Sámi Parliament of Norway

The Sámi Parliament of Norway (Norwegian: Sametinget, Northern Sami: Sámediggi [ˈsaːmeˌtiɡːiː], Lule Sami and Pite Sami: Sámedigge, Ume Sami: Sámiediggie, Southern Sami: Saemiedigkie, Skolt Sami: Sääʹmteʹǧǧ) is the representative body for people of Sámi heritage in Norway. It acts as an institution of cultural autonomy for the Sami people of Norway.

Sámi Parliament in Norway Northern Sami: Sámediggi Lule Sami: Sámedigge Pite Sami: Sámedigge Ume Sami: Sámiediggie Southern Sami: Saemiedigkie Skolt Sami: Sääʹmteʹǧǧ Norwegian: Sametinget | |

|---|---|

| 9th Sámi Parliament | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Founded | 9 October 1989 |

| Preceded by | Norwegian Sámi Council |

| Leadership | |

Speaker | |

Deputy speaker | |

President of the Sámi Parliament | |

| Structure | |

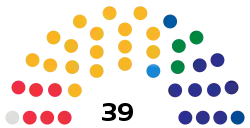

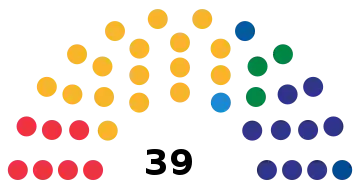

| Seats | 39 |

| |

Political groups | Governing Council (21)

Opposition (18)

|

| Elections | |

| Open list proportional representation Modified Sainte-Laguë method | |

Last election | 13 September 2021 |

Next election | September 2025 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Sámi Parliament of Norway Building Karasjok, Norway | |

| Website | |

| www | |

.jpg.webp)

The parliament opened on 9 October 1989 and its seat is in the village of Kárášjohka (Karasjok) in Kárášjohka Municipality in Troms og Finnmark county. It currently has 39 representatives, who are elected every four years by direct vote from 7 constituencies. The last election was in 2021. Unlike the neighboring Sámi Parliament of Finland, the 7 constituencies cover the entire country. The current president is Silje Karine Muotka who represents the Norwegian Sámi Association.[1]

History

.jpg.webp)

In 1964, the Norwegian Sámi Council was established to address Sámi matters. The members of the body were appointed by state authorities. This body was replaced by the Sámi Parliament.

In 1978, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate published a plan that called for the construction of a dam and hydroelectric power plant that would create an artificial lake and inundate the Sámi village of Máze. This plan was met by strong opposition from the Sámi, and resulted in the Alta controversy. As a result of the controversy, the Norwegian government held meetings in 1980 and 1981 with a Sámi delegation appointed by the Norwegian Sámi Association, the Sámi Reindeer Herders’ Association of Norway and the Norwegian Sámi Council. The meetings resulted in the establishment of a committee to discuss Sámi cultural issues, and the Sámi Rights Committee addressing Sámi legal relations. The latter proposed a democratically elected body for the Sámi, resulting in the Sámi Act of 1987. In addition, the Sámi Rights Committee resulted in the 1988 amendment of the Norwegian Constitution, and the adoption of the Finnmark Act in 2005.[2]

.jpg.webp)

The Sámi Act (1987:56),[3] stipulating the responsibilities and powers of the Norwegian Sámi Parliament, was passed by the Norwegian Parliament on 12 June 1987 and took effect on 24 February 1989. The first session of the Sámi Parliament was convened on 9 October 1989 and was opened by King Olav V.

