Tamil Jain

Tamil Jains (Tamil Samaṇar, from Prakrit samaṇa "wandering renunciate") are ethnic-Tamils from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, who practice Jainism, chiefly the Digambara school (Tamil Samaṇam). The Tamil Jain is a microcommunity of around 85,000 (around 0.13% of the population of Tamil Nadu), including both Tamil Jains and north Indian Jains settled in Tamil Nadu. They are predominantly scattered in northern Tamil Nadu, largely in the districts of Tiruvannamalai, Kanchipuram, Vellore, Villupuram, Ranipet and Kallakurichi. Early Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions in Tamil Nadu date to the third century BCE and describe the livelihoods of Tamil Jains. Samaṇar wrote much Tamil literature, including the important Sangam literature, such as the Nālaṭiyār, the Silappatikaram, the Valayapathi and the Seevaka Sinthamaṇi. Three of the five great epics of Tamil literature are attributed to Jains.[2]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 83,359[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

History

Origins

Some scholars believe that Jain philosophy must have entered South India some time in the sixth century BCE. Literary sources and inscription state that Bhadrabahu came over to Shravanabelagola with a 12,000-strong retinue of Jain sages when north India found it hard to negotiate with the 12-year long famine in the reign of Chandragupta Maurya. Even Chandragupta accompanied this constellation of sages. On reaching Shravanabelagola, Bhadrabahu felt his end approaching and decided to stay back along with Chandragupta and he instructed the Jain saints to tour over the Chola- and Pandyan-ruled domains.

According to other scholars, Jainism must have existed in South India well before the visit of Bhadrabhu and Chandragupta. There are plenty of caves as old as fourth century with Jain inscriptions and Jain deities found around Madurai, Tiruchirāppaḷḷi, Kanyakumari and Thanjavur.

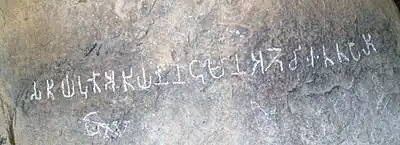

A number of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions have been found in Tamil Nadu that date from the second century BCE. They are regarded as associated with Jain monks and lay devotees.[3][4]

The exact origins of Jainism in Tamil Nadu is unclear. However, Jains flourished in Tamil Nadu at least as early as the Sangam period. Tamil Jain tradition places their origins are much earlier. The Ramayana mentions that Rama paid homage to Jaina monks living in South India on his way to Sri Lanka. Some scholars believe that the author of the oldest extant work of literature in Tamil (3rd century BCE), Tolkāppiyam, was a Jain.[5]

Tirukkural by Thiruvalluvar is considered by many to be the work of a Jain by scholars like V. Kalyanasundarnar, Vaiyapuri Pillai,[6] Swaminatha Iyer,[7] and P. S. Sundaram.[8] It emphatically supports strict vegetarianism (or veganism) (Chapter 26) and states that giving up animal sacrifice is worth more than thousand burnt offerings (verse 259).

Silappatikaram, the earliest surviving epic in Tamil literature, was written by a Samaṇa, Ilango Adigal. This epic is a major work in Tamil literature, describing the historical events of its time and also of then-prevailing religions, Jainism, Buddhism and Shaivism. The main characters of this work, Kannagi and Kovalan, who have a divine status among Tamils, Malayalees and Sinhalese were Jains.

According to George L. Hart, who holds the endowed chair in Tamil Studies by University of California, Berkeley, has written that the legend of the Tamil Sangams or "literary assemblies", was based on the Jain sangham at Madurai:

There was a permanent Jaina assembly called a Sangha established about 604 CE in Madurai. It seems likely that this assembly was the model upon which tradition fabricated the Sangam legend.[9]

Jainism became dominant in Tamil Nadu in the fifth and sixth century CE, during a period known as the Kalabhra interregnum.[10]

Decline and survival

Jainism began to decline around the eighth century CE, with many Tamil kings embracing Hindu religions, especially Shaivism. Still, the Chalukya, Pallava and Pandya dynasties embraced Jainism. The Shaivite legend about the impalement of the Jains in Madurai claims that 8000 Jains were impaled after they lost a contest against the Saivites, Thirugnana Sambandhar was invited by the queen of Madurai to check the atrocities against Jains and their influence on the King; however, this legend is not mentioned in any Jain text[11] According to Paul Dundas, the story represents the abandonment of Madurai by Jains for various reasons or the gradual loss of their political influence.[12]

Jainism survived in the region during the period of decline.[13] The Melsithamur matha was established by a monk Shantisager who arrived from Shravanabelgola sometime during the 9-12th century period as attested by the 12th century inscriptions. A Jain center associated by Acharya Akalanka in the eighth century survives at Thiruparuttikundram near Kanchi. The Tamil Jain texts of this period include 13th-century (orlater) Aruṅkalacceppu, 14th cent. Mērumantarapūrāṇam and the 15th-century Śrīpurāṇam.

