Sayyid Hassan Ali Khan Barha

Nawab Sayyid Hassan Ali Khan Barha (1666 – 12 October 1722), also known as Qutub-ul-Mulk, Nawab Sayyid Mian II, Abdullah Khan II, was one of the Sayyid Brothers, and a key figure in the Mughal Empire under Farrukhsiyar.

| Nawab Sayyid Abdullah Khan II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nawab of Ajmer, Allahabad and Bihar | |||||

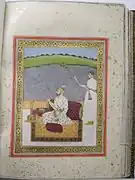

Nawab Syed Hassan Ali Khan Barha smoking a shish pipe while being attended to by a servant | |||||

| Ajmer | |||||

| Reign | 1710 – 13 November 1720 | ||||

| Predecessor | Abdullah Khan I | ||||

| Successor | Nawab Sayyid Najmudin Ali Khan | ||||

| Allahabad | |||||

| Predecessor | Shah Qudratullah of Allahabad | ||||

| Successor | Sarbuland Khan | ||||

| Born | Hassan Ali Khan 1666 Jansath | ||||

| Died | 12 October 1722 (aged 55–56) Delhi | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| |||||

| House | Barha Dynasty | ||||

| Father | Abdullah Khan I | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

| Occupation | Wazir-e-Azam and Sipahsalar | ||||

He was the eldest son of the Nawab of Ajmer, Sayyid Mian Abdullah Khan I and later inherited his father's titles as well as the name Abdullah Khan but was also frequently referred to as Qutb al mulk, "Pivot of the Realm". Deposing emperors at their own will, both Abdullah Khan and his brother Hussain Ali Khan become the most powerful figures in early 18th century Mughal court.[1]

Ancestry

Abdullah Khan was a member of the Barha Dynasty. The meaning of the name Barha is uncertain. While some contend that it comes from the word, "bahir", meaning "outsider" referring to the preference of members of the Barha dynasty to live outside Delhi. Others like the Emperor Jahangir, believed that it came from the Hindi word, "barha", meaning "twelve". In reference to the twelve townships that members of the dynasty had received as fiefs from Sultan Shibabdudin of Ghor when they first arrived in India.[2]

The dynasty descends in the male line from the fourth Rashidun Caliph, Ali, through his younger son Hussain who married Shahrbanu, herself a daughter of the Sassanian Emperor of Persia, Yazdegard III. Due to Ali's status as an Adnanite, the dynasty can trace its ancestry to Abraham through his eldest son Ishmael.[3]

In Arabia, Abdullah Khan's ancestors took part in many rebellions against the authority of the Abbasid Caliphate. One ancestor, Isa bin Zayd, revolted against the Caliph Al Mahdi and was consequently poisoned by that caliph at the age of 45. Subsequently, the dynasty were heavily persecuted by the Abbasid government, and eventually the founder of the Barha dynasty, Abul Farah Al Wasiti, fled from Madina to Wasit and from there he fled to the Ghaznavid Empire. His four sons entered into the military service of Sultan Muhammad of Ghor and received twelve fiefdoms in Punjab, then a part of the Ghor Empire, as reward for their service. Thus the dynasty became quickly established as Nobles of the Sword in ancient India, a status they held under several different empires. They held a particularly high status under the Sultanate of Delhi. When the Chief of the Barha, who was also the Diwan of the empire, was granted the fiefdom of Saharanpur due to his relation with the imperial family.[4] They also enjoyed particularly prominent positions under the reign of the Sur, eventually defecting during the last days in the reign of Sikander Sur of the Sur Empire, to the Emperor Akbar of the Mughal Empire in the course of the siege of Mankot.[5][6]

Barha claim of Sayyid lineage was not accepted by their contemporaries. Emperor Jehangir remarked that "some people make remarks about their lineage, but their bravery is a convincing proof of their being Sayyids." They were said to be descendants of Punjabi farmers who migrated to Muzaffarnagar.[7][8]

The Barha dynasty maintains the unique status of having been the only dynasty to participate in all three Battles of Panipat, seminal battles which shaped Indian History. Under the Lodi in the First Battle of Panipat. In the Second Battle of Panipat they gained victory under Bairam Khan, and finally in the Third Battle Of Panipat, the sons of Nawab Ali Muhammad Khan Rohilla fought with Ahmed Shah Abidali against the Maratha.

By the time of the Emperor Aurangzeb, the dynasty was firmly regarded as "Old Nobility" and enjoyed the unique status of holding the premier realms of Ajmer and Dakhin. Realms usually reserved for the rule of members of the Imperial Family.[9]

Biography

Barha was one of the main backers of Farrukhsiyar's rise to the throne. He initially served as Bakshi for the empire but later rose to become the Vezier or Prime Minister. He was additionally made the Nawab of Bihar which he ruled though proxy. Abdullah Khan and his brother Hussain Ali Khan restored Mughal authority to Ajmer in Rajasthan with the surrender of Maharaja Ajit Singh, and Abdullah Khan negotiated the surrender of the Jat rebel Churaman.[10] During their rule, the Sikh rebel Banda Singh Bahadur was also captured and executed. The Sayyid faction at court were a powerful family rule that was linked together by ties of blood and marriage. The Sayyids engaged in recruitment of soldiers very few who were not Sayyids, or inhabitants of Barha, or were non-Muslims.[11] This distinguished them from their rivals, as it gave them greater strength and cohesion. The unique privilege of the Barha Sayyids of leading the imperial vanguard gave them an advantage over other parts of the Mughal army, and exalted the sense of social pride of the Barha Sayyids. The arrogance of the Sayyid brothers during their rule as they grew in power aroused the jealousy of the king and other nobles in the court. However, the emperor Farrukhsiyar failed in all his attempts to dislodge Sayyid rule.[12]

