State income tax

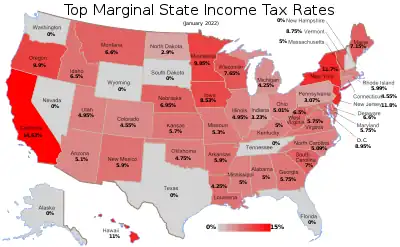

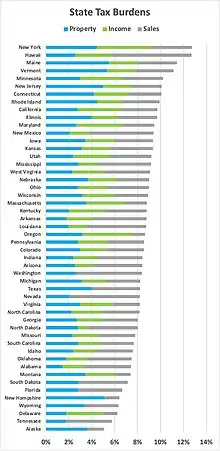

In addition to federal income tax collected by the United States, most individual U.S. states collect a state income tax. Some local governments also impose an income tax, often based on state income tax calculations. Forty-two states and many localities in the United States impose an income tax on individuals. Eight states impose no state income tax, and a ninth, New Hampshire, imposes an individual income tax on dividends and interest income but not other forms of income (though it will be phased out by 2027). Forty-seven states and many localities impose a tax on the income of corporations.[1]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Taxation in the United States |

|---|

|

|

|

State income tax is imposed at a fixed or graduated rate on taxable income of individuals, corporations, and certain estates and trusts. These tax rates vary by state and by entity type. Taxable income conforms closely to federal taxable income in most states with limited modifications.[2] States are prohibited from taxing income from federal bonds or other federal obligations. Most states do not tax Social Security benefits or interest income from obligations of that state. In computing the deduction for depreciation, several states require different useful lives and methods be used by businesses. Many states allow a standard deduction or some form of itemized deductions. States allow a variety of tax credits in computing tax.

Each state administers its own tax system. Many states also administer the tax return and collection process for localities within the state that impose income tax.

State income tax is allowed as an itemized deduction in computing federal income tax, subject to limitations for individuals.

Basic principles

% of income

State tax rules vary widely. The tax rate may be fixed for all income levels and taxpayers of a certain type, or it may be graduated. Tax rates may differ for individuals and corporations.

Most states conform to federal rules for determining:

- gross income,

- timing of recognition of income and deductions,

- most aspects of business deductions,

- characterization of business entities as either corporations, partnerships, or disregarded entities.

Gross income generally includes all income earned or received from whatever source with some exceptions. States are prohibited from taxing income from federal bonds or other federal obligations.[3] Most states also exempt income from bonds issued by that state or localities within the state as well as some portion or all of Social Security benefits. Many states provide tax exemption for certain other types of income, which varies widely by state. States uniformly allow reduction of gross income for cost of goods sold, though the computation of this amount may be subject to some modifications.

Most states provide for modification of both business and non-business deductions. All states taxing business income allow deduction for most business expenses. Many require that depreciation deductions be computed in manners different from at least some of those permitted for federal income tax purposes. For example, many states do not allow the additional first year bonus depreciation deduction.

Most states tax capital gain and dividend income in the same manner as other investment income. In this respect, individuals and corporations not resident in the state generally are not required to pay any income tax to that state with respect to such income.

Some states have alternative measures of tax. These include analogs to the federal Alternative Minimum Tax in 14 states,[4] as well as measures for corporations not based on income, such as capital stock taxes imposed by many states.

Income tax is self assessed, and individual and corporate taxpayers in all states imposing an income tax must file tax returns in each year their income exceeds certain amounts determined by each state. Returns are also required by partnerships doing business in the state. Many states require that a copy of the federal income tax return be attached to their state income tax returns. The deadline for filing returns varies by state and type of return, but for individuals in many states is the same as the federal deadline, typically April 15.

Every state, including those with no income tax, has a state taxing authority with power to examine (audit) and adjust returns filed with it. Most tax authorities have appeals procedures for audits, and all states permit taxpayers to go to court in disputes with the tax authorities. Procedures and deadlines vary widely by state. All states have a statute of limitations prohibiting the state from adjusting taxes beyond a certain period following filing returns.

All states have tax collection mechanisms. States with an income tax require employers to withhold state income tax on wages earned within the state. Some states have other withholding mechanisms, particularly with respect to partnerships. Most states require taxpayers to make quarterly estimated tax payments not expected to be satisfied by withholding tax.

All states impose penalties for failing to file required tax returns and/or pay tax when due. In addition, all states impose interest charges on late payments of tax, and generally also on additional taxes due upon adjustment by the taxing authority.

Individual income tax

Forty-three states impose a tax on the income of individuals, sometimes referred to as personal income tax. State income tax rates vary widely from state to state. States imposing an income tax on individuals tax all taxable income (as defined in the state) of residents. Such residents are allowed a credit for taxes paid to other states. Most states tax income of nonresidents earned within the state. Such income includes wages for services within the state as well as income from a business with operations in the state. Where income is from multiple sources, formulary apportionment may be required for nonresidents. Generally, wages are apportioned based on the ratio days worked in the state to total days worked.[6]

All states that impose an individual income tax allow most business deductions. However, many states impose different limits on certain deductions, especially depreciation of business assets. Most states allow non-business deductions in a manner similar to federal rules. Few allow a deduction for state income taxes, though some states allow a deduction for local income taxes. Six of the states allow a full or partial deduction for federal income tax.[7]

In addition, some states allow cities and/or counties to impose income taxes. For example, most Ohio cities and towns impose an income tax on individuals and corporations.[8] By contrast, in New York, only New York City and Yonkers impose a municipal income tax.

States with no individual income tax

Eight U.S. states and the district of Columbia do not levy a broad-based individual income tax. Some of these do tax certain forms of personal income:

- Alaska – no individual tax but has a state corporate income tax. Alaska has no state sales tax, but lets local governments collect their own sales taxes. Alaska has an annual Permanent Fund Dividend, derived from oil revenues, for all citizens living in Alaska after one calendar year, except for some convicted of criminal offenses.[9]

- Florida – no individual income tax[10] but has a 5.5% corporate income tax.[11] The state once had a tax on "intangible personal property" held on the first day of the year (stocks, bonds, mutual funds, money market funds, etc.), but it was abolished at the start of 2007.[12]

- Nevada – no individual or corporate income tax. Nevada gets most of its revenue from sales taxes as well as taxes on the gambling and mining industries.[13][14]

- New Hampshire – no individual income tax. The state taxes dividends and interest on investment income at 4% in 2023. This was set to decrease by 1% each year until it reaches 0% in 2027, but the companion bill to the 2023 budget accelerated the repeal to the start of 2025.[15] For large businesses, the 0.55% Business Enterprise Tax is essentially an income tax. The state also has a 7.6% business profits tax, scheduled to drop to 7.5% in 2024.[16]

- South Dakota – no individual income tax but has a state franchise income tax on financial institutions.[17]

- Tennessee – has no individual income tax. In 2014 voters approved an amendment to the state constitution prohibiting state or local governments from levying any income tax.[18] Prior to January 1, 2021 Tennessee had the "Hall income tax", a tax on certain interest and dividend income from investments.

- Texas – no individual income tax but imposes a franchise tax on corporations. In May 2007, the legislature modified the franchise tax by enacting a modified gross margin tax on certain businesses (sole proprietorships and some partnerships were automatically exempt; corporations with receipts below a certain level were also exempt as were corporations whose tax liability was also below a specified amount), which was amended in 2009 to increase the exemption level. The Texas Constitution bans the passage of an income tax with a 2/3 majority of the legislature required to repeal the ban.[19]

- Washington – no individual tax but has a business and occupation tax (B&O) on gross receipts, applied to "almost all businesses located or doing business in Washington." It varies from 0.138% to 1.9% depending on the type of industry.[20][21] In July 2017, the Seattle City Council unanimously approved an income tax on Seattle residents, making the city the only one in the state with an income tax.[22] It was subsequently ruled unconstitutional by the King County Superior Court.[23] The Court of Appeals upheld that ruling[24] and the Washington Supreme Court declined to hear the case, maintaining the tax as unconstitutional and unenforceable.[25] In 2022, through the Long-Term Care Trust Act, Washington began taxing high-net-worth individuals once capital gains exceeded $250,000.[26] Stakeholders advocating for adoption of this act include assisted living, adult family home, and nursing home providers; labor unions; area agencies on aging; businesses; the AARP, and more.[27]

- Wyoming – no individual or corporate income taxes.[28]

States with flat rate individual income tax

Seven states have a flat rate individual income tax:[29]

- Colorado – 4.40% (2023)

- Illinois – 4.95% (July 2017)

- Indiana – 3.23% [30] Counties may impose an additional income tax). See Taxation in Indiana[31]

- Michigan – 4.25% (2016)[32][33] (22 cities in Michigan may levy an income tax, with non-residents paying half the rate of residents)[34]

- North Carolina – 4.99% (2022)

- Pennsylvania – 3.07% [35](many municipalities in Pennsylvania assess a tax on wages: most are 1%, but can be as high as 3.75% in Philadelphia.[36] School districts may also impose an earned income tax up to Act 32 limits. [37][38] )

- Utah – 4.85% (2022)

States with local income taxes in addition to state-level income tax

Light Green - States with state-level individual income tax on interest and dividends only but no local-level individual income taxes

Yellow - States with state-level individual income tax but no local-level individual income taxes are in yellow.

