Atlantic humpback dolphin

The Atlantic humpback dolphin (Sousa teuszii) is a species of humpback dolphin that is found in coastal areas of West Africa.

| Atlantic humpback dolphin | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Sousa |

| Species: | S. teuszii |

| Binomial name | |

| Sousa teuszii (Kükenthal, 1892) | |

| |

| Range of Atlantic humpback dolphin | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Sotalia teuszii Kükenthal, 1892 | |

It is regarded as critically endangered by the IUCN.[1]

Description

Apart from its geographical range, it can be distinguishable from the Indo-Pacific humpback because of their distinct skin coloration and other morphological characteristics. Atlantic humpbacks have a gray or white color, unlike the Indo-Pacific humpbacks which have pink mottling.[3] Males, in particular, can have distinct humps under their dorsal fins.[3] They can also be distinguished by a robust body with a well-defined rostrum. They are typically slate gray on the back and sides, fading to light gray ventrally. The dorsal fin is small, slightly falcate, and triangular, and sits on a distinctive and well developed dorsal hump.

Atlantic humpbacks can also be distinguishable from the other species (S. plumbea, S. chinensis, S. sahulensis sp. nov., etc.) because of a significantly lower amount of teeth. On average, they have about 30 teeth per row versus other species having around 33–37. To compliment this, they typically have a shorter and wider skull than the other species.[4]

At birth, this species is 14 kg (31 lb) in weight and 100 cm (39 in) long.[3] A fully grown male can weigh up to 280 kg (620 lb) and is around 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in) long[3]

Range and habitat

This species is native to the tropical to subtropical west coast of Africa in the southeastern Atlantic Ocean, from western Sahara to Angola. The species is not commonly observed and is found sporadically across these waters.[1] It is mainly found in shallow coastal and estuarine waters in the marine Neritic zone, usually less than 20 m (66 ft) deep.[1][5]

Behavior and diet

This species is known to be shy; it does not bow-ride and aerial displays are rarely seen. They occasionally leap, spy-hop, and tail-slap the water. Atlantic humpback dolphins prefer to keep a distance from boat engines, and when they are seen in the water, they are most likely traveling and foraging. They forage both independently and cooperatively.[6] The groups usually range from 1-8 animals, but gatherings of up to 20-40 animals have been observed. An average swim speed during travel has been measured at about 4 km/h (2.5 mph).[7] In Angola and Guinea, some individuals appear to exhibit high site fidelity and strong association patterns.[5] Atlantic humpback dolphins communicate similarly to other dolphin species via echolocation.[6]

Groups generally forage close to shore in shallow waters and often within the surf zone. They appear to feed mainly on inshore schooling fish such as mullet, though a variety of coastal fish and crustacean species are also known as their prey items. Their specific prey species depends on what geographic location they occupy and what is available.[6] These dolphins tend to feed in small bays, sheltered waters behind reef-breaks and in areas off dry river mouths, while traveling occurs mainly along exposed coastlines.[5]

Interaction with humans

The Atlantic humpback dolphin is known to engage in cooperative fishing with Mauritanian Imraguen fishermen, by driving fish towards the shore and into their nets.[8] Incidental capture in gill nets is considered their greatest threat followed by directed takes, habitat loss and degradation, overfishing, marine pollution, anthropogenic sound, and climate change.[5]

Threats

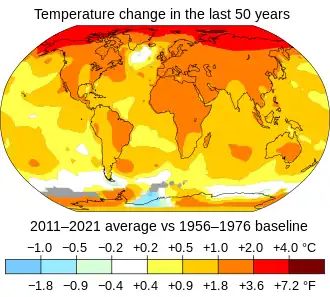

Habitat loss and degradation are the measured causes of declines in the Atlantic humpback dolphin population.[9] Humans are continuously expanding coastal communities and polluting the oceans, which cause a threat to marine life. Overfishing reduces the number of prey available to the dolphins, which leads to an inadequate amount of diet available to them. They are vulnerable to marine pollution (oil spills, untreated sewage, run-off from agricultural areas, etc.) and subsequent marine bacterial bloom, which causes harm to coastal cetaceans. Toxins from the bacteria in the water can easily wipe out a critically endangered species, like the Atlantic Humpback dolphin. Anthropogenic sound includes the hearing loss and ear tissue damage of the dolphins from noisy coastal development and shipping. The geographic location of Atlantic humpbacks depend on the water temperature and prey distribution. Climate change causes the fluctuation of water temperatures, which forces the dolphins to adapt to environmental changes.[9]

Conservation

The current conservation status of the Atlantic Humpback is critically endangered, according to the IUCN.[1] This is because of the dolphin's restricted range, specific habitat, low population size, and continued human threats.[10] Coastal development with the associated disturbance in Africa is inevitable and will continue to harm the shy species, whether it is directly or indirectly. The dolphins have already been challenged by climate change and have evolved adequate adaptations because of the impact of human activities. It does not live in the cold, deep waters in the ocean because of the rise in world temperature. The only place left for these dolphins to live is the shallow, warm waters in the ocean. If the world temperature continues to rise, there will be no habitat for the dolphins to successfully thrive and reproduce.[10]

Properly enforced state laws about bycatch and marine protected areas are one solution in conserving the dolphins.[9] Enforcing such a law that states fishing nets cannot be cast a certain distance from the shore will ensure dolphin survival because there would be less incidental dolphin captures. Educating the community to be aware of the threats they are making to the dolphins via public awareness campaigns or training will improve their knowledge on marine life conservation.

Scientific researchers are finding more information about Atlantic Humpbacks and are currently investigating how human activities can decrease the impact on the species.[10]

See also

References

- Collins, T.; Braulik, G.T. & Perrin, W. (2018) [errata version of 2017 assessment]. "Sousa teuszii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T20425A123792572.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- "Humpback dolphin". iwc.int. Retrieved 2022-10-19.

- Jefferson, Thomas A.; Rosenbaum, Howard C. (October 2014). "Taxonomic revision of the humpback dolphins ( Sousa spp.), and description of a new species from Australia". Marine Mammal Science. 30 (4): 1494–1541. doi:10.1111/mms.12152.

- Berta, Annalisa, ed. (2015). Whales, Dolphins & Porpoises: A Natural History and Species Guide. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226183190.

- "Atlantic humpback dolphins | Sousa teuszii". Sousa teuszii | CCAHD - Consortium for the Conservation of the Atlantic Humpback Dolphin. 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2022-10-19.

- Weir, C R (2009-12-01). "Distribution, behaviour and photo-identification of Atlantic humpback dolphins Sousa teuszii off Flamingos, Angola". African Journal of Marine Science. 31 (3): 319–331. doi:10.2989/AJMS.2009.31.3.5.993. ISSN 1814-232X. S2CID 85354627.

- "Atlantic humpback dolphin". Whale & Dolphin Conservation USA. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- Weir, Caroline R.; Waerebeek, Koen Van; Jefferson, Thomas A.; Collins, Tim (2011-04-01). "West Africa's Atlantic Humpback Dolphin (Sousa teuszii): Endemic, Enigmatic and Soon Endangered?". African Zoology. 46 (1): 1–17. doi:10.3377/004.046.0101. ISSN 1562-7020. S2CID 86168629.

- "Conservation status of the Atlantic humpback dolphin, a compromised future? | Sousa teuszii". Sousa teuszii | CCAHD - Consortium for the Conservation of the Atlantic Humpback Dolphin. 2020-12-02. Retrieved 2022-10-19.