Sagrestia Nuova (New Sacristy)

Sagrestia Nuova, also known as the New Sacristy in English, is a mausoleum that stands as a testament to the grandeur and artistic vision of the Medici family. Constructed in 1520, the mausoleum was built by the Italian artist Michelangelo. Situated adjacent to the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence, Italy, the Sagrestia Nuova forms an integral part of the museum complex known as the Medici Chapels.[1]

| New Sacristy | |

|---|---|

Sagrestia Nuova | |

.jpg.webp) Sagrestia Nuova at the Basilica di San Lorenzo | |

| Location | |

| Location | Piazza Madonna degli Aldobrandini, Florence, Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 43°46′30″N 11°15′13″E |

| Architecture | |

| Date established | 1520 |

| Completed | 1533 |

History

The Medici family, one of the most influential and powerful families during the Italian Renaissance, played a pivotal role in the political, economic, and cultural landscape of Florence. With their immense wealth and patronage of the arts, the Medicis became patrons to many great artists, including Michelangelo.

Commissioned by Pope Clement VII, a member of the Medici family, Michelangelo embarked on the ambitious project of designing and constructing a mausoleum that would serve as the final resting place for members of the Medici dynasty. The Sagrestia Nuova was specifically intended to house the remains of two notable Medici figures: Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours and Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino.

The Sagrestia Nuova is a testament to Michelangelo's genius and artistic prowess. The mausoleum showcases his mastery in both architecture and sculpture. Michelangelo carefully designed the space, taking into consideration the harmony between the structure and the sculptures that would adorn it. The mausoleum's architecture reflects Michelangelo's skillful understanding of balance, proportion, and the manipulation of light.

As visitors enter the Medici Chapel, they are greeted by a sense of grandeur and solemnity. The space is divided into two rooms: the Cappella dei Principi (Chapel of the Princes) and the Sagrestia Nuova. The Cappella dei Principi, the larger of the two rooms, features a stunning dome adorned with intricate frescoes and an imposing coffered ceiling. The walls are adorned with elegant marble panels, creating an ambiance of opulence and magnificence.

The Sagrestia Nuova is a smaller, more intimate space. Its main focal point is the grand Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours and the Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici Duke of Urbino, which are sculpted with exquisite attention to detail. Michelangelo's sculptures beautifully capture the essence of the Medici family, depicting them in a solemn and dignified manner. These sculptures, known as the Medici Tombs, are considered some of Michelangelo's finest works and a testament to his ability to bring marble to life.

The Sagrestia Nuova serves as a significant historical and cultural landmark, offering visitors a glimpse into the rich legacy of the Medici family. Beyond its architectural and artistic value, it also serves as a reminder of the Medici's contributions to the arts and their enduring influence on Florentine society.

Today, the Sagrestia Nuova is open to the public as part of the Medici Chapels Museum complex. Visitors can appreciate Michelangelo's genius up close, marvel at the intricate details of the sculptures, and immerse themselves in the historical and artistic significance of the Medici family.

Premises

The death of the two descendants of the Medici family, Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours in 1516 and Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino in 1519, had deeply embittered Pope Leo X, respectively brother and uncle of the two, who wanted to ensure that they obtained a princely burial. It was also suggested by their cousin Giulio de' Medici, cardinal and later Pope Clement VII in 1523, commissioning Michelangelo's project for the façade for Basilica di San Lorenzo, engaging the artist in a new project for the basilica. The church had been the burial place of the Medici family for a century, but at the time there were no spaces available in which to create a new monumental complex: the historic family chapel, the Old Sacristy, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi, and Donatello, was a set of sober and measured balance, in which no other decorations could be added without compromising the whole. The crypt, where some family members are located, was not up to the clients' wishes for splendor and celebration. Not even for Lorenzo de' Medici and his brother Giuliano de' Medici had a worthy burial been prepared. There was a need to create a new environment to place the remains of the two "dukes" (or "captains") and the two "magnificents."[2]

Design

Michelangelo was chosen for the construction, recovering from the impasse on the facade project, whose contract was definitively terminated in March 1520. The exact contracting document is not known, but from other documents and letters it is clear, that in March work on a new chapel had been started.[2]

An independent room was designed, symmetrical and similar in proportion to Brunelleschi's sacristy, at the crossroads between the transept and the chevet on the north side. The plan chosen was completely like the model: a square base with a scarsella on the west side in a ratio of 1/3, and two service rooms on either side of the scarsella, all covered by a dome with lantern.

