at the pressure 150-200 bar. The produced oil has low quality and requires intensive upgrading.[35] H-Coal process, developed by Hydrocarbon Research, Inc., in 1963, mixes pulverized coal with recycled liquids, hydrogen and catalyst in the ebullated bed reactor. Advantages of this process are that dissolution and oil upgrading are taking place in the single reactor, products have high H:C ratio, and a fast reaction time, while the main disadvantages are high gas yield, high hydrogen consumption, and limitation of oil usage only as a boiler oil because of impurities.[36]

The SRC-I and SRC-II (Solvent Refined Coal) processes were developed by Gulf Oil and implemented as pilot plants in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s.[35] The Nuclear Utility Services Corporation developed hydrogenation process which was patented by Wilburn C. Schroeder in 1976. The process involved dried, pulverized coal mixed with roughly 1wt% molybdenum catalysts.[10] Hydrogenation occurred by use of high temperature and pressure syngas produced in a separate gasifier. The process ultimately yielded a synthetic crude product, Naphtha, a limited amount of C3/C4 gas, light-medium weight liquids (C5-C10) suitable for use as fuels, small amounts of NH3 and significant amounts of CO2.[37] Other single-stage hydrogenation processes are the Exxon donor solvent process, the Imhausen High-pressure Process, and the Conoco Zinc Chloride Process.[35]

A number of two-stage direct liquefaction processes have been developed. After the 1980s only the Catalytic Two-stage Liquefaction Process, modified from the H-Coal Process; the Liquid Solvent Extraction Process by British Coal; and the Brown Coal Liquefaction Process of Japan have been developed.[35]

Chevron Corporation developed a process invented by Joel W. Rosenthal called the Chevron Coal Liquefaction Process (CCLP). It is unique due to the close-coupling of the non-catalytic dissolver and the catalytic hydroprocessing unit. The oil produced had properties that were unique when compared to other coal oils; it was lighter and had far fewer heteroatom impurities. The process was scaled-up to the 6 ton per day level, but not proven commercially.

Pyrolysis and carbonization processes

There are a number of different carbonization processes. The carbonization conversion occurs through pyrolysis or destructive distillation, and it produces condensable coal tar, oil and water vapor, non-condensable synthetic gas, and a solid residue-char. The condensed coal tar and oil are then further processed by hydrogenation to remove sulfur and nitrogen species, after which they are processed into fuels.[36]

The typical example of carbonization is the Karrick process. The process was invented by Lewis Cass Karrick in the 1920s. The Karrick process is a low-temperature carbonization process, where coal is heated at 680 °F (360 °C) to 1,380 °F (750 °C) in the absence of air. These temperatures optimize the production of coal tars richer in lighter hydrocarbons than normal coal tar. However, the produced liquids are mostly a by-product and the main product is semi-coke, a solid and smokeless fuel.[38]

The COED Process, developed by FMC Corporation, uses a fluidized bed for processing, in combination with increasing temperature, through four stages of pyrolysis. Heat is transferred by hot gases produced by combustion of part of the produced char. A modification of this process, the COGAS Process, involves the addition of gasification of char.[36] The TOSCOAL Process, an analogue to the TOSCO II oil shale retorting process and Lurgi-Ruhrgas process, which is also used for the shale oil extraction, uses hot recycled solids for the heat transfer.[36]

Liquid yields of pyrolysis and Karrick processes are generally low for practical use for synthetic liquid fuel production.[38] Furthermore, the resulting liquids are of low quality and require further treatment before they can be used as motor fuels. In summary, there is little possibility that this process will yield economically viable volumes of liquid fuel.[38]

Biofuels processes

One example of a Biofuel-based synthetic fuel process is Hydrotreated Renewable Jet (HRJ) fuel. There are a number of variants of these processes under development, and the testing and certification process for HRJ aviation fuels is beginning.[39][40]

