Solomon (magister militum)

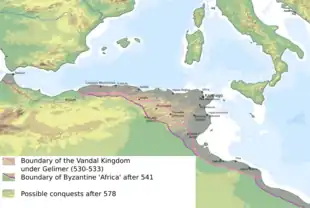

Solomon (Greek: Σολομών) was an East Roman (Byzantine) general from northern Mesopotamia, who distinguished himself as a commander in the Vandalic War and the reconquest of North Africa in 533–534. He spent most of the next decade in Africa as its governor general, combining the military post of magister militum with the civil position of praetorian prefect. Solomon successfully confronted the large-scale rebellion of the native Berbers (Mauri), but was forced to flee following an army mutiny in spring of 536. His second tenure in Africa began in 539 and it was marked by victories over the Berbers, which led to the consolidation of the Byzantine position. A few years of prosperity followed, but were cut short by the rekindled Berber revolt and Solomon's defeat and death at the Battle of Cillium in 544.

Solomon | |

|---|---|

| Born | 480s/490s Idriphthon, near Dara (modern-day Oğuz, Mardin, Turkey) |

| Died | 544 Cillium (modern-day Kasserine, Tunisia) |

| Allegiance | Byzantine Empire |

| Rank | magister militum |

| Battles/wars | Vandalic War, Moorish Wars |

Biography

Solomon was born, probably circa 480/490, in the fortress of Idriphthon in the district of Solachon, near Dara in the province of Mesopotamia. He was a eunuch as a result of an accident during his infancy, not from deliberate castration.[1][2] Solomon had a brother, Bacchus, who became a priest. Bacchus fathered three sons, Cyrus, Sergius and Solomon, who later became military officers in Africa under their uncle; Sergius also succeeded Solomon as governor of Africa after the latter's death.[3] Little is known of Solomon's early career, except that he served under the dux Mesopotamiae Felicissimus, perhaps as early as the latter's installment to the post in 505/6. Certainly by 527, when he came to the service of Belisarius, Solomon was considered an experienced officer.[1] It is perhaps at this time that he was named Belisarius's domesticus, or chief-of-staff, the post with which he is mentioned by the historian Procopius in 533, before the onset of the campaign against the Vandal Kingdom of North Africa.[4][5]

First tenure in Africa

Before the expedition sailed from Constantinople, Solomon was named as one of the nine commanders of the foederati regiments. He is not mentioned in Procopius's narrative during the subsequent campaign, but he probably participated in the decisive Battle of Ad Decimum on 13 September 533, which opened the road for the Vandal capital of Carthage. Following the capture of Carthage, Belisarius sent Solomon back to Constantinople to inform Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565) of the campaign's progress. Solomon remained in the capital until the spring of 534, when Justinian sent him back to Africa to recall Belisarius and replace him as supreme military commander of the new praetorian prefecture of Africa (magister militum Africae).[2][6] Belisarius's departure coincided with a general uprising of the Berber tribes of the interior, before the Byzantines had time to strengthen their hold on the province. As a result, Belisarius left most of his privately raised bucellarii behind, and Emperor Justinian sent additional reinforcements. Soon (sometime in autumn of 534) Emperor Justinian also invested Solomon with the civil office of praetorian prefect as well, replacing the aged Archelaus.[7][8]

In the meantime, the Berbers had invaded Byzacena and defeated the local Byzantine garrison, killing its commanders, Aigan and Rufinus. After diplomatic entreaties over the winter failed, and with his forces bolstered to some 18,000 men (as estimated by Charles Diehl) following the arrival of reinforcements, in spring 535 Solomon led his troops into Byzacena. The Berbers, under their chiefs Cutzinas, Esdilasas, Iourphouthes and Mesidinissas had encamped at a location called Mammes. Solomon attacked them there and defeated them.[9][10] The Byzantine army returned to Carthage, but there news came that the Berbers, reinforced, had again attacked and overrun Byzacena. Solomon immediately marched out and met them at Mount Bourgaon, where the Berbers had erected a fortified camp and awaited his attack. Solomon divided his forces and sent 1,000 men to attack the Berbers from behind, scoring a decisive victory: the Berbers broke and scattered, suffering great casualties. Those who survived fled to Numidia, where they joined the forces of Iaudas, the leader of the tribes of Mount Aurasium.[11][10] With Byzacena secured, and urged by his own Berber allies Massonas and Ortaias, Solomon now turned to Numidia. He cautiously advanced to Aurasium and challenged Iaudas to battle, but after three days, distrusting the loyalty of his allies, Solomon returned his army to the plains. He left part of the army to keep watch on the Berbers and established a series of fortified posts along the roads linking Byzacena with Numidia. Solomon then spent the winter preparing a new expedition against Aurasium and also against the Berbers of Sardinia, but his designs were interrupted by a major army mutiny in spring 536.[12][10]

