Splenectomy

A splenectomy is the surgical procedure that partially or completely removes the spleen. The spleen is an important organ in regard to immunological function due to its ability to efficiently destroy encapsulated bacteria. Therefore, removal of the spleen runs the risk of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection, a medical emergency and rapidly fatal disease caused by the inability of the body's immune system to properly fight infection following splenectomy or asplenia.[1]

| Splenectomy | |

|---|---|

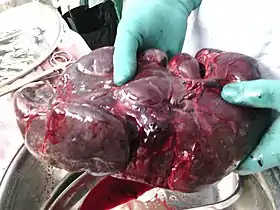

Surgically removed spleen of a child with thalassemia. It is about 15 times larger than normal. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 41.43, 41.5 |

| MeSH | D013156 |

| OPS-301 code | 5-413 |

Common indications for splenectomy include trauma, tumors, splenomegaly or for hematological disease such as sickle cell anemia or thalassemia.[2]

Indications

The spleen is an organ located in the abdomen next to the stomach. It is composed of red pulp which filters the blood, removing foreign material, damaged and worn out red blood cells. It also functions as a storage site for iron, red blood cells and platelets. The rest (~25%) of the spleen is known as the white pulp and functions like a large lymph node being the largest secondary lymphoid organ in the body.[3] Apart from regular lymphatic function the white pulp contains splenic macrophages which are particularly good at destroying (phagocytosis) encapsulated bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae.[4] The spleen is also known to function as a site for the development of new red blood cells from their hematopoietic stem cell precursors, and particularly in situations in which the bone marrow, the normal site for this process, has been compromised by a disorder such as leukemia. The spleen is enlarged in a variety of conditions such as malaria, mononucleosis and most commonly in cancers of the lymphatics, such as lymphomas or leukemia.

It is removed under the following circumstances:

- When it becomes very large such that it becomes destructive to platelets/red blood cells or rupture is imminent

- For diagnosing certain lymphomas

- Certain cases of splenic abscess

- Certain cases of wandering spleen

- Splenic vein thrombosis with bleeding Gastric varices

- When platelets are destroyed in the spleen as a result of an auto-immune condition, such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

- When the spleen bleeds following physical trauma

- Following spontaneous rupture

- For long-term treatment of congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP) if severe hemolytic anemia develops[5]

- The spread of gastric cancer to splenic tissue

- When using the splenic artery for kidney revascularisation in renovascular hypertension.

- For long-term treatment of congenital pyruvate kinase (PK) deficiency

- Those who have a severe version of the hereditary blood disorder Spherocytosis.

- During surgical resection of a pancreatic cancer

The classical cause of traumatic damage to the spleen is a blow to the abdomen during a sporting event. In cases where the spleen is enlarged due to illness (mononucleosis), trivial activities, such as leaning over a counter or straining while defecating, can cause a rupture.

Procedure

Laparoscopy is the preferred procedure in cases where the spleen is not too large and when the procedure is elective. Open surgery is performed in trauma cases or if the spleen is enlarged. Either method is major surgery and is performed under general anesthesia. Vaccination for S. pneumoniae, H. influenza and N. meningitidis should be given pre-operatively if possible to minimize the chance of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI), a rapid-developing and highly fatal type of septicaemia. The spleen is located and disconnected from its arteries. The ligaments holding the spleen in place, gastrosplenic ligament, splenorenal ligament and splenocolic ligament, are dissected and the organ is removed. In some cases, one or more accessory spleens are discovered and also removed during surgery. The incisions are closed and when indicated, a drain is left. If necessary, tissue samples are sent to a laboratory for analysis.

Side effects

Splenectomy causes an increased risk of sepsis, particularly overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis due to encapsulated organisms such as S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae which are no longer able to be destroyed.[4] It has been found that the risk of acquiring sepsis is 10 to 20 times higher in a splenectomized patient compared to a non-splenectomized patient, which can result in death, especially in young children.[6] Therefore, patients are administered the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (Prevnar), Hib vaccine, and the meningococcal vaccine post-operatively (see asplenia). These bacteria often cause a sore throat under normal circumstances but after splenectomy, when infecting bacteria cannot be adequately opsonized, the infection becomes more severe.

Splenectomy also increases the severity of babesiosis, Splenectomized patients are more susceptible to contracting babesiosis and can die within five to eight days of symptom onset.[7] They have severe hemolytic anemia, and occasional hepatomegaly has been documented. Parasitemia levels can reach up to 85% in patients without spleens, compared to 1–10% in individuals with spleens and effective immune systems.[8]

An increase in blood leukocytes can occur following a splenectomy.[9] The post-splenectomy platelet count may rise to abnormally high levels (thrombocytosis), leading to an increased risk of potentially fatal clot formation. Mild thrombocytosis may be observed after a splenectomy due to the lack of sequestering and destruction of platelets that would normally be carried out by the spleen. In addition, the splenectomy may result in a slight increase in the production of platelets within the bone marrow. Normally, erythrocytes are stored and removed from the circulating blood by the spleen, including the removal of damaged erythrocytes. However, after a splenectomy the lack of presence of the spleen means this function cannot be carried out so damaged erythrocytes will continue to circulate in the blood and can release substances into the blood. If these damaged erythrocytes have a procoagulant activity then the substances they release can lead to the development of a procoagulant state and this can cause thromboembolic events e.g. pulmonary embolism, portal vein thrombosis and deep vein thrombosis.[6] There also is some conjecture that post-splenectomy patients may be at elevated risk of subsequently developing diabetes.[10] Splenectomy may also lead to chronic neutrophilia. Splenectomy patients typically have Howell-Jolly bodies[11][12] and less commonly Heinz bodies in their blood smears.[13] Heinz bodies are usually found in cases of G6PD (Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase) and chronic liver disease.[14]