Light Orange - States with state-level individual income tax and local-level individual income taxes on payroll only are in dark yellow/light orange.

Orange - States with state-level individual income tax and local-level individual income tax on interest and dividends only

Red - States with state-level and local-level individual income taxes

The following states have local income taxes. These are generally imposed at a flat rate and tend to apply to a limited set of income items.

Alabama:

- Some counties, including Macon County, and municipalities, including Birmingham (employees on payroll only)

California:

- San Francisco (payroll only)

Colorado:

- Some municipalities, including Denver and Aurora (flat-fee Occupational Privilege tax for privilege of working or conducting business; filed with municipality imposing fee)

Delaware:

- Wilmington (earned, certain Schedule E income, as well as capital gains from sale of property used in business; income must be reported to the City of Wilmington if Wilmington tax is not withheld by employer.)

Indiana (all local taxes reported on state income tax form):

- All counties

Iowa (all local taxes reported on state income tax form):

- Many school districts and Appanoose County

Kansas:

- Some counties and municipalities (interest and dividend income; reported on separate state form 200 filed with the county clerk)

Kentucky:

- Most counties, including Kenton County, Kentucky, and municipalities, including Louisville and Lexington (earned income and certain rental income that qualifies as a business; reported as Occupational License fee/tax by employer or as Net Profits tax by business, filed with county or municipality imposing tax)

Maryland (all local taxes reported on state income tax form):

- All counties, and the independent city of Baltimore

Michigan:

- Many cities, including Detroit, Lansing, and Flint (most income above a certain annual threshold; reported on form issued by imposing city or on separate state form 5118/5119/5120 in the case of Detroit)

Missouri (all other cities are prohibited from imposing local income tax):

- Kansas City (earned income; income must be reported to Kansas City if city tax is not withheld by employer; residents must file the Earnings tax form to report wages on which Kansas City income tax is not withheld and the Business Earnings tax form to report self-employment income)

- St. Louis (earned income; income must be reported to the City of St. Louis if St. Louis tax is not withheld by employer; residents must file the Earnings tax form to report wages on which St. Louis income tax is not withheld and the Business Earnings tax form to report self-employment income)

New Jersey:

- Newark (payroll only)

New York (all local taxes reported on state income tax form):

- New York City (employees with NYC section 1127 withholding should also file New York City Form 1127)

- Yonkers

- Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District (self-employed with income sourced from New York City, as well as the counties of Dutchess, Nassau, Orange, Putnam, Rockland, Suffolk, and Westchester)

Ohio:

- Some school districts (either traditional or earned income tax base; reported on separate state form SD-100).

- RITA (Regional Income Tax Agency).[39]

- Most cities and villages (more than 600[40] out of 931) on earned income and rental income. Some municipalities require all residents over a certain age to file, while others require residents to file only if municipal income tax is not withheld by employer. Income is reported on a tax form issued by the municipal income tax collector, currently Cleveland's Central Collection Agency (CCA) or the Regional Income Tax Authority (RITA), or a collecting municipality. Municipalities such as Columbus and Cincinnati sometimes also collect for neighboring towns and villages.

Oregon:

- Portland (all residents must file an Arts Tax form with the city to either pay the flat-fee tax or qualify for an exemption based on low individual or household income)

- Lane Transit District (self-employed with income sourced from Lane Transit District, which includes parts of Lane County; reported on separate state tax form LTD)

- Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District (self-employed with income sourced from TriMet, which includes parts of Clackamas, Multnomah, and Washington counties; reported on separate state tax form TM)

- Other transit districts (businesses with income sourced from those transit districts; filed with transit districts or municipalities administering transit districts)

Pennsylvania:

- Most municipalities, including Pittsburgh and Allentown, and school districts (earned income only; local return must be filed by all residents of municipality or school district imposing local earned income tax with the local earned income tax collector, such as Berkheimer, Keystone Collections, or Jordan Tax Service; an additional local services tax, potentially refundable if income is below a certain threshold, is also imposed by some municipalities and school districts on earned income sourced from those municipalities and school districts; local earned income tax collectors, rates, and local service tax refund rules can be found on the Pennsylvania Municipal Statistics website)

- Philadelphia (earned and passive income; income must be reported to the City of Philadelphia if Philadelphia tax is not withheld by employer; residents must file the Earnings tax form to report wages on which Philadelphia income tax is not withheld, the Net Profits tax form to report self-employment, business, and most rental income, and the School Income tax to report passive income excluding interest earned from checking and savings accounts; an additional Business Income and Receipts Tax is also imposed on business income sourced from Philadelphia; individuals earning less than amount that would qualify them for the Pennsylvania income tax forgiveness program are eligible to receive a partial refund of their wage tax withheld by filing a refund application)

West Virginia:

- Some municipalities, including Charleston and Huntington (flat City Service fee for privilege of working or conducting business; filed with municipality imposing fee)

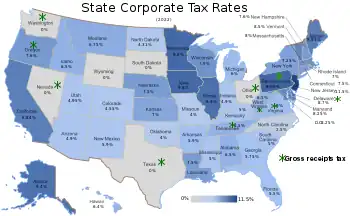

Corporate income tax

Most states impose a tax on income of corporations having sufficient connection ("nexus") with the state. Such taxes apply to U.S. and foreign corporations, and are not subject to tax treaties. Such tax is generally based on business income of the corporation apportioned to the state plus nonbusiness income only of resident corporations. Most state corporate income taxes are imposed at a flat rate and have a minimum amount of tax. Business taxable income in most states is defined, at least in part, by reference to federal taxable income.

According to taxfoundation.org, these states have no state corporate income tax as of Feb 1, 2020: Nevada, Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming. However, Nevada, Ohio, and Washington impose a gross receipts tax while Texas has a franchise tax based on "taxable margin", generally defined as sales less either cost of goods sold less compensation, with complete exemption (no tax owed) for less than $1MM in annual earnings and gradually increasing to a maximum tax of 1% based on net revenue, where net revenue can be calculated in the most advantageous of four different ways.[41][42]

Nexus

States are not permitted to tax income of a corporation unless four tests are met under Complete Auto Transit, Inc. v. Brady:[43]

- There must be a "substantial nexus" (connection) between the taxpayer's activities and the state,

- The tax must not discriminate against interstate commerce,

- The tax must be fairly apportioned, and

- There must be a fair relationship to services provided.

Substantial nexus (referred to generally as simply "nexus") is a general U.S. Constitutional requirement that is subject to interpretation, generally by the state's comptroller or tax office, and often in administrative "letter rulings".

In Quill Corp. v. North Dakota [44] the Supreme Court of the United States confirmed the holding of National Bellas Hess v. Illinois [45] that a corporation or other tax entity must maintain a physical presence in the state (such as physical property, employees, officers) for the state to be able to require it to collect sales or use tax. The Supreme Court's physical presence requirement in Quill is likely limited to sales and use tax nexus, but the Court specifically stated that it was silent with respect to all other types of taxes [44] ("Although we have not, in our review of other types of taxes, articulated the same physical-presence requirement that Bellas Hess established for sales and use taxes, that silence does not imply repudiation of the Bellas Hess rule."). Whether Quill applies to corporate income and similar taxes is a point of contention between states and taxpayers.[46] The "substantial nexus" requirement of Complete Auto, supra, has been applied to corporate income tax by numerous state supreme courts.[47]

Apportionment

The courts have held that the requirement for fair apportionment may be met by apportioning between jurisdictions all business income of a corporation based on a formula using the particular corporation's details.[48] Many states use a three factor formula, averaging the ratios of property, payroll, and sales within the state to that overall. Some states weight the formula. Some states use a single factor formula based on sales.[49]

State capital gains taxes

Most states tax capital gains as ordinary income. Most states that do not tax income (Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming) do not tax capital gains either, however two states, New Hampshire and Washington State, do tax income from dividends and interest.[50]

History

The first state income tax, as the term is understood today in the United States, was passed by the State of Wisconsin in 1911 and came into effect in 1912. However, the idea of taxing income has a long history.