The revolt was caused by dissatisfaction of some of the soldiers, who had taken Vandal wives, with Solomon: the soldiers demanded the property once owned by their wives as their own, but Solomon refused, since this land had been confiscated by imperial decree. A first plot to assassinate Solomon in Easter failed and the conspirators fled into the countryside, but soon open rebellion broke out among the army in Carthage as well. The soldiers acclaimed one of Solomon's subalterns, Theodore, as its leader, and began looting the city. Solomon managed to find refuge in a church, and under the cover of night, with the aid of Theodore, he departed the city by boat for Missua, accompanied among others by the historian Procopius. From there, Solomon and Procopius sailed to Sicily, which had just been conquered by Belisarius, while Solomon's lieutenant Martin was dispatched to try and reach the troops at Numidia, and Theodore instructed to hold Carthage.[2][12][10] Upon hearing about the mutiny, Belisarius, with Solomon and 100 picked men, set sail for Africa. Carthage was being besieged by 9,000 rebels, including many Vandals, under a certain Stotzas. Theodore was contemplating capitulation when Belisarius appeared. The news of the famous general's arrival were sufficient for the rebels to abandon the siege and withdraw westwards. Belisarius immediately gave pursuit and caught up and defeated the rebel forces at Membresa. The bulk of the rebels, however, was able to flee, and continued to march towards Numidia, where the local troops decided to join them. Belisarius himself was forced to return to Italy due to trouble there, and Emperor Justinian appointed his cousin Germanus as magister militum to deal with the crisis. Solomon returned to Constantinople.[2][13][14]

Second tenure in Africa

Germanus was successful in winning the confidence of many soldiers, re-establishing discipline and defeating the mutineers at the Battle of Scalas Veteres in 537.[16] With imperial control over the army restored, Solomon was sent back to Africa to replace Germanus in 539, again combining in his person the posts of magister militum and praetorian prefect (in the meantime, he had also been raised to the rank of patricius and named an honorary consul).[2][17] Solomon further reinforced his control of the army by weeding out unreliable soldiers, sending them to Belisarius in Italy and to the East; by expelling all remaining Vandals from the province; and by initiating a massive programme of fortification across the region.[18][19]

In 539 AD Solomon [...] devoted the energies of the state to an enormous building programme that fortified the Byzantine province of Africa. The open cities and villa-dotted countryside of the past was transformed into a medieval landscape of small walled towns surrounded by fortified manor houses [...] at the same time sewer systems were overhauled, aqueducts reconnected, harbours cleared and grandiose churches erected to dominate the new urban centres [...] The three great rectangular military fortresses, which were constructed on the south-western frontier zone of Tebessa, Thelepte and Ammaedara, would have required over a million laboring days in their construction.[20]

In 540, Solomon led his army again against the Berbers of Mount Aurasium. Initially, the Berbers attacked and besieged the Byzantine advance guard, under Guntharis, at their camp in Bagai, but Solomon with the main army came to the rescue. The Berbers had to abandon the attack and retreated to Babosis on the foothills of Aurasium, where they pitched camp. Solomon attacked them there and defeated them. The surviving Berbers fled south to Aurasium or west into Mauretania, but their leader Iaudas sought refuge in the fortress of Zerboule. Solomon and his troops plundered the fertile plains around Thamugad, gathering the rich harvest for themselves, before moving onto Zerboule. Once there, they found Iaudas gone, having fled to the remote fortress of Toumar. The Byzantines moved up to besiege Toumar, but the siege proved problematic because of the barren terrain, and in particular the lack of water. While Solomon was considering how best to attack the inaccessible fortress, a minor skirmish between the two forces gradually escalated into a full-scale and confused battle, as more and more soldiers from both sides joined in. The Byzantines emerged victorious, while the Berbers fled from the field. Shortly after, the Byzantines also captured the fort at the so-called "Rock of Geminianus", where Iaudas had sent his wives and treasure.[21][19] This victory left Solomon in control of Aurasium, where he built a number of fortresses. With Aurasium secured, effective Byzantine control was established in the provinces of Numidia and Mauretania Sitifensis. Aided by the captured treasure of Iaudas, Solomon extended his fortification programme in these two provinces: some two-dozen inscriptions testifying to his building activity survive from the area. The Berber rebellion seemed beaten for good, and contemporary chroniclers are unanimous in declaring the next few years as a golden era of peace and prosperity.[22][19]

