Skeletocutis

Skeletocutis is a genus of about 40 species of poroid fungi in the family Polyporaceae. The genus has a cosmopolitan distribution, although most species are found in the Northern Hemisphere. It causes a white rot in a diverse array of woody substrates, and the fruit bodies grow as a crust on the surface of the decaying wood. Sometimes the edges of the crust are turned outward to form rudimentary bracket-like caps.

| Skeletocutis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletocutis nivea on dead branch of common hazel; Slovenia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Skeletocutis |

| Type species | |

| Skeletocutis amorpha (Fr.) Kotl. & Pouzar (1958) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Skeletocutis is primarily distinguished from similar genera of wood-rotting fungi by microscopic features, especially by the sausage-shaped to ellipsoid spores, and spiny crystals covering certain hyphae in the pore tissue. The genus was circumscribed by Czech mycologists František Kotlaba and Zdenek Pouzar in 1958, with Skeletocutis amorpha as the type species.

Description

Macroscopic characteristics

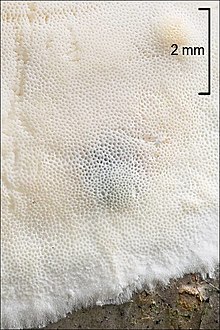

The fruit bodies of Skeletocutis are annual to perennial. They are resupinate (crust-like) to pileate (that is, with a cap). When caps are present, their colour is typically white, cream-pink, or lilac, although the fruit body tends to discolour somewhat when dry. The pores are small and round to irregular in shape. Many Skeletocutis species have a zone of dense cartilaginous tissue above the tube layer;[2] this zone has a gelatinous texture when fresh.[3]

Microscopic characteristics

The hyphal system is dimitic or trimitic. The generative hyphae have clamps, and are often encrusted with spiny crystals, particularly in the dissepiments (tissue that is found between the pores). The skeletal hyphae are hyaline (translucent).[2] Although typically only the generative hyphae of Skeletocutis fungi have incrustations, three species are reported to have apical incrustations on the skeletal hyphae: S. alutacea and S. percandida, and S. novae-zelandiae. Ţura and colleagues suggest that the "taxonomy of these species is poorly worked-out."[4]

Cystidia are absent in the hymenium, but cystidioles are present in most species.[2] The spores are smooth,[3] hyaline, and have an allantoid (sausage-like) to cylindric to ellipsoid shape. They do not have reaction with Melzer's reagent.[2] The basidia (spore-bearing cells) are club shaped to barrel shaped and four spored,[3] measuring 8–15 by 4–5 μm.[5] Although the majority of Skeletocutis species have thin-walled spores, six species have spores with thick walls: S. alutacea, S. bambusicola, S. borealis, S. krawtzewii, S. percandida, and S. perennis.[6]

Ecology, habitat, and distribution

Skeletocutis causes a white rot in a diverse array of woody substrates. Although the majority of species are found growing on the dead wood of various conifer and hardwood genera, some are known to grow on the dead fruit bodies of other polypores. For example, S. brevispora feeds on Phellinidium ferrugineofuscum, while S. chrysella eats Phellinus chrysoloma.[2] The tropical Chinese species S. bambusicola grows on dead bamboo.[6] S. percandida has been reported growing on exotic bamboos cultivated in France.[7] In the Daxing'anling forest areas of northeastern China, S. ochroalba has been found growing on charred wood after forest fires, and may be a pioneer species for this substrate.[8]

In the southern part of the Russian Far East, S. odora is common in aspen forests. It is often found fruiting in association with other fungi, including Fomitopsis rosea, Crustoderma dryinum, Leptoporus mollis, and Phlebia centrifuga.[5] S. odora favours large logs more than 30–50 cm (12–20 in) in diameter. This species is part of the community of fungal successors of decaying wood. A Finnish study found that it fruited most frequently in the third stage (medium decay) of wood decomposition of Norway spruce (Picea abies). In this stage, which occurs about 20–40 years after the death of the plant, the decay penetrates more than 3 cm (1.2 in) into the wood, while the core is still hard.[9] S. carneogrisea and S. kuehneri are successor species that grow on the dead fruit bodies of the polypores Trichaptum abietinum and T. fuscoviolaceum.[10][11]

