Scleroderma citrinum

Scleroderma citrinum, commonly known as the common earthball,[1] pigskin poison puffball,[2] or common earth ball,[3] is the most common species of earthball in the UK and occurs widely in woods, heathland and in short grass from autumn to winter. Scleroderma citrinum has two synonyms, Scleroderma aurantium (Vaill.) and Scleroderma vulgare Horn.[4]

| Scleroderma citrinum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Boletales |

| Family: | Sclerodermataceae |

| Genus: | Scleroderma |

| Species: | S. citrinum |

| Binomial name | |

| Scleroderma citrinum | |

| Scleroderma citrinum | |

|---|---|

| Glebal hymenium | |

| No distinct cap | |

| Hymenium attachment is not applicable | |

| Lacks a stipe | |

| Spore print is purple-black | |

| Ecology is mycorrhizal | |

| Edibility is poisonous | |

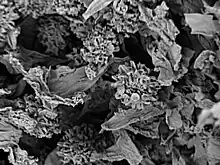

Earthballs are superficially similar to, and considered look-alikes of, the edible puffball (particularly Apioperdon pyriforme), but whereas the puffball has a single opening on top through which the spores are dispersed, the earthball just breaks up to release the spores. Moreover, Scleroderma citrinum has much firmer flesh and a dark gleba (interior) much earlier in development than puffballs. Scleroderma citrinum has no stem but is attached to the soil by mycelial cords. The peridium, or outer wall, is thick and firm, usually ochre yellow externally with irregular warts.

The earthball may be parasitized by Pseudoboletus parasiticus.

Scleroderma citrinum can be mistaken with truffles by inexperienced mushroom hunters. Ingestion of Scleroderma citrinum can cause gastrointestinal distress in humans and animals. Some individuals may experience lacrimation, rhinitis and rhinorrhea, and conjunctivitis from exposure to its spores.[5][6]

Pigments found in the fruiting body of Scleroderma citrinum Pers. are sclerocitrin, norbadione A, xerocomic acid, and badione A.

Notes

- "List of Recommended English Names For Fungi in the UK." Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine (Website.) Fungi 4 Schools, by the British Mycological Society. Retrieved on 2007-09-17.

- (January 2005.) "Oxbow National Wildlife Refuge: Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan, January 2005." U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, p. 195, via library.fws.gov. Retrieved on 2007-09-17.

- Falandysz J (March 2002). "Mercury in mushrooms and soil of the Tarnobrzeska Plain, south-eastern Poland". J Environ Sci Health a Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 37 (3): 343–52. doi:10.1081/ese-120002833. PMID 11929073. S2CID 24124204.

- Pekşen, Aysun and Gürsel Karaca (2003). "Macrofungi of Samsun Province" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Botany. 27: 173–184.

- (October 2006.) "Reflections on Mushroom Poisoning – Part III." (Newsletter.) Fungifama: The Newsletter of the South Vancouver Island Mycological Society, via svims.ca. Retrieved on 2007-09-17.

- Hoffman, Ursula. "Poisonous Mushrooms in Northeastern North America" Archived 2004-06-07 at the Wayback Machine (Website.) NorthEast Mycological Federation, Inc. Retrieved on 2007-09-17.

References

- Buckzacki, Stefan; John Wilkinson (1982). Mushrooms and Toadstools (Collins Gem Guide). Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-00-458812-6.

- Wakefield, Elsie M. (1964). The Observer's Book of Common Fungi (Observer's Pocket Series No. 19) (3rd printing ed.). Frederic Warne & Co Ltd. OCLC 748994120.

External links

- Medicinal Mushrooms Description, bioactive compounds, medicinal properties

- Mushroom Expert Additional information