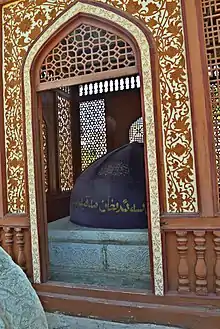

Sultan Said Khan

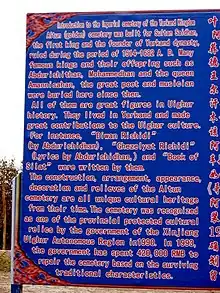

Sultan Said Khan (Uyghur: سۇلتان سەىد جان, ) ruled the Yarkent Khanate from September 1514 to July 1533. He was born in the late 15th century in Moghulistan, and he was a direct descendant of the first Moghul Khan, Tughlugh Timur, who had founded the state of Moghulistan in 1348 and ruled until 1363. The Moghuls were turkicized Mongols who had converted to Islam.

| Sultan Said Khan | |

|---|---|

| Khan of Yarkent Khanate (1514–1705) | |

| Reign | 1514–1533 |

| Predecessor | Mansur Khan |

| Successor | Abdurashid Khan |

| Born | 1487 |

| Died | 9 July 1533 (aged 45–46) near Karakoram Pass, likely Daulat Beg Oldi |

| Issue | Abdurashid Khan |

| Dynasty | Borjigin |

| Father | Ahmad Alaq |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Some English sources refer to this ruler as Abusaid.[1]

Background

.png.webp)

When the Chagatai ulus, which embraced both East and West Turkestan, collapsed, the result was the creation of two different states: Maverannahr in West Turkestan, with its capital at Samarkand, where Timur the Great came to power in 1370, and Moghulistan, with its capital at Almalik, near the present-day town of Gulja, in the Ili valley. Moghulistan embraced settled lands in Eastern Turkestan as well as nomad lands north of Tangri Tagh. The settled lands were known at the time as Manglai Sobe or Mangalai Suyah, which translates as Shiny Land, or Advanced Land Which Faced the Sun. These lands included west and central Tarim oasis-cities, such as Khotan, Yarkand, Yangihisar, Kashgar, Aksu, and Uch Turpan; and hardly involved eastern Tangri Tagh oasis-cities, such as Kucha, Karashahr, Turpan and Kumul, where a local Uyghur administration and Buddhist population still existed. The nomadic areas comprised the present Kyrgyzstan and part of Kazakhstan, including Jettisu, the area of seven rivers.

The ruler of Aksu, the dughlat emir Puladchi, brought a young, 18-year-old, Tughluk Timur from the Ili valley in 1347, and in a kurultai declared him a grandson of Duwa Khan, the great-grandson of Chagatai Khan and ruler of the Chagatai Khanate between 1282 and 1307. Puladchi forced all moghuls to recognize Tughluk as Khan. Khans from Chagatai, the second son of Genghis Khan, to Tughluk Timur are known as "Chagatai khans", and from Tughluk Timur to his descendants as "Moghul khans".

Moghulistan existed around 100 years, and then split into three parts: Yarkand state (mamlakati Yarkand), with its capital at Yarkand, which embraced all the settled lands of Western Kashgaria, still nomad Moghulistan which embraced the nomad lands north of Tengri Tagh, and Uyghurstan which embraced the settled lands of Eastern Kashgaria, Turpan and Kumul Basins. The founder of Yarkand state was Mirza Abu Bakr, who was from the dughlat tribe. In 1465, he raised a rebellion, captured Yarkand, Kashgar, and Khotan, and declared himself an independent ruler, successfully repelling attacks by the Moghulistan rulers Yunus Khan and his son Akhmad Khan, or Ahmad Alaq, named Alach, "Slaughterer", for his war against the kalmyks. In 1462 moghul khan Dost Muhammad took residency in Aksu, denying nomad style of life, and as result Eastern Kashgaria cities, such as Aksu, Uchturpan, Bai, Kucha, Karashar, and also Turpan and Kumul, separated into Eastern Khanate or Uyghurstan.