Skeletocutis has a cosmopolitan distribution, although most species are found in the Northern Hemisphere.[12] Leif Ryvarden considered 22 species to occur in Europe in his 2014 work Poroid Fungi of Europe.[2] Viacheslav Spirin reported 13 species in Russia in 2005.[5] Twenty-two species have been recorded in China.[6][13]

Conservation

In Europe, Skeletocutis odora appears on the national Red Lists of threatened fungi in 5 countries and is one of 33 species of fungi proposed for international conservation under the Bern Convention. Its natural habitat is threatened by deforestation and loss of thick fallen logs typical of old-growth forests.[14] In Estonia, S. odora and S. stellae are used as indicator species to help assess whether forest stands should be protected. They are associated with old-growth forest areas that have been minimally impacted by humans.[15] In contrast, S. lilacina is found exclusively in selectively logged forests, while S. stellae inhabits both types of forest.[16] The Argentinian species S. nothofagi, known only from Tierra del Fuego, has been proposed for inclusion in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species due to its highly restricted distribution and rare occurrence.[17]

Taxonomy

The genus was circumscribed by Czech mycologists František Kotlába and Zdeněk Pouzar in 1958 with Skeletocutis amorpha (originally described as Polyporus amorphus by Elias Magnus Fries in 1815[18]) as the type and only species.[19] The generic name Skeletocutis is derived from the Ancient Greek word σκελετός (skeleto, "dried up") and the Latin word cutis ("skin").[20]

Other genera that feature encrustations in the hyphae of the dissepiment edges include Tyromyces and Piloporia.[6] Molecular analyses has shown the close phylogenetic relationship between Skeletocutis and Tyromyces.[21][22] These two genera group together in the tyromyces clade, on a branch lying outside of the core polyporoid clade,[23] or in the "residual polypore clade" of Tomšovský and colleagues.[24]

Two species formerly placed in Skeletocutis, S. lenis (P.Karst.) Niemelä and S. vulgaris (Fr.) Niemelä & Y.C.Dai, were transferred to the new genus Sidera based on molecular analysis. Although Sidera is placed in a different order (Hymenochaetales), it shares many characteristic features with Skeletocutis, including whitish resupinate basidiocarps (in many species) with small pores, and narrow skeletal hyphae. In contrast with Skeletocutis, however, the hyphae in Sidera comprising the dissepiment edge are smooth or covered with only a few faceted crystal clusters.[25]

In 1963, Polish mycologist Stanislaw Domanski circumscribed the genus Incrustoporia (typified by Poria stellae) to contain several polypores featuring encrusted hyphae at the dissepiments.[26] In 1969, John Ericksson and Åke Strid added Polyporus semipileatus Peck to the genus.[27] The taxonomic placement of this fungus had long before confused mycologists, who had given it a variety of scientific names.[28] Three years before, Pouzar created the genus Leptotrimitus to contain this fungus, as he was not satisfied with other possible generic placements. The main distinguishing feature of Leptotrimitus was the presence of trimitic hyphae.[29] In 1971, Marinus Anton Donk reunited Incrustoporia and Leptotrimitus, as he did not believe that the trimitic character alone was a sufficient criterion for delineating a new genus when so many other characters were identical.[30] Jean Keller studied the ultrastructure of the encrusted hyphae of Incrustoporia species using electron microscopy. He determined that, with the exception of I. carneola, the crystallizations were similar in all instances. The crystals of I. carneola were in the shape of small regular parallelepipeds—clearly distinct from the spiny crystal structures characteristic of the rest of Incrustoporia. Because Skeletocutis was published earlier, it had priority over the generic name Incrustoporia, and so Keller transferred the remaining six species to Skeletocutis in 1989: S. alutacea, S. nivea, S. percandida, S. stellae, S. subincarnata, and S. tschulymica.[28] Incrustoporia carneola was transferred to Junghuhnia as J. carneola.[31]