Organization

The Norwegian Sámi Parliament plenary (dievasčoahkkin) has 39 representatives elected by direct vote from 7 constituencies. The plenary is the highest body in the Sámi Parliament and it is sovereign in the execution of the Sámi Parliaments duties within the framework of the Sámi Act. The representatives from the largest party (or from a collaboration of parties) form a governing council (Sámediggeráđđi), and selects a president. Although the position of vice-president was formally removed from the Sámi Parliament's Rules of Procedure in 2013, it is considered the concern of the President of the Sámi Parliament whether he or she wants to appoint a vice-president. The governing council is responsible for executing the roles and responsibilities of the parliament between plenary meetings. In addition there are multiple thematic committees addressing specific cases.[4]

Presidents

| Name (Birth-Death) |

Portrait | Elected | Took office | Left office | Political party | Council(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ole Henrik Magga (1947–) |

_(cropped).jpg.webp) |

1989 1993 |

9 October 1989 |

8 October 1997 |

Norwegian Sámi Association | Magga |

| 2 | Sven-Roald Nystø (1956–) |

.jpg.webp) |

1997 2001 |

8 October 1997 |

20 October 2005 | Norwegian Sámi Association | Nystø |

| 3 | Aili Keskitalo (1968–) |

|

2005 | 20 October 2005 | 26 September 2007 | Norwegian Sámi Association | Keskitalo I NSR–Sp–SfP–JSL–SSN |

| 4 | Egil Olli (1949–) |

_(cropped).jpg.webp) |

– 2009 |

26 September 2007 | 16 October 2013 | Labour Party | Olli I Ap |

| Olli II Ap–Árja–NKF–ÅAsG–SSN | |||||||

| 5 | Aili Keskitalo (1968–) |

|

2013 | 16 October 2013 | 8 December 2016 | Norwegian Sámi Association | Keskitalo II NSR |

6 |

Vibeke Larsen (1971–) |

_(10328123535).jpg.webp) |

– | 8 December 2016 | 12 October 2017 | Labour Party | Larsen Ap–H–Árja |

| Independent | |||||||

| 7 | Aili Keskitalo (1968–) |

_(37058259423).jpg.webp) |

2017 | 12 October 2017 | 21 October 2021 | Norwegian Sámi Association | Keskitalo III NSR–Sp–JSL–ÅAsG |

| 8 | Silje Karine Muotka (1975–) |

_(37470969540).jpg.webp) |

2021 | 21 October 2021[1] | Incumbent | Norwegian Sámi Association | Muotka NSR–Sp–JSL |

Location

The Sámi Parliament of Norway is located in Karasjok (Kárášjohka), and the building was inaugurated on 2 November 2000. There are also offices in Guovdageaidnu (Kautokeino), Unjárga (Nesseby), Gáivuotna (Kåfjord), Romsa (Tromsø), Skánik (Evenskjær) Ájluokta (Drag), Aarborte (Hattfjelldal) and Snåase (Snåsa).

The town of Kárášjohka is considered an important center of Sámi culture in Norway. Approximately 80% of the town's population is Sámi-speaking, and the town also hosts Sámi broadcasting stations and several public and private Sámi institutions such as the Sámi Museum and the organization Sami Trade and Industry.[5][6]

Building

The building was designed by the architects Stein Halvorsen & Christian Sundby, who won the Norwegian government's call for projects in 1995, and inaugurated in 2005. The government called for a building such that "the Sami Parliament appears in a dignified way" and "reflects Sami architecture." Hence the peaked structure of the Plenary Assembly Hall resembles the tipis the Sámi used as a nomadic culture. The parliament building also houses a Sámi library focusing on books in the Sámi language or on Sámi topics, and the Sámi chamber of commerce, Sámi Trade and Industry'.[7][8]

Responsibilities

The parliament works with political issues it considers relevant or of interest to the Sámi people. The responsibilities of the Sámi Parliament in Norway are: "(1) to serve as the Sámi’s elected political body to promote political initiatives and (2) to carry out the administrative tasks delegated from national authorities or by law to the Sami Parliament.".[4]

The extent of responsibility that was assigned and transferred from the Norwegian government at the time of establishment was modest (1989). However, more responsibilities have been added including:[9]

- Management of the Sámi Development Fund, which is used for grants to Sami organizations and Sami duodji (1989).

- Responsibility for the development of the Sámi language in Norway, including allocation of funds to Sámi language municipalities and counties (1992).

- Responsibility for Sámi culture, including a fund from the Norwegian Council for Cultural Affairs (1993).

- Protection of Sámi cultural heritage sites (1994).

- Development of Sámi teaching aids, including allocation of grants for this purpose (2000).

