Picea sitchensis

Picea sitchensis, the Sitka spruce, is a large, coniferous, evergreen tree growing to almost 100 meters (330 ft) tall,[2] with a trunk diameter at breast height that can exceed 5 m (16 ft). It is by far the largest species of spruce and the fifth-largest conifer in the world (behind giant sequoia, coast redwood, kauri, and western red cedar),[3] and the third-tallest conifer species (after coast redwood and coast Douglas fir). The Sitka spruce is one of the few species documented to exceed 90 m (300 ft) in height.[4] Its name is derived from the community of Sitka in southeast Alaska, where it is prevalent. Its range hugs the western coast of Canada and the US, continuing south into northernmost California.

| Sitka spruce | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sitka spruce in the Hoh Rainforest in Olympic National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnosperms |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Picea |

| Species: | P. sitchensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Picea sitchensis | |

| |

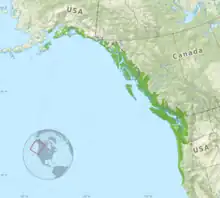

| Range highlighted in dark green | |

| NCBI genome ID | 3332 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | 2 |

| Genome size | 20 Gbp |

| Number of chromosomes | 12 |

| Sequenced organelle | plastid and mitochondrion |

| Organelle size | 124 kbp and 5.52 Mbp |

| Year of completion | 2016 and 2019 |

Description

The bark is thin and scaly, flaking off in small, circular plates 5–20 centimeters (2–8 in) across. The inner bark is reddish-brown.[5] The crown is broad conic in young trees, becoming cylindric in older trees; old trees may not have branches lower than 30–40 meters (98–131 ft). The shoots are very pale buff-brown, almost white, and glabrous (hairless), but with prominent pulvini. The leaves are stiff, sharp, and needle-like, 15–25 millimeters long, flattened in cross-section,[5] dark glaucous blue-green above with two or three thin lines of stomata, and blue-white below with two dense bands of stomata.

The cones are pendulous, slender cylindrical, 6–10 cm (2+1⁄2–4 in) long[6] and 2 cm (3⁄4 in) broad when closed, opening to 3 cm (1+1⁄4 in) broad. They have thin, flexible scales 15–20 mm (5⁄8–3⁄4 in) long; the bracts just above the scales are the longest of any spruce, occasionally just exserted and visible on the closed cones. They are green or reddish, maturing pale brown 5–7 months after pollination. The seeds are black, 3 mm (1⁄8 in) long, with a slender, 7–9 mm (1⁄4–3⁄8 in) long pale brown wing.

Size

More than a century of logging has left only a remnant of the spruce forest. The largest trees were cut long before careful measurements could be made. Trees over 90 m (300 ft) tall may still be seen in Pacific Rim National Park and Carmanah Walbran Provincial Park on Vancouver Island, British Columbia (the Carmanah Giant, at 96 m (315 ft) tall, is the tallest tree in Canada),[7] and in Olympic National Park, Washington and Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, California (United States), the latter of which houses the tallest individual measuring at 100.2 meters or 329 feet tall; two at the last site are just over 96 m tall.[8] The Queets Spruce is the largest in the world with a trunk volume of 346 m3 (12,200 cu ft), a height of 74.6 m (244 ft 9 in), and a 4.4 m (14 ft 5 in) dbh.[9][10] It is located near the Queets River in Olympic National Park, about 26 km (16 mi) from the Pacific Ocean. Another specimen, from Klootchy Creek Park, Oregon, was previously recorded to be the largest with a circumference of 15 metres (49 ft) and height of 66 metres (217 ft).[11]

Age

Sitka spruce is a long-lived tree, with individuals over 700 years old known. Because it grows rapidly under favorable conditions, large size may not indicate exceptional age. The Queets Spruce has been estimated to be only 350 to 450 years old, but adds more than a cubic meter of wood each year.[12]