The inclusion of several monomitic species by Alix David in 1982 (S. azorica, S. jelicii, S. portcrosensis and S. subsphaerospora)[32] was controversial,[33] as mycologists Leif Ryvarden and Robert Lee Gilbertson (1993, 1994)[34][35] and Annarosa Bernicchia (2005)[36] transferred them to or accepted them in Ceriporiopsis. Later molecular work demonstrated that two of these monomitic species, S. azorica and S. subsphaerospora, are phylogenetically much closer to the Skeletocutis-Tyromyces sensu stricto group of species than to Ceriporiopsis,[24] and the current concept of Skeletocutis includes monomitic species.[25] S. jelicii and S. portcrosensis remain in Ceriporiopsis.[37][38]

Species

A 2008 estimate placed around 30 species in the widely distributed genus.[39] As of September 2016, the nomenclatural database Index Fungorum accepts 41 species.[40]

- Skeletocutis africana Ryvarden & P.Roberts (2006)[41] – Cameroon

- Skeletocutis albocremea A.David (1982)[32] – Russia[5]

- Skeletocutis alutacea (J.Lowe) Jean Keller (1979)[28] – United States, Europe

- Skeletocutis amorpha (Fr.) Kotl. & Pouzar (1958) – China;[42] Europe; Africa; Australia

- Skeletocutis azorica (D.A.Reid) Jülich (1982)[43] – Portugal

- Skeletocutis bambusicola L.W.Zhou & W.M.Qin (2012)[6] – China

- Skeletocutis bicolor (Lloyd) Ryvarden (1992)[44] – Singapore

- Skeletocutis biguttulata (Romell) Niemelä (1998)[45] – Russia[5]

- Skeletocutis borealis Niemelä (1998)[45] – Europe

- Skeletocutis brevispora Niemelä (1998)[45] – China; Europe[5]

- Skeletocutis brunneomarginata Ryvarden (2009)[46] – United States

- Skeletocutis carneogrisea A.David (1982)[32] – China;[47] Europe; South America

- Skeletocutis chrysella Niemelä (1998)[45] – Europe

- Skeletocutis diluta (Rajchenb.) A.David & Rajchenb. (1992)[48] – pantropical

- Skeletocutis falsipileata (Corner) T.Hatt. (2002)[49] – Asia

- Skeletocutis fimbriata Juan Li & Y.C.Dai (2008)[50] – China

- Skeletocutis friata Niemelä & Saaren. (2001)[51] – Europe

- Skeletocutis inflata B.K.Cui (2013)[52] – southern China

- Skeletocutis krawtzewii (Pilát) Kotl. & Pouzar (1991)[53] – China; Siberia[54]

- Skeletocutis kuehneri A.David (1982)[32] – Great Britain; Netherlands; Russia

.jpg.webp)

- Skeletocutis lilacina A.David & Jean Keller (1984)[55] – China; Europe; North America[56]

- Skeletocutis luteolus B.K.Cui & Y.C.Dai (2008)[12] – China

- Skeletocutis microcarpa Ryvarden & Iturr. (2003)[57] – Venezuela

- Skeletocutis mopanshanensis (2017)[58] – China

- Skeletocutis nivea (Jungh.) Jean Keller (1979)[28] – Africa, Europe, Australia, New Zealand; China[47] South America[59]

- Skeletocutis niveicolor (Murrill) Ryvarden (1985)[60] – North America

- Skeletocutis nothofagi Rajchenb. (1979)[61] – Argentina

- Skeletocutis novae-zelandiae (G.Cunn.) P.K.Buchanan & Ryvarden (1988)[62] – New Zealand

