Stokes Croft

Stokes Croft is a road in Bristol, England. It is part of the A38, a main road north of the city centre. Locals refer to the area around the road by the same name.

Stokes Croft in 2009 at night | |

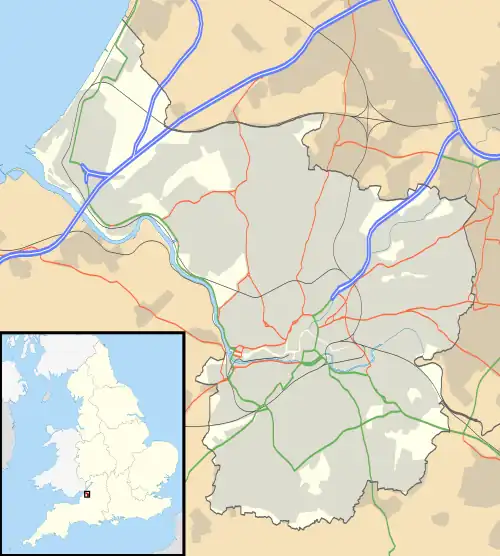

Shown within Bristol | |

| Part of | A38 |

|---|---|

| Length | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) |

| Coordinates | 51.462°N 2.59°W |

| Other | |

| Known for | |

The road became a centre of industry during the mid-19th century, including the Carriage Works. The area was damaged by aerial bombing during the Bristol Blitz in World War II, and was subsequently blighted by a plan to widen this part of the A38, but in more recent times it has rebuilt itself as a centre of art, music and counter-cultural lifestyle. Banksy's mural The Mild Mild West is on Stokes Croft. A protest was held in response to the opening of a Tesco Express on Cheltenham Road, which developed into a riot after opposition by the police. Later investigations suggested that frustration toward the new shop was entwined with other local tensions brought on by years of bad financial management by Bristol City Council.

Geography

The road is around 0.2 miles (0.32 km) long and begins as a continuation of North Street, immediately north of Bristol city centre. At the junction with Ashley Road, it then becomes Cheltenham Road, followed by Gloucester Road. The road forms part of the A38, which was once a main road north of Bristol, though long-distance traffic now takes other routes.[1]

Stokes Croft forms the boundary between the districts of Kingsdown and St Paul's and comes under the BS1 postcode.[2]

History

The road takes its name from John Stokes, mayor of Bristol in the late 14th century.[3][4] His will recorded the area as "Berewykse Croft in Redeland", while the will of Nicholas Excestre, who died in 1434, named it "formerly John Stoke's close (ibid.)".[5] It runs through the historic manor of Barton, which was recorded in the Domesday Book and part of the City of Bristol since 1373.[4]

Stokes Croft was predominantly rural until around 1700, being mainly used for market gardening. Urban development was first logged in the parish records of 1678, while St James Square, to the west of Stokes Croft, was laid out by around 1710.[5] John Roque's map of Bristol 1750 shows the area built up and running north of a central courtyard between Stokes Croft, North Street and Wilder Street.[4] Though industries were established on Stokes Croft during the 18th century, the road was not fully developed and built-up until around 1850. Construction of the Carriage Works at No. 104 began in 1859,[5] while the City Road Baptist Church was built in 1861.[6]

The area was damaged badly in World War II, with many buildings destroyed on Stokes Croft and King Square.[7] Postwar redevelopment was slow, as Bristol City Council tended to concentrate on building offices to the south, closer to the city centre, and social housing to the north, towards Gloucester Road. Development was also affected by a postwar plan to widen Stokes Croft and Cheltenham Road into a dual carriageway.[8] Owing to the lack of large-scale development, small and independent businesses set up on Stokes Croft, which contributed to the bohemian character of the street.[5] In the 1960s, the completion of the M32 motorway meant that Stokes Croft was no longer the main road from Bristol City centre northwards.[9]

