Sherman, Texas

Sherman is a city in and the county seat of Grayson County, Texas, United States.[5] The city's population in 2020 was 43,645.[6] It is one of the two principal cities in the Sherman–Denison metropolitan statistical area, and is the largest city in the Texoma region of North Texas and southern Oklahoma.

Sherman, Texas | |

|---|---|

Paul Brown United States Courthouse in Sherman | |

| Motto: "Classic Town. Broad Horizon." | |

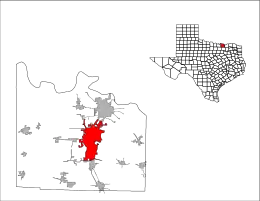

Location of Sherman, Texas | |

Sherman Location in Texas  Sherman Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 33°38′28″N 96°36′36″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Grayson |

| Founded | 1846 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • City Council | Mayor David Plyler Deputy Mayor Daron Holland Pam Howeth Shawn Teamann Josh Stevenson Juston Dobbs Henry Marroquin |

| Area | |

| • City | 46.22 sq mi (119.72 km2) |

| • Land | 46.15 sq mi (119.52 km2) |

| • Water | 0.08 sq mi (0.20 km2) |

| • Urban | 35.9 sq mi (93.1 km2) |

| • Metro | 979 sq mi (2,536 km2) |

| Elevation | 735 ft (224 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 43,645 |

| • Density | 953.56/sq mi (368.17/km2) |

| • Urban | 61,900[2] (US: 438th) |

| • Urban density | 1,722.9/sq mi (665.2/km2) |

| • Metro | 120,877 |

| • Metro density | 130/sq mi (50/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 75090-75092 |

| Area code | 903 |

| FIPS code | 48-67496[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1368131[4] |

| Website | www |

History

Sherman was named after General Sidney Sherman (July 23, 1805 – August 1, 1873), a hero of the Texas Revolution. The community was designated as the county seat by the act of the Texas Legislature, which created Grayson County on March 17, 1846. In 1847, a post office began operation. Sherman was originally located at the center of the county, but in 1848, it was moved about 3 miles (5 km) east to its current location. By 1850, Sherman had become an incorporated town under Texas law. It had also become a stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail route through Texas. By 1852, Sherman had a population of 300 and consisted of a public square with a log court house, several businesses, a district clerk's office, and a church along the east side of the square. In 1861, the first flour mill was built.

During the 1850s and 1860s, Sherman continued to develop and to participate in regional politics. Because many residents of North Texas had migrated from the Upper South and only a low percentage were slaveholders, considerable Unionist sentiment existed in the region. E. Junius Foster, the publisher of Sherman's antisecessionist Whig newspaper, the Patriot, circulated a petition to establish North Texas as an independent free state. Following Confederate passage of a conscription law, resistance arose to conscription in North Texas, especially as owners of many slaves were exempt.

A group of slaveholders in nearby Cooke County feared the Unionists might join others and perform acts of sabotage. In October 1862, a unit of state militia arrested between 150 and 200 men on suspicion of insurrection. In the Great Hanging at Gainesville, 42 of the arrested men were killed, most of them hanged by a mob, while others were sentenced to death by a self-appointed "citizens' court". Following the lynchings, Colonel William Young, who had organized the jury for the "citizens' court", was killed by unknown assailants. Young had been responsible for more than 20 deaths. Newspaper publisher Foster "applauded" Young's death, and was soon gunned down by Capt. Jim Young, the colonel's son.[7]

Pro-Confederate militiamen rounded up even more "suspects" in Sherman, but Confederate Brigadier General James W. Throckmorton intervened to stop the killings. By the time Throckmorton restored order, only five of the originally arrested men were still alive.[7]

Late in the Civil War, pro-Confederate guerrillas led by William Quantrill spent the winter in Sherman. Former guerrilla Jesse James also came to Sherman for his honeymoon. He was photographed seated on his horse in Sherman.

During the 1860s, secondary education developed in North Texas. The Sherman Male and Female High School began accepting students in 1866, under the patronage of the North Texas Methodist Conference. It became one of three private schools operating in Sherman. The school operated under several names, including the North Texas Female College and Conservatory of Music from 1892 to 1919 and Kidd-Key College and Conservatory, from 1919 to 1935.[8] It gradually lost Methodist support, following the opening of Southern Methodist University in Dallas in 1915. In 1876, Austin College, the oldest continuously operating college in Texas, was relocated to Sherman from Huntsville. The Sherman Female Institute, later called Mary Nash College,[9] opened in 1877 under sponsorship of the Baptist Church. It continued to operate until 1901, when the campus was sold to Kidd-Key College. Carr–Burdette College, a women's college affiliated with the Disciples of Christ, operated from 1894 to 1929. Sherman also has a long history within the Jewish community. By 1873, Jews in the region regularly met for the High Holidays.[10]

While general depression and lawlessness occurred during the Reconstruction, Sherman remained commercially active. During the 1870s, Sherman's population reached 6,000. In 1875, after two fires destroyed many buildings east of the town square, a number of civic buildings were rebuilt using more permanent materials. This included a new Grayson County Courthouse built in 1876. In 1879, the Old Settlers' Association of North Texas formed and met near Sherman. The organization incorporated in 1898 and purchased Old Settlers' Park in 1909.