- Skeletocutis ochroalba Niemelä (1985)[63] – Canada; China; Central and Northern Europe[64]

- Skeletocutis odora (Sacc.) Ginns (1984)[65] – Slovakia; Russia[5]

- Skeletocutis papyracea A.David (1982)[32] – Europe[5]

- Skeletocutis percandida (Malençon & Bertault) Jean Keller (1979)[28] – Africa (Zimbabwe); Asia (China; Israel); Mediterranean Europe[4]

- Skeletocutis perennis Ryvarden (1986) – China[66]

- Skeletocutis polyporicola Ryvarden & Iturr. (2011)[67] – Venezuela

- Skeletocutis pseudo-odora L.F.Fan & Jing Si (2017)[68] – China

- Skeletocutis roseola (Rick ex Theiss.) Rajchenb. (1987)[69] – Brazil

- Skeletocutis stellae (Pilát) Jean Keller (1979)[28] – China;[47] Argentina;[59] Europe

.jpg.webp)

- Skeletocutis stramentica (G.Cunn.) Rajchenb. (1995)[70] – New Zealand

- Skeletocutis subincarnata (Peck) Jean Keller (1979)[28] – Europe; Canada

- Skeletocutis subodora Vlasák & Ryvarden (2012)[71] – United States

- Skeletocutis substellae Y.C.Dai (2011)[72] – China

- Skeletocutis subvulgaris Y.C.Dai (1998)[73] – China

- Skeletocutis tschulymica (Pilát) Jean Keller (1979)[28] – Europe

- Skeletocutis uralensis (Pilát) Kotl. & Pouzar (1990)[74] – Europe

- Skeletocutis yunnanensis[75] – China

The taxon S. australis, described from South America by Mario Rajchenberg in 1987,[76] was later placed by him in synonymy with the species S. stramentica, originally described from New Zealand.[70]

Index Fungorum shows 66 taxa associated with the generic name Skeletocutis. Several species once placed in this genus have since been moved to other genera:

- Skeletocutis basifusca (Corner) T.Hatt. (2001)[77] = Trichaptum basifuscum Corner (1987)[78]

- Skeletocutis hymeniicola (Murrill) Niemelä (1998)[45] = Poria hymeniicola Murrill (1920)[79]

- Skeletocutis jelicii Tortič & A.David (1981) = Ceriporiopsis jelicii (Tortič & A.David) Ryvarden & Gilb. (1993)[37]

- Skeletocutis portcrosensis A.David (1982)[32] = Ceriporiopsis portcrosensis (A.David) Ryvarden & Gilb. (1993)[38]

- Skeletocutis sensitiva (Lloyd) Ryvarden (1992)[44] = Fomitopsis sensitiva (Lloyd) R.Sasaki (1954)[80]

References

- "Synonymy: Skeletocutis Kotl. & Pouzar". Species Fungorum. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Ryvarden, Leif; Melo, Ireneia (2014). Poroid Fungi of Europe. Synopsis Fungorum. Vol. 31. Oslo, Norway: Fungiflora. p. 388. ISBN 978-8290724462.

- Prasher, I.B. (2015). Wood-rotting non-gilled Agaricomycetes of Himalayas. Springer. p. 480. ISBN 978-94-017-9858-7.

- Ţura, Daniel; Spirin, Wjacheslav A.; Wasser, Solomon P.; Nevo, Eviatar; Zmitrovich, Ivan V. (2008). "Polypores new to Israel – 1: Genera Ceriporiopsis, Postia and Skeletocutis". Mycotaxon. 103: 217–227.

- Spirin, Viacheslav (2005). "Notes on some rare polypores, found in Russia 2. Junghuhnia vitellina sp. nova, plus genera Cinereomyces and Skeletocutis". Karstenia. 45 (2): 103–113. doi:10.29203/ka.2005.409.

- Zhou, L.W.; Qin, W.M. (2012). "A new species of Skeletocutis on bamboo (Polyporaceae) in tropical China". Mycotaxon. 119: 345–350. doi:10.5248/119.345.