Revival

When India became independent in 1947, Madras Presidency became Madras State, comprising present day Tamil Nadu, coastal Andhra Pradesh, South Canara district Karnataka, and parts of Kerala. The state was subsequently split up along linguistic lines. In 1969, Madras State was renamed Tamil Nadu, meaning Tamil country.[14][15]

Acharya Nirmal Sagar was the first Digambar Jain monk to reenter Tamilnadu in 1975 after a gap of several centuries.[16] After him some of the Jain nuns have visited Tamilnadu resulting in a renaissance of Jainism among the Tamil Jains. Many abandoned and crumbling temples have been renovated as a result of renewed interaction between Tamil Jains and the Jains from the rest of India. Financial grants have been provided by Bharatiya Digambar Jain Tirth Samrakshini Mahasabha and the Dharmasthala institutions.[17][18] Local Jain scholars and activists have started "Ahimsa walks" to bring attention to the Tamil Jain heritage.[19][20]

Archaeological evidences

Archaeological remains in Tamilnadu are discovered time to time that attest to popularity of Jainism in Tamilnadu. Most of the rock inscriptions are related to the Jain ascetics who used to commonly reside in hill caves.[21] The ruins of Anandamangalam vestiges were discovered in Anandamangalam, a small hamlet near Orathi village in Kancheepuram district of Tamil Nadu. The ruins had the rock-cut sculptures of yakshini (tutelary deity) Ambika and tirthankara Neminatha and Parshvanatha.[22]

Population

The total number of Jains in Tamil Nadu as per 2011 Indian census is 83,359,[1] which forms 0.12% of the total population of Tamil Nadu (72,138,958). This include the Jains who have migrated from North India (mainly Rajasthan and Gujarat).[23] The population of Tamil Jains is estimated to be 25,000-35,000.[24]

| Parameter | Population | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 83,359 | 43,114 | 40,245 |

| Literates Population | 68,587 | 36,752 | 31,835 |

| Workers Population | 26,943 | 23,839 | 3,104 |

| Cultivators Population | 2,216 | 1,675 | 541 |

| Agricultural Workers Population | 768 | 325 | 443 |

| HH Industry Workers Population | 574 | 441 | 133 |

| Other Workers Population | 23,385 | 21,398 | 1,987 |

| Non-Workers Population | 56,416 | 19,275 | 37,141 |

The Tamil Jains are ancient natives of Tamil Nadu[25] and belong to the Digambara sect.[26] They generally use the title Nainar. A few in Thanjavur District, use Mudaliar and Chettiar as titles.[27] The former North Arcot and South Arcot (now Tiruvannamalai, Vellore, Cuddalore and Villupuram Districts) districts have a large number of Jain temples, as well as a significant population of Tamil Jains.[28]

At present, most of the Tamil Jains are from the Vellalar social group.[29] Also, the Saiva Velaalar sect are originally believed to have been Jainas before they embraced Hinduism.[30] The Tamil Jains refer to the Saiva Velaalar as nīr-pūci-nayinārs or nīr-pūci-vellalars meaning the vellalars who left Jainism by smearing the sacred ash or (tiru)-nīru.[31] While some of the Jains assign this conversion to the period of the Bhakti movement in Tamil nadu others link it to a conflict with a ruler of the Vijayanagar empire in the 15th century. The villages and areas settled by the Saiva Velaalar even now have a small number of Jaina families and inscriptional evidence indicate that these were earlier Jaina settlements as is evident by the existence of old Jaina temples.[32]

The title Nainar has been used since antiquity for Jain monks. In Cilappatikaram a Jain temple is mentioned as Nayinar Koil and the Kalugumalai inscription refers to Jaina munis as Nayinar.[33] It is akin to the term Sahu or Sadhu in North Indian Jain inscriptions.