On May 15, 1896, a tornado measuring F5 on the Fujita scale struck Sherman. The tornado had a damage path 400 yards (370 m) wide and 28 miles (45 km) long, killing 73 people and injuring 200. About 50 homes were destroyed, with 20 of them obliterated.

In 1901, the first electric "Interurban" railway in Texas, the Denison and Sherman Railway, was completed between Sherman and Denison.[11] The Texas Traction Company completed a 65-mile (105 km) interurban between Sherman and Dallas in 1908, and in 1911 purchased the Denison and Sherman Railway. Through the connections in Dallas and Denison, travel to the Texas destinations of Terrell, Corsicana, Waco, Fort Worth, Cleburne, and Denton, became possible, as well as to Durant, Oklahoma, by interurban railways. One popular destination on the Interurban between Sherman and Denison was Wood Lake Park, a private amusement park at the time. By 1948, all interurban rail service in Texas had been discontinued.

Sherman Riot of 1930

During the Sherman Riot of May 9, 1930,[12] the Grayson County Courthouse was burned down by local citizens in an attempt to lynch George Hughes, an African American suspected of assaulting a white woman.[13] During the riot, Hughes was locked in the vault at the courthouse and apparently died in the fire.[14] Rescue work was hindered by saboteurs cutting the fire hoses. After rioters retrieved Hughes' body from the vault, it was dragged behind a car, hanged, and set afire. The black business section of Sherman was also burned down, and many African Americans fled. Texas Ranger Frank Hamer was in Sherman during this riot, and reported the situation to Texas Governor Dan Moody.[15] Governor Moody sent National Guard troops to Sherman on May 9 and martial law was declared in Sherman for ten days.[13] Fourteen men were later indicted, not for lynching, but for arson and rioting. In the end, only J.B. "Screw" McCasland was convicted and sentenced to prison for arson[16] and for rioting.[17][12]

Geography

Sherman is located slightly east of the center of Grayson County, between Denison to the north and Howe to the south. The city has a total area of 41.5 square miles (107.4 km2), of which 41.4 square miles (107.2 km2) are land and 0.1 square miles (0.2 km2), or 0.20%, is covered by water.[6]

Sherman is 70 miles (110 km) north of Dallas[18] and 31 miles (50 km) southwest of Durant, Oklahoma. Gainesville is 32 miles (51 km) to the west, and Bonham is 26 miles (42 km) to the east.

Climate

Sherman is part of the humid subtropical climate area.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 35 | — | |

| 1860 | 613 | 1,651.4% | |

| 1870 | 1,439 | 134.7% | |

| 1880 | 6,093 | 323.4% | |

| 1890 | 7,335 | 20.4% | |

| 1900 | 10,243 | 39.6% | |

| 1910 | 12,412 | 21.2% | |

| 1920 | 15,031 | 21.1% | |

| 1930 | 15,713 | 4.5% | |

| 1940 | 17,156 | 9.2% | |

| 1950 | 20,150 | 17.5% | |

| 1960 | 24,988 | 24.0% | |

| 1970 | 29,061 | 16.3% | |

| 1980 | 30,413 | 4.7% | |

| 1990 | 31,601 | 3.9% | |

| 2000 | 35,082 | 11.0% | |

| 2010 | 38,521 | 9.8% | |

| 2020 | 43,645 | 13.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[19] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 24,248 | 55.56% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 4,473 | 10.25% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 490 | 1.12% |

| Asian (NH) | 1,387 | 3.18% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 24 | 0.05% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 134 | 0.31% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 2,310 | 5.29% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 10,579 | 24.24% |

| Total | 43,645 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 43,645 people, 15,687 households, and 10,097 families residing in the city.

Government

Sherman operates under a council-manager form of local government, and is a home rule city under Texas state law. As of 2022, the city was led by City Manager Robby Hefton and Mayor David Plyler.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice operates the Sherman District Parole Office in Sherman.[23]

Education

Public schools

Most children in Sherman are zoned to the Sherman Independent School District, which includes Sherman High School. Some parts are in Denison Independent School District or Howe Independent School District.

Private schools

A small percentage of children attend one of the three private schools in Sherman: Grayson Christian School, St. Mary's Catholic School, or Texoma Christian School.

Colleges and universities

Austin College, a private, Presbyterian, liberal arts college, relocated to Sherman in 1876. Founded in 1849, it is the oldest college or university in Texas operating under its original charter. Grayson College, a community college based in neighboring Denison, operates a branch campus in Sherman.

Libraries

The Sherman Public Library serves the city of Sherman and all citizens. The library underwent a $2 million, floor-to-ceiling renovation in 2017, reopening to the public in August 2018.