In the words of Procopius, "all the Libyans who were subjects of the Romans, coming to enjoy secure peace and finding the rule of Solomon wise and very moderate, and having no longer any thought of hostility in their minds, seemed the most fortunate of all men".[23] His restoration programme reached at least as far as the Jedars south of Tiaret; medieval Arabic sources record that the Fatimid caliph al-Mansur bi-Nasr Allah (r. 946–953) encountered there an inscription commemorating Solomon's putting down a revolt of the local Berbers, possibly referring to the Mauro-Roman Kingdom of Mastigas.[24] This expedition once more extended Roman rule to the interior of what once was the province of Mauretania Caesariensis, but this was evidently short-lived: within a few years after Solomon's death, Roman rule in the central Maghreb was reduced to the coasts.[25]

This tranquility lasted until 542/3, when the great plague arrived in Africa and caused many casualties, especially among members of the army. In addition, in early 543 the Berbers in Byzacena became restive. Solomon executed the brother of the chieftain Antalas, whom he held responsible for the disturbances, and ceased the subsidies granted to Antalas, alienating the powerful and hitherto loyal chieftain. At the same time, Solomon's nephew Sergius, newly named governor of Tripolitania as a token of Emperor Justinian's gratitude (along with his brother Cyrus in the Pentapolis), caused the outbreak of hostilities with the tribal confederation of the Leuathae when his men killed 80 of their leaders at a banquet. Although in a subsequent battle near Leptis Magna he was victorious, in early 544 Sergius was forced to travel to Carthage and seek his uncle's aid.[26][19] The rebellion spread quickly from Tripolitania to Byzacena, where Antalas joined it. Joined by his three nephews, Solomon marched against the Berbers as they assembled, meeting them near Theveste. Last-minute diplomatic overtures to the Leuathae failed, and the two armies clashed at Cillium, on the border of Numidia and Byzacena. The Byzantine army was riven by disunity, with many soldiers refusing to fight or doing so only reluctantly. The contemporary poet Flavius Cresconius Corippus even accused Guntharis of treason, alleging that he withdrew from the line with his troops, causing a general and disorderly Byzantine retreat. Solomon and his bodyguard stood their ground and resisted but at last they were forced to retreat. Solomon's horse stumbled and fell in a ravine, wounding its rider. With the aid of his guards, Solomon remounted, but they were quickly overcome and slain.[2][27][19]

Solomon was succeeded by his nephew Sergius, who proved completely inadequate in dealing with the situation. The Berbers launched a general revolt and inflicted a severe defeat on the Byzantines in Thacia in 545. Sergius was recalled, while the army mutinied again, this time under Guntharis, who captured Carthage and installed himself there as an independent ruler. His usurpation did not last long as he was assassinated by Artabanes, but it was not until the arrival of John Troglita in late 546 and his subsequent campaigns that the province was to be pacified and brought again securely under Byzantine imperial control.[28]

References

- Martindale 1992, p. 1168.

- ODB, "Solomon", pp. 1925–1926.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 162, 374, 1124–1128, 1177.

- & Martindale 1992, pp. 1168–1169.

- Bury 1958, p. 129.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 1169–1170.

- & Martindale 1992, p. 1170.

- & Bury 1958, pp. 140–141.

- & Martindale 1992, pp. 1170–1171.

- & Bury 1958, p. 143.

- & Martindale 1992, p. 1171.

- & Martindale 1992, p. 1172.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 1172–1173.

- & Bury 1958, pp. 143–144.

- Graham 2002, pp. 44ff..

- Bury 1958, pp. 144–145.

- Martindale 1992, p. 1173.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 1173–1174.

- Bury 1958, p. 145.

- Rogerson 2001, p. 111.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 1174–1175.

- Martindale 1992, p. 1175.

- Procopius, On the Vandalic War, II.40.

- Halm 1987, pp. 251–255.

- Halm 1987, p. 255.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 1125, 1175.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 1175–1176.

- Bury 1958, pp. 146–147.

Sources

- Bury, John Bagnell (1958). History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian, Volume 2. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20399-9.

- Graham, Alexander (2002) [1902]. Roman Africa. North Stratford, New Hampshire: Ayer Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 0-8369-8807-8.

- Halm, Heinz (1987). "Eine Inschrift des "Magister Militum" Solomon in arabischer Überlieferung: Zur Restitution der "Mauretania Caesariensis" unter Justinian". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte (in German). 36 (2): 250–256. JSTOR 4436011.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Martindale, John R., ed. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume III, AD 527–641. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20160-8.

- Rogerson, Barnaby (2001). History of North Africa. New York: Interlink Books. ISBN 1-56656-351-8.