A splenectomy also results in a greatly diminished frequency of memory B cells.[15] A 28-year follow-up of 740 World War II veterans who had their spleens removed on the battlefield showed a significant increase in the usual death from pneumonia (6 deaths rather than the expected 1.74) and an increase in the deaths from ischemic heart disease (41 deaths rather than the expected 30.26) but not from other conditions.[16]

Subtotal splenectomy

Much of the spleen's protective roles can be maintained if a small amount of spleen can be left behind.[17] Where clinically appropriate, attempts are now often made to perform either surgical subtotal (partial) splenectomy,[18] or partial splenic embolization.[19] In particular, whilst vaccination and antibiotics provide good protection against the risks of asplenia, this is not always available in poorer countries.[20] However, as it may take some time for the preserved splenic tissue to provide the full protection, it has been advised that preoperative vaccination still be given.[21]

See also

References

- Taniguchi, Leandro Utino; Correia, Mário Diego Teles; Zampieri, Fernando Godinho (December 2014). "Overwhelming post-splenectomy infection: narrative review of the literature". Surgical Infections. 15 (6): 686–693. doi:10.1089/sur.2013.051. ISSN 1557-8674. PMID 25318011.

- Weledji, Elroy P. (2014). "Benefits and risks of splenectomy". International Journal of Surgery (London, England). 12 (2): 113–119. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.11.017. ISSN 1743-9159. PMID 24316283.

- Cesta, Mark F. (2006). "Normal structure, function, and histology of the spleen". Toxicologic Pathology. 34 (5): 455–465. doi:10.1080/01926230600867743. ISSN 0192-6233. PMID 17067939. S2CID 39791978.

- Di Sabatino, Antonio; Carsetti, Rita; Corazza, Gino Roberto (2011-07-02). "Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states". Lancet. 378 (9785): 86–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61493-6. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 21474172. S2CID 30554953.

- Frye R. (2006-03-02). "Porphyria, Cutaneous". eMedicine. Retrieved 2006-03-28.

- Tarantino G, Scalera A, Finelli C (June 2013). "Liver-spleen axis: intersection between immunity, infections and metabolism". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (23): 3534–42. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3534. PMC 3691032. PMID 23801854.

- "Babesiosis". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. 2009-02-19. Archived from the original on 2009-03-05.

- Gelfand, Jeffrey A.; Vannier, Edouard (6 March 2008). "Ch. 204: Babesiosis". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 17e. McGraw-Hill's Access Medicine. ISBN 978-0071466332.

- Working Party of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology Clinical Haematology Task Force (February 1996). "Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of infection in patients with an absent or dysfunctional spleen". BMJ. 312 (7028): 430–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7028.430. PMC 2350106. PMID 8601117.

- Kolata G (9 November 2004). "A Diabetes Researcher Forges Her Own Path to a Cure". The New York Times.

- synd/1596 at Who Named It?

- Katcher AL (Mar 1980). "Familial asplenia, other malformations, and sudden death". Pediatrics. 65 (3): 633–5. doi:10.1542/peds.65.3.633. PMID 7360556. S2CID 25109676.

- Rodak B, Fritsma G, Doig K. Hematology: Clinical Principles and Applications.

- Irwin JJ, Kirchner JT (October 2001). "Anemia in children". American Family Physician. 64 (8): 1379–86. PMID 11681780.

- Kruetzmann S, Rosado MM, Weber H, Germing U, Tournilhac O, Peter HH, Berner R, Peters A, Boehm T, Plebani A, Quinti I, Carsetti R (April 2003). "Human immunoglobulin M memory B cells controlling Streptococcus pneumoniae infections are generated in the spleen". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 197 (7): 939–45. doi:10.1084/jem.20022020. PMC 2193885. PMID 12682112.

- Robinette CD, Fraumeni JF (July 1977). "Splenectomy and subsequent mortality in veterans of the 1939-45 war". Lancet. 2 (8029): 127–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(77)90132-5. PMID 69206. S2CID 38605411.

- Grosfeld JL, Ranochak JE (June 1976). "Are hemisplenectomy and/or primary splenic repair feasible?". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 11 (3): 419–24. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(76)80198-4. PMID 957066.

- Bader-Meunier B, Gauthier F, Archambaud F, Cynober T, Miélot F, Dommergues JP, Warszawski J, Mohandas N, Tchernia G (January 2001). "Long-term evaluation of the beneficial effect of subtotal splenectomy for management of hereditary spherocytosis". Blood. 97 (2): 399–403. doi:10.1182/blood.V97.2.399. PMID 11154215. S2CID 22741973.

- Pratl B, Benesch M, Lackner H, Portugaller HR, Pusswald B, Sovinz P, Schwinger W, Moser A, Urban C (January 2008). "Partial splenic embolization in children with hereditary spherocytosis". European Journal of Haematology. 80 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00979.x. PMID 18028435. S2CID 41343243.

- Sheikha AK, Salih ZT, Kasnazan KH, Khoshnaw MK, Al-Maliki T, Al-Azraqi TA, Zafer MH (October 2007). "Prevention of overwhelming postsplenectomy infection in thalassemia patients by partial rather than total splenectomy". Canadian Journal of Surgery. 50 (5): 382–6. PMC 2386178. PMID 18031639.

- Kimber C, Spitz L, Drake D, Kiely E, Westaby S, Cozzi F, Pierro A (June 1998). "Elective partial splenectomy in childhood". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 33 (6): 826–9. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(98)90651-0. PMID 9660206.