Community

Stokes Croft also refers to an area around the road as an informal district between Kingsdown and St Paul's in Bristol, including Jamaica Street and the southern part of Cheltenham Road. It is not an official area of Bristol, but rather a nickname given by locals.[9] The area is a centre of art, music and independent shops in Bristol,[10] with clubs such as the Crofters Rights, Lakota and the Love Inn; the nearby music college BIMM Bristol on King Square; numerous pieces of graffiti art and one of Bristol's oldest musical instrument stores in Mickleburgh Musical Instruments Ltd.[11] The area’s character has given rise to a group of activists and artists calling themselves The People's Republic of Stokes Croft (PRSC), who are seeking to revitalise the area through community action and public art.[12]

Today the area is known for its derelict housing, squats, anarchist activity, counterculture and alternative nightlife. The Carriage Works has been designated by English Heritage as a grade II* listed building, and was regenerated as a mixed-use residential and commercial development in 2022.[13]

In 2006 a Heritage Lottery Fund grant was obtained by Bristol City Council to help overturn the decline in economic activity and environmental quality and a rise in social problems seen in the area since the 1970s.[14]

At the junction of Stokes Croft and Jamaica Street is a large mural,"The Mild Mild West", painted in 1998 by Banksy. It depicts a teddybear lobbing a Molotov cocktail at three riot police.[15] In 2007 the mural was voted Alternative Landmark of Bristol.[16]

The attraction of Stokes Croft has brought up property prices in the area, with a typical terraced house costing around £250,000 – £350,000.[17] A 2015 report in The Sunday Times suggested that Stokes Croft was one of the best urban areas to live in the South West.[18]

Incidents

In 1837, rioting broke out after the annual St James Fair in Stoke's Croft was cancelled, following continual complaints from local landowners about excessive drinking, gambling and prostitution.[19]

In April 2011, the local community protested against the opening of a new Tesco Express store at 138–142 Cheltenham Road, just north of Stokes Croft, spearheaded by the group, "No Tesco In Stokes Croft".[20] In anticipation of demonstrations of the new store, which opened on 15 April, Tesco had put in place additional security measures.[21] Various protests took place outside and inside the store during the seven days after its low-key opening. Although most protesters were peaceful, a minority threw paint and urinated on the shopfront.[19][22]

On 21 April the police evicted squatters from a property opposite the store (known as 'Telepathic Heights'). This action led to a riot involving many people and lasting for much of the night, during which the shop-front of the Tesco Store was damaged and some looting took place.[23] Further confrontations between police and protesters occurred in the early hours of 29 April.

References

Citations

- "20 Stokes Croft to 123 Stokes Croft". Google Maps. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Bristol Postcode District". Postcode Area. CliqTo Ltd. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "What's In A Name – Stokes Croft". Bristol Information. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- Etheridge & Young 2009, p. 5.

- Etheridge & Young 2009, p. 9.

- "City Road Baptist Chapel and attached steps and railings". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- "1946 aerial" (Map). 1946 aerial. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Unwin, T.J.; Bennett, J.B. (1966). "17 Future Road Pattern". Bristol City Centre Policy Report 1966. City and County of Bristol.

- "Geography". PRSC. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- "Gloucester Road & Stokes Croft". Visit Bristol. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- Mickleburgh Musical Instruments

- People's Republic of Stokes Croft Archived 8 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Carriageworks - PG Group". PG Group. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- "Heritage Lottery Fund announces funding for Stokes Croft regeneration". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- Banksy's mild mild west piece, Stokes Croft, Bristol

- BBC Bristol: Alternative Landmark of Bristol

- "Let's move to Stokes Croft, Bristol". The Guardian. 29 June 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Is Stokes Croft really Bristol's most stylish place to live?". The Bristol Post. 11 March 2015. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- Bowcott, Owen (22 April 2011). "Bristol riot over new Tesco store leaves eight police officers injured". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Bakare, Lanre (25 April 2011). "The solidarity of Bristol's Stokes Croft community". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Tesco defends store from potential threat". Bristol Evening Post. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- "Bristol's Cheltenham Road is lined with anger as protests continue". Bristol Evening Post. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Dutta, Kunal; Duff, Oliver (23 April 2011). "Police raid over 'petrol bomb plot' sparks Tesco riots". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

Sources

- Etheridge, David; Young, D.E.Y. (January 2009). The Full Moon Hotel and Attic Bar, No.1 North Street, Stokes Croft, Bristol Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment (PDF) (Report). Avon Archaeological Unit. Retrieved 21 July 2016.