Dughlat emirs had ruled the country that lay south of Tangri-Tagh in the Tarim Basin from the middle of the thirteenth century, on behalf of Chagatai Khan and his descendants, as their satellites. The first dughlat ruler, who received lands directly from the hands of Chagatai, was amir Babdagan or Tarkhan. The capital of the emirate was Kashgar, and the country was known as Mamlakati Kashgar. Although the emirate, representing the settled lands of Eastern Turkestan, was formally under the rule of the moghul khans, the dughlat emirs often tried to put an end to that dependence, and raised frequent rebellions, one of which resulted in the separation of Kashgar from Moghulistan for almost 15 years (1416–1435).

Mirza Abu Bakr ruled Yarkand for 48 years and his ruling was featured by creation of unique and highly effective penitentiary system, that had no analog in other countries. After discovering, by occasion, 29 large bowls, filled with gold sand and silver coins (Balysh), during excavation in the old city of Yarkand, Mirza Abu Bakr ordered to start excavations throughout the whole country in all old cities of towns and in abounded cities of Taklamakan Desert as well. To get workforce for performing of mass excavations he used convicts, both males and females of any age. The place of site of excavation was named Kazyk and numerous barracks for convicts and the guards were erected, convicts were sent to Kazyks by stages from all over the country and excavation works were continuing the whole year without interruptions. Using this forced labour system he collected during his reign very large amount of treasuries and became the owner of very rare and valuable things, some of them hundreds and thousands years old.

In May 1514, Sultan Said Khan, grandson of Yunus Khan (ruler of Moghulistan between 1462 and 1487) and the third son of Akhmad Khan, made an expedition against Kashgar from Andijan with only 5,000 tribesmen (who represented 9 Moghul tribes- Dughlat, Duhtui, Barlas, Yarki, Ordabegi, Itarchi, Konchi, Churas and Bekchi), and having captured the Yangihisar citadel, that defended Kashgar from south road, took the city, dethroning Mirza Abu Bakr. Soon after, other cities of Yarkand state – Yarkand, Khotan, Aksu, and Uch Turpan – joined him, and recognized Sultan Said Khan as a ruler, creating a union of six cities, called Altishahr. Sultan Said Khan's sudden success is considered to be contributed to by the dissatisfaction of the population with the tyrannical rule of Mirza Abu-Bakr and the unwillingness of the dughlat amirs to fight against a descendant of Chagatai Khan, and who decided, on the contrary, to bring the head of the slain ruler to Sultan Said Khan. This move put an end to almost 300 years of rule (nominal and actual) by the Dughlat emirs in the cities of West Kashgaria (1219–1514). Mirza Abu Bakr fled Yarkand for Ladakh with handful of his followers and 900 donkeys, loaded with his numerous treasuries, and being chased on his heels by Dughlat emirs and also Barlas emirs, sent by Sultan Said Khan. They almost reached him in Karangu Tagh Mountains, but Mirza Abu Bakr managed to escape by killing all 900 donkeys and dumping all treasuries into Karakash River. During flight he found that all garrisons, that he previously deployed in Kashmir and Little Tibet (Ladakh), were deserted by his troops. So, he found it's impossible to stay in Ladakh, he decided to turn back and surrender to Sultan Said Khan but on half-way to Yarkand was captured and slaughtered by Dughlat emirs, who betrayed him.

Life

At this time, almost all of West Turkestan (Maverannahr) was invaded by nomadic Uzbeks of Shaybani Khan, who were killing all the descendants of Timur the Great and Chagatai Khan. Sultan Said Khan saved his life when he moved to Kashgar with his nobles. In 1516, he concluded a peace agreement with his older brother Mansur Khan, the moghul khan of Chalish and Turpan (Uyghurstan), who died in 1543. As a result, the eastern part of the settled country south and partly north of Tangri-Tagh joined his state, including the cities of Bai, Kucha, Chalish (Karashahr), Urum (Urumchi), Turpan, Kumul, and Shazhou (Dunhuang), representing those lands of former Uyghuria (856–1335) that were known as the Fifth Ulus of the Mongol Empire in the middle of the thirteenth century, because the former ruler of Uyghuria, idikut Baurchuk Art Tekin married Altun Begi, the daughter of Genghis Khan, and was declared by Genghis as his fifth son in 1211.[2]

