The Subtle Body

The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America is a 2010 book on the history of yoga as exercise by the American journalist Stefanie Syman. It spans the period from the first precursors of American yoga, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thoreau, the arrival of Vivekananda, the role of Hollywood with Indra Devi, the hippie generation, and the leaders of a revived but now postural yoga such as Bikram Choudhury and Pattabhi Jois.

The first edition cover portrays a woman in Chakrasana, wheel pose | |

| Author | Stefanie Syman |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Subject | History of yoga |

| Publisher | Farrar, Straus, and Giroux |

Publication date | 2010 |

Several critics gave the book positive reviews, praising its wide range and readability; other critics gave it mixed reviews, noting its strengths, but also its lack of a strong continuous argument and its tendency to gossip.

Synopsis

Syman begins The Subtle Body by describing in turn the precursors of American yoga, namely Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thoreau. She notes that Emerson's 1856 poem Brahma concisely introduced Hindu nondualism, repudiating "sacraments, supernaturalism, biblical authority, and ... Christianity".[SB 1] Thoreau, she states, tried to practice yoga, and was seen by some as "the first American Yogi", but by others as "a misanthropic hermit".[SB 2] However, Syman identifies the dramatic[1] arrival of Vivekananda and his Raja Yoga as marking the start of modern yoga, and the key moment in this as being his appearance at the 1893 Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago.[SB 3]

From there, she presents the showman Pierre Bernard and his relative Theos Bernard, including sections detailing Pierre confusing yoga with tantric sex, complete with "lust, mummery, and black magic",[SB 4] and of Theos telling a carefully fictionalised account of his experiences with Hatha Yoga in India and Tibet.[SB 5]

The book then includes stories about a variety of straighter advocates of yoga. Syman tells the story of Margaret Woodrow Wilson, daughter of American president Woodrow Wilson, writing how she "turn[ed] Hindu" after she "found peace" in Sri Aurobindo's ashram in Pondicherry.[SB 6] A Hollywood connection is then explored, featuring Prabhavananda, who translated the Bhagavad Gita; Aldous Huxley; Alan Watts; and Indra Devi. The books explains how Devi came to America, unknown, having learnt yoga directly from Krishnamacharya, and how she had grown up in pre-revolutionary Russia, escaping to Berlin and going to India with her diplomat husband. It also tells of the times that Devi taught many celebrity pupils, including Greta Garbo and Gloria Swanson;[SB 7] in a review, Sarah Schrank notes that Syman is interested in how "American fans, often rich and female", made suitable environments for yoga to spread, "shaping celebrity gurus in the process".[2]

Then Syman gives her view that, in the 1960s, the yoga scene was dominated by celebrity gurus, whether from India like Maharishi Mahesh Yogi with his Transcendental Meditation, or home-grown like the "psychedelic sages" Ram Dass (aka Richard Alpert) and Timothy Leary, both at one time Harvard professors.[SB 8] It then tells how they were followed, towards the end of the 1960s, by Indian gurus of postural yoga, such as B. K. S. Iyengar, founder of the precise Iyengar Yoga, and Vishnudevananda, founder of the more overtly spiritual Sivananda Yoga, along with Swami Satchidananda, giving the story of how the Swami made the crowds chant "Hari Om, Rama Rama" at the 1969 Woodstock Festival.[SB 9]

The book ends with an account of the gurus of more energetic forms of yoga, in particular Bikram Choudhury and Pattabhi Jois.[SB 10][3]

Publication

The Subtle Body was published as a hardback book by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux in New York in 2010.[4]

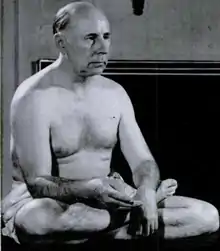

The book is illustrated[4] with 25 monochrome plates, including portraits of many of the people described. Other illustrations are of the chakras from Arthur Avalon in 1919; a circus program from 1929 showing yoga-like contortions; the Hollywood Vedanta Temple; a naked woman in Laghuvajrasana, a back bend, at the Esalen Institute in 1972; and the Sri Ganesha Temple in Ashtanga Yoga New York in 2009.