During the design phase, Michelangelo thought of various solutions, before choosing the version implemented. The question was how to arrange the four sepulchers in relation to the available space, with the altar and the entrance. The first idea was tombs placed at the corners leaning against the walls (March 1520), but on October 23, 1520, Michelangelo presented Cardinal Giulio with a project with a aedicula in the center containing the tombs. A drawing was provided on December 21, 1520.[2] The artist therefore abandoned the scheme of the tombs in the centre, opting for their arrangement against the walls and studying variants with single or double burials, until arriving at a defined project with single tombs for the dukes in the side walls and double ones for the magnificent on the wall opposite the altar. Only those of the dukes were finally completed.[2] In 1521 Pope Leo died and work was interrupted.[2]

Second stage

With the election to the throne of Clement VII, in 1523, in December of that year the artist returned to the works of Basilica di San Lorenzo. It was thought to house the tombs of Pope Leo and, at the time, of Clement VII in the Sacristy, but the idea was soon abandoned in favor of the choir of San Lorenzo. In the end, however, both were buried in Basilica di Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome.[2]

In the spring of 1524, Michelangelo was working on the clay models for the sculptures and in the autumn the marbles arrived from Carrara. Between 1525 and 1527 at least four statues were completed (including the Night (Michelangelo) and the 'Aurora (Michelangelo)) and four others were already defined with the models.[2]

In 1526, the first tomb was walled up, the Tomb of Lorenzo Duke of Urbino. On June 17, the artist sent a letter to Rome in which he wrote: "I work as hard as I can, and in fifteen days I'll get the other captain started, then I'll be left, of matters of importance, only and four figures. The four figures on the cassoni, the four figures on the ground, which are Rivers, and two captains and Our Lady going to the tomb at the head, are the figures I would like to make with my own hand: and of these there is six begin, and the courage is enough for me to do them in the right time and partly do the others that don't matter so much." It is therefore understandable that in addition to the actually existing sculptures, four river allegories were also envisaged (the rivers of Hades, or perhaps the rivers under Medici rule) lying at the foot of the tombs, of which only the model of the River God at Casa Buonarroti.[2]

Interrupting and resuming jobs

With the heavy blow received by Pope Clement during the sack of Rome (1527), the city of Florence rebelled against the Medici rule, driving out the little loved duke Alessandro de' Medici (duke of Florence). Michelangelo, despite being linked to the Medici by working relationships since his youth, blatantly sided with the republican faction, actively participating, as person in charge of the fortifications, in the defense measures against the siege of the 1529-1530. Defeated the Florentines, Michelangelo fled the city, but was declared a rebel and presented himself spontaneously to avoid more serious punitive measures. Clement VII's pardon was not long in coming, provided that the artist immediately resumed work in San Lorenzo where, in addition to the Sacristy, the project for a monumental Medici Laurentian library had been added five years earlier. It is clear how the pope was moved by the awareness of not being able to renounce the only artist capable of giving shape to the dreams of glory of his dynasty, despite his ungrateful nature and ready to betray.[3]

In April 1531, work resumed on the Sacristy and by the summer two more statues had to be completed and a third started. It is also known that the Portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici duke of Urbino was executed between 1531 and 1534, while Portrait of Giuliano de' Medici duke of Nemours, that of Giuliano in 1533 was given to Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli for finishing. In that same period the artist was preparing two allegorical statues, the Heaven and the Earth, which should have been sculpted by Niccolò Tribolo and placed in the niches on the sides of Giuliano's tomb, however remained empty: two more evidently had to be planned for the tomb of Lorenzo.[2]

In the meantime, between 1532 and 1533, on a project by Michelangelo who had already sent sketches from Rome in 1526, Italian painter and architect Giovanni da Udine worked on stuccoes and decorations in the dome, of which no trace remains after the eighteenth-century interventions promoted by the Elettrice Palatina Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici who covered the dome with only stucco as it appears to us today.