Religious head

Bhattaraka Laxmisena

Swasthi Shree Bhattaraka Laxmisena Swamiji of Jina Kanchi Jain Mutt or madam at Mel-Sithamoor (near Tindivanam, Villupuram District) is one of the religious heads of the community. He performs the Upadesam ceremony for Jain children. In the past, this mutt had been the centre for religious study, guiding and helping the economic activities of its members, organising religious discourses, maintenance of temples and such activities. The mutt was able to achieve such multifarious operations with the help and contributions of its members. At present the mutt is also maintaining a gousala (for cows and others).

The present finance position of the mutt is inadequate for even day-to-day maintenance. Planting of coconut and mango trees has been started to increase the revenue of the fund for the purpose of day-to-day maintenance of the mutt. The car ('ther') in the mutt requires replacement of wooden wheels.

Swasthi Shree Dhavalakeerthi Bhattaraka Swamiji

In addition to the above, a new mutt named Arahanthgiri Jain Math located at Thirumalai near Polur, Tiruvannamalai district, has been functioning from 8 February 1998 with the name Dhavalakeerthi Swamigal. Now in the mutt around 2300 students are studying from primary to higher secondary school including Jain philosophy with free boarding and lodging. Maintenance of the above is done through contributions from donors.[34]

Lifestyle

The traditional occupation of the majority of the Tamil Jain families has been landowners of agricultural land. Now many are teachers. A considerable number of them are settled in urban areas, they are employed in public and private sectors. A small population has settled overseas (US, Canada, UK, Australia and other places).

Cuisine

Tamil Jains are ardent vegetarians. With the turn of the 20th century, they were a self-sustained rural-based farming community. They were landowners and used contract labourers for their agricultural activities. Their household included large tracts of land, cattle, and milch cows. They had kitchen gardens growing vegetables for their daily need. Dairy food such as milk, curd, butter and ghee were cooked in house. Daily food was very simple consisting of a brunch with rice, cooked lentils (paruppu), ghee, vegetable sambar, curd, sun-dried pickles of mango, lemon or citron, and deep-fried sun-dried 'crispies' (vadavam) made from rice pie. Evening snacks of deep-fried lentil preparations and before sunset dinner consisting either idli, dosa or rice with buttermilk and lentil chutney (thogaiyal). While seniors, people undergoing religious fast and ardent followers of religious principles avoided garlic, onions and tubers in their daily food, these were occasionally used by others in the household.

Identity

Tamil Jains are well assimilated in Tamil society, without any outward differentiation. Their physical features are similar to Tamils. Apart from certain religious adherences, practices and vegetarianism, their culture is similar to the rest of Tamil Nadu. However, they name their children by the names of Tirthankaras and characters from Jaina literature. It is also notable that the men of the Tamil Jain community also wear the sacred thread.

Lifetime ceremony

Ezhankaapu - on the seventh day of its birth, a new born baby is adorned with bracelets.

Kaathu Kutthal - ear piercing and adorning child with earrings. This ceremony is mostly performed in either Aarpakkam temple or Thirunarangkondai i.e.Thirunarungkundram. (Appandai Nathar is the deity).

Other Ceremonies

Upadesam - the formal induction into religious practices and adherences is called Upadesam. This is done to both boys and girls, at around the age of 15. After Upadesam, one is supposed to follow religious practices with vigor and seriousness.

Marriage - outwardly, Jain marriages resemble Hindu marriages. However, the mantras chanted are Jain. There is no Brahmin priest; instead there is a Samaṇar called a Koyil Vaadhiyar or temple priest, who conducts the ceremonies.

Pilgrimage - most Jains go on pilgrimage to tirthas and major Jain temples in North India - Sammed Shikharji, Pavapuri, Champapuri and Urjayanta Giri - as well as places in South India such as Shravanabelagola, Humcha or Hombuja Humbaj, Simmanagadde in Karnataka and Ponnur Malai in Tamil Nadu.

There are private amateur tour operators as well who take pilgrims to newly identified ancient Tamil Jain sites in western Tamil Nadu (kongunadu) and northern Kerala (vayanadu).

Funeral rites - the dead are placed on a pyre and incinerated. Ashes are then disbursed in water courses and ceremonies are performed on 10th or 16th day. Annual remembrance ceremonies similar to Hindu practice are not performed. But no festivities or functions are followed that year on the paternal side.

Festivals

- Akshaya Tritiya commemorates the first Tirthankara, Rishabha, partaking food after many long years of penance.

- Jinaratri commemorates Rishabha's moksha.