There are two such process under development by UOP. One using solid biomass feedstocks, and one using bio-oil and fats. The process using solid second-generation biomass sources such as switchgrass or woody biomass uses pyrolysis to produce a bio-oil, which is then catalytically stabilized and deoxygenated to produce a jet-range fuel. The process using natural oils and fats goes through a deoxygenation process, followed by hydrocracking and isomerization to produce a renewable Synthetic Paraffinic Kerosene jet fuel.[41]

Oil sand and oil shale processes

Synthetic crude may also be created by upgrading bitumen (a tar like substance found in oil sands), or synthesizing liquid hydrocarbons from oil shale. There are a number of processes extracting shale oil (synthetic crude oil) from oil shale by pyrolysis, hydrogenation, or thermal dissolution.[13][42]

Commercialization

Worldwide commercial synthetic fuels plant capacity is over 240,000 barrels per day (38,000 m3/d), including indirect conversion Fischer–Tropsch plants in South Africa (Mossgas, Secunda CTL), Qatar {Oryx GTL}, and Malaysia (Shell Bintulu), and a Mobil process (Methanol to Gasoline) plant in New Zealand.[5][43] Synthetic fuel plant capacity is approximately 0.24% of the 100 million barrel per day crude oil refining capacity worldwide.[44]

Sasol, a company based in South Africa operates the world's only commercial Fischer–Tropsch coal-to-liquids facility at Secunda, with a capacity of 150,000 barrels per day (24,000 m3/d).[45] British company Zero, co-founded by former F1 technical director Paddy Lowe, has developed a solution it terms 'petrosynthesis' to develop synthetic fuels and in 2022 it began work on a demonstration production plant[46] at Bicester Heritage near Oxford.

Economics

The economics of synthetic fuel manufacture vary greatly depending the feedstock used, the precise process employed, site characteristics such as feedstock and transportation costs, and the cost of additional equipment required to control emissions. The examples described below indicate a wide range of production costs between $20/BBL for large-scale gas-to-liquids, to as much as $240/BBL for small-scale biomass-to-liquids and carbon capture and sequestration.[29]

In order to be economically viable, projects must do much better than just being competitive head-to-head with oil. They must also generate a sufficient return on investment to justify the capital investment in the project.[29]

Security considerations

A central consideration for the development of synthetic fuel is the security factor of securing domestic fuel supply from domestic biomass and coal. Nations that are rich in biomass and coal can use synthetic fuel to offset their use of petroleum derived fuels and foreign oil.[47]

Environmental considerations

The environmental footprint of a given synthetic fuel varies greatly depending on which process is employed, what feedstock is used, what pollution controls are employed, and what the transportation distance and method are for both feedstock procurement and end-product distribution.[29]

In many locations, project development will not be possible due to permitting restrictions if a process design is chosen that does not meet local requirements for clean air, water, and increasingly, lifecycle carbon emissions.[48][49]

Lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions

Among different indirect FT synthetic fuels production technologies, potential emissions of greenhouse gases vary greatly. Coal to liquids ("CTL") without carbon capture and sequestration ("CCS") is expected to result in a significantly higher carbon footprint than conventional petroleum-derived fuels (+147%).[29] On the other hand, biomass-to-liquids with CCS could deliver a 358% reduction in lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions.[29] Both of these plants fundamentally use gasification and FT conversion synthetic fuels technology, but they deliver wildly divergent environmental footprints.

Generally, CTL without CCS has a higher greenhouse gas footprint. CTL with CCS has a 9-15% reduction in lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions compared to that of petroleum derived diesel.[29][50]

CBTL+CCS plants that blend biomass alongside coal while sequestering carbon do progressively better the more biomass is added. Depending on the type of biomass, the assumptions about root storage, and the transportation logistics, at conservatively 40% biomass alongside coal, CBTL+CCS plants achieve a neutral lifecycle greenhouse gas footprint. At more than 40% biomass, they begin to go lifecycle negative, and effectively store carbon in the ground for every gallon of fuels that they produce.[29]

Ultimately BTL plants employing CCS could store massive amounts of carbon while producing transportation fuels from sustainably produced biomass feedstocks, although there are a number of significant economic hurdles, and a few technical hurdles that would have to be overcome to enable the development of such facilities.[29]

Serious consideration must also be given to the type and method of feedstock procurement for either the coal or biomass used in such facilities, as reckless development could exacerbate environmental problems caused by mountaintop removal mining, land use change, fertilizer runoff, food vs. fuels concerns, or many other potential factors. Or they could not, depending entirely on project-specific factors on a plant-by-plant basis.