While the Florentine works by now proceeded more and more slowly because in those same years Michelangelo was also working, in addition to the library, on the tomb of Julius II, for which he was preparing the Prisoners. Michelangelo, not happy with the city's political climate, took the opportunity to take new assignments in Rome and left Florence, in 1534, never setting foot there again.[3]

In 1559, on the initiative of Cosimo I de' Medici, the chapel was arranged according to the project by Giorgio Vasari. Although an entire wall with the tomb of the "Magnificent" was missing and the river deities, statues, stuccos and frescoes required by the contract had yet to be created, the Sacristy was considered completed.[2]

Architecture

Born in the midst of such tumultuous events, the New Sacristy is a very innovative work. Starting from the same plan of the Old Sacristy, Michelangelo divided the space into more complex forms, treating the walls with floors at different levels in complete freedom. On these he cut out classical elements such as arches, pillars, balustrades and frames, now in marble and now in pietra serena, however arranged in completely new shapes and schemes.

The walls are based on a tripartition by stone pillars in giant order. At the corners there are eight doors of the same design, now true and now false: the frames are surmounted by an aedicule resting on a shelf supported by volutes, which coincides with the architrave; they are crowned by circular tympanums resting on small pillars which are close together towards the inside. In each aedicule a double panel opens, the upper line of which touches the tympanum, creating a lively interplay of lines. Inside, instead of the statues or bronze reliefs perhaps foreseen in the original project, there are festoons in relief and a patera.

At the center of these side elements that recur throughout the walls are the purse, on the side of the altar, the unfinished tomb of the "Magnificent" and the two tombs of the "Dukes" on the side walls. The latter, above the simple mirrors profiled in the lower half, present an internal tripartition in the median band, in which we see the rectangular niche with the statue of the deceased in the center and on the sides, divided by paired marble pillars, two niches with an arched tympanum on shelves resting on the frame, which resume, simplifying it, the design of the niches above the portals. The tombs therefore fit into the walls by interacting with the architecture, rather than simply leaning against it. Further up, the lower entablature, present only on the sides of the tombs, shows festoons in relief above the tympanums, balustrades on which the cornice can be pronounced over the pillars, and in the center a flat band enlivened by a central volute, citing the Roman arches. Above, the entablature in sandstone runs along the entire perimeter of the space, on which runs a smooth white frieze and a second molded stone frame. The central arch of the wall, one third of the surface wide, and small pillars in pietra serena that still divide the space into three sections are set on it. Above the arch some recessed compartments create a refined play of light; on the sides of this band, aligned with the portals, are the stone windows, with a developed triangular tympanum, creating the effect of tapering and therefore of upward acceleration.

The sculptures

Embedded in the two side walls are the monumental tombs dedicated Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici duke of Nemours and Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici duke of Urbino. Initially up to five sculptures per tomb were to be carved, but then they were reduced to three. For the funerary monuments on both sides of the chapel, Michelangelo created the Allegories of Time, which symbolize the triumph of the Medici family over the passing of time. The four Allegories are placed above the sepulchers, at the feet of the dukes. The elliptical line on which they rest is a Michelangelo invention that anticipates the curves of the Baroque, as in the staircase of the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. For the tomb of Giuliano de' Medici, he chose the Day and the Night, for that of Lorenzo the Twilight (Michelangelo) and the 'Aurora (Michelangelo). Even the four Rivers, never built, were supposed to recall the permanent and unstoppable flow of time.[2]

All the Allegories are characterized by stretching and twisting and appear "unfinished" in some parts. Particularly beautiful are the emblematic position of the Day, turned from the back which shows only the mysterious expression of the eyes in a barely sketched face, or the body of the Night which perfectly represents abandonment during sleep. In the Renaissance, especially in environments influenced by neoplatonism Florentine (Marsilio Ficino), the Night rediscovers its attributes of Primordial Mother and is associated with the figure of Leda. The position of the goddess, with her head bowed, expresses the kinship of the Night with the melancholic temperament. The owl and the poppies are symbols of Death and Sleep, the twin sons of Night. According to the doctrines of Orphism and Pythagoreanism, Leda and the Night are the personification of a double theory of death, according to which joy and pain coincide.[4] Aurora then seems caught in the act of waking up and realizing, with pain, that Lorenzo's eyes are closed forever. The female figures, as also happens in the frescoes of the vaults of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, have masculine features, such as broad shoulders or muscular hips: the male body in movement is in fact the recurring subject of all Michelangelo's production, even when it comes to portraying women.

All four statues allegorical are Neoplatonic in the Plotinian sense, in the sense of the unfinished. The portraits of Lorenzo and Giuliano that dominate the tombs, on the other hand, are ideal portraits, Neoplatonic in their perfect execution.

