Rapid strep test

The rapid strep test (RST) is a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) that is widely used in clinics to assist in the diagnosis of bacterial pharyngitis caused by group A streptococci (GAS), sometimes termed strep throat. There are currently several types of rapid strep test in use, each employing a distinct technology. However, they all work by detecting the presence of GAS in the throat of a person by responding to GAS-specific antigens on a throat swab.

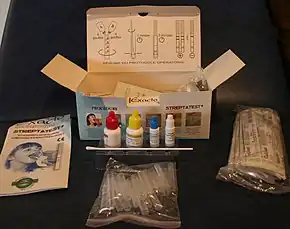

| Rapid strep test | |

|---|---|

Rapid strep test kit | |

| MedlinePlus | 003745 |

| LOINC | 78012-2 |

Medical use

A rapid strep test may assist a clinician in deciding whether to prescribe an antibiotic to a person with pharyngitis, a common infection of the throat.[1] Viral infections are responsible for the majority of pharyngitis, but a significant proportion (20% to 40% in children and 5% to 15% in adults) is caused by bacterial infection.[2] The symptoms of viral and bacterial infection may be indistinguishable, but only bacterial pharyngitis can be effectively treated by antibiotics. Since the major cause of bacterial pharyngitis is GAS, the presence of this organism in a person's throat may be seen as a necessary condition for prescribing antibiotics.[3] GAS pharyngitis is a self-limiting infection that will usually resolve within a week without medication. However, antibiotics may reduce the length and severity of the illness and reduce the risk of certain rare but serious complications, including rheumatic heart disease.[2]

RSTs may also have a public health benefit. In addition to undesirable side-effects in the individual, inappropriate antibiotic use is thought to contribute to the development of drug-resistant strains of bacteria. By helping to identify bacterial infection, RSTs may help to limit the use of antibiotics in viral illnesses, where they are not beneficial.[3]

Some clinical guidelines recommend the use of RSTs in people with pharyngitis, but others do not. US guidelines are more consistently in favor of their use than their European equivalents. The use of RSTs may be most beneficial in the third world, where the complications of streptococcal infection are most prevalent, but their use in these regions has not been well studied.[2]

Microbial culture from a throat swab is a reliable and affordable alternative to an RST which has high sensitivity and specificity. However, a culture requires special facilities and usually takes 48 hours to give a result, whereas an RST can give a result within several minutes.[3]

Procedure

The person’s throat is first swabbed to collect a sample of mucus. In most RSTs, this mucus sample is then exposed to a reagent containing antibodies that will bind specifically to a GAS antigen. A positive result is signified by a certain visible reaction. There are three major types of RST: First, a latex fixation test, which was developed in the 1980s and is largely obsolete. It employs latex beads covered with antigens that will visibly agglutinate around GAS antibodies if these are present. Second, a lateral flow test, which is currently the most widely used RST. The sample is applied to a strip of nitrocellulose film and, if GAS antigens are present, these will migrate along the film to form a visible line of antigen bound to labeled antibodies. Third, optical immunoassay is the newest and more expensive test. It involves mixing the sample with labeled antibodies and then with a special substrate on a film which changes colour to signal the presence or absence of GAS antigen.[4]

Interpretation

The specificity of RSTs for the presence of GAS is at least 95%,[3] with some studies finding close to 100% specificity.[5] Therefore, if the test result is positive, the presence of GAS is highly likely. However, 5% to 20% of individuals carry GAS in their throats without symptomatic infection, so the presence of GAS in an individual with pharyngitis does not prove that this organism is responsible for the infection.[2] The sensitivity of lateral flow RSTs is somewhat low at 65% to 80%.[2] Therefore, a negative result from such a test cannot be used to exclude GAS pharyngitis, a considerable disadvantage compared with microbial culture, which has a sensitivity of 90% to 95%.[3] However, optical immunoassay RSTs have been found to have a much higher sensitivity of 94%.[6]

Although an RST cannot distinguish GAS infection from asymptomatic carriage of the organism, most authorities recommend antibiotic treatment in the event of a positive RST result from a person with a sore throat.[4] US guidelines recommend following up a negative result with a microbial culture,[7] whereas European guidelines suggest relying on the negative RST.[8]

See also

References

- Mersch, John (20 February 2015). "Rapid strep test". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Matthys, J; De Meyere, M; van Driel, ML; De Sutter, A (Sep–Oct 2007). "Differences among international pharyngitis guidelines: not just academic". Annals of Family Medicine. 5 (5): 436–43. doi:10.1370/afm.741. PMC 2000301. PMID 17893386.

- Danchin, Margaret; Curtis, Nigel; Carapetis, Jonathan; Nolan, Terence (2002). "Treatment of sore throat in light of the Cochrane verdict: is the jury still out?". Medical Journal of Australia. 177 (9): 512–5. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04925.x. PMID 12405896. S2CID 1957427.

- Cohen, Jeremie; Cohen, Robert; Chalumeau, Martin (2013). Chalumeau, Martin (ed.). "Rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus in children with pharyngitis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010502.

- Cohen, JF; Cohen, R; Bidet, P; Levy, C; Deberdt, P; d'Humières, C; Liguori, S; Corrard, F; Thollot, F; Mariani-Kurkdjian, P; Chalumeau, M; Bingen, E (Jun 2013). "Rapid-antigen detection tests for group a streptococcal pharyngitis: revisiting false-positive results using polymerase chain reaction testing". The Journal of Pediatrics. 162 (6): 1282–4, 1284.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.01.050. PMID 23465407.

- Gerber, MA; Tanz, RR; Kabat, W; Dennis, E; Bell, GL; Kaplan, EL; Shulman, ST (Mar 19, 1997). "Optical immunoassay test for group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. An office-based, multicenter investigation". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 277 (11): 899–903. doi:10.1001/jama.277.11.899. PMID 9062328.

- Gerber, M; Baltimore, R; Eaton, C; Gewitz, M; Rowley, A; Shulman, S (2009). "Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics". Circulation. 119 (11): 1541–51. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.191959. PMID 19246689.

- Pelucci, C; Grigoryan, L; Galeone, C; Esposito, S; Huovinen, P; Little, P; Verheij, T (2012). "Guideline for the management of acute sore throat". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 18 Suppl 1: 1–28. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03766.x. PMID 22432746.