A study from U.S. Department of Energy National Energy Technology Laboratory with much more in-depth information of CBTL life-cycle emissions "Affordable Low Carbon Diesel from Domestic Coal and Biomass".[29]

Hybrid hydrogen-carbon processes have also been proposed recently[51] as another closed-carbon cycle alternative, combining 'clean' electricity, recycled CO, H2 and captured CO2 with biomass as inputs as a way of reducing the biomass needed.

Fuels emissions

The fuels produced by the various synthetic fuels process also have a wide range of potential environmental performance, though they tend to be very uniform based on the type of synthetic fuels process used (i.e. the tailpipe emissions characteristics of Fischer–Tropsch diesel tend to be the same, though their lifecycle greenhouse gas footprint can vary substantially based on which plant produced the fuel, depending on feedstock and plant level sequestration considerations.)

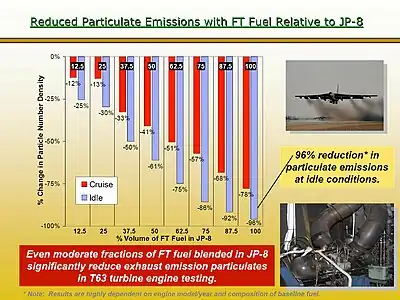

In particular, Fischer–Tropsch diesel and jet fuels deliver dramatic across-the-board reductions in all major criteria pollutants such as SOx, NOx, Particulate Matter, and Hydrocarbon emissions.[52] These fuels, because of their high level of purity and lack of contaminants, allow the use of advanced emissions control equipment. In a 2005 dynamometer study simulating urban driving the combination was shown to virtually eliminate HC, CO, and PM emissions from diesel trucks with a 10% increase in fuel consumption using a Shell gas to liquid fuel fitted with a combination particulate filter and catalytic converter compared to the same trucks unmodified using California Air Resource Board diesel fuel .[53]

In testimony before the Subcommittee on Energy and Environment of the U.S. House of Representatives the following statement was made by a senior scientist from Rentech:

F-T fuels offer numerous benefits to aviation users. The first is an immediate reduction in particulate emissions. F-T jet fuel has been shown in laboratory combusters and engines to reduce PM emissions by 96% at idle and 78% under cruise operation. Validation of the reduction in other turbine engine emissions is still under way. Concurrent to the PM reductions is an immediate reduction in CO2 emissions from F-T fuel. F-T fuels inherently reduce CO2 emissions because they have higher energy content per carbon content of the fuel, and the fuel is less dense than conventional jet fuel allowing aircraft to fly further on the same load of fuel.[54]

The "cleanness" of these FT synthetic fuels is further demonstrated by the fact that they are sufficiently non-toxic and environmentally benign as to be considered biodegradable. This owes primarily to the near-absence of sulfur and extremely low level of aromatics present in the fuel.[55]

Using Fischer–Tropsch jet fuels have been proven to dramatically reduce particulate and other aircraft emissions.

Using Fischer–Tropsch jet fuels have been proven to dramatically reduce particulate and other aircraft emissions.

Sustainability

One concern commonly raised about the development of synthetic fuels plants is sustainability. Fundamentally, transitioning from oil to coal or natural gas for transportation fuels production is a transition from one inherently depletable geologically limited resource to another.