Relations between Yarkand Khanate and Ming dynasty China were not developed, although the far eastern boundaries of Yarkand reached the Jiayuguan Pass at the western end of the Great Wall of China due to holy expeditions of Mansur Khan, including expeditions against the Sarigh Uyghurs – Yellow Uyghurs or Uyghurs of yellow religion, called Yugurs, who worshipped Tibetan Buddhism and took refuge in Gansu province of Ming China in 1529, fleeing the holy warriors of Mansur Khan. This situation can be partly explained by the full extinction of Silk Road trade by this time.

Before his death during almost 20 years of ruling he united all the settled country south of Tangri Tagh, from Kashgar to Kumul, into one centralized state- Yarkand Khanate with a population of the same origin and language. Also such mountainous regions as Kashmir and Bolor became dependencies of Yarkand Khanate, paid tributes and struck silver and golder coins under name "Abul Fath Sultan Said Khan Ghazi". The contemporary writer dughlat amir Mirza Muhammad Haidar stated that it was a time when the Power of Tyranny (the rule of Mirza Abu Bakr) had been changed to the Power of Law and Order during the rule of Sultan Said Khan. Theft of property was considered a high crime and was subject to severe punishment, including execution. Peasants were encouraged to leave their tools in the fields after work, and household owners to keep the doors of their houses unlocked. Foreign traders, upon arrival to any town, could leave their luggage dumped directly on the road and, after taking a rest for several days and returning, they could find their goods in the same place – safe and untouched.

Said Khan had a close relationship with Babur, his cousin and founder of the Mughal Empire across the Himalayas and Karakoram Range from the Yashkent Khanate.[3]

Sultan Said Khan is sometime mentioned with title of Ghazi for his military expeditions.[4] The reign of Sultan Said Khan was heavily influenced by the khojas.[5]

His reign included a campaign in Bolor in 1527–1528 with his son Rashid and Mirza Muhammad Haidar in the command of troops,[6][7] and a raid into Badakhshan in 1529[8] upon the request of its inhabitants, who temporarily were left without ruler when sick Babur recalled his eldest son Humayun Mirza from Badakhshan (ruled Badakhshan in 1520–1528) to Agra to be his successor in case of his death and who recognized Sultan Said Khan rights on Badakhshan as a grandson of Shah Begum. When Sultan Said Khan came to Badakhshan he found that youngest son of Babur Hindal Mirza was already sitting in Zafar fortress, capital of Badakhshan, while Mirza Muhammad Haidar, who was sent to Badakhshan in advance with troops, was besieging the fortress. The siege of the Zafar fortress lasted 3 months during which Babur assembled State Council in Agra and it was decided on it to avoid a war between Moghul Empire and Yarkent Khanate, Hindal Mirza was recalled to Agra and Suleiman Shah, son of the former ruler of Badakhshan Mirza Wais Khan, who died in 1520 and was a son of Timurid Sultan Mahmud Mirza and Sultan Nigar Khanum, daughter of Yunus Khan and Shah Begum, was restored as a lawful ruler of Badakhshan.

Expedition into Ladakh and death

Said Khan launched looting expeditions into Ladakh and Kashmir in 1532.[8] The account of this military expedition was recorded by his general Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, who was the Sultan's first cousin, in the work of history Tarikh-i-Rashidi (تاریخ رشیدی) (History of Rashid).[9]

In Autumn of 1531 (Safar 938 AH), the Sultan Said Khan left Yarkand with Haidar and a few thousand men. Upon first time crossing the Karakorum, the Sultan encountered severe altitude sickness, but he managed to recover. In the course of a few months of campaigning, they were able to devastate Nubra Valley. As winter approached, they split forces. The Sultan left for Baltistan; Haidar left for Kashmir. In Baltistan, the Sultan encountered a population of friendly Muslims, but he turned them killing and enslaving them, possibly because they were Shiites which was heretic to orthodox Yarkandi Sunnis. On the way to Kashmir, Haider defeated the Dras near Zoji La. In Kashmir, he and his troops were hosted by the king of Srinagar. In the spring, the two parties met up again in Maryul, the Sultan decided to return to Yarkand, but he instructed Haider to conquer Tibet for Islam before his departure.[10][11]

