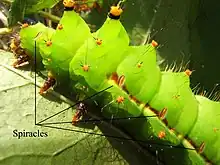

Spiracle (arthropods)

A spiracle or stigma is the opening in the exoskeletons of insects, myriapods, velvet worms and some spiders to allow air to enter the trachea.[1][2][3] In the respiratory system of insects, the tracheal tubes primarily deliver oxygen directly into the animals' tissues. In most species the spiracles can be opened and closed in an efficient manner to admit air while reducing water loss. In various species, this is done by a wide range of mechanisms, such as elastic closure, and closer muscles surrounding the spiracle or kinking the tube. In some the muscle relaxes to open the spiracle, in others to close it. [4] The closer muscle is controlled by the central nervous system, but can also react to localized chemical stimuli. Several aquatic insects have similar or alternative closing methods to prevent water from entering the trachea. The timing and duration of spiracle closures can affect the respiratory rates of the organism.[5] Spiracles may also be surrounded by hairs to minimize bulk air movement around the opening, and thus minimize water loss.

Most myriapods have paired lateral spiracles similar to those of insects. Scutigeromorph centipedes are an exception, having unpaired, non-closable spiracles at the posterior edges of tergites.[2]

Velvet worms have tiny spiracles scattered over the surface of the body and linked to unbranched tracheae. There can be as many as 75 spiracles on a body segment. They are most abundant on the dorsal surface. They cannot be closed, which means velvet worms easily lose water and thus are restricted to living in humid habitats.[3]

Although all insects have spiracles, only some spiders have them, such as orb weavers and wolf spiders. Ancestrally, spiders have book lungs, not trachea. However, some spiders evolved a tracheal system independently of the tracheal system in insects, which includes independent evolution of the spiracles as well. These spiders retained their book lungs, however, so they have both.[6][7]

Literature

- Chapman, R.F. (1998): The Insects, Cambridge University Press

References

- Solomon, Eldra, Linda Berg, Diana Martin (2002): Biology. Brooks/Cole

- Hilken, Gero; Rosenberg, Jörg; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Blüml, Valentin; Hammel, Jörg U.; Hasenberg, Anja; Sombke, Andy (2021). "The tracheal system of scutigeromorph centipedes and the evolution of respiratory systems of myriapods". Arthropod Structure & Development. 60: 101006. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2020.101006. PMID 33246291. S2CID 227191511.

- "Untitled 1". lanwebs.lander.edu. Retrieved 2023-02-06.

- Imms' General Textbook of Entomology: Volume 1: Structure, Physiology and Development Volume 2: Classification and Biology. Berlin: Springer. 1977. ISBN 0-412-61390-5.

- Wilmer, Pat, Graham Stone, and Ian Johnston (2005). Environmental Physiology of Animals. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 171–172. ISBN 9781405107242.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "How Do Spiders Breathe?". Sciencing. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

- Schmitz, Anke (May 2016). "Respiration in spiders (Araneae)". Journal of Comparative Physiology B: Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology. 186 (4): 403–415. doi:10.1007/s00360-016-0962-8. ISSN 1432-136X. PMID 26820263. S2CID 16863495.