One of the positive defining characteristics of synthetic fuels production is the ability to use multiple feedstocks (coal, gas, or biomass) to produce the same product from the same plant. In the case of hybrid BCTL plants, some facilities are already planning to use a significant biomass component alongside coal. Ultimately, given the right location with good biomass availability, and sufficiently high oil prices, synthetic fuels plants can be transitioned from coal or gas, over to a 100% biomass feedstock. This provides a path forward towards a renewable fuel source and possibly more sustainable, even if the plant originally produced fuels solely from coal, making the infrastructure forwards-compatible even if the original fossil feedstock runs out.

Some synthetic fuels processes can be converted to sustainable production practices more easily than others, depending on the process equipment selected. This is an important design consideration as these facilities are planned and implemented, as additional room must be left in the plant layout to accommodate whatever future plant change requirements in terms of materials handling and gasification might be necessary to accommodate a future change in production profile.

For vehicles with Internal Combustion Engines

Electrofuels, also known as e-fuels or synthetic fuels, are a type of drop-in replacement fuel. They are manufactured using captured carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide, together with hydrogen obtained from sustainable electricity sources such as wind, solar and nuclear power.[56]

The process uses carbon dioxide in manufacturing and releases around the same amount of carbon dioxide into the air when the fuel is burned, for an overall low carbon footprint. Electrofuels are thus an option for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transport, particularly for long-distance freight, marine, and air transport.[57]

The primary targets are butanol, and biodiesel, but include other alcohols and carbon-containing gases such as methane and butane.

See also

References

- "Liquid Fuels - Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis". Gasifipedia. National Energy Technology Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- J. Loosdrecht, Van De; Botes, F. G.; Ciobica, I. M.; Ferreira, A. C.; Gibson, P.; Moodley, D. J.; Saib, A. M.; Visagie, J. L.; Weststrate, C. J.; Niemantsverdriet, J. W. (2013). "Fischer-Tropsch synthesis: catalysts and chemistry". Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry II: From Elements to Applications. Surface Inorganic Chemistry and Heterogeneous Catalysis: 525–557. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097774-4.00729-4. ISBN 9780080965291.

- "Liquid Fuels - Conversion of Methanol to Gasoline". Gasifipedia. National Energy Technology Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "Liquid Fuels - Direct Liquefaction Processes". Gasifipedia. National Energy Technology Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- Annual Energy Outlook 2006 with Projections to 2030 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Energy Information Administration. 2006. pp. 52–54. DOE/EIA-0383(2006). Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- Patel, Prachi (2007-12-21). "A comparison of coal and biomass as feedstocks for synthetic fuel production". In Veziroǧlu, T. N. (ed.). Alternative energy sources: an international compendium. MIT Technology Review.

- Antal, M. J. (1978). "Fuel from waste. A portable system converts biowaste into jet fuel and diesel for the military". Hemisphere. p. 3203. ISBN 978-0-89116-085-4.

- Thipse, S. S.; Sheng, C.; Booty, M. R.; Magee, R. S.; Dreizin, E. L. (2001). "Synthetic fuel for imitation of municipal solid waste in experimental studies of waste incineration". Chemosphere. Elsevier. 44 (5): 1071–1077. Bibcode:2001Chmsp..44.1071T. doi:10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00470-7. PMID 11513393.

- Lee, Sunggyu; Speight, James G.; Loyalka, Sudarshan K. (2007). Handbook of Alternative Fuel Technologies. CRC Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-8247-4069-6. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- Speight, James G. (2008). Synthetic Fuels Handbook: Properties, Process, and Performance. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 1–2, 9–10. ISBN 978-0-07-149023-8. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- Lee, Sunggyu (1990). Methanol Synthesis Technology. CRC Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8493-4610-1. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- Lapedes, Daniel N. (1976). McGraw-Hill encyclopedia of energy. McGraw-Hill. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-07-045261-9.

- Luik, Hans (2009-06-08). Alternative technologies for oil shale liquefaction and upgrading (PDF). International Oil Shale Symposium. Tallinn, Estonia: Tallinn University of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- Cicero, Daniel (2007-06-11). Coal Gasification & Co-production of Chemicals & Fuels (PDF). Workshop on Gasification Technologies. Indianapolis. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- According to the Degussa biography of Hans Goldschmidt at "Degussa Geschichte - Hans Goldschmidt". Retrieved 2009-11-10., Karl Goldschmidt had invited Bergius to become director of research at Chemische Fabrik Th. Goldschmidt.