- Boidin, J.; Candoussau, F.; Gilles, G. (1986). "Bambusicolous fungi from the Southwest of France II. Saprobic heterobasidiomycetes, resupinate Aphyllophorales and Nidulariales". Transactions of the Mycological Society of Japan. 27 (4): 463–471.

- Yu, Chang-Jun; Dai, Yu-Cheng; Wang, Z. (2004). "A preliminary study on wood-inhabiting fungi on charred wood in Daxinganling forest areas". Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao. 15 (10): 1781–1784. PMID 15624808.

- Stokland, Jogeir N.; Siitonen, Juha; Jonsson, Gunnar (2012). Biodiversity in Dead Wood. Cambridge University Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-521-88873-8.

- Niemelä, Tuomo; Renvall, Pertti; Penttilä, Reijo (1995). "Interactions of fungi at late stages of wood decomposition". Annales Botanici Fennici. 32 (3): 141–152. JSTOR 23726315.

- Komonen, Atte; Halme, Panu; Jäntti, Mari; Koskela, Tuuli; Kotiaho, Janne Sakari; Toivanen, Tero (2014). "Created substrates do not fully mimic natural substrates in restoration: the occurrence of polypores on spruce logs". Silva Fennica. 48 (1). doi:10.14214/sf.980.

- Cui, Bao-Kai; Dai, Yu-Cheng (2008). "Skeletocutis luteolus sp. nov. from southern and eastern China". Mycotaxon. 104: 97–101.

- Dai, Yu-Cheng (2012). "Polypore diversity in China with an annotated checklist of Chinese polypores". Mycoscience. 53: 49–80. doi:10.1007/s10267-011-0134-3. S2CID 86319931.

- Dahlberg, A.; Croneborg, H. (2006). The 33 Threatened Fungi in Europe (Nature and Environment). Strasbourg, Germany: Council of Europe. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-92-871-5928-1.

- Parmasto, Erast (2008). "Fungi as indicators of old-growth forests". In Moore, David; Nauta, Marijke M.; Evans, Shelley E. (eds.). Fungal Conservation: Issues and Solutions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-0-521-04818-7.

- Sippola, Anna-Liisa (2004). "Maintaining biodiversity in managed rorests – Results of beetle and polypore studies in boreal forests" (PDF). In Andersson, Folke; Birot, Yves; Päivinen, Risto (eds.). Towards the Sustainable Use of Europe's Forests – Forest Ecosystem and Landscape Research: Scientific Challenges and Opportunities (Report). European Forest Institute. pp. 259–271. ISBN 952-5453-01-4.

- Rachenberg, Mario. "Skeletocutis nothofagi Rajchenb". The Global Fungal Red List Initiative. IUCN. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Fries, Elias Magnus (1815). Observationes mycologicae (in Latin). Gerhard Bonnier. p. 125.

- Kotlába, F.; Pouzar, Z. (1958). "Polypori novi vel minus cogniti Cechoslovakiae III" (PDF). Ceská Mykologie (in Czech). 12 (2): 95–104.

- Donk, M.A. (1960). "The generic names proposed for Polyporaceae". Persoonia. 1 (2): 173–302.

- Yao, Y.-J.; Pegler, D.N.; Chase, M.W. (1999). "Application of ITS (nrDNA) sequences in the phylogenetic study of Tyromyces s.l.". Mycological Research. 103 (2): 219–229. doi:10.1017/S0953756298007138.

- Kim, Seon-Young; Park, So-Yeon; Jung, Hack-Sung (2001). "Phylogenetic classification of Antrodia and related genera based on ribosomal RNA internal transcribed spacer sequences". Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 11 (3): 475–481.

- Floudas, Dimitrios; Hibbett, David S. (2015). "Revisiting the taxonomy of Phanerochaete (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) using a four gene dataset and extensive ITS sampling" (PDF). Fungal Biology. 119 (8): 679–719 (see p. 694). doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2015.04.003. PMID 26228559.