As for the portraits of the dukes, Michelangelo sculpted them seated in two niches above their respective tombs, facing each other, both dressed as Roman leaders. These sculptures, with attention to the smallest details, are idealized and do not reproduce real features, but nonetheless have a strong psychological character (Giuliano sitting in a proud posture with the baton of command is more haughtier and decisive, while Lorenzo, in a thoughtful pose, is more melancholier and meditative). A popular tradition tells that someone criticized the lack of resemblance of the portrait to the true features of Giuliano, Michelangelo, aware that his work would be handed down over time, replied that in ten centuries no one would be able to notice. Giuliano personifies active life, one of the two roads that lead to God. His scepter alludes to royal power, characteristic of those born under the sign of Jupiter. The coins are a symbol of magnanimity and indicate that the active man loves to "expend" himself in action. Lorenzo, known by the name "pensive", represents the contemplative attitude. The shadowed face recalls the facies nigra of Saturn (divinity), protector of melancholics. The forefinger on the mouth traces the saturnine motif of silence. The reclining arm is an iconographic tope of the melancholy mood. The closed casket resting on a leg is an allusion to parsimony, a typical quality of Saturnian temperaments.[4]

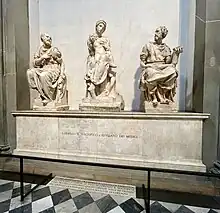

Lorenzo the Magnificent and Giuliano de' Medici

The sepulcher with the mortal remains of Lorenzo the Magnificent (died in 1492) and his brother Giuliano (killed during the Pazzi conspiracy in 1478) is surmounted by three sculptures. The one in the middle is Michelangelo's statue of Madonna with Child, completed in 1521. Next to the Madonna are the two patron saints of the Medici family, the Saint Cosmas and Saint Damiano: on the right Cosma, executed by Florentine sculptor Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli in 1537, and on the left Saint Damiano, by sculptor and architect Raffaello da Montelupo in 1531, who began work at an early age in Florence with Michelangelo, at the Sagrestia Nuova. Saint Cosmas is also attributed to Montelupo, together with Montorsoli, another assistant to Michelangelo, after a model by the master.[5][6]

The three statues were then placed by Giorgio Vasari on a simple marble chest in which Lorenzo the Magnificent and his brother Giuliano de' Medici are buried, for whom there was never the time to build a larger monumental burial.[5]

Graffiti

On the walls of the scarsella is a series of graffitied figures and architectural motifs, referring to Michelangelo's assistants. A trap door in the room to the left of the altar leads to another small barrel-vaulted room, where the artist could retire in solitude. On the walls of this room a large number of graffiti drawings referable to Michelangelo himself were found; the works, carefully cataloged and recently restored, cannot be visited for conservation reasons, but can be enjoyed through an interactive station located behind the altar and in other Michelangelo-style places scattered around the city.[7]

Gallery

_Cappelle_Medicee_Firenze.jpg.webp) Portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino

Portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino_Cappelle_Medicee_Florenz-3.jpg.webp) Dusk (Michelangelo)

Dusk (Michelangelo)_Cappelle_Medicee_Florenz-4.jpg.webp) Aurora (Michelangelo)

Aurora (Michelangelo)_Cappelle_Medicee_Florenz-4.jpg.webp) Portrait of Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours

Portrait of Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours Night (Michelangelo)

Night (Michelangelo) Day (Michelangelo)

Day (Michelangelo)

River god

River god

Other sculptures related to the New Sacristy

- River God, Academy of Drawing Arts, Florence (ca. 1524)

- Crouching Boy Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg (c. 1524)

See Also

References

- "Medici Chapels and Church of San Lorenzo". The Museums of Florence. Florence, Italy. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Baldini, Umberto (1982). The sculpture of Michelangelo. pp. 84, 100–101. ISBN 9780847804474.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Gonzáles, Marta Alvarez (2008). Michelangelo. Mondadori arte. pp. 27, 29. ISBN 978-88-370-6434-1. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- Battistini, Matilde (2005). Symbols and Allegories in Art. pp. 69, 332–333. ISBN 9780892368181. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Wilson, Charles Heath (1881). Life and Works of Michelangelo Buonarroti. p. 263. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "Montórsoli, Giovanni Angelo (in Italian)". Institute of the Italian Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2023-06-07.

- "Michelangelo's secret room". Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

External links

- 500 years of the New Sacristy: Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel by Peter Barenboim (with Heath, Arthur)

_Grobnica_Lorenza_de'_Medici.jpg.webp)