- "caer.uky.edu" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-16. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- "Minutes of Meeting No. 45/6" (PDF). Enemy Oil Intelligence Committee. 1945-02-06. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-21. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- Schroeder, W. C. (August 1946). Holroyd, R. (ed.). "Report On Investigations by Fuels and Lubricants Teams At The I.G. Farbenindustrie, A. G., Works, Ludwigshafen and Oppau". United States Bureau of Mines, Office of Synthetic Liquid Fuels. Archived from the original on 2007-11-08. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- Corporation, Bonnier (1 October 1931). "Popular Science". Bonnier Corporation – via Google Books.

- Miller, Donald L. (2006). Masters of the Air: America's Bomber Boys Who Fought the Air War Against Nazi Germany. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 314, 461. ISBN 978-0-7432-3544-0.

- "The Early Days of Coal Research". Fossil Energy. United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- Galland, Adolf (1968) [1954]. The First and the Last: The Rise and Fall of the German Fighter Forces, 1938-1945 (Ninth Printing - paperbound). New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 210, 224, 239.

- Becker, Peter W. (1981). "The Role of Synthetic Fuel In World War II Germany: implications for today?". Air University Review. Maxwell AFB. Archived from the original on 2013-02-22. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- Speer, Albert (1970). Inside the Third Reich. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. New York and Toronto: Macmillan. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-684-82949-4. LCCN 70119132. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- Corporation, Bonnier (September 13, 1949). "Popular Science". Bonnier Corporation – via Google Books.

- "COAL–TO–LIQUIDS an alternative oil supply?" (PDF). International Energy Agency. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- "10.5. Indirect Liquefaction Processes". netl.doe.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- "10.2. Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis". netl.doe.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- Tarka, Thomas J.; Wimer, John G.; Balash, Peter C.; Skone, Timothy J.; Kern, Kenneth C.; Vargas, Maria C.; Morreale, Bryan D.; White III, Charles W.; Gray, David (2009). "Affordable Low Carbon Diesel from Domestic Coal and Biomass" (PDF). United States Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory. pp. 1, 30.

- Edward Schmetz & Lowell Miller (2005). "Hydrogen Production from Coal, 2005 Annual DOE Hydrogen Program Review". U.S. Department of Energy Office of Sequestration, Hydrogen, and Clean Coal Fuels. p. 4.

- "10.6. Direct Liquefaction Processes". netl.doe.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- Robert Haul: Friedrich Bergius (1884-1949), p. 62 in 'Chemie in unserer Zeit', VCH-Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 19. Jahrgang, April 1985, Weinheim Germany

- James G. Speight (24 December 2010). Handbook of Industrial Hydrocarbon Processes. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-08-094271-1. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Stranges, Anthony N. (1984). "Friedrich Bergius and the Rise of the German Synthetic Fuel Industry". Isis. University of Chicago Press. 75 (4): 643–667. doi:10.1086/353647. JSTOR 232411. S2CID 143962648.

- Cleaner Coal Technology Programme (October 1999). "Technology Status Report 010: Coal Liquefaction" (PDF). Department of Trade and Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-04. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- Lee, Sunggyu (1996). Alternative fuels. CRC Press. pp. 166–198. ISBN 978-1-56032-361-7. Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- Lowe, Phillip A.; Schroeder, Wilburn C.; Liccardi, Anthony L. (1976). "Technical Economies, Synfuels and Coal Energy Symposium, Solid-Phase Catalytic Coal Liquefaction Process". American Society of Mechanical Engineers. p. 35.