Over the course of his life. Abdullah Khan Barha had a hand in the installation or deposition of the Emperors: Bahadur Shah I,[13] Jahandar Shah,[14] Farrukhsiyar, Rafi Ud Darajat, Shah Jahnan II, Muhammad Shah[15] and Ibrahim.[16]

Upon the assassination of his brother, Nawab Sayyid Hussain Ali Khan Barha by Turani nobles through the assassin Mirza Haider Dughlat of the Mongol Dughlat tribe,[17] he led an army against the Emperor Muhammad Shah with his own puppet Emperor, Ibrahim. After large swathes of his own army deserted him, Abdullah Khan personally fought on foot following the Barha tradition and was captured by the Emperor. Sayyid Abdullah Khan remained a prisoner in the citadel of Delhi, under the charge of Haider Quli Khan, for another two years. He was "treated with respect, receiving delicate food to eat and fine clothes to wear". But so long as he survived, the Mughals remained uneasy, not knowing what sudden change of fortune might happen. Thus the nobles never ceased their efforts in alarming Muhammad Shah.[18] In order to reduce the power of the Turani nobles, Muhammad Shah thought of using the services of Qutb-ul-Mulk after setting him free and raising him to a high mansab. He sent a message to Qutb-ul-Mulk in this regard and received an encouraging reply from him. However, on hearing of this overture made by Muhammad Shah to Qutb-ul-Mulk and fearing the dire implications thereof, Qutb-ul-Mulk's opponents had him poisoned to death on 12 October 1722.[19]

Depictions

Qutb-ul-Mulk Sayyid Hassan Ali Abdullah Khan

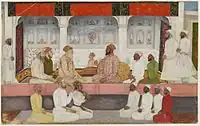

Qutb-ul-Mulk Sayyid Hassan Ali Abdullah Khan_-_2013.334_-_Cleveland_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Abdullah Khan (Gold Cummerbund) with his brothers. Seated opposite his younger brother Nawab Hussain Ali Khan Barha (without a cummerbund).

Abdullah Khan (Gold Cummerbund) with his brothers. Seated opposite his younger brother Nawab Hussain Ali Khan Barha (without a cummerbund). Sayyid Abdullah Khan Barha holding court

Sayyid Abdullah Khan Barha holding court Abdullah Khan as Grand Vizier of the Mughal Empire

Abdullah Khan as Grand Vizier of the Mughal Empire A young Abdullah Khan as governor of Allahbad during the reign of Bahadur Shah I

A young Abdullah Khan as governor of Allahbad during the reign of Bahadur Shah I

Sources

- John F. Richards. New Cambridge History of India: The Mughal Empire. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993. p. 264–268.

References

- Angus, Maddison (2003-09-25). Development Centre Studies the World Economy Historical Statistics: Historical Statistics. ISBN 978-92-64-10414-3.

- Nevill, H.R. (1920). "Muzaffarnagar Imperial Gazetteer". District Gazeiters of the United Provinces of Aga and Oudh. III.

- Abul Fazl (2004) [c. 1590]. Phillott, Douglas Craven (ed.). The Āʼīn-i Akbarī. Translated by Blochmann, Henry (2nd ed.). Sang-e-Meel Publications. ISBN 9693515307.

- Sirhindi, Yahya (2010). Tareek-e-Mubarak Shahi. ISBN 978-8175365056.

- Kazim, Syed (2000). "A critical study of the role and achievements of Sayyid brothers". Shodhganga: 22. hdl:10603/52425.

- Khan, Reaz Ahmed. "Afghans and Shaikhzadas in the nobility of Shah Jahan". Shodhganga: 15.

- Atkinson, Edwin Thomas (1876). Statistical, Descriptive and Historical Account of the North-Western Provinces of India: 3.:Meerut division part 2. North-Western Provinces Government. p. 590.

- H.A., Kolff, Dirk (8 August 2002). Naukar, Rajput, and sepoy : the ethnohistory of the military labour market in Hindustan, 1450-1850. ISBN 0-521-52305-2. OCLC 995477816.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Irvine, William (August 2012). The Later Mughals. p. 203. ISBN 978-1290917766.

- Krishna S. Dhir (2022). The Wonder That Is Urdu. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 119. ISBN 9788120843011.

- Abdul Aziz (1964). Discovery of Pakistan. the University of Michigan. p. 136.

- Zahiruddin Malik (1977). The Reign Of Muhammad Shah 1919-1748.

- Irvine, William (August 2012). The Later Mughals. p. 204. ISBN 978-1290917766.

- Irivine, William (2006). The later Mughals. Low Price Publications. p. 205. ISBN 8175364068.

- Kazim, Syed (2008). "A critical study of the role and achievements of Sayyid brothers". University. hdl:10603/57016.

- "Past Present: King makers". DAWN.COM. 1 November 2009.

- Journal and Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal:Volume 4. Asiatic Society. 1910.

- S.R. Sharma (1999). Mughal Empire in India: A Systematic Study Including Source Material · Volume 1. Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 675.

- Muhammad Umar (1998). Muslim Society in Northern India During the Eighteenth Century. the University of Michigan. p. 280. ISBN 9788121508308.