- Tomšovský, Michal; Menkis, Audrius; Vasaitis, Rimvydas (2010). "Phylogenetic relationships in European Ceriporiopsis species inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial ribosomal DNA sequences". Fungal Biology. 114 (4): 350–358. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2010.02.004. PMID 20943145.

- Miettinen, Otto; Larsson, Karl-Henrik (2011). "Sidera, a new genus in Hymenochaetales with poroid and hydroid species". Mycological Progress. 10 (2): 131–141. doi:10.1007/s11557-010-0682-5. S2CID 23786160.

- Domanski, S. (1963). "Dwa nowe rodzaje grzybów z grupy "Poria Pers. ex S.F. Gray"". Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae (in Polish). 32 (4): 731–739. doi:10.5586/asbp.1963.044.

- Eriksson, John; Strid, Åke (1969). "Studies in the Aphyllophorales (Basidiomycetes) of northern Finland". Annales Universitatis Turku A (II). 40: 112–158.

- Keller, J. (1978). "Ultrastructure des hyphes incrustées dans le genre Skeletocutis" (PDF). Persoonia (in French). 10 (3): 347–355.

- Pouzar, Z. (1966). "Studies in the taxonomy of the Polypores I". Ceská Mykologie. 20 (3): 171–177.

- Donk, M.A. (1971). "Notes on European Polypores—IV". Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Academie van Wetenschappen. Series C: Biological and Medical Sciences. 74: 1–24.

- "Record Details: Incrustoporia carneola (Bres.) Ryvarden". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- David, A. (1982). "Étude monographique du genre Skeletocutis (Polyporaceae)". Le Naturaliste Canadien (in French). 109: 235–272.

- Rachenberg, Mario (2011). "Nuclear behavior of the mycelium and the phylogeny of Polypores (Basidiomycota)". Mycologia. 103 (34): 677–702. doi:10.3852/10-310. hdl:11336/84709. PMID 21471294. S2CID 43416000.

- Ryvarden, Leif; Gilbertson, R.L. (1993). European Polypores 1. Synopsis Fungorum. Vol. 6. Oslo: Fungiflora. ISBN 978-82-90724-12-7.

- Ryvarden, Leif; Gilbertson, R.L. (1994). European Polypores 2: Meripilus-Tyromyces. Synopsis Fungorum. Vol. 7. Oslo: Fungiflora. ISBN 978-82-90724-13-4.

- Berniccia, Annarosa (2005). Polyporaceae s.l. Fungi Europaei. Vol. 10. Alassio, Italy: Candusso. ISBN 978-88-901057-5-3.

- "Record Details: Skeletocutis jelicii Tortič & A. David". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- "Record Details: Skeletocutis portcrosensis A. David". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Kirk, P.M.; Cannon, P.F.; Minter, D.W.; Stalpers, J.A. (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi (10th ed.). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. p. 638. ISBN 978-0-85199-826-8.

- Kirk, P.M. "Species Fungorum (version 26th August 2016). In: Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life". Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Roberts, Peter; Ryvarden, Leif (2006). "Poroid fungi from Korup National Park, Cameroon". Kew Bulletin. 61 (1): 55–78. JSTOR 20443246.

- Dai, Yu-Cheng; Cui, Bao-Kai; Huang, Ming-Yun (2007). "Polypores from eastern Inner Mongolia, northeastern China". Nova Hedwigia. 84 (3–4): 513–520. doi:10.1127/0029-5035/2007/0084-0513.

- Jülich, W. (1982). "Notes on some Basidiomycetes (Aphyllophorales and Heterobasidiomycetes)". Persoonia. 11 (4): 421–428.

- Ryvarden, Leif (1992). "Type studies in the Polyporaceae. 23. Species described by C.G. Lloyd in Lenzites, Polystictus, Poria and Trametes". Mycotaxon. 44 (1): 127–136.