Media

Magazine

- Texoma Living! magazine[24]

Newspaper

Radio stations

Infrastructure

.jpg.webp)

Transportation

U.S. Highway 75 Oklahoma to Dallas

U.S. Highway 75 Oklahoma to Dallas U.S. Highway 82 east-west: Georgia to New Mexico

U.S. Highway 82 east-west: Georgia to New Mexico SH 56 east-west: Honey Grove to Whitesboro

SH 56 east-west: Honey Grove to Whitesboro SH 91 north-south: Achille, Oklahoma to Sherman

SH 91 north-south: Achille, Oklahoma to Sherman SH 11 east-west: Linden to Sherman

SH 11 east-west: Linden to Sherman FM 1417 north-south: Denison to Sherman

FM 1417 north-south: Denison to Sherman FM 691 east-west: Sherman to North Texas Regional Airport

FM 691 east-west: Sherman to North Texas Regional Airport FM 131 north-south: Denison to Sherman

FM 131 north-south: Denison to Sherman FM 697 east-west: Whitewright to Sherman

FM 697 east-west: Whitewright to Sherman

Sherman is served by two U.S. Highways: US 75 (Sam Rayburn Freeway) and US 82. (The latter is locally designated as the Buck Owens Freeway after the famous musician who was born in Sherman.) It is also served by three Texas State Highways, which extend beyond Grayson County: State Highway 11, State Highway 56, and State Highway 91 (Texoma Parkway), one of the main commercial strips that connects Sherman and Denison, and also extends to Lake Texoma.

General aviation service is provided by Sherman Municipal Airport and North Texas Regional Airport/Perrin Field in Denison.

TAPS Public Transit is the sole transit provider for Sherman, with curb-to-curb paratransit for all residents.[25]

Medical care

The city of Sherman is served locally by Wilson N. Jones Regional Medical Center, Texoma Medical Center, and a Baylor Scott & White surgery center.

Top employers

- Tyson Foods

- Texas Instruments

- II-VI Incorporated

- Grayson County

- City of Sherman

- Cooper B-Line Systems

- Austin College

- Fisher Controls/ Emerson Process Management

- Kaiser Aluminum

- Presco Products

- Progress Rail

- Consolidated Containers

- Plyler Construction

- Starr Aircraft

- Douglass Distributing

- GlobiTech

- Sunny Delight Beverages

Notable people

See also

Notes

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Census of Urban areas

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Census - Geographic Profile: Sherman city, Texas". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- McCaslin, Richard B. "Great Hanging of Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "Kidd-Key College", (accessed March 18, 2007)

- Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "Mary Nash College", (accessed March 18, 2007)

- "Sherman/Denison, Texas" Archived 2012-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, found in the Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities,

- Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "Electric Interurban Railways" (accessed March 31, 2007)

- Thompson, Nolan Herman (1995). "Sherman Riot of 1930". Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 4, 2015 (uploaded June 15, 2010; modified February 7, 2014).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) OCLC 54906271 (all editions) (online), 259977569, 1048555490, 3095662, 560142789. - Bills, E. R. (né Eddie Ray Bills II) (2015). Black Holocaust: The Paris Horror and a Legacy of Texas Terror. Fort Worth: Eakin Press. Charleston: The History Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) ISBN 978-1-6817-9017-6, 1-6817-9017-3; OCLC 922702180 (all editions). - Bills, E.R. (2007). "9. Sherman Riot". Texas Far & Wide: "The Tornado With Eyes" – "Gettysburgs Last Casualty" – "The Celestial Skipping Stone" – and Other Tales. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-6305-9.

- Statement of Frank Hamer on May 13, 1930 (accessed March 6, 2007)

- Dallas Morning News, The (June 5, 1931). "McCasland Gets Two-Year Term in First of Sherman Riot Trials – Is Convicted of Arson of Burning Courthouse – Lynching Ignored". Vol. 46, no. 248. pp. 1, 12 (section 1). Retrieved June 8, 2021 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- Fredericksburg Standard (July 3, 1931). "Sherman Rioter Given Two Years". Vol. 21, no. 41. Fredricksburg, Texas. p. 6. Retrieved June 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. LCCN sn86089412 ; OCLC 14279865.

- Google Maps

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- https://www.census.gov/

- "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- "Parole Division Region II Archived 2011-08-20 at the Wayback Machine." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on May 15, 2010.

- "Search every page of every issue published by Texoma Living! Magazine from 2006 to 2010". Texoma Living! Online. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "TAPS Public Transit". Retrieved August 7, 2018.

Further reading

- Grayson County Frontier Village, The History of Grayson County Texas, Hunter Publishing Co., Winston-Salem, North Carolina, 1979.

- Redshaw, Peggy A., "Sherman, Texas, and the 1918 Pandemic Flu," East Texas Historical Journal, 51 (Spring 2013), 67–85.

- E. R. Bills (author). Black Holocaust: The Paris Horror and a Legacy of Texas Terror. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015.