Swamping argument

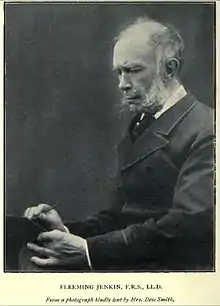

The swamping argument is an objection against Darwinism made by Fleeming Jenkin. He asserted that an accidentally-appearing profitable variety cannot be preserved by natural selection in the population, but should be 'swamped' with ordinary traits. Population genetics helped to overcome this logical difficulty.

Jenkin’s article was published anonymously in the North British Review in June 1867. It took Darwin a year and a half to discover that the author was Fleeming Jenkin, Regius Professor of Engineering at the University of Edinburgh. The critical article was most valuable to Darwin. In 1869 he wrote to Alfred Russel Wallace: "Fleming Jenkyn’s arguments have convinced me". Darwin's son Francis said that Jenkin’s critique was the most valuable ever made on his father's views. Jenkin’s article was a critique intended to be based entirely on science, unlike most other critiques which were based on religion. Jenkin humorously said in his article "we are asked to believe", suggesting he opposed the theory because it was too much like a religion.

In his article Jenkin stated that organisms could obtain adaptations through natural selection, but would never gain whole new organs for smell, hearing or sight if they had never possessed them. Jenkin further asserted that once selective pressure was removed, the population would revert to its original condition. He then introduced the 'swamping argument' to deny the possibility that an occasional monstrous individual, a saltation, could supply an escape from this state of affairs and give rise to a permanent adaptation. Jenkin made a mathematical calculation for his argument

…the advantage, whatever it may be, is utterly outbalanced by numerical inferiority. A million creatures are born; ten thousand survive to produce offspring. One of the million has twice as good a chance as any other of surviving; but the chances are fifty to one against the gifted individuals being one of the hundred survivors. No doubt, the chances are twice as great against any one other individual, but this does not prevent their being enormously in favour of some average individual. However slight the advantage may be if it is shared by half the individuals produced, it will probably be present in at least fifty-one of the survivors, and in a larger proportion of their offspring; but the chances are against the preservation of any one ‘sport’ in a numerous tribe…

Jenkin made a mistake in his calculation stating the chances are “fifty to one” where it should have been “ten thousand to one”. He continued his essay with a melodramatic story to elaborate on his calculation

... Suppose a white man to have been wrecked on an island inhabited by negroes.... Our shipwrecked hero would probably become king; he would kill a great many blacks in the struggle for existence; he would have a great many wives and children, while many of his subjects would live and die as bachelors.... Our white's qualities would certainly tend very much to preserve him to good old age, and yet he would not suffice in any number of generations to turn his subjects' descendants white.... In the first generation there will be some dozens of intelligent young mulattoes, much superior in average intelligence to the negroes. We might expect the throne for some generations to be occupied by a more or less yellow king; but can any one believe that the whole island will gradually acquire a white, or even a yellow population...?

Here is a case in which a variety was introduced, with far greater advantages than any sport every heard of, advantages tending to its preservation, and yet powerless to perpetuate the new variety.[1]

Darwin agreed that a variation originating in a single individual would not spread across a population, and would invariably be lost. Darwin stated to his colleagues that he was always aware that “swamping” would stamp out saltations. In the fifth edition of On the Origin of Species he responded:

I saw, also, that the preservation in a state of nature [as opposed to under domestication] of any occasional deviation of structure, such as a monstrosity, would be a rare event; and that, if preserved, it would generally be lost by subsequent intercrossing with ordinary individuals. Nevertheless, until reading an able and valuable article in the 'North British Review' (1867), I did not appreciate how rarely single variations, whether slight or strongly-marked could be perpetuated.[2]

Darwin concluded that natural selection must instead act upon the normal small variations in any given characteristic across all the individuals in the population.

Apart from the swamping argument Jenkin also questioned Darwin’s calculation of the earth’s age. This calculation was more worrisome for Darwin as he himself agreed that in the timespan given there would not have been enough time for natural selection to take place. Darwin needed a solution to both the swamping argument for non-saltation’s and the earths age. Darwin theorized that ‘negative selection’ by the increased destruction of non-adapted specimens would further speed up the process of natural selection. Darwin added this to the fifth edition of “On the Origin of species”. This solved for him the problem of swamping in large numbers and would shorten the evolutionary process to fit his own calculated age of the earth.

Because the ‘swamping argument’ was mostly anchored in the ‘blending inheritance’ theory. When the ‘blending inheritance’ theory was replaced by mendelian inheritance in the early 1900s the ‘swamping argument’ also became obsolete.

Notes

- Jenkin, Fleming. The Origin of Species. North British Review, June 1867, vol. 46. P. 277—318

- Darwin, Charles (1869). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (5 ed.). John Murray. p. 104.

Susan W. Morris. “Fleeming Jenkin and ‘The Origin of Species’: A Reassessment.” The British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 27, no. 3, 1994, pp. 313–343. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4027601.

See also

External links

- Bulmer, Michael. Did Jenkin’s swamping argument invalidate Darwin’s theory of natural selection? // The British Journal for the History of Science (2004), 37:3:281-297 Cambridge University Press