- Mahavir Janma Kalyanak celebrates Tirthankara Mahavira's birth.

- Diwali commemorates Mahavira's moksha.

- Vasant Panchami honors the Jain Agamas

- Upaakarma commemorates the Chakravartin Bharata, son of Rishabha, acknowledging the true scholars by awarding them the Upanayana.

- Karthikai Deepam at the onset of the month of Kartika

- Puthandu and Thai Pongal are the other common festivals celebrated along with other Tamils.

Religious practices

Full moon days, Chaturdasi (14th day of the fortnight), Ashtami (8th day of the fortnight) are days chosen for fasting and religious observations. Women take food only after reciting the name of a tirthankara five times. People undertake such practices as a vow for certain period of time - sometimes even for years. On completion, Udhyapana festivals (special prayer services) are performed, religious books and memorabilia are distributed. People who take certain vows eat only after sunrise and before sunset.

List of Tamil Jains

- Prof. A. Cakravarti Nayanar, scholar and author, including "Jaina Literature in Tamil", 1941,[35]

- Jeevabandhu T.S Sripal[36]

- S. Sripal, Director General of Police in Tamil Nadu.

- Prof. J. Srichandran, Founder, Varthamanan Padippagam

- Air Marshal Simhakutty Varthaman.[37]

- Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman.[37]

Temple locations

Cave temples

Puja temples

- is done in the following old (built several centuries ago) and new (built in the last 100 years) Tamil Digambara Jain temples

(in alphabetical order):

- Aadhinath Jain Temple, Cuddalore (old)

- Anumanthakudi, Sivagangai dt.(new)

- Adambakkam, Adi Nath Digambar Jain Temple Chennai (New)

- Agalur, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Agarakorakottai, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Alagramam Jain Temple, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Arahanthgiri Jain Math, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Arani (S.V.Nagaram), Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Arani (Pudukamur), Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Arani (Saidapet), Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Arani (Palayam), Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Arani (Kosapalayam) Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Arani (sevoor) Thiruvannamalai

- Arungulam Kanchipuram Dt. (Old)

- Arpaakkam, Kanchipuram Dt. (Old)

- Arugavur, Solai, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Avadi, Chennai Dt.(New)

- Ayalavadi, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Chitharal Jain Temple,(Old) : ninth century temple

- Chitharal malaikovil,(Old) : before 425 CE

- Cheyyar, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Deepangudi, Nagapattinam Dt. (Old)

- Easaakolathur, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Elangadu, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Eyyil, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Erumbur, Thiruvannamalai Dt.(Old)

- George Town, Chennai Dt. (New)

- Gingee, Viluppuram Dt. (Old)

- Ilayangudi, Sivagangai Dt. (New)

- Kannalam, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Kallapuliyur, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Kallakullathur, Villupuram Dt. {old}

- Karanthai, Kanchipuram Dt. (Old)

- Karanthai Jain Temple, Thanjavur Dt. (Old)

- Kalugumalai Jain Beds Dt. (Old)

- Kanchiyur Jain cave and stone beds Dt. (Old)

- Kattumalaiyanur, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Keezh Villivanam, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Keezh Edayalam, Villupuram Dt.

- Kilsathamangalam, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Koliyanur, Villupuram Dt.(Old)

- Kolathur, Chennai Dt. (New)

- Kovilampoondi, Thiruvannamalai Dt (Old)

- Kumbakonam, Thanjavur Dt. (Old)

- Mannargudi Mallinatha Swamy Jain Temple, Nagapattinam Dt. (Old)

- Melapandal, Vellore Dt. (New)

- Melmalaiyanur, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Mel Sithamur Jain Math, Villupuram Dt.

- Mettu Street, Kanchipuram (New)

- Mudalur, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Nallavanpalayam, Thiruvannamalai Dt.(New)

- Nallur, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Nanganallur, Chennai Dt. (New)

- Naval, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Nedimolliyanur Villupuram Dt. {old}

- Nelliyankulam, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Othalavaadi, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Parshwa Padmavathi Jain Temple, Sundampatti, Orappam Krishnagiri Dt. (Old)

- Pammal, Chennai (New)

- Peranamallur, Thiruvannamalai Dt (Old)

- Perani, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Peravoor, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Periyakozhappalur, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Perumandur, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Perumbogai, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Poondi Arugar Temple, (Old)

- Ponnur Malai, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Puzhal, Chennai Dt. (New)

- Renderipet, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- R.Kunnathur, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Shri Vasupujya Temple, Sathuvachari, Vellore Dt. (old)

- Sathuvachari, Vellore Dt. (New)

- Sevur, Vellore Dt. (Old)

- Sitharaal, Nagercoil Dt. (Old)

- Sittanavasal, Pudukottai Dt. (Old)

- Sitthamur, Villupuram Dt. (Oldest Jain temple and Jain math)

- Somaasipadi, Thiruvannamalai (New)

- Thellar, thiruvannamalaiDt.