Sultan Said Khan purportedly died at Daulat Beg Oldi while returning to Yarkent.[12][13][4] He died in 1533 of a high-altitude pulmonary edema.[8][14] Henry Walter Bellew argues that the location of his death was here at Daulat Beg Oldi. The news of Sultan's death led to a bloody succession which saw the ascension of Abdurashid Khan. Abdurashid Khan recalled the forces in Tibet and exiled Haidar. By then, Haidar had some successes against the Changpa Tibetans of Baryang, but his forces suffered greatly from the altitude and elements. By the time the army returned to Yarkand, of the starting few thousands, less than a dozen were left. The exiled Haidar received the refuge from his maternal aunt in Badakhshan. He eventually joined the ranks of the Mughal Empire where he wrote the Tarikh-i-Rashidi.[10][11]

Aftermath

Sultan Said Khan was succeeded in Yarkand by his son, Abdur Rashid Khan (Abdurashid Khan), who ruled from 1533 to 1560.

The historian Mirza Muhammad Haidar, in 1546, called the eastern part of the country the "Eastern Khanate or Uyghurstan" in his famous book Tarikh-i- Rashidi, written in Kashmir. The capital of this state was Yarkand, and it was known by the names mamlakati Saidiya, mamlakati Yarkand, and mamlakati Moghuliya in Iranian sources. The last name however was not accurate, because by this time the nomad state of Moghulistan had collapsed. It was eliminated during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by nomadic tribes of Kyrgyz, Kazakhs and Jungars, that captured all the Moghul lands north of Tangri Tagh. The remnants of the Moghuls (about 5,000 families mostly from Barlas, Churas and Arlat tribes) moved to Kashgaria and mixed with the local 1,000 000 Uyghur population, although a group of the Moghuls, numbering 30,000 men, joined Babur, a descendant of Timur the Great through his father Omar Sheikh Mirza, and a descendant of Chagatai Khan through his mother Kutluk Nigar Khanum, a daughter of the Moghul Yunus Khan, in Kunduz, in 1512, and helped him in his invasion of India. The Babur state in India was known as the Moghul Empire, and this state recognized Yarkand Khanate in 1529, (when Babur and Sultan Said Khan peacefully settled issue around Badakhshan, that was claimed by both cousins as their hereditary Land) as it did the Shaybanid state in Maverannahr, in 1538.

This country was later known as "Kashgar and Uyghurstan", according to Balkh historian Makhmud ibn Vali ("Bahr al-Asrar", Sea of Mysteries, 1641–1644). Kashgar historian Muhammad Imin Sadr Kashgari called the country Uyghurstan in his book Traces of Invasion (Asar al-futuh) in 1780 (as opposed to Jungaria, which he called Moghulistan, and the Ili River valley, which he called Baghistan, i.e. Land of Gardens). He wrote that this great country embraced a union of six cities south of Tangri Tagh – Kashgar, Yangihisar, Yarkand, Khotan, Aksu (Ardabil), and Uch Turpan (Safidkuh) – the so-called Altishahr, as well as Kucha, Chalish (Karashahr), Turpan and Kumul. According to him, the country collapsed not due to attacks by external enemies, but due to the personal ambitions of its religious leaders, the Khojas. The Khojas were divided into two hostile groups that hated and killed each other – the Ak Taghliks (White Mountaineers) and the Kara Taghliks (Black Mountaineers), who deposed one of the last Moghul Khans, Ismail Khan, in 1678, with the help of invited Kalmyks (Dzungars), and put the whole country under the feet of future invaders, including Dzungar Khanate and Qing dynasty of China, for gaining personal powers.