Root system

Because it grows in extremely wet and poorly-drained soil, the Sitka spruce has a shallow root system with long lateral roots and few branchings. This also makes it susceptible to wind throw.[13]

Taxonomy

DNA analysis[14][15] has shown that only P. breweriana has a more basal position than Sitka spruce to the rest of the spruce. The other 33 species of spruce are more derived, which suggests that Picea originated in North America.[14]

Distribution and habitat

Sitka spruce is native to the west coast of North America, with its northwestern limit on Kenai Peninsula, Alaska, and its southeastern limit near Fort Bragg in northern California.[16] It is closely associated with the temperate rainforests and is found within a few kilometers of the coast in the southern portion of its range. North of Oregon, its range extends inland along river floodplains, but seldom does its range extend more than around 80 km (50 mi) from the Pacific Ocean and its inlets.[5] It is situated at about 2,500 m (8,200 ft) above sea level in Alaska and generally below 450 m (1,480 ft) further south.[5]

Forests with the species average between 200 and 500 cm (79 and 197 in) of rain annually.[5] It is tolerant to salty spray common in coastal dune habitat, such as at Cape Disappointment State Park in Washington, and prefers soils high in magnesium, calcium, and phosphorus.[13]

Sitka spruce has been introduced to Europe as a lumber tree, and was first planted there in the 19th century. Sitka spruce plantations have become a dominant forest type in Great Britain and Ireland, making up 25% of forest cover in the former and 52% in the latter. Sitka spruce woodland is also present in France and Denmark, and the plant was introduced to Iceland and Norway in the early 20th century.[17][18] Observations of Sitka spruce along the Norwegian coast have shown the species to be growing 25–100% faster than the native Norway spruce there, even as far north as Vesterålen, and Sitka spruces planted along the southwest coast of Norway are growing fastest among the Sitka plantations in Europe.[19][20]

A 9-metre-tall, 100-year-old Sitka spruce growing in the middle of the permanently uninhabited sub-antarctic Campbell Island has been recognised by the Guinness World Records as the "most remote tree in the world".[21]

Ecology

Value to wildlife

Sitka spruce provides critical habitat for a large variety of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Its thick, sharp needles are poor browse for ungulates, and only the new spring growth is eaten. However, in Alaska and British Columbia the needles of Picea sitchensis comprise up to 90% of the winter diet of blue grouse.[13]

Lichen-forming fungi Helocarpon lesdainii is found on Picea sitchensis trees in Harris Beach State Park, Oregon, USA.[22]

It provides cover and hiding places for a large variety of mammals, and good nesting and roosting habitat for birds. Sitka deer require old-growth Sitka spruce forests for winter habitat, as the extensive foliage holds a significant percentage of fallen snow in a given area, thus allowing for better understory browsing and easier migration for terrestrial animals. Cavity nesting birds favor Sitka spruce snags, and the tree is used by bald eagles,[5] and peregrine falcons as nesting habitat.

Successional status

Sitka spruce is shade tolerant but not as much as its competitors,[5] preferring full sun if possible. It is a pioneer on landslides, sand dunes, uplifted beaches, and deglaciated terrain. However, it is a climax species in coastal forests, where it can become dominant.[13]

Fire ecology

Due to the prevalence of Sitka spruce in cool, wet climates, its thin bark and shallow root system are not adapted to resist fire damage and it is thus very susceptible. Sitka spruce forests have a fire regime of severe crown or surface fires on long intervals, (150 to 350+ years) which results in total stand replacement. Sitka spruce recolonizes burned sites via wind-dispersed seed from adjacent unburned forests.[13]

Uses

The root bark of Sitka spruce trees is used in Native Alaskan basket-weaving designs[23] and for rain hats. The pitch was used for caulking, chewing, and its medicinal properties.[13] Native Americans heated and plied the roots to make cord.[5] The resin was used as glue and for waterproofing.[5] Natives and pioneers split off shakes for construction use.[5] The wood is light and relatively strong.[5]

Sitka spruce is of major importance in forestry for timber and paper production. Outside its native range, it is particularly valued for its fast growth on poor soils and exposed sites where few other trees can prosper; in ideal conditions, young trees may grow 1.5 m (5 ft) per year. It is naturalized in some parts of Ireland and Great Britain, where it was introduced in 1831 by David Douglas,[24] and New Zealand, though not so extensively as to be considered invasive. Sitka spruce is also planted extensively in Denmark, Norway, and Iceland.[25][26] In Norway, Sitka spruce was introduced in the early 1900s. An estimated 50,000 hectares (120,000 acres) have been planted in Norway, mainly along the coast from Vest-Agder in the south to Troms in the north. It is more tolerant to wind and saline ocean air, and grows faster than the native Norway spruce.[27] But in Norway, the Sitka spruce is now considered an invasive species, and effort to eliminate it is being made.[28][29]

The resonant wood[5] is used widely in piano, harp, violin, and guitar manufacture, as its high strength-to-weight ratio and regular, knot-free rings make it an excellent conductor of sound. For these reasons, the wood is also an important material for sailboat spars, and aircraft wing spars (including flying models). The Wright brothers' Flyer was built using Sitka spruce, as were many aircraft before World War II; during that war, aircraft such as the British Mosquito used it as a substitute for strategically important aluminium.

Newly grown tips of Sitka spruce branches are used to flavor spruce beer and are boiled to make syrup.[30][31]

Indigenous culture

A unique specimen with golden foliage that used to grow on Haida Gwaii, known as Kiidk'yaas or "The Golden Spruce", is sacred to the Haida First Nations people. It was illegally felled in 1997 by Grant Hadwin, although saplings grown from cuttings can now be found near its original site.

In the Lushootseed language, spoken in what is now Washington state, it is known as c̓əlaqayac.[32]

Chemistry

The stilbene glucosides astringin, isorhapontin, and piceid can be found in the bark of the Sitka spruce.[33][34]

Burls

In the Olympic National Forest in Washington, Sitka spruce trees near the ocean sometimes develop burls.

According to a guidebook entitled Olympic Peninsula, "Damage to the tip or the bud of a Sitka spruce causes the growth cells to divide more rapidly than normal to form this swelling or burl. Even though the burls may look menacing, they do not affect the overall tree growth."[35]

See also

References

- Farjon, A. (2013). "Picea sitchensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T42337A2973701. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42337A2973701.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Rushforth, Keith (1986) [1980]. Bäume [Pocket Guide to Trees] (in German) (2nd ed.). Bern: Hallwag AG. ISBN 3-444-70130-6.

- "Agathis australis". Conifers. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- "Tallest Sitka Spruce". Landmark Trees. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Arno, Stephen F.; Hammerly, Ramona P. (2020) [1977]. Northwest Trees: Identifying & Understanding the Region's Native Trees (field guide ed.). Seattle, Washington: Mountaineers Books. pp. 83–91. ISBN 978-1-68051-329-5. OCLC 1141235469.

- "Picea sitchensis". Oregon State University. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Stoltmann, Randy, 1962– (1996). Hiking the ancient forests of British Columbia and Washington. Vancouver, B.C.: Lone Pine. ISBN 1551050455. OCLC 35161377.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Picea sitchensis". Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

This tree also has a sign nearby proclaiming it to be 'the world's largest spruce'. The two tallest on record, 96.7 m and 96.4 m, are in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, California

- Van Pelt, Robert. (2015). Champion trees of washington state. Seattle, Washington, USA: Univ of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295997452. OCLC 921868759.

- "The 100.2 m tall Sitka Spruce | Wondermondo". www.wondermondo.com. 26 June 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- Traver, Robert (1985). America's Wild Woodlands. National Geographic Society. p. 12. ISBN 9780870445422.

- Van Pelt, Robert (2001). Forest Giants of the Pacific Coast. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295981407.

- "Index of Species Information: Picea sitchensis". Fire Effects Information System. U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- Ran, J. H.; Wei, X. X.; Wang, X. Q. (2006). "Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of Picea (Pinaceae): Implications for phylogeographical studies using cytoplasmic haplotypes". Mol Phylogenet Evol. 41 (2): 405–419. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.039. PMID 16839785.

- Sigurgeirsson, A.; Szmidt, A. E. (1993). "Phylogenetic and biogeographic implications of chloroplast DNA variation in Picea". Nordic Journal of Botany. 13 (3): 233–246. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.1993.tb00043.x.

- Griffin, J. R.; Critchfield, W. B. (1976). Distribution of forest trees in California. USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) Forest Service Research Paper. pp. 23–24, 75. PSW-82.

- Bill, Mason; Perks, Michael P. (21 March 2011). "Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) forests in Atlantic Europe: changes in forest management and possible consequences for carbon sequestration". Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research. 26 (S11): 72–81. Bibcode:2011SJFR...26S..72M. doi:10.1080/02827581.2011.564383. S2CID 85059411.

- Houston Durrant, T.; A., Mauri; D., de Rigo; Caudullo, G. (2016). "Picea sitchensis in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats" (PDF). Forest.jrc. European Commission. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Vestlandsk sitkagran vokser best i Europa". 29 September 2014.

- "Ligg unna sitkagrana i klimaskogen min". 10 March 2019.

- "Is this the world's loneliest tree? The 100-year-old tale of survival on an uninhabited New Zealand island". ABC News. 4 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- "Helocarpon lesdainii | Oregon Digital". oregondigital.org. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- Kallenbach, Elizabeth. "Tlingit Spruce Root Baskets". University of Oregon, Museum of Natural and Cultural History. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- Mitchell, A. (1978). Trees of Britain & Northern Europe. Collins Field Guide. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-219213-6.

- Dammert, L. (2001). "Dressing the landscape: afforestation efforts on Iceland]". Unasylva. 52 (207).

- Hermann, R. (1987). "North American Tree Species in Europe" (PDF). Journal of Forestry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2006. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

Efforts to remove this species have been initiated in Norway as the Sitka spruce dominates the native ecology with few native species managing to compete or thrive in its shadow.

- Vadla, Kjell. "Sitkagran – utbredelse, egenskaper og anvendelse" [Sitka spruce – propagation, properties and uses]. Norwegian Forest and Landscape Institute (in Norwegian).

- "Vil utrydde granskog på Vestlandet og i Nord-Norge". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "Her svir de av øyene nord for Herdla". Askøyværingen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "Picea sitchensis: "Sitka Spruce, Tideland Spruce"". Collections. San Francisco Botanical Garden. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- "Alaska State Tree: Sitka Spruce". Alaskan Nature. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- "c̓əlaqayac". Lushootseed. 10 May 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- Aritomi, Masakazu; Donnelly, Dervilla M. X. (1976). "Stilbene glucosides in the bark of Picea sitchensis". Phytochemistry. 15 (12): 2006–2008. Bibcode:1976PChem..15.2006A. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)88881-0.

- Underwood, Claudia D. Toscano & Pearce, Raymond B. (1991). "Astringin and isorhapontin distribution in Sitka spruce trees". Phytochemistry. 30 (7): 2183–2189. Bibcode:1991PChem..30.2183T. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(91)83610-W.

- Sedam, Michael T. (2002). The Olympic Peninsula: The Grace & Grandeur. Voyageur Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0896584587.

External links

- Picea sitchensis – information, genetic conservation units and related resources. European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN)

- Gymnosperm Database

- Arboretum de Villardebelle – photos of cones of Picea sitchensis and related spruces

- Prof Stephen Sillett's webpage with photos taken during canopy research.

- Description of Sitka Spruce in forestry (PDF) by US Department of Agriculture

- Picea Sitchinesis 'Octopus tree'