- Thirunarunkundram, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Thiruparuthikundram temple, Kanchipuram Dt. (Old)

- Thirupanamoor, Thiruvannamalai Dt. near Kanchipuram

- Thachambadi, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Thatchur, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Thayanur, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Thennathur, Thiruvannamalai Dt.(old)

- Thirakoil, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Thirupparankunram, Madurai Dt.(Sangam literature Paripadal 19 step 51)

- Thiruvannamalai, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (New)

- Thondur, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Tindivanam, Villupuram Dt (New)

- Tirumalai,Polur Dt.(Old)

- Trilokyanatha Temple, Kanchipuram Dt (Old)

- Valathi / Valathy, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Vandavasi, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Valapandal Vellore Dt. (Old)

- Veedur, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Veeranamur, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Vellimedupettai, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Vempoondi, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Venbakkam, Kanchipuram Dt. (Old)

- Vilangadupakkam, Chennai Dt. (Old)

- Vizhukkam, Villupuram Dt. (Old)

- Vijayamangalam, Erode Dt. (Old)

- Virudur, Thiruvannamalai Dt. (Old)

- Nasiyan Jain Temple,Prithvi Raj Road,ooty,dedicated to Rishabhdevji.[38]

- Sri 1008 Vaupujya Swamy Swethambar Jain Temple, Ooty[39]

Photo gallery

Thirakoil Hill and the Digambara Jain Temple.

Thirakoil Hill and the Digambara Jain Temple.

Samanar Padukkai in Sittanavasal

Samanar Padukkai in Sittanavasal Samanar Malai near Madurai, where the eighth century Jain caves still exist.

Samanar Malai near Madurai, where the eighth century Jain caves still exist. Mulnayak Shri Parshvanath within the main temple at the Mel Sithamur Jain Math.

Mulnayak Shri Parshvanath within the main temple at the Mel Sithamur Jain Math. During a festival morning at the Mel Sithamur Jain Math.

During a festival morning at the Mel Sithamur Jain Math.

Members of the Tamil Jain community at the Gingee Jain temple, Gingee, Villupuram district, Tamil Nadu, India.

Members of the Tamil Jain community at the Gingee Jain temple, Gingee, Villupuram district, Tamil Nadu, India.

Tamil Jain Books

"Jeevaka Chinthamani", "Sripurana" by J Srichandran.[40]

Notes

Citations

- "Directorate of Census Operations – Tamil Nadu". census2001.tn.nic.in. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Jaina Literature in Tamil, Prof. A. Chakravarti

- Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the sixth Century A.D., Iravatham Mahadeva, Harvard University Press, 2003

- http://jainsamaj.org/rpg_site/literature2.php?id=595&cat=42 RECENT DISCOVERIES OF JAINA CAVE INSCRIPTIONS IN TAMILNADU, by Iravatham Mahadevan

- Singh, Narendra (2001). Encyclopaedia of Jainism. Anmol Publications. p. 3144. ISBN 978-81-261-0691-2.

- Tirukkural, Vol. 1, S.M. Diaz, Ramanatha Adigalar Foundation, 2000,

- Tiruvalluvar and his Tirukkural, Bharatiya Jnanapith, 1987

- The Kural, P. S. Sundaram, Penguin Classics, 1987

- "The Milieu of the Ancient Tamil Poems, Prof. George Hart". 9 July 1997. Archived from the original on 9 July 1997. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- John E. Cort 1998, p. 187.

- Ashim Kumar Roy (1984). "9. History of the Digambaras". A history of the Jainas. Gitanjali. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- Paul Dundas (2002). Jains. Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-415-26606-2. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Jainism in the Tamil-Speaking Region, Christoph Emmrich, Brill Encyclopedia of Jainism, 2019

- "Jainism in Tamilnadu".

- Tamil Jain? by Mahima Jain, The Hindu, 28 December 2013.