Family

- Consorts

- Zainab Sultan Khanum, daughter of Mahmud Khan Chaghatai and Said's favourite wife, mother of Ibrahim Khan, Muhsin Khan and Mahmud Yusuf;[17]

- Makhduma Begum, sister of Suqar Bahadur Qaluchi, mother of Abdurashid Khan;[17]

- Habiba Sultan Khanish, daughter of Muhammad Husayn Mirza Dughlat and Khub Nigar Khanum, daughter of Yunus Khan;[17]

- Children

- Abdurashid Khan;

- Ibrahim Khan;

- Muhsin Khan;

- Mahmud Yusuf;

- Badi-ul-Jamal Khanum, married firstly to Baush Sultan of the Uzbeg Kazaks, married secondly to Muhammadi Barlas, a peasant;[17]

Genealogy of Moghul Khans of Yarkent Khanate

In Babr Nama written by Babur, Page 19, Chapter 1; described genealogy of his maternal grandfather Yunas Khan as:

"Yūnas Khān descended from Chaghatāī Khān, the second son of Chīngīz Khān (as follows,) Yūnas Khān, son of Wais Khān, son of Sher-'alī Aūghlān, son of Muḥammad Khān, son of Khiẓr Khwāja Khān, son of Tūghlūq-tīmūr Khān, son of Aīsān-būghā Khān, son of Dāwā Khān, son of Barāq Khān, son of Yīsūntawā Khān, son of Mūātūkān, son of Chaghatāī Khān, son of Chīngīz Khān"[18]

|

|

|

|

List of Kumul Khanate Khans

The list of the Kumul Khanate Khans is as follows:[19]

| Generation | Name | reign years | information |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st generation | Abdullah Beg 額貝都拉 é-bèi-dōu-lā | 1697-1709 | In the 36th year of the Kangxi reign, he was granted the title of Jasagh Darhan of the First Rank. He died in the 48th year of Kangxi's reign. |

| 2nd generation | 郭帕 guō-pà, Gapur Beg | 1709-1711 | Abdullah Beg's eldest son. In the 48th year of Kangxi's reign he was granted the title of Jasagh Darhan of the First Rank. He died in the fiftieth year of Kangxi's reign. |

| 3rd generation | Emin 額敏 É-mǐn | 1711-1740 | Gapur beg's eldest son. In the fiftieth year of Kangxi's reign he inherited the title of Jasagh Darhan of the First Rank. In the fifth year of Yongzheng's reign he was promoted to Zhenguo Gong (鎮國公) (Duke Who Guards the State); in the 7th year of Yongzheng's reign, he was promoted to Gushan Beizi (固山貝子) (Banner Prince). In the 5th year of Qianlong's reign he died. |

| 4th generation | Yusuf 玉素甫 Yù-sù-fǔ or Yusup 玉素卜yù sù bǔ | 1740-1767 | Emin's eldest son. In the fifth year of Qianlong's reign he inherited the title of Jasagh Zhenguo Gong. In the 10th year of Qianlong's reign he was promoted to Gushan Beizi. In the 23rd year of Qianlong's reign he was granted the title of Beile pinji (貝勒品級). In the 24th year of Qianlong's reign, he was conferred the title of Duoluo Beile (多羅貝勒), and conferred the title of Junwang pinji (郡王品級). He died in the 12th month of the 31st year (January 1767). |

| 5th generation | Ishaq 伊薩克 yī-sà-kè | 1767-1780 | Yusuf's second son. In the 32nd year of Qianlong's reign he inherited the title of Junwang pinji Jasagh Duoluo Beile. In the 45th year he died. |

| 6th generation | Ardashir 額爾德錫爾 é-Ěr-dé-xī-ěr | 1780-1813 | Ishaq's eldest son. In the 45th year of Qianlong's reign, he inherited the title of Junwang pinji Jasagh duoluo beile. In the 48th year by imperial order he was granted permanent succession (all his descendants would automatically inherit his title). In the 18th year of the Jiaqing Emperor he died. |

| 7th generation | Bashir 博錫爾 bó-xī-ěr | 1813-1867 | Son of é-Ěr-dé-xī-ěr. In the 18th year of Jiaqing's reign, he inherited (his father's titles). In the 12th year of Daoguang's reign, he was promoted to Duoluo Junwang 多羅郡王. In the third year of Xianfeng's reign, he was granted the title of Qinwang 親王. In the fifth year of Tongzhi's reign, the Dungan revolt broke out, but he stayed loyal (to the Qing). In the sixth year of Tongzhi's reign, he was posthumously granted the title of Hezhuo Qinwang 和碩親王. |

| 8th generation | Muhammad 賣哈莫特 mài-hǎ-mò-tè | 1867-1882 | Son of bó-xī-ěr. In the sixth year of Tongzhi's reign he inherited the title of Jasagh Heshuo Qinwang. In the seventh year of Guangxu's reign, he died, leaving no one to succeed to his title. |

| 9th generation | Maqsud Shah Maqsud Shah 沙木胡索特 shā-mù-hú-suǒ-tè | 1882-1930 | Muhammad's agnatic nephew. In the eighth year of Guangxu's reign he inherited his titles. In the fourth year of the Republic of China, his salary as qinwang was doubled. In the 19th year of the Republic of China on the sixth month on the sixth day, he died of illness. |

| 10th generation | Nasir 聶滋爾 niè-zī-ěr | 1930-1934 | Maqsud Shah's second son. In the 19th year of the Republic of China on the 9th month on the 13th day he inherited his titles. In the 23rd year of the Republic he died. |

| 11th generation | Bashir 伯錫爾 bó-xī-ěr | 1934-1949 | Nasir's eldest son. In the 23rd year of the Republic on the fourth month he inherited his titles. He was arrested and sent to prison. In 1951 he died while in prison. |

References

- "The Journey of Benedict Goës from Agra to Cathay" – Henry Yule's translation of the relevant chapters of De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas, with detailed notes and an introduction. In: Yule, Henry, ed. (1866). Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China. Translated by Yule, Henry. Printed for the Hakluyt Society. p. 546.

- Yuan Shi, volume 122 which contains the biography of Baurchuk Art Tekin, composed in 1370 by official Bureau of History in Ming dynasty China as the official chronicle of Yuan dynasty.

- Bano, Majida (2002). "Mughal relations with the Kashghar Khanate". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 63: 1116–1119. JSTOR 44158181.

Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, and Sa'id Khan were cousins, and the relationship was recognised in Babu'r memories. In a sense the Khanate and the Mughal Empire were built together, though there could be no military cooperation between the two, given the heights of the Hamalayas and the Karakoram Range that separated the two states.

- Bhattacharji, Romesh (2012). Ladakh: Changing, Yet Unchanged. Rupa Publications. ISBN 978-8129117618.

Some 400 years earlier, in ad 1527, a Yarkandi invader, Sultan Saiad Khan Ghazi (also known as Daulat Beg) of Yarkand, briefly conquered Kashmir after fighting a battle along this pass. He died in 1531 at Daulat Beg Oldi (meaning, where Daulat Beg died) at the foot of the Karakoram pass, after he was returning from an unsuccessful attempt to invade Tibet.

- Grousset, p. 500

- Holdich, Thomas Hungerford (1906). Tibet: The Mysterious. New York: Frederick A. Stokes. p. 61.

- Cacopardo, Alberto M.; Cacopardo, Augusto S. (2001). Gates of Peristan: History, Religion and Society in the Hindu Kush. Rome: Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente. p. 47. ISBN 9788863231496.

Mirza Haidar who led in 934/1527-28 an Islamic incursion into "Balur", describing it as "an infidel country (Kafiristan)" inhabited by "mountaineers" without any "religion or a creed" (Mirza Haidar 1895: 384), located "between Badakhshan and Kashmir" (ibid.: 136).

- Baumer, Christoph (2018). The History of Central Asia: The Age of Decline and Revival. Vol. 4. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-183860-867-5.

- Bellew, Henry Walter (1875). The History of Káshgharia. Calcutta: Foreign Department Press. pp. 66–67.

