Sondergericht

A Sondergericht (plural: Sondergerichte) was a German "special court". After taking power in 1933, the Nazis quickly moved to remove internal opposition to the Nazi regime in Germany. The legal system became one of many tools for this aim and the Nazis gradually supplanted the normal justice system with political courts with wide-ranging powers. The function of the special courts was to intimidate the German public, but as they expanded their scope and took over roles previously done by ordinary courts such as Amtsgerichte this function became diluted.

Function in Germany

Special courts had existed in Germany as far back as the nineteenth century. They had generally been set up temporarily in response to some major but localised civil disturbance and then quickly dissolved once they had served their purpose. A more permanent national network of Special Courts came into being during 1933, soon after the passage of the Reichstag Fire Decree, which all but eliminated civil liberties. The scope of its power was successively augmented by the

- "Decree to Protect the Government of the National Socialist Revolution from Treacherous Attacks" (21 March 1933),

- the "Law of 20 December 1934 against insidious Attacks upon the State and Party and for the Protection of the Party Uniform",

- the "Law for the Guarantee of Peace Based on Law" of 13 October 1933

- and a number of extensions when World War II commenced.[1]

The number of Special Courts increased from 26 in 1933 to 74 in 1942.

A special court had three judges, and the defense counsel was appointed by the court. Even as heavy-handed as justice was in Nazi Germany, defendants were afforded at least nominal protections under the regular courts' rules and procedures. These protections were swept away in the special courts, since they existed outside the ordinary judicial system. There was no possibility of appeal, and verdicts could be executed at once. The court decided the extent of evidence to consider, and "the defense attorneys couldn't question the proof of the charges".[1]

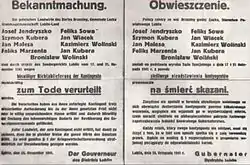

Occupied Poland

The special courts played a major role in carrying out summary executions via judicial murder in Nazi occupied Poland. In December 1941, a special law was introduced by the Germans which allowed for the courts to sentence Poles and Jews to death for virtually anything.[2] Terminology in the courts was full of statements such as "Polish subhumans" and "Polish rabble",[3] with some judges even declaring that Poles were to have lengthier sentences than Germans since they were racially inferior.[3]

Other occupied territories

In countries under German military occupation, such as Norway, Sondergerichte were also set up. Special penal codes were set up, e.g. the Polensonderstrafrechtsverordnung (Poland Special Criminal Law Regulation).

Germany (1934–1945)

The People's Court (Volksgerichtshof) was created in April 1934 for dealing with cases of treason or attacks on national or regional government members.

The reason the court was created was dissatisfaction with the fact that most of the Communists that had been charged with burning down the Reichstag were acquitted. The function of this court was just as that of the special courts, to suppress opposition to the regime.[4]

The workload was divided between the People's Courts and the Special Courts in such a way that the former took the most important cases, while the latter dealt with a wider array of "crimes" of opposition to the Nazis.

Bavaria (1918–1924)

The People's Courts of Bavaria (Volksgerichte) were special courts established by Kurt Eisner during the German Revolution in November 1918 and part of the Ordnungszelle that lasted until May 1924 after handing out more than 31,000 sentences. It was composed of two judges and three lay judges.[5][6] One of its most notable trials was that of the Beer Hall Putsch conspirators, including Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff, Wilhelm Frick, Friedrich Weber, and Ernst Röhm.[7][8]

Effect

Between 1933 and 1945, 12,000 Germans were executed on the orders of the Sondergerichte set up by the Nazi regime.[9]

Especially during the first years of their existence they "had a strong deterrent effect" against opposition to the Nazis; the German public was intimidated through "arbitrary psychological terror".[10]

Prominent defendants

See also

References

- Andrew Szanajda (2007). The restoration of justice in postwar Hesse, 1945–1949, pp. 24–25. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739118702

- Chrzanowski, Bogdan in Chrzanowski et al. Polska Podziemna na Pomorzu, Oskar, Gdansk, 2005, pg. 54

- Nikolaus Wachsmann, Hitler's Prisons: Legal Terror in Nazi Germany, p.202-203

- Andrew Szanajda (2007). The restoration of justice in postwar Hesse, 1945–1949, p. 24. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739118702 "The underlying purpose of that court was to suppress political opposition to the regime and to familiarize German society with the concept of National Socialist justice. Rather than prosecuting defendants for their actions, the court convicted them on the basis of their attitudes toward National Socialism. Any defendant who did not demonstrate support for the regime was considered a traitor."

- Bauer 2009.

- Landauer 1944, p. 221.

- Volksgericht 1924.

- Fulda 2009, p. 68-69.

- Peter Hoffmann "The History of the German Resistance, 1933–1945"p.xiii

- Andrew Szanajda "The restoration of justice in postwar Hesse, 1945–1949" p.25 "In practice, it signified intimidating the public through arbitrary psychological terror, operating like the courts of the Inquisition." "The Sondergerichte had a strong deterrent effect during the first years of their operation, since their rapid and severe sentencing was feared."

- Bauer, Franz J. (23 December 2009). "Volksgerichte, 1918–1924". Historisches Lexikon Bayerns (in German).

- Der Hitler-Prozeß vor dem Volksgericht in München [The Hitler Trial Before the People's Court in Munich] (in German). 1924.

- Fulda, Bernhard (2009). Press and politics in the Weimar Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954778-4.

- Landauer, Carl (September 1944). "The Bavarian Problem in the Weimar Republic: Part II". Journal of Modern History. 16 (3): 205–223. doi:10.1086/236826. JSTOR 1871460. S2CID 145412298.