Sweethearts (play)

Sweethearts is a comic play billed as a "dramatic contrast" in two acts by W. S. Gilbert. The play tells a sentimental and ironic story of the differing recollections of a man and a woman about their last meeting together before being separated and reunited after 30 years.

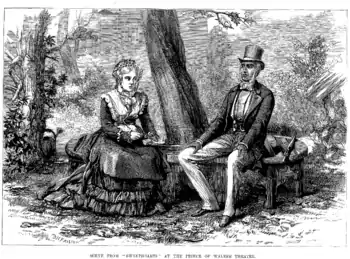

It was first produced on 7 November 1874 at the Prince of Wales's Theatre in London, running for 132 performances until 13 April 1875. It enjoyed many revivals, thereafter, into the 1920s. The first professional production of Sweethearts in Britain in recent memory was given in 2007 at the Finborough Theatre in London, along with Arthur Sullivan's The Zoo.[1]

Background

This romantic comedy of manners was written for Squire Bancroft and his wife Marie (née Wilton), managers of the Prince of Wales's Theatre, and starred Mrs. Bancroft. Gilbert wanted his friend John Hare to play the male lead, to take advantage of Hare's naturally boyish appearance and of his talent for impersonating elderly men, contrasting the character in youth in the first act and old age in the second. In rehearsal, however, Hare struggled with playing the young romantic lead, and the Bancrofts were not satisfied with him, and so another company member, Charles Coghlan, played the role.[2] The Bancrofts had produced the best plays of Tom Robertson in the 1860s, and Sweethearts was Gilbert's tribute to Robertson's "realist" style. The importance of small incidents is emphasised, characters are revealed through "small talk," and what is left unsaid in the script are as important to the play as what is said in the dialogue. These are all Robertson trademarks, though they are not key features of Gilbert's other plays. However, the play combines sentiment with a typically Gilbertian sense of irony. The story of the play deals with themes such as the differences between men's and women's recollections of romantic episodes, and the spread of housing developments to greenfield land.

The initial production of the play ran for 132 performances until 13 April 1875.[3] The Times was much impressed with Mrs. Bancroft and the little play, commenting, "the subtlest of mental conflicts and the most delicate nuances of emotion are expressed in graceful dialogue.... That the piece is thoroughly successful, and that it will be much talked about as one of the theatrical curiosities of the day, there can be no doubt".[4] Coghlan received generally good notices, though one critic commented that he "could not fail to suggest to playgoers what a star the management has lost in Mr. Hare".[5] Squire Bancroft called Sweethearts "one of the most charming and successful plays we ever produced." Thereafter, it enjoyed many revivals and was toured extensively by the Bancrofts and the Kendals.[2] The play continued to be produced until at least the 1920s.[6]

Early in his career, Gilbert experimented with his dramatic style. After a number of broad comedies, farces and burlesques, he wrote a series of short comic operas for the German-Reeds at the Gallery of Illustration. At the same time, he created several 'fairy comedies' at the Haymarket Theatre, including The Palace of Truth (1870) and Pygmalion and Galatea (1871).[7] These works, as well as another series of plays that included The Wicked World (1873), Sweethearts, Charity (1874), and Broken Hearts (1875), established that Gilbert's capabilities extended far beyond burlesque, won him artistic credentials, and demonstrated that he was a writer of wide range, as comfortable with human drama as with farcical humour.[2] The success of these plays gave Gilbert a prestige that would be crucial to his later collaboration with as respected a musician as Sullivan.

1874 was a busy year for Gilbert. He illustrated The Piccadilly Annual; supervised a revival of Pygmalion and Galatea; and, besides Sweethearts, he wrote Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, a parody of Hamlet; Charity, a play about the redemption of a fallen woman; a dramatisation of Ought We to Visit Her? (a novel by Annie Edwardes), an adaptation from the French, Committed for Trial, another adaptation from the French called The Blue-Legged Lady, and Topsyturveydom, a comic opera. He also wrote a Bab-illustrated story called "The Story of a Twelfth Cake" for the Graphic Christmas number.

A drawing room ballad of the same name was created in 1875 to help advertise the play, based on the story-line of the play, with music by the composer who would go on to become Gilbert's most famous collaborator, Arthur Sullivan. It is one of only three Gilbert and Sullivan songs that were not part of a larger work.

Roles and original cast

- Mr. Henry Spreadbrow (Age 21 in Act I; Age 51 in Act II) – Charles Coughlan

- Wilcox, a Gardener – Mr. F. Glover

- Miss Jane Northcott (Age 18 in Act I; Age 48 in Act II) – Marie Wilton (Mrs. Bancroft)

- Ruth, a Maidservant – Miss Plowden

- Note: in Britain, Harry is often an affectionate name for Henry, and Jenny is an affectionate name for Jane.

Synopsis

Act I – 1844

A stiff Victorian youth, "Harry" Spreadbrow, has been suddenly called away to India and must leave immediately. He visits his childhood friend, a delicate if spirited young woman, "Jenny" Northcott, who is busy in her garden. He has long loved her. Harry summons the courage to declare his love and propose marriage to her, but Jenny is flirtatious and capricious, and frustrates his every overture, letting him believe that she does not care for him. He asks her to plant a sapling near the window that would remind her of him, and they plant it together, despite her protest that it would eventually block the view. He also asks her to give him a flower to remember her by, and he gives her a flower in return, which she puts to one side without seeming to care about it. At last, dejected, he leaves, but then she bursts into tears.

Act II – 1874

30 years later, Jane, still single, lives in the same house with her nephew, though the garden has grown much in thirty years. Harry, now Sir Henry Spreadbrow, also single, returns; he has just retired from his career and returned from India. When they meet again, the full nature of the irony reveals itself: Jane has remained faithful to him all those years and remembers their last meeting in every detail. But Henry had recovered from his passion for her within the month and has forgotten most of the details of their meeting. The sapling that they had planted together has grown into a large tree, and Henry is astonished that Jane would have such a big tree blocking the view. Jane has kept the flower he gave her, while Henry had long ago lost the flower she gave him. "How like a woman!" says Sir Henry, to throw aside the flower and then keep it for thirty years; "How like a man!" Jane retorts, to swear undying love and then forget almost immediately. Henry makes it clear, however, that their romance is only just beginning.

Notes

- "About: Sweethearts & The Zoo – A 'Gilbert and Sullivan' Doublebill", OffWestEnd.com, 2007

- Stedman, chapter 8

- Moss, Simon. "Sweethearts" at Gilbert & Sullivan: a selling exhibition of memorabilia, c20th.com, retrieved 16 November 2009

- "Prince of Wales's Theatre", The Times, 9 November 1874

- "The Prince of Wales's", The Penny Illustrated Paper and Illustrated Times, 14 November 1874, p. 315

- Crowther, Andrew (24 May 1998). ""Sweethearts" by W. S. Gilbert". The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- "Miss Anderson as Galatea", The New-York Times, 1883 January 23 32(9791): 5, col. 3 Amusements, retrieved 15 October 2006.

References

- Goldberg, Isaac, The Story of Gilbert and Sullivan (1929)

- Sweethearts libretto and plot summary at the Gilbert and Sullivan archive

- Crowther, Andrew (2000). Contradiction Contradicted – The Plays of W. S. Gilbert. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3839-2.

- Stedman, Jane W. (1996). W. S. Gilbert, A Classic Victorian & His Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816174-3.