Sverre Petterssen

Sverre Petterssen (19 February 1898 – 31 December 1974) was a Norwegian meteorologist, prominent in the field of weather analysis and forecasting.[1]

Sverre Petterssen | |

|---|---|

Sverre Petterssen in Norwegian uniform | |

| Born | 19 February 1898 |

| Died | 31 December 1974 (aged 76) |

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | Bergen School of Meteorology |

| Known for | D-Day weather forecast |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics and Meteorology |

| Institutions | MIT |

| Doctoral students | James Murdoch Austin |

Early life

Born in Norway into a humble family, he paid for his higher education by working at the telegraph office, and a nursery provided by the armed forces that he joined as a recruit. He studied in Bergen where he met Tor Bergeron during a lecture, and was so impressed by his analysis of a 1922 storm that he joined the Bergen School of Meteorology in 1923. In the late 1920s, he worked at the Geophysical Institute in Tromsø, northern Norway.

Career

After school, he remained a weather officer in the Norwegian Air Force until 1939. He went to the US in 1935, lecturing on Norwegian meteorological theories to the US Navy and Caltech. In 1939, he was hired by MIT as head of the meteorology department and wrote two important books there: Weather analysis and forecasting (1940) and Introduction to Meteorology (1941).

With the invasion of Norway, Petterssen returned to Europe and offered his services in England to the Met Office, on loan from the Norwegian Air Force. During World War II, he served as a weather forecaster for bombing raids and special operations.

Pettersen is most remembered for his work in what has been called the most significant weather forecast in history, the D-Day forecast, where he contributed significantly to the postponement of D-day by one day from 5 to 6 June; . Three groups of meteorologists gave advice to General Eisenhower; see Weather forecasting for Operation Overlord.

Pettersen disagreed with the American USAAF team of Irving P. Krick and Ben Holtzman (as did Stagg and the British naval team). Krick and Holtzman believed that weather patterns were repeated, and that there was a weather recurring pattern in the 20s which they felt was positive. Pettersen was not always diplomatic in saying that this was nonsense and quasi-science.

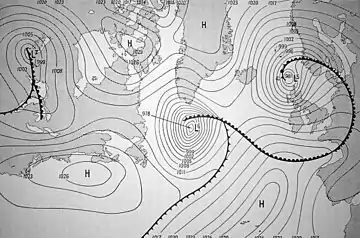

Eisenhower had originally picked 5 June for the invasion; with the option of postponing to 6 or 7 June. At the morning meeting on 4 June Pettersen presented a weather map showing a storm on 5 June. So D-Day was postponed, to strong protests from the American "quasi-meteorologists".[2][3]

But the Norwegian meteorologist knew his meteorology: His analysis showed a 36-hour gap between two storms on the morning of 6 June – just enough to make the giant attack with more than a hundred thousand soldiers, paratroopers, planes and boats."The forecast provided by Sverre Petterssen caused Eisenhower to decide at 04.30 on 4 June to postpone D-day to 6 June.

And German ships were held in port: the Kriegsmarine thought the weather was too bad for the invasion.

The next possible period after 5, 6 and 7 June was 19 June.[3] But on 19 June the worst storm to date in the century struck the English channel. If D-Day had been launched on 5 June as originally planned, the Allied casualties would probably have been much higher, and even higher if launched on 19 June.

Aftermath

In retrospect, Americans claimed – including in movies – it was their meteorologist heroes who saved the situation, and only in 1974, shortly before his death, Sverre Pettersen came with his version – documenting a violent quarrel.

The American Meteorological historian James Fleming also honored Pettersen in a report 30 years later – in 2004.[2]

Awards

- 1948 Buys Ballot Medal by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- 1965 Awarded the prestigious International Meteorological Organization Prize from the World Meteorological Organization.[4]

- 1969 Symons Gold Medal of the Royal Meteorological Society

References

- Fleming, James Rodger. "Sverre Petterssen, the Bergen School, and the forecasts for D-Day." Proceedings of the International Commission on History of Meteorology 1.1 (2004): 75-83.

- Fleming, James Rodger (2004). "Sverre Petterssen and the contentious (And momentous) weather forecasts for D-Day". Endeavour. 28 (2): 59–63. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2004.04.007. PMID 15183022.

- Harald Vikøyr (26 December 2016). "Værkrangel før D-dagen". Verdens Gang.

- "Winners of the IMO Prize". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

External links

- James R. Fleming (2004). "Sverre Petterssen, the Bergen School and the Forecasts for D-Day" (PDF). Proceedings of International Commission on History of Meteorology.