(p66) Daulat Beg Uild ... "The lord of the State died" ... (p67) Hydar ... wrote the Tarikhi Rashidi from which these details are derived

- Kohli, Harish (2000). Across the Frozen Himalaya: The Epic Winter Ski Traverse from Karakoram to Lipu Lekh. New Delhi: Indus Publishing. pp. 66–67. ISBN 81-7387-106-X.

According to H.W. Bellew, he was no ordinary traveller but a great warrior, a partisan of Babur, the conqueror of Ferghana and the king of Yarkand and Kashgar.

- Bellew, Henry Walter (1875). "Kashmir and Kashghar: A Narrative of the Journey of the Embassy to Kashghar in 1873–74". Ludgate Hill: Trübner & Co. pp. 95–98 – via Internet Archive.

- von Le Coq, Albert (2018) [First published 1926]. Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan: An Account of the Activities and Adventures of the Second and Third German Turfan Expeditions. Oxford: Routledge. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-429-87141-2.

Daulat Bak Oldi (the royal prince died here), close to the Karakorum pass, is so called because the Sultan Said Khan of Kashgar, on his return from a successful campaign against West Tibet, died here from mountain sickness (Plate 50)

- Howard, Neil; Howard, Kath (2014). "Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley, Eastern Ladakh, and a Consideration of Their Relationship to the History of Ladakh and Maryul". In Lo Bue, Erberto; Bray, John (eds.). Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-Cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakoram. Leiden: Brill. p. 88. ISBN 9789004271807.

When his Khan decided to return home because of ill health, leaving Mirza Haidar to destroy 'the idol temple of Ursang (i.e. Lhasa)', he 'set out from Maryul in Tibet, for Yarkand'. [...] He 'crossed the pass of Sakri', which must be that above Sakti (not the Kardung pass as Elias and Ross suggest), descended to Nubra and died at a camping place named Daulat Beg Uldi which is two-and-a-half hours below the Karakoram Pass.

- Akimushkin, Oleg F. (2005). "The Alliance of the Chaghataids of Eastern Turkestan and of the Shibanids of Mawarannahr Against the Qazakhs in the Middle of the 16th Century". In Rasuly-Paleczek, Gabriele; Katschnig, Julia (eds.). Central Asia on Display: Proceedings of the VII Conference of the European Society for Central Asian Studies. Vol. 2. Wien: LIT Verlag Münster. p. 29. ISBN 3-8258-8586-0.

On the 16th dhu-l-hiddjja 939/July 9th, 1533, on the way back from campaign in Minor Tibet (Ladakh) the founder of the Moghuliyya-Chaghataid state in Eastern Turkestan, Sultan Said-khan died.

- "Fragment de cénotaphe au nom d'Abu al-Ghazi Sultan Bahadur Khan". 1530.

- "Fragment de cénotaphe au nom d'Abu al-Ghazi Sultan Bahadur Khan". 1530.

- Gul-badan Begam (1902). The History of Humāyūn (Humāyūn-nāma). London: Royal Asiatic Society. pp. 213, 235–236, 261, 295.

- Zahiru'd-din Muḥammad Bābur Pādshāh Ghāzi (1922). The Bābur-nāma in English (Memoirs of Bābur). Vol. 1. Translated by Beveridge, Annette Susannah. London: Sold by Luzac & Co. p. 19.

- 《清史稿》卷二百十一 表五十一/藩部世表三

Bibliography

- Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat. Tarikh-i-Rashidi. Translated and edited by Elias & Denison Ross (London, 1898)

- Makhmud ibn Vali. "Bahr al-Asrar" (Sea of mysteries). Written in Balkh in 7 volumes in 1641–1644. Translated from the Balkh original text by B. Akhmedov. (Tashkent, 1977)

- Muhammad Imin Sadr Kashgari. Asar al-futuh (Traces of Invasion). Original manuscript (never published, written in 1780 in Samarkand in Uighur language by the exiled author) in custody of Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences, No.753, in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

- Kutlukov, M. Mongol rule in Eastern Turkestan. (Moscow, Nauka, 1970)

- Kutlukov, M. About emergence of Yarkand state. (Almaty, Gylym, 1990)