Reception

Several critics gave The Subtle Body positive reviews, praising its wide range and readability.[5][1][2][6] Other critics gave the book mixed reviews, noting its strengths, but also its lack of a strong continuous argument, its preference for colourful stories, and its tendency to gossip.[7][8]

One of the warmest receptions came in the New York Journal of Books from novelist Norman Powers. He calls Subtle Body "wide-ranging, flexible in its outlook, and satisfying in its inclusiveness, even if Ms. Syman never really defines what, exactly, yoga is." In his view, the result is "really a cultural history of the United States"; Powers notes Syman's statement that yoga "is one of the first and most successful products of globalization", and observes that in America it helped to weave an isolationist population "into the fabric of the larger world".[5] The scholar of Eastern religions Thomas Forsthoefel almost entirely agreed with Powers in his review of the book for Nova Religio, in which he called it "a compelling account of the complex social and philosophical interface"[1] created by yoga's arrival in America, also describing it as mainly a social history.[1]

Forsthoefel, though, sees the book's strength as Syman's storytelling, which he says provides "key snapshots both of the sweep of yoga's evolution in America and of the lives of key figures"[1] in that process, so that the book reads "almost like a novel".[1] The readability has been noted by academics, too: the historian Sarah Schrank, writing in American Studies, calls Subtle Body "highly readable" as it traces the various "transmutations" of yoga in America.[2] Bob Weisenberg, writing in Elephant Journal, states that the book "reads like a thriller"[6] and is "so entertaining it clearly has an audience outside the Yoga world".[6]

Among the most critical was the historian Jared Farmer. Writing in Reviews in American History, he calls the book relatively vivid but "inconstant", switching between journalistic, historical, creative, and critical writing styles. Further, in his view it "lacks a strong argument" and "privileg[es] the most colorful stories". The most extreme of those is Syman's longest chapter, on Pierre Bernard, with Farmer writing that it "includes bizarre love triangles, menage a trois, tantric sex, Vanderbilt heiresses, private detectives, spies, circus elephants, baseball, and heavyweight boxing." Though Farmer notes how Syman successfully illustrates the importance of women in shaping yoga in America, particularly Indra Devi, he affirms that today's yoga did not come straight from Devi; he instead asserts that, in the 1960s, modern yoga split into a mind-oriented stream with Transcendental Meditation and the Hare Krishnas, and a body-oriented stream with Iyengar.[7] These are covered variously in other parts of the book.[SB 8][SB 9]

In another review, the literary critic Michiko Kakutani, writing in The New York Times, states that Syman deftly traces how Emerson and Thoreau enabled yoga to take root in America, providing a "lively gallery of larger-than-life characters" in the story of American yoga. Kakutani notes Syman's many "entertaining anecdotes" but states that the book fails to cover either yoga's ancient history or to show how the various schools of yoga evolved.[3] Almost entirely disagreeing with Kakytani, Claire Dederer, writing in Slate, calls the book an "exhaustive historical survey". She notes that Syman writes of Devi that to her, yoga refers only to the asanas, calling this "a turning point ... from esoteric pursuit to health-giving practice available to all." In Dederer's view, Syman "does a wonderful job of showing how yoga, like a virus, has kept evolving in order to survive", but all the same Dederer wonders if Syman wasn't trying too hard.[9] Similarly, Tara Katir, writing in Hinduism Today, states that Subtle Body "proceeds systematically", and is "engaging, if at times a bit gossipy."[8]

See also

- Yoga Body, Mark Singleton's 2010 book on the origins of global yoga in physical culture

- Selling Yoga, Andrea Jain's 2015 book on the commercialisation of global yoga

References

Primary

These references indicate the parts of the Subtle Body text being discussed.

- Syman 2010, pp. 11–25

- Syman 2010, pp. 26–36

- Syman 2010, pp. 37–61

- Syman 2010, p. 87

- Syman 2010, pp. 80–142

- Syman 2010, pp. 143–159

- Syman 2010, pp. 179–197

- Syman 2010, pp. 198–232, 256–267

- Syman 2010, pp. 233–255

- Syman 2010, pp. 268–294

Secondary

- Forsthoefel, Thomas A. (November 2012). "Review: The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America by Stefanie Syman". Nova Religio. 16 (2): 109–110. doi:10.1525/nr.2012.16.2.109.

- Schrank, Sarah (2014). "American Yoga: The Shaping of Modern Body Culture in the United States". American Studies. 53 (1): 169–181. doi:10.1353/ams.2014.0021. S2CID 144698814.

- Kakutani, Michiko (29 July 2010). "Where the Ascetic Meets the Athletic". The New York Times. p. C23.

- The subtle body : the story of yoga in America. WorldCat. OCLC 863497740.

- Powers, Norman. "The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America". New York Journal of Books. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- Weisenberg, Bob (4 August 2010). "Elephant's First Online Book Signing "The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America" by Stefanie Syman". Elephant Journal.

- Farmer, Jared (March 2012). "Americanasana". Reviews in American History. 40 (1): 145–158. doi:10.1353/rah.2012.0016. S2CID 246283975.

- Katir, Tara (July 2010). "History of Yoga in USA". Hinduism Today.

- Dederer, Claire (11 July 2010). "Two new books explain why Americans love yoga". Slate.

Sources

- Syman, Stefanie (2010). The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-23676-2.