James Strangeways

Sir James Strangeways (c. 1410—1480) was Speaker of the House of Commons of England between 1461–1462.[1] and a close political ally of Edward IV's Yorkist faction.

Sir James Strangeways | |

|---|---|

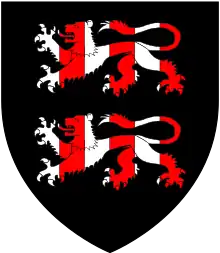

Arms of Strangways: Sable, two lions passant paly of six argent and gules | |

| Predecessor | Sir James Strangeways, knt |

| Successor | Sir Richard Strangeways, knt |

| Born | James Strangeways Harlsby, Osmotherley, Yorkshire, England |

| Buried | St Mary's Overy, Southwick [Southwark] |

| Family | Strangeways of Harlsby and Whorleton |

| wife | Elizabeth Darcy Elizabeth Eure |

| Issue | 11 sons, 4 daughters |

| Father | Sir James Strangeways |

| Mother | Anne Orrell |

| Occupation | knight Sheriff Justice of the Peace Member of Parliament |

Life

James was the son of Sir James Strangeways of Whorlton, Yorkshire appointed Chief Justice of North Wales. In London he was a King's Serjeant and then a justice of the common pleas in 1426[2] by his wife Joan, daughter of Nicholas Orrell. He was appointed High Sheriff of Yorkshire in 1446, 1453, and 1469 and was returned for the county to the parliaments of 1449 and 1460 and 1461–2.

A Yorkist, he fought at the 1st battle of St Albans in 1455, Blore Heath in 1459, and Wakefield in 1460. His career was informative during that year, at the start of which in March the Lancastrians confirmed his post as High Sheriff of the North Riding. His previous conduct might have hinted at other allegiances for in 1459 the king appointed a northern embassy to Scotland, but Strangeways refused to travel. That summer Edward, Earl of March, headed a Yorkist invasion force that marched into the Midlands. On 30 July 1460 they decisively defeated the King's army. But by that time the administration had already removed Strangeways from his post. The parliament of October 1460 was almost wholly Yorkist.

Strangeways was returned for Yorkshire with his brother-in-law, the other 'knight of the shire', Sir Thomas Montford. Reappointed as a JP of the North Riding, he rode with the Yorkist nobles into southern Yorkshire to arrest and imprison the Lancastrian knights there. Strangeways made extensive use of an arbitrary piece of law Scandalum magnatum widely abused by the Yorkist regime. It enabled the arrest for just cause for uttering alleged falsehoods, and artisans who breached patent laws in manufacture. Its application was generalised by court officials. When Somerset's army defeated and killed the duke of York at Wakefield at the end of the year the earl of March was not present. It is likely Strangeways was captured but released by Edward when he was reported as killed at the Towton on 10 May 1461. He was immediately reinstated as JP for West Riding with his son as JP for North Riding. He was charged by the charismatic soldier-king to find and imprison leading Lancastrian rebels. Dr John Morton and Sir John Conyers were leading members of Henry VI's affinity. Morton was a former Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and a senior court official. Conyers’ wife was a co-heiress to the Darcy fortune into which Strangeways had married. This was taxation by stealth, later known as Morton's Fork, one of Edward's cunning dynastic devices. The Commission of Oyer et Terminer was a State Trial that aimed at the truth about bringing lawless opponents of the regime to book through summary procedures. King Edward thanked his faithful retainer after his great victories of 1461 when the Yorkist army marched into London to announce a new reign. Edward was generous to his friends, but wrathful to those who were disloyal.

Strangeways' fealty was rewarded with Speaker of the House of Commons in the first parliament of Edward IV which met in November 1461.[3] For the first time in English history the speaker addressed the king, immediately after his presentation and allowance, in a long speech reviewing the state of affairs and recapitulating the history of the civil war. The parliament transacted hardly any business other than numerous acts of attainder against Lancastrians. It was prorogued to 6 May 1462 and then dissolved. Strangeways, who was paid 200 marks for being a 'diligent' Speaker, then served on various commissions for the defence of the kingdom and suppression of rebellions. He also sat regularly on the commissions of the peace for the North and West Ridings of Yorkshire.

