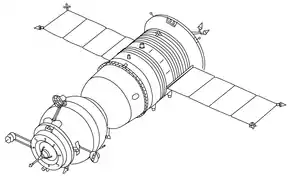

Soyuz-TM

The Soyuz-TM were fourth generation (1986–2002) Soyuz spacecraft used for ferry flights to the Mir and ISS space stations. The Soyuz spacecraft consisted of three parts, the Orbital Module, the Descent Module and the Service Module.[1]

Soyuz-TM spacecraft. | |

| Manufacturer | Korolev |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Soviet Union and Russia |

| Operator | Soviet space program/Russian Federal Space Agency |

| Applications | Carry three cosmonauts to Mir and ISS and back |

| Specifications | |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Design life | Up to six months docked to station |

| Production | |

| Status | Out of service |

| Launched | 34 |

| Maiden launch | Soyuz TM-1, 1986 |

| Last launch | Soyuz TM-34, 2002 |

| Related spacecraft | |

| Derived from | Soyuz-T |

| Derivatives | Soyuz-TMA |

The first launch of the spacecraft was the uncrewed Soyuz TM-1 on May 21, 1986, where it docked with the Mir space station.[2] The final flight was Soyuz TM-34, which docked with the International Space Station and landed November 10, 2002.[3]

Background

After the Apollo-Soyuz Test project in 1976, the Soyuz for crewed flights had the singular mission of supporting crewed space stations.[4] The original Soyuz had a limited endurance when docked with a station, only about 60 to 90 days.[4] There were two avenues for extending the duration of missions past this. The first avenue was to make upgrades to increase the Soyuz spacecraft's endurance. The Soyuz-T could last 120 days and the Soyuz-TM could last 180 days.[4] The other was to use a Visiting Expedition to fly a new Soyuz up to the station and depart with the spacecraft nearing the end of its rated endurance.[4]

The preliminary design was released in April 1981 and the main set of working documentation was released in early 1982.[5]

Upgrades from Soyuz-T

The Soyuz-TM was an upgraded version of the Soyuz-T. The TM stood for transport modified (or транспортный модифицированный in Russian).[2]

Orbital Module

With the growth of orbital complexes, the Soyuz-T used the Igla system that required continuous orientation with the station and had high fuel costs. The Soyuz-TM was upgraded with the Kurs system that did not require the same orientation from the station and allowed measurements from a range of 200 km instead of the 30 km of the Igla.[6]

Descent Module

It also increased the payload to 51.6° orbit by 200–250 kg and was able to return 70–90 kg more back to earth. Energia accomplished this by increasing the capabilities of the launch vehicle and decreasing the mass of the ship.[6] The parachute system mass was decreased by 120 kg (40%) by using synthetic material for the slings and lightweight material for the parachute domes.[6]

Propulsion/Service Module

It also featured a new KTDU-80 propulsion module that permitted the Soyuz-TM to maneuver independently of the station, without the station making "mirror image" maneuvers to match unwanted translations introduced by earlier models' aft-mounted attitude control. It also used the baffles inside the tanks became structural, allowing further reduction in mass.

Typical Flight for Soyuz-TM

Training

.jpg.webp)

Classroom training is completed on Soyuz systems and required crew operations. Cosmonauts must pass an oral test on the material for certification. Training was also completed on Soyuz mockups and simulators. Two weeks before launch, after passing all the tests, the crew is flown to Baikonur to participate in a test at the launch site to go through all the steps associated with the launch.[7]

For Flight Readiness

The final decision to launch is made by the assembly company (General Designer).[8] There is a Space Committee formed of approximately 20 people headed by a 3-star General for Air and Space with the following representation:

- RSA

- NPO-Energia

- General Designer

- Central Institute of Machine Building

- Ministry of Defense

- Physicians

- Baikonur

When different companies/countries are involved, they are represented as well at on the Space Committee. For Soyuz launches, the Ministry of Defense representative states that everything has been checked because all preparations at Baikonur are performed by the military. Independent assessment is made by the Central Institute of Machine Building for every flight.[8] Cosmonauts had to get clearance from the Russian Medical Commission, the Institute of Biomedical Problems and the GCTC at the flight readiness Review.[8]

Table of Flights

Gallery

External links

- RSC Energia: Concept Of Russian Manned Space Navigation Development

- Mir Hardware Heritage

- David S.F. Portree, Mir Hardware Heritage, NASA RP-1357, 1995

- Mir Hardware Heritage (wikisource)

- Information on Soyuz spacecraft

- OMWorld's ASTP Docking Trainer Page

- NASA - Russian Soyuz TMA Spacecraft Details

- Space Adventures circum-lunar mission - details

References

- Miller, Denise (30 July 2013). "What is the Soyzu Spacecraft". nasa.gov.

- Portree, David S. (1995). Mir Hardware Heritage (PDF). NASA. pp. 53–59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-07-09.

- "Soyuz ISS Missions" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-02.

- Portree, David S. (1995). Mir Hardware Heritage. NASA. pp. 6–7.

- "Soyuz TM (7K-STM) spacecraft". gctc.ru.

- "Soyuz TM manned transport spacecraft". energia.ru.

- OSMA Assessments Team. "NASA Astronauts on Soyuz: Experience and Lessons for the Future" (PDF). sma.nasa.gov.

- OSMA Assessments Team (2010). NASA Astronauts on Soyuz: Experience and Lessons for the Future (PDF). NASA. pp. 12–13.