- Höök, Mikael; Aleklett, Kjell (2009). "A review on coal to liquid fuels and its coal consumption" (PDF). International Journal of Energy Research. Wiley InterScience. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- "JetBlue readies for alternative fuel trial". Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- "USAF launches new biofuel testing programme". Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- "UOP Receives $1.5M for Pyrolysis Oil Project from DOE". Green Car Congress. 2008-10-29. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- Burnham, Alan K.; McConaghy, James R. (2006-10-16). Comparison of the acceptability of various oil shale processes (PDF). 26th Oil shale symposium. Golden, Colorado: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. UCRL-CONF-226717. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- Motor-fuel production at the New Zealand Synfuel site has been shut down since the mid nineties, although production of methanol for export continues. This site ran on the Mobil process converting gas to methanol and methanol to gasoline.http://www.techhistory.co.nz/ThinkBig/Petrochemical%20Decisions.htm

- "Topic: Oil refinery industry worldwide". Statista. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- "Sasol Inzalo -" (PDF). www.sasol.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-07. Retrieved 2006-10-12.

- Calderwood, Dave (2022-10-05). "Zero Petroleum to produce synthetic fuels at Bicester". FLYER. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- "CTLC Synthetic Fuel Will Enhance U.S. National Security" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- examples of such restrictions include the US Clean Air Act and clean air mercury rule Archived August 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, and the recent limits imposed on new coal-to-liquids projects in China by the National Development and Reform Commission

- An excessive carbon footprint can prevent the United States federal government from being able to purchase fuel. Section 526 of the Energy Independence And Security Act prohibits Federal agencies, including the Department of Defense, from purchasing alternative synfuels unless the alternative fuels have lower GHG emissions than refined petroleum based fuels. Kosich, Dorothy (2008-04-11). "Repeal sought for ban on U.S. Govt. use of CTL, oil shale, tar sands-generated fuel". Mine Web. Archived from the original on 2016-05-16. Retrieved 2008-05-27. Bloom David I; Waldron Roger; Layton Duane W; Patrick Roger W (2008-03-04). "United States: Energy Independence And Security Act Provision Poses Major Problems For Synthetic And Alternative Fuels". Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- "Coal-To-Liquid Fuels Have Lower GHG Than Some Refined Fuels". Archived from the original on 2009-12-14. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- Agrawal R; Singh NR; Ribeiro FH; Delgass WN (2007). "Sustainable fuel for the transportation sector". PNAS. 104 (12): 4828–4833. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.4828A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609921104. PMC 1821126. PMID 17360377.

- Per the work of NREL "Fuel Property, Emission Test, and Operability Results from a Fleet of Class 6 Vehicles Operating on Gas-To-Liquid Fuel and Catalyzed Diesel Particle Filters" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-08. Retrieved 2010-02-13., "Yosemite Waters Vehicle Evaluation Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-08. Retrieved 2009-04-13., and various other DOE/DOD studies

- see Yosemite Waters study "Yosemite Waters Vehicle Evaluation Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-08. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- "Technical Support Document, Coal-to-Liquids Products Industry Overview, Proposed Rule for Mandatory Reporting of Greenhouse Gases" (.PDF). Office of Air and Radiation, United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2009-01-28. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- "Biodegradable diesel fuel". Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- Royal Society 2019, p. 7.

- Royal Society 2019, pp. 9–13.

- Synfuel Plants Expand In W. Va (Coal Age, Feb 1, 2002)

External links

- Alliance for Synthetic Fuels in Europe

- Gas to liquids technology worldwide, ACTED Consultants Archived 2017-02-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Gasifipedia - Liquid Fuels Archived 2017-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Synfuel Producers Hit Paydirt! Archived 2005-09-03 at the Wayback Machine (NCPA Policy Digest) - an analysis of synfuel subsidies in the USA

- US DoD launches quest for energy self-sufficiency Jane's Defence Weekly, 25 September 2006

- Alberta Oil Sands Discovery Centre

- Bitumen and Synthetic Crude Oil

- EU project to convert CO2 to liquid fuels Archived 2008-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Fourth generation synthetic fuels using synthetic life. TED talk by Craig Venter