Household silver

Household silver or silverware (the silver, the plate, or silver service) includes tableware, cutlery, and other household items made of sterling silver, silver gilt, Britannia silver, or Sheffield plate silver. Silver is sometimes bought in sets or combined to form sets, such as a set of silver candlesticks or a silver tea set.

.jpg.webp)

Historically, silverware was divided into table silver, for eating, and dressing silver for bedrooms and dressing rooms. The grandest form of the latter was the toilet service, typically of 10-30 pieces, often silver-gilt, which was especially a feature of the period from 1650 to about 1780.

History

Elites in most ancient cultures preferred to eat off precious metals ("plate") at the table; China and Japan were two major exceptions, using lacquerware and later fine pottery, especially porcelain. In Europe the elites dined off metal, usually silver for the rich and pewter or latten for the middling classes, from the ancient Greeks and Romans until the 18th century. Another alternative was the trencher, a large flat piece of either bread or wood. In the Middle Ages this was a common way of serving food, the bread also being eaten; even in elite dining it was not fully replaced in France until the 1650s.[1]

Possession of silverware obviously depends on individual wealth; the greater the means, the higher was the quality of tableware that was owned and the more numerous its pieces. The materials used were often controlled by sumptuary laws. In the late Middle Ages and for much of the Early Modern period much of a great person's disposable assets were often in plate, and what was not in use for a given meal was often displayed on a dressoir de parement or buffet (indeed, similar to a large Welsh dresser) in the dining hall. At the wedding of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and Isabella of Portugal in 1429, there was a dresser 20 feet long on either side of the room, each with five rows of plate.[2] Inventories of King Charles V of France (r. 1364–1380) record that he had 2,500 pieces of plate.[3] Plate was often melted down to finance wars or building, and hardly any of the enormous quantities recorded in the later Middle Ages survives. The French Royal Gold Cup now in the British Museum, in solid gold and decorated with enamel and pearls, is one of few exceptions.

Maintenance

Silver requires a good deal of care, as it tarnishes and must be hand polished, since careless or machine polishing ruins the patina and can completely erode the silver layer in Sheffield plate.

A silverman or silver butler has expertise and professional knowledge of the management, secure storage, use, and cleaning of all silverware, associated tableware, and other paraphernalia for use at military and other special functions. This expertise covers the maintenance, cleaning, proper use, and presentation of these assets to create aesthetically correct layouts for effective ambience at such splendid occasions. The role of silverman tends now to be restricted to some private houses and large organizations, in particular the military.

One advantage of silverware is that growth of bacteria is inhibited by the oligodynamic effect.

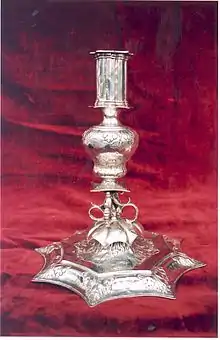

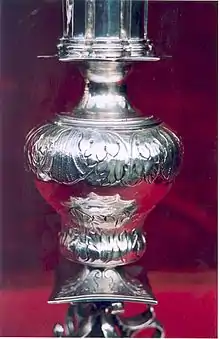

Sterling silver candlestick, One of a pair of candlesticks made for the 5th Earl of Bath's widow. Marks for silversmith Robert Cooper, London, and 1679. They bear the arms of the widow of the 5th Earl of Bath.

Sterling silver candlestick, One of a pair of candlesticks made for the 5th Earl of Bath's widow. Marks for silversmith Robert Cooper, London, and 1679. They bear the arms of the widow of the 5th Earl of Bath.

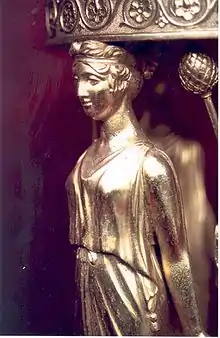

Mark of Robert Cooper

Mark of Robert Cooper De Lamerie

De Lamerie Pair of salts, salver and cream jug bearing arms of family of Beachcroft. (Arms granted 12 Nov. 1717: Bendy of siz argent and gules three stags heads cabossed or. Crest: A beech tree proper behind six park pales argent.)

Pair of salts, salver and cream jug bearing arms of family of Beachcroft. (Arms granted 12 Nov. 1717: Bendy of siz argent and gules three stags heads cabossed or. Crest: A beech tree proper behind six park pales argent.) Seven salvers (c. 1735–1750). (Arms of Bisse (granted Ireland 25 May 1637): Sable three escalops in pale argent a canton ermine and a crescent for difference or. Crest: On a mount vert two snakes or, interlaced respecting each other.)

Seven salvers (c. 1735–1750). (Arms of Bisse (granted Ireland 25 May 1637): Sable three escalops in pale argent a canton ermine and a crescent for difference or. Crest: On a mount vert two snakes or, interlaced respecting each other.) A c. 1770 hot-water jug, Dublin

A c. 1770 hot-water jug, Dublin Paul Storr

Paul Storr GS & WF canteen laid out

GS & WF canteen laid out Coburg pattern canteen

Coburg pattern canteen Detail of a teapot

Detail of a teapot Detail of GS & WF forks. George Smith III and William Fearn

Detail of GS & WF forks. George Smith III and William Fearn

See also

Notes

- Strong, 226

- Strong, 96-98. Strong says 1429, the year the proxy wedding took place. The bride arrived by sea in late 1429, but the formal marriage ceremony was not until January 1430.

- Strong, 97

References

- Strong, Roy, Feast: A History of Grand Eating, 2002, Jonathan Cape, ISBN 0224061380

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.