- Niemelä, Tuomo (1998). "The Skeletocutis subincarnata complex (Basidiomycetes), a revision". Acta Botanica Fennica. 161: 1–35.

- Ryvarden, L. (2009). "Some new and interesting polypores from United States". Synopsis Fungorum. 26: 24–26.

- Li, Hai-Jiao; He, Shuang-Hui; Cui, Bao-Kai (2011). "Polypores from Bawangling Nature Reserve, Hainan Province". Mycosystema. 29 (6): 828–833.

- David, Alix; Rajchenberg, Mario (1992). "West African polypores: New species and combinations". Mycotaxon. 45: 131–148.

- Hattori, T. (2002). "Type studies of the polypores described by E.J.H. Corner from Asia and West Pacific Areas. IV. Species described in Tyromyces (1)". Mycoscience. 43 (4): 307–315. doi:10.1007/s102670200045. S2CID 195234251.

- Li, Juan; Xiong, Hong-Xia; Dai, Yu-Cheng (2008). "Two new polypores (Basidiomycota) from Central China". Annales Botanici Fennici. 45 (4): 315–319. doi:10.5735/085.045.0413. S2CID 84500529.

- Niemelä, Tuomo; Kinnunen, Juha; Lindgren, Mariko; Manninen, Olli; Miettinen, Otto; Penttilä, Reijo; Turunen, Olli (2001). "Novelties and records of poroid Basidiomycetes in Finland and adjacent Russia". Karstenia. 41 (1): 1–21. doi:10.29203/ka.2001.373.

- Cui, Bao-Kai (2013). "Two new polypores (Ceriporiopsis lavendula and Skeletocutis inflata spp. nov.) from Guangdong Province, China". Nordic Journal of Botany. 31 (3): 326–330. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.2012.01674.x.

- Kotlaba, F.; Pouzar, Z. (1991). "Type studies of polypores described by A. Pilát – IV". Czech Mycology. 45 (3): 91–97.

- Yu, Chang-Jun; Zuo, Li; Dai, Yu-Cheng (2005). "Three polypores from Xizang new to China" (PDF). Fungal Science. 20 (3–4): 61–68.

- David, A.; Keller, J. (1984). "Une nouvelle espèce de Skeletocutis (Polyporaceae) recoltée en Suisse". Mycologia Helvetica (in French). 1 (3): 157–167.

- Dai, Yu-Cheng; Yuan, Hai-Sheng; Yu, Chang-Jun; Cui, Bao-Kai; Wei, Yu-Lian; Li, Juan. "Polypores from the Great Hinggan Mts., NE China" (PDF). College & Research Libraries. 17: 71–81.

- Ryvarden, Leif; Iturriaga, Teresa (2003). "Studies in neotropical polypores 10. New polypores from Venezuela". Mycologia. 95 (6): 1066–1077. doi:10.1080/15572536.2004.11833021. JSTOR 3761913. PMID 21149014. S2CID 42996705.

- Wu, Zi-Qiang; Wang, Zheng-Hui; Luo, Kai-Yue; Shi, Zhong-Wen; Wu, Fang; Zhao, Chang-Lin (2017). "Skeletocutis mopanshanensis sp. nov. (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) evidenced by morphological characters and phylogenetic analysis". Nova Hedwigia. 107 (1–2): 167–177. doi:10.1127/nova_hedwigia/2017/0461. S2CID 91097610.

- Robledo, Geraldo L.; Rachenberg, Mario (2007). "South American polypores: first annotated checklist from Argentinean Yungas". Mycotaxon. 100: 5–9.

- Ryvarden, Leif (1985). "Type studies in the Polyporaceae 17. Species described by W.A. Murrill". Mycotaxon. 23: 169–198 (see p. 187).

- Rajchenberg, Mario (2001). "A new species and new records of polypore fungi from the Patagonian Andes forests of Argentina". Mycotaxon. 77: 93–100.

- Buchanan, Peter K.; Ryvarden, Leif (1988). "Type studies in the Polyporaceae – 18. Species described by G.H. Cunningham". Mycotaxon. 31 (1): 1–38.

- Niemelä, Tuomo (1985). "Mycoflora of Poste-de-la-Baleine, Northern Quebec. Polypores and the Hymenochaetales". Naturaliste Canadien. 112 (4): 445–472. ISSN 0028-0798.

- Zíbarová, Lucie; Kout, Jiří (2014). "First record of Skeletocutis ochroalba (Polyporales) in the Czech Republic" (PDF). Czech Mycology. 66 (1): 61–69. doi:10.33585/cmy.66104.

- Ginns, J. (1984). "New names, new combinations and new synonymy in the Corticiaceae, Hymenochaetaceae and Polyporaceae". Mycotaxon. 21: 325–333.

- Dai, Yu-Cheng (2003). "Rare and threatened polypores in the ecosystem of Changbaishan Nature Reserve of northeastern China". Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao (in Chinese). 14 (6): 1015–1018. PMID 12974018.

- Ryvarden, Leif; Iturriaga, Teresa (2011). "Studies in Neotropical polypores 30, New and interesting species from Gran Sabana in Venezuela". Synopsis Fungorum. 39: 74–81.

- Fan, L.F.; Ji, X.H.; Si, J. (2017). "A new species in the Skeletocutis subincarnata complex (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) from southwestern China". Mycosphere. 8 (6): 1253–1260. doi:10.5943/mycosphere/8/6/8.

- Rajchenberg, Mario (1987). "Type studies of Polyporaceae (Aphyllophorales) described by J. Rick". Nordic Journal of Botany. 7 (5): 553–568. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.1987.tb02023.x.

- Rajchenberg, Mario (1995). "Notes on New Zealand polypores (Basidiomycetes) 2. Cultural and morphological studies of selected species". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 33 (1): 99–109. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1995.10412947.

- Vlasák, Josef; Vlasák, Josef Jr.; Ryvarden, Leif (2012). "Four new polypore species from the western United States". Mycotaxon. 119: 217–231. doi:10.5248/119.217.

- Dai, Yu-Cheng (2012). "Two new polypores from tropical China and renaming two species of Polyporus and Phellinus". Mycoscience. 53: 40–44. doi:10.1007/s10267-011-0135-2. S2CID 85172197.

- Dai, Yu-Cheng (1998). "Changbai wood-rotting fungi 9. Three new species and other species in Rigidoporus, Skeletocutis and Wolfiporia (Basidiomycota, Aphyllophorales)" (PDF). Annales Botanici Fennici. 35 (2): 143–154. JSTOR 23726542.

- Kotlába, František; Pouzar, Zdeněk (1990). "Type studies of polypores described by A. Pilát – III". Ceská Mykologie. 44 (4): 228–237.

- Bian, Lu-Sen; Zhao, Chang-Lin; Wu, Fang (2016). "A new species of Skeletocutis (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) from Yunnan of China". Phytotaxa. 270 (4): 267. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.270.4.3.

- Rajchenberg, Mario (1987). "Xylophilous Aphyllophorales (Basidiomycetes) from the southern Andean forests. Additions and corrections. II" (PDF). Sydowia. 40: 235–249.

- Hattori, T. (2001). "Type studies of the polypores described by E.J.H. Corner from Asia and West Pacific Areas III. Species described in Trichaptum, Albatrellus, Boletopsis, Diacanthodes, Elmerina, Fomitopsis and Gloeoporus". Mycoscience. 42 (5): 423–431. doi:10.1007/bf02464338. S2CID 84661483.

- "Record Details: Skeletocutis basifusca (Corner) T. Hatt". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- "Record Details: Skeletocutis hymeniicola (Murrill) Niemelä". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- "Record Details: Skeletocutis sensitiva (Lloyd) Ryvarden". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 30 September 2016.