- Acharya Nirmal Sagarji Maharaj, 1975, 03.08.2015

- Taminadu Digambar Jain Tirtha Kshetra Sandarshana, 2001

- Anointment rituals of Lord Bahubali performed by Jains from Tamil Nadu, Times of India, 12 Mar 2019

- This Chennai group explores the hidden, not-so-famous Jain temples of Tamil Nadu, Anjana Shekar, 30 August 2018

- The Jain connection in Tamil Nadu, Tamanna Shah, Express News Service, 22 May 2018

- Deciphering Tamil-Brahmi and Vattezhuthu scripts, Nahla Nainar, Hindu, FEBRUARY 3, 2017

- Bhaskaran, S. Theodore (27 November 2015), The Jain ruins of Anandamangalam in Tamil Nadu, though small in size, have sufficient details to merit close attention, Frontline

- Tamil Jain?, Mahima Jain, The Hindu, DECEMBER 28, 2013

- The Tamil Jains: A minority within a minority, Mahima A. Jain, South Asia @ London School of Economics, 11 December 2015

- Genetic admixture studies on four in situ evolved, two migrant and twenty-one ethnic populations of Tamil Nadu, south India, G. SUHASINI et al, Journal of Genetics, Vol. 90, No. 2, August 2011., p. 191-202

- [Volume 40 of People of India, Kumar Suresh Singh, Volume 3 of People of India: Tamil Nadu, Anthropological Survey of India, Affiliated East-West Press for Anthropological Survey of India, 1997, p. 1437]

- Reading History with the Tamil Jainas, A Study on Identity, Memory and Marginalisation, R. Umamaheshwari, Springer, Indian Institute of Advanced Study, p.4, 111

- Castes and Tribes of Southern India, Volume II of VII By Edgar Thurston, Library of Alexandria,

- R. Umamaheshwari (2018). Reading History with the Tamil Jainas. A Study on Identity, Memory and Marginalisation. Volume 22 of Sophia Studies in Cross-cultural Philosophy of Traditions and Cultures. Springer. p. 250.

- Andhra University (1972). Religion and Politics in Medieval South India. Papers of a Seminar Held by the Institute of Asian Studies and Andhra University. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 15.

- R. Umamaheshwari (2018). Reading History with the Tamil Jainas. A Study on Identity, Memory and Marginalisation. Volume 22 of Sophia Studies in Cross-cultural Philosophy of Traditions and Cultures. Springer. p. 222.

All of those who feared for their lives converted to Saivism (and not any other religious sect) adorning the sacred ash, 'throwing away their sacred threads', they assumed the identity of Saiva (nir-puci) vellalars or nir-puci-nayinars (the Jainas who smeared sacred ash).

- R. Umamaheshwari (2018). Reading History with the Tamil Jainas. A Study on Identity, Memory and Marginalisation. Volume 22 of Sophia Studies in Cross-cultural Philosophy of Traditions and Cultures. Springer. p. 223.

- Identities in conflict: Jainism in early tamilakam, Maheshwari, R. Uma, Jawaharlal Nehru University PhD Dissertation, 2007, Chapter II The Tamil Jaina Community: Questions of Identity, p. 85

- "Swasthy Shree Dhavalakeerthi Swamiji". Akalanka-educational-trust.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- The Ins and Outs of the Jains in Tamil Literary Histories, Christoph Emmrich, J Indian Philos (2011) 39:599–646

- R. Umamaheshwari, ‘Retrieving’, Seeking, the Tamil Jaina Self: the Politics of Memory, Identity and Tamil Language, Reading History with the Tamil Jainas, 26 January 2018, pp 205-298

- Tamil Nadu village prays for safe return of pilot Abhinandan

- "Ooty: Jain Temple, Ooty". Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Gallery - Category: Ooty - Image: Sri 1008 Vaupujya Swamy Swethambar Jain Temple, Ooty". Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- For this 87-year-old, bringing epics to lay readers is a passion by MT Saju. The Times of India, 8 January 2015.

References

- John E. Cort, ed. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-3785-X

External links

- French Institute of Pondicherry Project on Jaina Temples of Tamil Nadu - a combined DVD/website project presently being prepared for publication that will include information on over 400 Jain sites around Tamil Nadu.

- Tamil Jains

- Jain vestiges

- Unexploited vestiges of Jainism[Usurped!]

- 1008 Jainism Books Launched in Single Pen Drive by Acharya Suvidhisagarji Maharaj in Chennai, Tamilandu

- Jainism in Tamilnadu Blog

- Jainism Resource Center Archived 25 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine