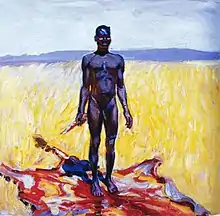

Skinning

Skinning is the act of skin removal. The process is done by humans to animals, mainly as a means to prepare the meat beneath for cooking and consumption, or to harvest the skin for making fur clothing or tanning it to make leather. The skin may also be used as a trophy or taxidermy, sold on the fur market, or, in the case of a declared pest, used as proof of kill to obtain a bounty from a government health, agricultural, or game agency.[1]

Two common methods of skinning are open skinning and case skinning. Typically, large animals are open skinned and smaller animals are case skinned.[2]

Skinning, when it is performed on live humans as a form of torture, murder or capital punishment, is referred to as flaying.

Skinning methods

Case skinning is a method where the skin is peeled from the animal like a sock. This method is usually used if the animal is going to be stretched out or put in dry storage.[3] Many smaller animals are case skinned, leaving the skin mostly undamaged in the shape of a tube.[4]

Although the methods of case skinning individual animals vary slightly, the general steps remain the same. To case skin an animal, it is hung upside down by its feet. A cut is made in one foot, and continued up the leg, around the anus and down the other leg. From there the skin is pulled down the animal as though removing a sweater.[5]

Open skinning is a method where the skin is removed from the animal like a jacket. This method is generally used if the skin is going to be tanned immediately or frozen for storage. A skin removed by the open method can be used for wall hangings or rugs.[6] Larger animals are often skinned using the open method.[7]

To open skin an animal, the body is placed on a flat surface. A cut is made from the anus to the lower lip, and up the legs of the animal. The skin is then opened and removed from the animal.[8]

The final step is to scrape the excess fat and flesh from the inside of the skin with a blunt stone or bone tool.[9]

Dorsal skinning is very similar to open skinning, however instead of making a cut up the stomach of the animal, the cut is made along the spine. This method of skinning is very popular among taxidermists, as the backbone is easier to access and cleaner than the stomach and between the legs.[10] A dorsal incision is made by laying the animal on its abdomen and making a single cut from the base of the tail to the shoulder region. The animal's skin is easier to remove if the animal has been freshly killed.[11]

Cape skinning is the process of removing the shoulder, neck and head skin for the purpose of displaying the animal as a trophy.[12]

Animal skins and Native Americans

Native Americans used skins for many purposes other than decoration, clothing and blankets. Animal skin was a staple in the Native Americans' daily lives. It was used to make tents, to build boats, to make bags, to create musical instruments such as drums, and to make quivers.[13]

Since Native Americans were practiced in the means of acquiring and manipulating animal skin, fur trading developed from contact between them and Europeans in the 16th century. Animal skin was a valuable currency which the Native Americans had in excess and would trade for things such as iron-based tools and tobacco which were common in the more developed European areas.[14] Beaver hats became very popular towards the end of the 16th century, and skinning beavers was necessary to acquire their wool. In this time, the beaver skin drastically rose in demand and in value. However, the high number of beavers being harvested for their pelts led to a depletion of beavers, and the industry had to slow down.[15]

Notes

- "Victorian fox and wild dog bounty / Bounty terms and conditions". agriculture.vic.gov.au.

- Churchill 1983, p.2.

- Burch 2002, p.63

- Burch 2002, p.66

- Churchill 1983, p.44

- Burch 2002, p.63

- Churchill 1983, p.44

- Churchill 1983, p.44

- Wiens, Ray. "Taxidermy and Field Care Tips and Tricks". Hunting Tips and Tricks. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Triplett 2006, p.52

- Triplett 2006, p.53

- Wiens, Ray. "Taxidermy and Field Care Tips and Tricks". Hunting Tips and Tricks. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Pritzer, Barry. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. Print.

- Carlos, Ann M., Frank D. Lewis (February 1, 2011). "The Economic History of the Fur Trade: 1670 to 1870". EH.net encyclopedia. Archived from the original on March 8, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Carlos, Ann M., Frank D. Lewis (February 1, 2011). "The Economic History of the Fur Trade: 1670 to 1870". EH.net encyclopedia. Archived from the original on March 8, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

- Burch, Monte. The Ultimate Guide to Skinning and Tanning: A Complete Guide to Working With Pelts, Furs and Leathers. Guilford: The Lyons Press, 2002. Print.

- James E. Churchill. The Complete Book of Tanning Skins and Furs. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 1983. Print.

- Pritzer, Barry. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. Print.

- Triplett, Todd. Big-Game Taxidermy: A Complete Guide to Deer, Antelope and Elk. United States of America: The Lyons Press, 2006. Print.