With the death of the Earl of Salisbury, Strangeways drew closer to the Neville faction and Warwick the Kingmaker from 1463 onwards. He remained a northerner at heart in the fastness of Yorkshire dominated by the Neville family and its castles.[4] He held the powerful position of Chief Justice of Durham Palatinate in the Yorkist interest until the Readeption. Sir James’ second marriage was to Elizabeth Eure. An ancient Norman family, de Eure could trace their lineage through the Plantagenets, securing Strangeways immortality among the noble elites.[5] The Yorkist administration asked Strangeways to visit Scotland twice on embassy. Edward was eager to secure a mutual and profitable peace in 1464 and 1466. On the latter occasion the Scots’ delegation met Sir James and others, including his eldest son and heir, Sir Richard at New Castle on the River Tyne. His second wife made Sir James join the Guild of Corpus Christi of York to atone by religious devotions.[6]

He died in 1516[7]), and was buried in the abbey church of St. Mary Overy's, Southwark.

Family

He had married twice; firstly Elizabeth Darcy (1417–61), daughter of Sir Philip Darcy, 6th Baron Darcy of Knayth, with whom he had at least 11 sons and four daughters[8] including Robert Strangeways[5] whose daughter, Joan Strangeways, married Christopher Boynton, son of Sir Christopher Boynton (died 1452) of Sedbury,[9] and was buried at St Mary's Church, South Cowton. His second wife was Elizabeth Eure (1444-1481), daughter of Ralph, Lord Eure of Berwick Castle and a Yorkist ally, and his wife Eleanor Bulmer of Appletreewick, Yorkshire. They had at least three surviving children, Felicia, Ralph, and Edward.

Children

by his first wife

- Sir Richard, knt married 1) Elizabeth, daughter of William Neville, 1st earl of Kent; married 2) Joan, daughter of Richard de Aston.

- James of Smeton married Anne, daughter of Sir John Conyers.

- William

- Philip

- George, clerk

- Christopher

- Henry married Alinore, daughter Walter Tailboys

- John

- Robert of Ketton

- Thomas died young

- Thomas

- Margery married 1. John Ingleby 2.Richard Welles, knt, Lord Welles

- Eleanor married Edmund Mauleverer of Woodersome.

- Joan

- Elizabeth married Marmaduke Clervaux.

His grandson, also Sir James Strangeways and often confused with his grandfather, was also High Sheriff of Yorkshire in 1492 and 1508.

References

- Department of Information Services (9 July 2009). "Speakers of the House of Commons" (PDF). SN/PC/04637. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- Plea Rolls of the Court of Common Pleas; National Archives; CP 40/717; Year 1440; http://aalt.law.uh.edu/AALT1/H6/CP40no717/bCP40no717dorses/IMG_1902.htm; 4th entry as defendant against John Fastolf, knight

- Official Return of Members of Parliament, I, 340, 356, App.XXIV.; J.S. Roskell, Parliaments and Politics in Late Medieval England, II, 279.

- J.S. Roskell, The Speakers in the Commons and House of Parliament, 1376-1523, MUP, 1965, p.271.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta ancestry : a study in colonial and medieval families, Vol IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City, UT.: Douglas Richardson. p. 128. ISBN 9781460992708.

- B.Skaife, Register of the Guild of Corpus Christi in the City of York, Surtees Society, 75 (1872), 75

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Lock, Julian. "Strangways, Sir James". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26642. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta ancestry : a study in colonial and medieval families, Vol IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City, UT.: Douglas Richardson. p. 189. ISBN 9781460992708.

Bibliography

- J.S. Roskell, 'Sir James Strangeways of West Harsley and Whorlton', The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, vol.XXXIX, (1958), 455–82.

_(2022).svg.png.webp)