Some of the English colonies in North America taxed property (mostly farmland at that time) according to its assessed produce, rather than, as now, according to assessed resale value. Some of these colonies also taxed "faculties" of making income in ways other than farming, assessed by the same people who assessed property. These taxes taken together can be considered a sort of income tax.[51] The records of no colony covered by Rabushka[52] (the colonies that became part of the United States) separated the property and faculty components, and most records indicate amounts levied rather than collected, so much is unknown about the effectiveness of these taxes, up to and including whether the faculty part was actually collected at all.

- Plymouth Colony from 1643 and Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1646, and after they merged, the Province of Massachusetts Bay until the Revolution;

- New Haven Colony from 1649 and Connecticut Colony from 1650, past the 1662 merger with New Haven, until the Revolution;

- the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, arguably from 1673 to 1744 or later;

- the Province of West Jersey, a single 1684 law;

- the "South-west part" of the Province of Carolina, later the Province of South Carolina, from 1701 until the Revolution;

- the Province of New Hampshire, arguably from 1719 to 1772 or later;

- and the Delaware Colony in the Province of Pennsylvania, from 1752 to the Revolution.

Rabushka makes it clear that Massachusetts and Connecticut actually levied these taxes regularly, while for the other colonies such levies happened much less often; South Carolina levied no direct taxes from 1704 through 1713, for example. Becker,[53] however, sees faculty taxes as routine parts of several colonies' finances, including Pennsylvania.

During and after the American Revolution, although property taxes were evolving toward the modern resale-value model, several states continued to collect faculty taxes.

- Massachusetts until 1916 (when it was replaced by a quasi-modern classified individual income tax);

- Connecticut until 1819;

- South Carolina, where the tax edged closer to a modern income tax, until 1868;

- Delaware until 1796;

- Maryland from 1777 to 1780;

- Virginia from 1777 to 1782;[54]

- New York, one 1778 levy;

- the Vermont Republic, then Vermont as a state, from 1778 to 1850;

- and Pennsylvania from 1782 to 1840 (when it was replaced by an individual income tax; Becker, as noted above, would date this tax earlier).

Between the enactment of the Constitution and 1840, no new general taxes on income appeared. In 1796, Delaware abolished its faculty tax, and in 1819 Connecticut followed suit. On the other hand, in 1835, Pennsylvania instituted a tax on bank dividends, paid by withholding, which by about 1900 produced half its total revenue.[55]

Several states, mostly in the South, instituted taxes related to income in the 1840s; some of these claimed to tax total income, while others explicitly taxed only specific categories, these latter sometimes called classified income taxes. These taxes may have been spurred by the ideals of Jacksonian democracy,[56] or by fiscal difficulties resulting from the Panic of 1837.[57] None of these taxes produced much revenue, partly because they were collected by local elected officials.

- Pennsylvania from 1840 to 1871;

- Maryland from 1841 to 1850;

- Alabama from 1843 to 1884;

- Virginia from 1843 to 1926 (when it was replaced by a modern individual income tax);

- Florida from 1845 to 1855;

- and North Carolina from 1849 to 1921 (when it was replaced by a modern individual income tax).

The 1850s brought another few income tax abolitions: Maryland and Vermont in 1850, and Florida in 1855.

During the American Civil War and Reconstruction Era, when both the United States of America (1861-1871) and the Confederate States of America (1863-1865) instituted income taxes, so did several states.[58]

As with the national taxes, these were made in various ways to produce substantial revenue, for the first time in the history of American income taxation. On the other hand, as soon as the war ended, a wave of abolitions began: Missouri in 1865, Georgia in 1866, South Carolina in 1868, Pennsylvania and Texas in 1871, and Kentucky in 1872.

The rest of the century balanced new taxes with abolitions: Delaware levied a tax on several classes of income in 1869, then abolished it in 1871; Tennessee instituted a tax on dividends and bond interest in 1883, but Kinsman reports[61] that by 1903 it had produced zero actual revenue; Alabama abolished its income tax in 1884; South Carolina instituted a new one in 1897 (eventually abolished in 1918); and Louisiana abolished its income tax in 1899.

Following the 1895 Supreme Court decision in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. which effectively ended a federal income tax, some more states instituted their own along the lines established in the 19th century:

- Oklahoma 1908 to 1915;

- Mississippi 1912 to 1924;

- Missouri, individual and corporate, from 1917.

However, other states, some perhaps spurred by Populism, some certainly by Progressivism, instituted taxes incorporating various measures long used in Europe, but considerably less common in America, such as withholding, corporate income taxation (as against earlier taxes on corporate capital), and especially the defining feature of a "modern" income tax, central administration by bureaucrats rather than local elected officials. The twin revenue-raising successes of Wisconsin's 1911 (the Wisconsin Income Tax, the first "modern" State Income Tax was passed in 1911 and came into effect in 1912) and the United States' 1914 income taxes prompted imitation.[62] Note that writers on the subject sometimes distinguish between corporate "net income" taxes, which are straightforward corporate income taxes, and corporate "franchise" taxes, which are taxes levied on corporations for doing business in a state, sometimes based on net income. Many states' constitutions were interpreted as barring direct income taxation, and franchise taxes were seen as legal ways to evade these bars.[63] The term "franchise tax" has nothing to do with the voting franchise, and franchise taxes only apply to individuals insofar as they do business. Note that some states actually levy both corporate net income taxes and corporate franchise taxes based on net income. For the following list, see [64] and.[65]

- The Territory of Hawaii, then Hawaii as a state, individual and corporate from 1901 (this is sometimes claimed as the oldest state income tax; it is certainly the oldest state corporate income tax);

- Wisconsin, individual and corporate from 1911 (generally considered the first modern state income tax, built on a law largely written by Delos Kinsman,[66] whose 1903 book on the subject is cited above; its major distinction as against older laws, including Hawaii's,[67] is that state bureaucrats rather than local assessors collected it);

- Connecticut, franchise, from 1915;

- Oklahoma, modernisation of existing individual tax, from 1915;

- Massachusetts, individual, from 1916;

- Virginia, corporate, from 1916;

- Delaware, individual, from 1917;

- Montana, franchise, from 1917;

- New York, franchise, from 1917;

- Note abolition of South Carolina's non-modern individual income tax in 1918;

- Alabama, individual, 1919, declared unconstitutional 1920;

- New Mexico, individual and corporate, 1919, apparently abolished soon thereafter;

- New York, individual, from 1919;

- North Dakota, individual and corporate, from 1919;

- Massachusetts, corporate (franchise), from 1919 or 1920;

- Mississippi's income tax was held to apply to corporations in 1921;

- North Carolina, modernisation of existing individual and institution of corporate taxes, from 1921;

- South Carolina, individual and corporate, from 1921 or 1922;

- New Hampshire, "intangibles" (restricted to interest and dividends), from 1923;

- Oregon, individual and corporate, 1923 (repealed 1924);[68]

- Tennessee, corporate, from 1923;

- Mississippi, modernisation of existing corporate and individual taxes, from 1924;

- Virginia, modernisation of existing corporate and individual taxes, from 1926.

This period coincided with the United States' acquisition of colonies, or dependencies: the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam from Spain in the Spanish–American War, 1898–99; American Samoa by agreements with local leaders, 1899-1904; the Panama Canal Zone by agreement from Panama in 1904; and the U.S. Virgin Islands purchased from Denmark in 1917. (Arguably, Alaska, purchased from Russia in 1867, and Hawaii, annexed in 1900, were also dependencies, but both were by 1903 "incorporated" in the U.S., which these others never have been.) The Panama Canal Zone was essentially a company town, but the others all began levying income taxes under American rule. (Puerto Rico already had an income tax much like a faculty tax, which remained in effect for a short time after 1898.)[69]

A third of the current state individual income taxes, and still more of the current state corporate income taxes, were instituted during the decade after the Great Depression started:[65][73][74][75]

- Arkansas, individual and corporate, from 1929;

- California, franchise, from 1929;

- Georgia, individual and corporate, from 1929;

- Oregon, individual, franchise, and intangibles, from 1929, but the individual tax didn't take effect until 1930 and was restricted to use for property tax relief, and the intangibles tax was held unconstitutional in 1930;[76]

- Tennessee, intangibles, from 1929;

- Idaho, individual and corporate, from 1931;

- Ohio, intangibles, from 1931, apparently abolished soon thereafter;

- Oklahoma, corporate, from 1931;

- Oregon, intangibles, 1931 to 1939;

- Utah, individual and franchise, from 1931;

- Vermont, individual and corporate, from 1931;

- Illinois, individual and corporate, 1932, soon declared unconstitutional;

- Washington, individual and corporate, 1932, declared unconstitutional 1933;[77]

- Alabama, individual and corporate, from 1933;

- Arizona, individual and corporate, from 1933;

- Kansas, individual and corporate, from 1933;

- Minnesota, individual, corporate, and franchise, from 1933;

- Montana, individual and corporate, from 1933;

- New Mexico, individual and corporate, from 1933;

- Iowa, individual and franchise, from 1934;

- Louisiana, individual and corporate, from 1934;

- California, individual and corporate, from 1935;

- Pennsylvania, franchise, from 1935;

- South Dakota, individual and corporate, 1935 to 1943;

- The U.S. Virgin Islands income tax in 1935 became the first "mirror" tax, for which see below;

- Washington, individual and corporate, 1935, held unconstitutional in separate decisions the same year;[77]

- West Virginia, individual, 1935 to 1942;

- Kentucky, individual and corporate, from 1936;

- Colorado, individual and corporate, from 1937;

- Maryland, individual and corporate, from 1937;

- District of Columbia, individual and either corporate or franchise, from 1939.

A "mirror" tax is a tax in a U.S. dependency in which the dependency adopts wholesale the U.S. federal income tax code, revising it by substituting the dependency's name for "United States" everywhere, and vice versa. The effect is that residents pay the equivalent of the federal income tax to the dependency, rather than to the U.S. government. Although mirroring formally came to an end with the Tax Reform Act of 1986, it remains the law as seen by the U.S. for Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands because conditions to its termination have not yet been met.[78] In any event, the other mirror tax dependencies (the U.S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa) are free to continue mirroring if, and as much as, they wish.

The U.S. acquired one more dependency from Japan in World War II: the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.

Two states, South Dakota and West Virginia, abolished Depression-era income taxes in 1942 and 1943, but these were nearly the last abolitions. For about twenty years after World War II, new state income taxes appeared at a somewhat slower pace, and most were corporate net income or corporate franchise taxes:[74][75]

- Rhode Island, corporate, from 1947;

- The Territory of Alaska, then Alaska as a state, individual and corporate, from 1949;

- Guam, mirror, from 1950;[79]

- Pennsylvania, corporate, from 1951;

- Oregon removed the restriction of individual income tax funds to property tax relief in 1953;[80]

- Delaware, corporate, from 1958;

- New Jersey, corporate, from 1958;

- Idaho, franchise, from 1959;

- Utah, corporate, from 1959;

- West Virginia, individual, from 1961;

- American Samoa, mirror, from 1963;[81]

- Indiana, individual and corporate, from 1963;

- Wisconsin, franchise, from 1965.

As early as 1957 General Motors protested a proposed corporate income tax in Michigan with threats of moving manufacturing out of the state.[82] However, Michigan led off the most recent group of new income taxes:[75]

- Michigan, individual and corporate (this replacing a value-added tax),[83] from 1967;

- Nebraska, individual and corporate, from 1967;

- Maryland, individual (added county withholding tax and non resident tax. Believes led to state being mainly a commuter state for work) 1967, Present

- West Virginia, corporate, from 1967;

- Connecticut, intangibles (but taxing capital gains and not interest), from 1969;

- Illinois, individual and corporate, from 1969;

- Maine, individual and corporate, from 1969;

- New Hampshire, corporate, from 1970;

- Florida, franchise, from 1971;

- Ohio, individual and corporate, from 1971;

- Pennsylvania, individual, from 1971;

- Rhode Island, individual, from 1971;

- The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, individual and corporate, from 1971.

In the early 1970s, Pennsylvania and Ohio competed for businesses with Ohio wooing industries with a reduced corporate income tax but Pennsylvania warning that Ohio had higher municipal taxes that included taxes on inventories, machinery and equipment.[84]

A few more events of the 1970s follows:[75]

- Michigan abolished its corporate income tax in 1975, replacing it with another value-added tax;[85]

- New Jersey instituted an individual income tax in 1976;

- The Northern Mariana Islands negotiated with the U.S. in 1975 a mirror tax which was to go into effect in 1979, but in 1979 enacted a law rebating that tax partially or entirely each year and levying a simpler income tax;[86][87]

- Alaska abolished its individual income tax retroactive to 1979[88] in 1980.

(Also during this time the U.S. began returning the Panama Canal Zone to Panama in 1979, and self-government, eventually to lead to independence, began between 1979 and 1981 in all parts of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands except for the Northern Mariana Islands. The resulting countries - the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau - all levy income taxes today.)

The only subsequent individual income tax instituted to date is Connecticut's, from 1991, replacing the earlier intangibles tax. The median family income in many of the state's suburbs was nearly twice that of families living in urban areas. Governor Lowell Weicker's administration imposed a personal income tax to address the inequities of the sales tax system, and implemented a program to modify state funding formulas so that urban communities received a larger share.[89]

Numerous states with income taxes have considered measures to abolish those taxes since the Late-2000s recession began, and several states without income taxes have considered measures to institute them, but only one such proposal has been enacted: Michigan replaced its more recent value-added tax with a new corporate income tax in 2009.

Rates by jurisdiction

Alabama

| Individual income tax[90] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Singles/married filing separately | Married filing jointly |

| 2% | $0-$500 | $1000 |

| 4% | $501-$3000 | $1001-$6000 |

| 5% | $3001+ | $6001+ |

The corporate income tax rate is 6.5%.[91]

Alaska

Alaska does not have an individual income tax.[92]

| Corporate income tax[93] | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$24,999 | 0% |

| $25,000-$48,999 | 2% |

| $49,000-$73,999 | $480 plus 3% of income in excess of $49,000 |

| $74,000-$98,999 | $1,230 plus 4% of income in excess of $74,000 |

| $99,000-$123,999 | $2,230 plus 5% of income in excess of $99,000 |

| $124,000-$147,999 | $3,480 plus 6% of income in excess of $124,000 |

| $148,000-$172,999 | $4,920 plus 7% of income in excess of $148,000 |

| $173,000-$197,999 | $6,670 plus 8% of income in excess of $173,000 |

| $198,000-$221,999 | $8,670 plus 9% of income in excess of $198,000 |

| $222,000+ | $10,830 plus 9.4% of income in excess of $222,000 |

Personal income tax

| Single or married & filing separately | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$27,271 | 2.59% |

| $27,272-$54,543 | 3.34% |

| $54,544-$163,631 | 4.17% |

| $163,632+ | 4.5% |

| Married filing jointly or head of household | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$54,543 | 2.59% |

| $54,544-$109,087 | 3.34% |

| $109,088-$327,262 | 4.17% |

| $327,263+ | 4.5% |

Reference:[94]

Corporate income tax

The corporate income tax rate is 4.9%.[95]

Arkansas

| Personal income tax[96] | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate (Eff. 1/1/24) |

| $0-$4,400 | 2% |

| $4,401-$8,800 | 4% |

| $8,801+ | 4.4% |

| Corporate income tax[97] | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate (Eff. 1/1/24) |

| $0-$2,999 | 1% |

| $3,000-$5,999 | 2% |

| $6,000-$10,999 | 3% |

| $11,000+ | 4.8% |

Scheduled Rate Reductions

During a special session of the Arkansas Legislature in September, 2023, the top personal income tax rate was reduced to 4.4% for the year beginning January 1, 2024. The top rate beginning January 1, 2023 had been retroactively reduced to 4.7% during the spring 2023 regular session of the legislature. Previously, during a special session in August, 2022, the top personal income tax rate was reduced to 4.9% retroactively effective to January 1, 2022, instead of 2025 as was originally planned while also marking the first time since 1971 that the top income tax rate has been 5.0% or lower.

California

California taxes all capital gains as income.[98]

Personal income tax

| Single or married filing separately (2021) | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$8,931 | 1% |

| $8,932-$21,174 | 2% |

| $21,175-$33,420 | 4% |

| $33,421-$46,393 | 6% |

| $46,394-$58,633 | 8% |

| $58,634-$299,507 | 9.3% |

| $299,508-$359,406 | 10.3% |

| $359,407-$599,011 | 11.3% |

| $599,012-$999,999 | 12.3% |

| $1,000,000+ | 13.3% |

| Married filing jointly (2021) | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$17,863 | 1% |

| $17,864-$42,349 | 2% |

| $42,350-$66,841 | 4% |

| $66,842-$92,787 | 6% |

| $92,788-$117,267 | 8% |

| $117,268-$599,015 | 9.3% |

| $599,016-$718,813 | 10.3% |

| $718,814-$999,999 | 11.3% |

| $1,000,000-$1,198,023 | 12.3% |

| $1,198,024+ | 13.3% |

| Head of household (not 2021) | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$17,099 | $1% |

| $17,099-$40,512 | $170.99 + 2.00% of the amount over $17,099 |

| $40,512-$52,224 | $639.25 + 4.00% of the amount over $40,512 |

| $52,224-$64,632 | $1,107.73 + 6.00% of the amount over $52,224 |

| $64,632-$76,343 | $1,852.21 + 8.00% of the amount over $64,632 |

| $76,343-$389,627 | $2,789.09 + 9.30% of the amount over $76,343 |

| $389,627-$467,553 | $31,924.50 + 10.30% of the amount over $389,627 |

| $467,553-$779,253 | $39,950.88 + 11.30% of the amount over $467,553 |

| $779,253+ | $75,172.98 + 12.30% of the amount over $779,253 |

| $1,000,000+ | $102,324.86 + 13.30% of the amount over $1,000,000 |

California's listed tax brackets from 1%-12.3% are indexed for inflation and were most recently by 2012 California Proposition 30. There state has a 1% Mental Health Services surtax (Form 540, line 62) for incomes above $1 million that creates the maximum bracket of 13.3%. California also separately imposes a state Alternative Minimum Tax (Form 540, line 52) at a 7% rate, so a taxpayer may end up paying both the AMT and the 1% surtax.

Reference:[99]

Corporate income tax

The standard corporate rate is 8.84%, except for banks and other financial institutions, whose rate is 10.84%.[99]

Colorado

Colorado has a flat rate of 4.55% for both individuals and corporations.[100]

Personal income tax

| Single or married filing separately (2021) | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$9,999 | 3% |

| $10,000-$49,999 | 5% |

| $50,000-$99,999 | 5.5% |

| $100,000-$199,999 | 6% |

| $200,000-$249,999 | 6.5% |

| $250,000-$499,999 | 6.9% |

| $500,000+ | 6.99% |

| Head of household (not 2021) | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$16,000 | 3% |

| $16,001-$80,000 | $480 plus 5% of income in excess of $16,000 |

| $80,001-$160,000 | $3,680 plus 5.5% of income in excess of $80,000 |

| $160,001-$320,000 | $8,080 plus 6% of income in excess of $160,000 |

| $320,001-$400,000 | $17,680 plus 6.5% of income in excess of $320,000 |

| $400,000+ | $22,880 plus 6.7% of income in excess of $400,000 |

| Married filing jointly (2021) | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$19,999 | 3% |

| $20,000-$99,999 | 5% |

| $100,000-$199,999 | 5.5% |

| $200,000-$399,999 | 6% |

| $400,000-$499,999 | 6.5% |

| $500,000-$999,999 | 6.9% |

| $1,000,000+ | 6.99% |

Corporate income tax

Connecticut's corporate income tax rate is 7.5%.[101]

Personal income tax

| Single or married filing separately (2021) | |

|---|---|

| Income Level | Rate |

| $0-$1,999 | 0% |

| $2,000-$4,999 | 2.2% |

| $5,000-$9,999 | 3.9% |

| $10,000-$19,999 | 4.8% |

| $20,000-$24,999 | 5.2% |

| $25,000-$59,999 | 5.55% |

| $60,000+ | 6.6% |

Reference:[102]

Corporate income tax

Delaware's corporate income tax rate is 8.7%.[103]

State individual income tax rates and brackets

| State | Single filer rates > Brackets | Married filing jointly rates > Brackets |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 2.00% > $0 | 2.00% > $0 |

| 4.00% > $500 | 4.00% > $1,000 | |

| 5.00% > $3,000 | 5.00% > $6,000 | |

| Alaska | none | none |

| Arizona | 2.59% > $0 | 2.59% > $0 |

| 3.34% > $27,272 | 3.34% > $54,544 | |

| 4.17% > $54,544 | 4.17% > $109,088 | |

| 4.50% > $163,632 | 4.50% > $327,263 | |

| 8.00% > $250,000 | 8.00% > $500,000 | |

| Arkansas | 2.00% > $0 | 2.00% > $0 |

| 4.00% > $4,300 | 4.00% > $4,300 | |

| 4.90% > $8,500 | 4.90% > $8,500 | |

| California | 1.00% > $0 | 1.00% > $0 |

| 2.00% > $8,932 | 2.00% > $17,864 | |

| 4.00% > $21,175 | 4.00% > $42,350 | |

| 6.00% > $33,421 | 6.00% > $66,842 | |

| 8.00% > $46,394 | 8.00% > $92,788 | |

| 9.30% > $58,634 | 9.30% > $117,268 | |

| 10.30% > $299,508 | 10.30% > $599,016 | |

| 11.30% > $359,407 | 11.30% > $718,814 | |

| 12.30% > $599,012 | 12.30% > $1,000,000 | |

| 13.30% > $1,000,000 | 13.30% > $1,198,024 | |

| Colorado | 4.55% of federal | 4.55% of federal |

| Connecticut | 3.00% > $0 | 3.00% > $0 |

| 5.00% > $10,000 | 5.00% > $20,000 | |

| 5.50% > $50,000 | 5.50% > $100,000 | |

| 6.00% > $100,000 | 6.00% > $200,000 | |

| 6.50% > $200,000 | 6.50% > $400,000 | |

| 6.90% > $250,000 | 6.90% > $500,000 | |

| 6.99% > $500,000 | 6.99% > $1,000,000 | |

| Delaware | 2.20% > $2,000 | 2.20% > $2,000 |

| 3.90% > $5,000 | 3.90% > $5,000 | |

| 4.80% > $10,000 | 4.80% > $10,000 | |

| 5.20% > $20,000 | 5.20% > $20,000 | |

| 5.55% > $25,000 | 5.55% > $25,000 | |

| 6.60% > $60,000 | 6.60% > $60,000 | |

| Florida | none | none |

| Georgia | 1.00% > $0 | 1.00% > $0 |

| 2.00% > $750 | 2.00% > $1,000 | |

| 3.00% > $2,250 | 3.00% > $3,000 | |

| 4.00% > $3,750 | 4.00% > $5,000 | |

| 5.00% > $5,250 | 5.00% > $7,000 | |

| 5.75% > $7,000 | 5.75% > $10,000 | |

| Hawaii | 1.40% > $0 | 1.40% > $0 |

| 3.20% > $2,400 | 3.20% > $4,800 | |

| 5.50% > $4,800 | 5.50% > $9,600 | |

| 6.40% > $9,600 | 6.40% > $19,200 | |

| 6.80% > $14,400 | 6.80% > $28,800 | |

| 7.20% > $19,200 | 7.20% > $38,400 | |

| 7.60% > $24,000 | 7.60% > $48,000 | |

| 7.90% > $36,000 | 7.90% > $72,000 | |

| 8.25% > $48,000 | 8.25% > $96,000 | |

| 9.00% > $150,000 | 9.00% > $300,000 | |

| 10.0% > $175,000 | 10.0% > $350,000 | |

| 11.0% > $200,000 | 11.0% > $400,000 | |

| Idaho | 1.125% > $0 | 1.125% > $0 |

| 3.125% > $1,568 | 3.125% > $3,136 | |

| 3.625% > $3,136 | 3.625% > $6,272 | |

| 4.625% > $4,704 | 4.625% > $9,408 | |

| 5.625% > $6,272 | 5.625% > $12,544 | |

| 6.625% > $7,840 | 6.625% > $15,680 | |

| 6.925% > $11,760 | 6.925% > $23,520 | |

| Illinois | 4.95% > $0 | 4.95% > $0 |

| Indiana | 3.23% > $0 | 3.23% > $0 |

| Iowa | 0.33% > $0 | 0.33% > $0 |

| 0.67% > $1,676 | 0.67% > $1,676 | |

| 2.25% > $3,352 | 2.25% > $3,352 | |

| 4.14% > $6,704 | 4.14% > $6,704 | |

| 5.63% > $15,084 | 5.63% > $15,084 | |

| 5.96% > $25,140 | 5.96% > $25,140 | |

| 6.25% > $33,520 | 6.25% > $33,520 | |

| 7.44% > $50,280 | 7.44% > $50,280 | |

| 8.53% > $75,420 | 8.53% > $75,420 | |

| Kansas | 3.10% > $0 | 3.10% > $0 |

| 5.25% > $15,000 | 5.25% > $30,000 | |

| 5.70% > $30,000 | 5.70% > $60,000 | |

| Kentucky | 5% > $0 | 5% > $0 |

| Louisiana | 2% > $0 | 2% > $0 |

| 4% > $12,500 | 4% > $25,000 | |

| 6% > $50,000 | 6% > $100,000 | |

| Maine | 5.80% > $0 | 5.80% > $0 |

| 6.75% > $22,450 | 6.75% > $44,950 | |

| 7.15% > $53,150 | 7.15% > $106,350 | |

| Maryland | 2.00% > $0 | 2.00% > $0 |

| 3.00% > $1,000 | 3.00% > $1,000 | |

| 4.00% > $2,000 | 4.00% > $2,000 | |

| 4.75% > $3,000 | 4.75% > $3,000 | |

| 5.00% > $100,000 | 5.00% > $150,000 | |

| 5.25% > $125,000 | 5.25% > $175,000 | |

| 5.50% > $150,000 | 5.50% > $225,000 | |

| 5.75% > $250,000 | 5.75% > $300,000 | |

| Massachusetts[105][106] | 5% > $0 | 5% > $0 |

| 9% > $1,000,000 | 9% > $1,000,000 | |

| Michigan | 4.25% > $0 | 4.25% > $0 |

| Minnesota | 5.35% > $0 | 5.35% > $0 |

| 6.80% > $27,230 | 6.80% > $39,810 | |

| 7.85% > $89,440 | 7.85% > $158,140 | |

| 9.85% > $166,040 | 9.85% > $276,200 | |

| Mississippi | 3% > $4,000 | 3% > $4,000 |

| 4% > $5,000 | 4% > $5,000 | |

| 5% > $10,000 | 5% > $10,000 | |

| Missouri | 1.5% > $107 | 1.5% > $107 |

| 2.0% > $1,073 | 2.0% > $1,073 | |

| 2.5% > $2,146 | 2.5% > $2,146 | |

| 3.0% > $3,219 | 3.0% > $3,219 | |

| 3.5% > $4,292 | 3.5% > $4,292 | |

| 4.0% > $5,365 | 4.0% > $5,365 | |

| 4.5% > $6,438 | 4.5% > $6,438 | |

| 5.0% > $7,511 | 5.0% > $7,511 | |

| 5.4% > $8,584 | 5.4% > $8,584 | |

| Montana | 1.0% > $0 | 1.0% > $0 |

| 2.0% > $3,100 | 2.0% > $3,100 | |

| 3.0% > $5,500 | 3.0% > $5,500 | |

| 4.0% > $8,400 | 4.0% > $8,400 | |

| 5.0% > $11,300 | 5.0% > $11,300 | |

| 6.0% > $14,500 | 6.0% > $14,500 | |

| 6.9% > $18,700 | 6.9% > $18,700 | |

| Nebraska | 2.46% > $0 | 2.46% > $0 |

| 3.51% > $3,340 | 3.51% > $6,660 | |

| 5.01% > $19,990 | 5.01% > $39,990 | |

| 6.84% > $32,210 | 6.84% > $64,430 | |

| Nevada | none | none |

| New Hampshire | 4% > $2,400 | 4% > $4,800 |

| Interest & dividends only; reduced 1% per year, ends in 2025 | ||

| New Jersey | 1.400% > $0 | 1.400% > $0 |

| 1.750% > $20,000 | 1.750% > $20,000 | |

| 2.450% > $50,000 | ||

| 3.500% > $35,000 | 3.500% > $70,000 | |

| 5.525% > $40,000 | 5.525% > $80,000 | |

| 6.370% > $75,000 | 6.370% > $150,000 | |

| 8.970% > $500,000 | 8.970% > $500,000 | |

| 10.750% > $1,000,000 | 10.750% > $1,000,000 | |

| New Mexico | 1.70% > $0 | 1.70% > $0 |

| 3.20% > $5,500 | 3.20% > $8,000 | |

| 4.70% > $11,000 | 4.70% > $16,000 | |

| 4.90% > $16,000 | 4.90% > $24,000 | |

| 5.90% > $210,000 | 5.90% > $315,000 | |

| New York | 4.00% > $0 | 4.00% > $0 |

| 4.50% > $8,500 | 4.50% > $17,150 | |

| 5.25% > $11,700 | 5.25% > $23,600 | |

| 5.90% > $13,900 | 5.90% > $27,900 | |

| 5.97% > $21,400 | 5.97% > $43,000 | |

| 6.33% > $80,650 | 6.33% > $161,550 | |

| 6.85% > $215,400 | 6.85% > $323,200 | |

| 8.82% > $1,077,550 | 8.82% > $2,155,350 | |

| North Carolina | 5.25% > $0 | 5.25% > $0 |

| North Dakota | 1.10% > $0 | 1.10% > $0 |

| 2.04% > $40,125 | 2.04% > $67,050 | |

| 2.27% > $97,150 | 2.27% > $161,950 | |

| 2.64% > $202,650 | 2.64% > $246,700 | |

| 2.90% > $440,600 | 2.90% > $440,600 | |

| Ohio | 2.850% > $22,150 | 2.850% > $22,150 |

| 3.326% > $44,250 | 3.326% > $44,250 | |

| 3.802% > $88,450 | 3.802% > $88,450 | |

| 4.413% > $110,650 | 4.413% > $110,650 | |

| 4.797% > $221,300 | 4.797% > $221,300 | |

| Oklahoma | 0.5% > $0 | 0.5% > $0 |

| 1.0% > $1,000 | 1.0% > $2,000 | |

| 2.0% > $2,500 | 2.0% > $5,000 | |

| 3.0% > $3,750 | 3.0% > $7,500 | |

| 4.0% > $4,900 | 4.0% > $9,800 | |

| 5.0% > $7,200 | 5.0% > $12,200 | |

| Oregon | 4.75% > $0 | 4.75% > $0 |

| 6.75% > $3,650 | 6.75% > $7,300 | |

| 8.75% > $9,200 | 8.75% > $18,400 | |

| 9.90% > $125,000 | 9.90% > $250,000 | |

| Pennsylvania | 3.07% > $0 | 3.07% > $0 |

| Rhode Island | 3.75% > $0 | 3.75% > $0 |

| 4.75% > $66,200 | 4.75% > $66,200 | |

| 5.99% > $150,550 | 5.99% > $150,550 | |

| South Carolina | 0.0% > $0 | 0.0% > $0 |

| 3.0% > $3,070 | 3.0% > $3,070 | |

| 4.0% > $6,150 | 4.0% > $6,150 | |

| 5.0% > $9,230 | 5.0% > $9,230 | |

| 6.0% > $12,310 | 6.0% > $12,310 | |

| 7.0% > $15,400 | 7.0% > $15,400 | |

| South Dakota | none | none |

| Tennessee | none | none |

| Texas | none | none |

| Utah | 4.85% > $0 | 4.85% > $0 |

| Vermont | 3.35% > $0 | 3.35% > $0 |

| 6.60% > $40,350 | 6.60% > $67,450 | |

| 7.60% > $97,800 | 7.60% > $163,000 | |

| 8.75% > $204,000 | 8.75% > $248,350 | |

| Virginia | 2.00% > $0 | 2.00% > $0 |

| 3.00% > $3,000 | 3.00% > $3,000 | |

| 5.00% > $5,000 | 5.00% > $5,000 | |

| 5.75% > $17,000 | 5.75% > $17,000 | |

| Washington | none | none |

| West Virginia | 3.00% > $0 | 3.00% > $0 |

| 4.00% > $10,000 | 4.00% > $10,000 | |

| 4.50% > $25,000 | 4.50% > $25,000 | |

| 6.00% > $40,000 | 6.00% > $40,000 | |

| 6.50% > $60,000 | 6.50% > $60,000 | |

| Wisconsin | 3.54% > $0 | 3.54% > $0 |

| 4.65% > $12,120 | 4.65% > $16,160 | |

| 6.27% > $24,250 | 6.27% > $32,330 | |

| 7.65% > $266,930 | 7.65% > $355,910 | |

| Wyoming | none | none |

| Washington, D.C. | 4.00% > $0 | 4.00% > $0 |

| 6.00% > $10,000 | 6.00% > $10,000 | |

| 6.50% > $40,000 | 6.50% > $40,000 | |

| 8.50% > $60,000 | 8.50% > $60,000 | |

| 8.75% > $350,000 | 8.75% > $350,000 | |

| 8.95% > $1,000,000 | 8.95% > $1,000,000 | |

State corporate tax rates and brackets

| State | Brackets |

|---|---|

| Alabama | 6.50% > $0 |

| Alaska | 0.00% > $0 |

| 2.00% > $25,000 | |

| 3.00% > $49,000 | |

| 4.00% > $74,000 | |

| 5.00% > $99,000 | |

| 6.00% > $124,000 | |

| 7.00% > $148,000 | |

| 8.00% > $173,000 | |

| 9.00% > $198,000 | |

| 9.40% > $222,000 | |

| Arizona | 4.90% > $0 |

| Arkansas | 1.00% > $0 |

| 2.00% > $3,000 | |

| 3.00% > $6,000 | |

| 5.00% > $11,000 | |

| 5.30% > $25,000 | |

| California | 8.84% > $0 |

| Colorado | 4.55% > $0 |

| Connecticut | 7.50% > $0 |

| Delaware | 8.70% > $0 |

| Florida | 4.458% > $0 |

| Georgia | 5.75% > $0 |

| Hawaii | 4.40% > $0 |

| 5.40% > $25,000 | |

| 6.40% > $100,000 | |

| Idaho | 6.925% > $0 |

| Illinois | 9.50% > $0 |

| Indiana | 5.25% > $0 |

| Iowa | 5.50% > $0 |

| 9.00% > $100,000 | |

| 9.80% > $250,000 | |

| Kansas | 4.00% > $0 |

| 7.00% > $50,000 | |

| Kentucky | 5.00% > $0 |

| Louisiana | 4.00% > $0 |

| 5.00% > $25,000 | |

| 6.00% > $50,000 | |

| 7.00% > $100,000 | |

| 8.00% > $200,000 | |

| Maine | 3.50% > $0 |

| 7.93% > $350,000 | |

| 8.33% > $1,050,000 | |

| 8.93% > $3,500,000 | |

| Maryland | 8.25% > $0 |

| Massachusetts | 8.00% > $0 |

| Michigan | 6.00% > $0 |

| Minnesota | 9.80% > $0 |

| Mississippi | 3.00% > $4,000 |

| 4.00% > $5,000 | |

| 5.00% > $10,000 | |

| Missouri | 4.00% > $0 |

| Montana | 6.75% > $0 |

| Nebraska | 5.58% > $0 |

| 7.81% > $100,000 | |

| Nevada | Gross Receipts Tax |

| New Hampshire | 7.70% > $0 |

| New Jersey | 6.50% > $0 |

| 7.50% > $50,000 | |

| 9.00% > $100,000 | |

| 11.50% > $1,000,000 | |

| New Mexico | 4.80% > $0 |

| 5.90% > $500,000 | |

| New York | 6.50% > $0 |

| North Carolina | 2.50% > $0 |

| North Dakota | 1.41% > $0 |

| 3.55% > $25,000 | |

| 4.31% > $50,000 | |

| Ohio | Gross Receipts Tax |

| Oklahoma | 6.00% > $0 |

| Oregon | 6.60% > $0 |

| 7.60% > $1,000,000 | |

| Pennsylvania | 9.99% > $0 |

| Rhode Island | 7.00% > $0 |

| South Carolina | 5.00% > $0 |

| South Dakota | None |

| Tennessee | 6.50% > $0 |

| Texas | Gross Receipts Tax |

| Utah | 4.95% > $0 |

| Vermont | 6.00% > $0 |

| 7.00% > $10,000 | |

| 8.50% > $25,000 | |

| Virginia | 6.00% > $0 |

| Washington | Gross Receipts Tax |

| West Virginia | 6.50% > $0 |

| Wisconsin | 7.90% > $0 |

| Wyoming | None |

| Washington, D.C. | 8.25% > $0 |

Other nations

Australia

State governments have not imposed income taxes since World War II.

Between 1915 and 1942, income taxes were levied by both state governments and the federal government. In 1942, to help fund World War II, the federal government took over the raising of all income tax, to the exclusion of the states. The loss of the states' ability to raise revenue by income taxation was offset by federal government grants to the states and, later, the devolution of the power to levy payroll taxes to the states in 1971.[108]

See also

References

- States with no individual income tax are Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas and Wyoming. States with no corporate income tax are Nevada, South Dakota, and Wyoming. For tables of information on state taxes, see, e.g., 2009 State Tax Handbook, CCH, ISBN 9780808019213 (hereafter "CCH") or later editions, or All States Handbook, 2010 Edition, RIA Thomson, ISBN 978-0-7811-0415-9 ("RIA") or later editions.

- Exceptions are Arkansas, Iowa, Mississippi, New Hampshire (interest and dividends only, to be phased out from 2023 and eliminated in 2027), New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, none of which use federal taxable income as a starting point in computing state taxable income. Colorado adjusts federal taxable income only for state income tax, interest on federal obligations, a limited subtraction for pensions, payments to the state college tuition fund, charitable contributions for those claiming the standard deduction, and a few other items of limited applicability. See 2010 Colorado individual income tax booklet Archived 2010-12-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- 31 USC 3124.

- CCH, page 277.

- Carl Davis, Kelly Davis, Matthew Gardner, Robert S. McIntyre, Jeff McLynch, Alla Sapozhnikova, "Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States" Archived 2012-05-15 at the Wayback Machine, Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy, Third Edition, November 2009, pp 118.

- "Request Rejected" (PDF). revenuefiles.delaware.gov. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- "States That Allow You to Deduct Federal Income Taxes". The Balance. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- "Publications". Ohio Department of Taxation. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

Since 1975, the department has published a Brief Summary of Major State & Local Taxes in Ohio, designed to be a quick overview of all of the state's significant state and local taxes.

- Alaska Permanent Fund Division website eligibility requirements www.PFD.state.AK.us/eligibility Archived 2011-09-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Florida Dept. Of Revenue - Florida Dept. Of Revenue" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- "FL Dept Rev - Florida's Corporate Income Tax". Dor.myflorida.com. 2013-01-01. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- "FL Dept Rev - 2007 Tax Information Publication #07C02-01". Dor.myflorida.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- Insider Viewpoint of Las Vegas, Las Vegas, Nevada USA (2009-07-01). "Taxes - Las Vegas - Nevada". Insidervlv.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bankrate.com. "Nevada". Bankrate.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-02. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- N.H. House Bill 2 of 2023

- NH Department of Revenue Administration. "Overview of New Hampshire Taxes". www.revenue.nh.gov. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- "South Dakota Department of Revenue". Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- "Tennessee Income Tax Prohibition, Amendment 3 (2014)". Ballotpedia. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- "Texas Proposition 4, Prohibit State Income Tax on Individuals Amendment (2019)". Ballotpedia. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- Business and Occupation Archived 2007-04-28 at the Wayback Machine, Washington State Department of Revenue

- Business and Occupation Tax brochure Archived 2008-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, Washington State Department of Revenue (2007)

- "Seattle City Council approves income tax on the rich, but quick legal challenge likely". The Seattle Times. July 10, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- "Seattle's income tax on the wealthy is illegal, judge rules". The Seattle Times. November 22, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- "State Court of Appeals rules Seattle's wealth tax is unconstitutional, but gives cities new leeway". The Seattle Times. July 15, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- "Washington state Supreme Court denies Seattle's bid for income tax on wealthy households". The Seattle Times. April 3, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- "Washington State Legislature". app.leg.wa.gov. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- Jinkins, Laurie (2019-12-19). "First in the Nation: Washington State's Long-Term Care Trust Act". The Milbank Quarterly. 98 (1): 10–13. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12439. PMC 7077770. PMID 31856332. Archived from the original on 2021-05-16.

- "Wyoming Department of Revenue". revenue.state.wy.us. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "State Individual Income Taxes" (PDF). taxadmin.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Indiana Growth Model Archived 2017-02-24 at the Wayback Machine. Wall Street Journal (2016-07-20). Retrieved on 2016-08-09.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "USA Income Tax Rates 2016 Federal and State Tax". www.scopulus.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-01-16. Retrieved 2013-01-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "What cities impose an income tax?". Michigan.gov. 2013-02-21. Archived from the original on 2013-05-26. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- "Tax Rates". Pennsylvania Department of Revenue. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- "Wage Tax (employers) | Services". City of Philadelphia. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- "Municipal Statistics". munstats.pa.gov. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- "Local Withholding Tax FAQs". PA Department of Community & Economic Development. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- "RITA Municipalities - Regional Income Tax Agency". www.ritaohio.com. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- Mervosh, Sarah (November 26, 2019). "They Wanted to Save Their 119-Year-Old Village. So They Got Rid of It". The New York Times. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- Texas Statutes Chapter 171 Archived 2010-07-26 at the Wayback Machine Section 171.101. CCH State Tax Handbook 2009 edition, page 219. 2009 edition ISBN 9780808019213

- Accounts, Texas Comptroller of Public. "Franchise Tax". www.window.state.tx.us. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Complete Auto Transit, Inc. v. Brady, 430 U.S. 274, 279 (1977)

- Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298, 314 (1992)

- National Bellas Hess v. Illinois, 386 U.S. 753 (1967)

- See, e.g., Tax Commissioner of the State of West Virginia v. MBNA America Bank, 220 W. Va. 163, 640 S.E.2d 226, 231 (2006), cert. denied, 551 U.S. 1141.

- See, generally, MBNA, supra, and Geoffrey, Inc. v. South Carolina Tax Commission, 313 S.C. 15, 437 S.E.2d 13

- See, e.g., the discussion in Hellerstein, Hellerstein & Youngman, State and Local Taxation, Chapter 8 section C. ISBN 0-314-15376-4.

- For a compilation of formulas, see State Tax Handbook published annually by CCH.

- Nadia Ahmad (October 25, 2021). "2021 Capital Gains Tax Rates by State". Yahoo!. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- Seligman, Edwin R.A. (1914). The Income Tax: A Study of the History, Theory, and Practice of Income Taxation at Home and Abroad. Second edition, revised and enlarged with a new chapter. New York: The Macmillan Company. Underlies most of the history section through 1911, although several examples of sloppiness are recorded below, but for the faculty taxes and Seligman's evaluation of them as income taxes, see Part II Chapter I, pp. 367-387.

- Rabushka, Alvin (2008). Taxation in Colonial America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13345-4

- Becker, Robert A. (1980). Revolution, Reform, and the Politics of American Taxation, 1763-1783. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-0654-2

- Kinsman, Delos Oscar (1900). The Income Tax in the Commonwealths of the United States. Ithaca: Publications of the American Economic Association, Third Series, Vol. IV, No. 4. A source for the history section through 1900 in general, but specifically for the Virginia faculty tax see pp. 13-14. The tax from 1786 to 1790 referred to by Seligman, p. 380, is simply a tax on court clerks also mentioned by Kinsman, and as a tax on a single occupation is not listed here. Later writers have typically followed Seligman, but the tax referred to by Kinsman is in fact reported in the sources he cites, Hennings' Statutes at Large, volumes IX pp. 350, 353-354, and 548, and amended out of existence where he says, Hennings volume XI p. 112. For the 1786-1790 tax see Hennings volume XII pp. 283-284 and repeal in volume XIII p. 114

- Kinsman, pp. 31-32.

- Seligman, p. 402

- Comstock, Alzada (1921). State Taxation of Personal Incomes. Volume CI, Number 1, or Whole Number 229, of Studies in History, Economics and Public Law edited by the Faculty of Political Science of Columbia University. New York: Columbia University. On the Panic of 1837 see p. 14.

- Seligman, pp. 406-414.

- Kinsman, p. 102; the date 1860 reported by Seligman, p. 413, is clearly a typo, since the two writers use the same reference, the Texas Laws of 1863, chapter 33, section 3.

- Kinsman, p. 100; Seligman, p. 413, says 1864, but the common reference, the Louisiana Laws of 1864 act 55 section 3, is in fact to Laws of 1864-1865, and this law was enacted in April 1865.

- Kinsman, p. 98

- Comstock, pp. 18-26

- State Taxation of Interstate Commerce. Report of the Special Subcommittee on State Taxation of Interstate Commerce of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives. Pursuant to Public Law 86-272, as Amended. 88th Congress, 2d Session, House Report No. 1480, volume 1. (Usually abbreviated House Report 88-1480.) Often referred to as the "Willis committee report" after chair Edwin E. Willis. See p. 99.

- Comstock generally.

- National Industrial Conference Board, Inc. (1930). State Income Taxes. Volume I. Historical Development. New York.

- Stark, John O. (1987-1988). "The Establishment of Wisconsin's Income Tax". Wisconsin Magazine of History Archived 2006-11-30 at the Wayback Machine volume 71 pp. 27-45.

- Foster, Roger (1915). A Treatise on the Federal Income Tax under the Act of 1913. Second edition. Rochester, N.Y.: The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Co. Pp. 889-894.

- Legislative Interim Tax Study Committee (1958). Development of State Income Taxes in the United States and Oregon. Salem, OR. Pp. 21-22.

- Rowe, L[eo] S. (1904). The United States and Porto Rico. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., but seen as New York: Arno Press, 1975, ISBN 0-405-06235-4. Pp. 188-190.

- Tantuico, Francisco Sr., and Francisco Tantuico Jr. (1961). Rules and Rulings on the Philippine Income Tax. Tacloban: The Leyte Publishing Corp. Pp. 3-5.

- Clark, Victor S., et alii (1930). Porto Rico and Its Problems. Washington: The Brookings Institution. P. 200.

- Chyatte, Scott G. (1988). "Taxation through the Looking Glass: The Mirror Theory and the Income Tax System of the U.S. Virgin Islands before and after the Tax Reform Act of 1986". Pp. 170-205 of Volume 6, Issue 1 of Berkeley Journal of International Law Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine. Pp. 173-176.

- Blakey, Roy G., and Violet Johnson (1942). State Income Taxes. New York: Commerce Clearing House. List pp.3-4.

- Penniman, Clara, and Walter W. Heller (1959). State Income Tax Administration. Chicago: Public Administration Service. Chart pp. 7-8.

- Penniman, Clara (1980). State Income Taxation. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2290-4. Chart pp. 2-3.

- Legislative Interim Tax Study Committee, pp. 24-28.

- Washington State Research Council (1964). A State Income Tax: pro & con. Pp. 6-7.

- Joint Committee on Taxation (2012). Federal Tax Law and Issues Related to the United States Territories. JCX-41-12. Pp. 8, 20, and 22.

- Leiserowitz, Bruce (1983). "Coordination of Taxation between the United States and Guam". Pp. 218-229 of Volume 1, Issue 1 of Berkeley Journal of International Law Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine. Pp. 219-222.

- Legislative Interim Tax Study Committee, pp. 35-36.

- Department of the Treasury (1979). Territorial Income Tax Systems: Income Taxation in the Virgin Islands, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and American Samoa. Washington. P. 28.

- "GM warns Michigan", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Pittsburgh, PA, April 30, 1957

- House Fiscal Agency (2003). Background and History: Michigan's Single Business Tax. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed 22nd November 2013, p. 5 - McConnell, Dave (February 27, 1970), "Look before you leap, C of C says", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Pittsburgh, PA

- House Fiscal Agency, p. 6

- Department of the Treasury 1979 pp. 26-27.

- Joint Committee on Taxation 2012 p. 22.

- Tax Division, Department of Revenue, State of Alaska (2012). Annual Report Fiscal Year 2012. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-09-22. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed 22nd November 2013. P. 84. - "Connecticut - History". City-data.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- "Tax Foundation State Individual Income Tax Rates" (PDF). 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "State Corporate Income Tax Rates" (PDF). Tax Foundation. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "Personal Income" (PDF). Tax Foundation. Tax Foundation. 2021. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- AS 43.20.011

- "Section 43-1011. Taxes and tax rates". Arizona Revised Statutes. Phoenix: Arizona Legislature. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Janelle Cammenga (February 2021). "State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2021" (PDF). Tax Foundation. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "Personal Income Tax Rates in Arkansas | AEDC".

- "Corporate Income Tax Rates in Arkansas | AEDC".

- "What Are Capital Gains Taxes for the State of California?". Forbes.

- "2018 California Tax Rates and Brackets". California Franchise Tax Board. 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-09-08. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- "Colorado" (PDF). Tax Foundation. Tax Foundation. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Janelle Cammenga (2015). "Title 12 | Chapter 208 - Corporation Business Tax". General Statutes of Connecticut (PDF). Hartford: Connecticut General Assembly. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2021" (PDF). TaxFoundation.org. 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- "State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2021" (PDF). TaxFoundation.org. 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- "State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2021 - Tax Foundation" (PDF). taxfoundation.org. 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "USA Income Tax Rates 2016 Federal and State Tax". www.scopulus.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Massachusetts taxes "unearned income" at 12%; some categories allow a 50% deduction, producing an effective rate of 6%. See Individual Income Tax Provisions in the States Archived 2009-11-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- "State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2021 - Tax Foundation" (PDF). taxfoundation.org. 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Reinhardt, Sam; Steel, Lee (15 June 2006). "Economic Roundup Winter 2006: A brief history of Australia's tax system". Australian Government | The Treasury.

External links

- Federation of Tax Administrators: State Tax Agencies

- Who Pays? (2009 edition)

- A Critique of Who Pays, 6th ed., 2018.