- Election of 50% of the members to the board in the Finnmark Estate (2006).

One of the responsibilities is ensuring that the section 1–5 of the Saami Act (1987:56)[3] is upheld, i.e., that the Sámi languages and Norwegian continue to have the same status.

Finances

Funding

Funding is granted by the Norwegian state over various national budget lines. But the parliament can distribute the received funds according to its own priorities. In the Norwegian government the main responsibility for Sámi affairs, including the allocation of funds, is the Ministry of Local government.[4]

Salaries and other expenses

The president's salary is 80% of that of the members of the Norwegian cabinet. The salary of the other 4 members of the Sámediggeráđđi (governing council) is 75% of the president's salary. The speaker's salary is 80% of the president's.[10]

Elections

To be eligible to vote or be elected to the Norwegian Sámi Parliament a person needs to be included in the Sámi Parliament’s electoral roll. In order to be included the following criteria must be met as stipulated in Section 2–6 of the Sámi Act: "Everyone who declares that they consider themselves to be Sámi, and who either has Sámi as his or her home language, or has or has had a parent, grandparent or great-grandparent with Sámi as his or her home language, or who is a child of someone who is or has been registered in the Sámi Parliament’s electoral roll, has the right to be enrolled in the Electoral roll of the Sámi Parliament in the municipality of residence."[4] Results of the last election:

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | Seats | ||||

| # | % | ± | # | ± | ||

| Norwegian Sámi Association (NSR) | 4,414 | 31.9% | +3.8% | 17 | -1 | |

| Nordkalottfolket (NKF) | 2,529 | 18.3% | +11.7% | 9 | +6 | |

| Labour Party (Ap) | 2,081 | 15.0% | -2.0% | 7 | -2 | |

| Centre Party (Sp) | 1,326 | 9.6% | +2.0% | 3 | +1 | |

| Sámi People's Party (SfP) | 772 | 5.6% | +3.6% | 1 | +0 | |

| Árja | 738 | 5.3% | -2.4% | 0 | -1 | |

| Progress Party (FrP) | 660 | 4.8% | -2.7% | 1 | 0 | |

| Conservative Party (H) | 596 | 4.3% | -2.1% | 0 | -1 | |

| Ávjovári Moving Sámi List (JSL) | 329 | 2.4% | -0.1% | 1 | +0 | |

| People's Federation of the Saami (SFF) | 200 | 1.4% | -0.3% | 0 | +0 | |

| Ávjovári Residents List (FABL) | 189 | 1.4% | -0.1% | 0 | -1 | |

| Totals | 14,084 | 100.0 | – | 39 | ±0 | |

| Blank and invalid votes | 296 | – | – | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 20,541 | 68.6 | -1.7 | – | – | |

| Source: valgresultat.no | ||||||

Cooperation with the state government

.jpg.webp)

In the Norwegian central administration the coordinating organ and central administrator for Sámi issues is the Department of Sámi and Minority Affairs in the Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion. This department also coordinates inter-ministerial and Nordic state cooperation regarding Sámi issues. The Sámi Parliament is consulted when state government issues affect Sámi interests.[11]

See also

References

- "Keskitalo guodá – Muotká joarkká". NRK Sápmi (in Lule Sami). 21 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Lovdata - Sender deg til riktig side". Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- "The respond by the Sami Parliament of Norway on the UNPFII Questionnaire 2016" (PDF). Un.org. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- "The Town with the Sami Parliament", Cristian Uluru, 2006.

- See the Wikipedia article on Kárášjohka.

- "Parliament for the Sami people", SH arkitekter, on the Modern Architectural Concepts blog, consulted 3 November 2010

- "Norway’s Sami Parliament: Getting to 50-50" Archived 2011-07-28 at the Wayback Machine, on the International Museum of Women website, consulted 3 November 2010.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Sametingets budsjett 2019, punkt 13. (17th of January 2019). Sametinget. Read on the 18th of May 2019 at sametinget.no

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

- Official site

- On gender balance in the parliament : Norway’s Sámi Parliament: Getting to 50-50, on the International Museum of Women website