1917 Russian Constituent Assembly election

Elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly were held on 25 November 1917, although some districts had polling on alternate days, around two months after they were originally meant to occur, having been organized as a result of events in the February Revolution. They are generally recognised to be the first free elections in Russian history.[1]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

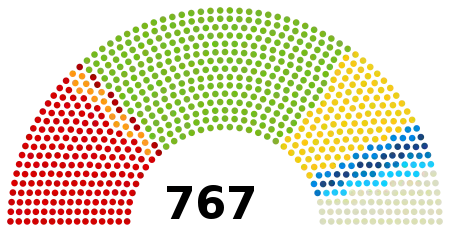

All 767 seats in the Russian Constituent Assembly 384 seats required for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 45,879,381 (64%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Winning party by constituency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Composition of the elected legislature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Various academic studies have given alternative results. However, all clearly indicate that the Bolsheviks were clear winners in the urban centres, and also took around two-thirds of the votes of soldiers on the Western Front. Nevertheless, the Socialist-Revolutionary party topped the polls, winning a plurality of seats (no party won a majority) on the strength of support from the country's rural peasantry, who were for the most part one-issue voters, that issue being land reform.[1]

The elections did not produce a democratically-elected government, as the Bolsheviks subsequently disbanded the Constituent Assembly and proceeded to rule the country as a one-party state with all opposition parties banned.[2][3][4]

Some modern Marxist theoreticians have contested the view that a one-party state was a natural outgrowth of the Bolsheviks' actions.[5] George Novack stressed the initial efforts by the Bolsheviks to form a government with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and bring other parties such as the Mensheviks into political legality.[6] Tony Cliff argued the Bolshevik-Left Socialist Revolutionary coalition government dissolved the Constituent Assembly due to a number of reasons. They cited the outdated voter-rolls which did not acknowledge the split among the Socialist Revolutionary party and the assemblies conflict with the Russian Congress of the Soviets as an alternative democratic structure.[7]

Background

The convocation of a Constituent Assembly had been a long-standing demand of the democratic and popular movements in Tsarist Russia. In the later phase of the February Revolution, Tsar Nicolas II abdicated on March 2, 1917. The Russian Provisional Government was formed and pledged to carry through with holding elections for a Constituent Assembly. Consensus emerged between all major political parties to go ahead with the election. Nevertheless, the various political parties were divided over many details on the organization of the impending election. The Bolsheviks demanded immediate elections, whilst the Socialist-Revolutionaries wanted to postpone the vote for several months for it not to collide with the harvest season. Right-wing forces also pushed for delay of the election.[8]

On March 19, 1917 a mass rally was held in Petrograd, demanding female suffrage. The march gathered some 40,000 participants. The protest was led by Vera Figner and Poliksena Shishkina-Iavein. It moved from the Petrograd City Duma to the Tauride Palace, and the demonstrators refused to vacate the palace grounds before the Provisional Government and the Soviet committed to female suffrage. On July 20, 1917, the Provisional Government issued a decree awarding voting rights for women aged 20 years and above.[9]

In May the political parties agreed on main principles of the election (proportional representation, universal suffrage and secret ballot). A special electoral commission was set up, composed of multiple lawyers and legal experts. The following month September 17, 1917 was set as the election date. The new Constituent Assembly was supposed to have its first meeting on September 30, 1917.[8]

In July the left-wing parties increased their pressure on the Provisional Government, reaching a nearly insurrectionist situation. In the end, the following month the left consented to a further postponement. On August 9, 1917 a new date for the election was set by the Provisional Government: voting on November 12 and the first session of the Constituent Assembly would be held on November 28, 1917.[8][10]

Between the finalization of candidate lists and the election, the October Revolution broke out.[11] The October Revolution ended the reign of the Provisional Government. A new Soviet government took charge of the country, the Council of People's Commissars. Nevertheless, the new government pledged to go ahead with the election and that its rule remained provisional until its authority would be confirmed by the Constituent Assembly.[8]

Electoral system

Electoral Districts of the 1917 Russian Constituent Assembly election | |

|---|---|

|

Northern/Northwestern |

|

Baltic/White Russian |

|

Central Industrial Region |

|

Central Black Earth Region |

|

Volga |

|

Kama-Ural |

|

Ukraine |

|

South-Black Sea/Southeastern |

|

Caucasus |

|

Turkestan |

|

Siberia |

| Military Districts | |

81 electoral districts (okrugs) were formed by the Provisional Government.[12][13] Electoral districts were generally set up on (pre-revolutionary) governorate or ethnic oblast boundaries.[13][14] Moreover, there were electoral districts for the different army groups and fleets.[13] There were also an electoral district assigned for the workers at the Chinese Eastern Railroad and one electoral district for the soldiers of the Russian Expeditionary Corps in France and the Balkans (with some 20,000 voters).[12][15]

No official electoral census exists. The estimated population of eligible voters at the time (excluding occupied territories) has been estimated at around 85 million; the number of eligible voters in the districts where polling took place has been estimated at around 80 million.[12]

Each party had a separate ballot with a list with names of candidates, there was no general ballot. The voter would either have received copies of different party lists in advance or at the polling station. The voter would select one list, place it in an envelope, seal it and place it in the box. If any name was scratched, the vote would be invalid.[16]

Voting

The voting began on November 12–14, 1917.[17][14] The election was at the time the largest election organized in history.[18] However, only in 39 districts did the election take place as scheduled. In many districts the voting occurred in late November or early December, and in some remote places the vote took place only in early January 1918.[10]

In spite of war and turmoil, some 47 million voters exercised their franchise, with a national voter turnout of around 64% (per Protasov (2004)).[19][12] According to Protasov (2004), the countryside generally had a higher voter turnout than the cities. 220 cities across the country, with a combined population of seven million, had a voter turnout of 58%. In agrarian provinces turnout generally ranged from 62 to 80%. In Tambov province urban areas had a turnout of 50.2% while rural areas had 74.5%.[20] According to Radkey (1989) national voter turnout stood at around 55%.[21]

Competing parties

Socialist-Revolutionaries

The Socialist-Revolutionaries emerged as the most voted party in the election, swaying the broad majority of the peasant vote. The agrarian programmes of the SR and Bolshevik parties were largely similar, but the peasantry were more familiar with the SRs. The Bolsheviks lacked an organizational presence in many rural areas. In areas where the Bolshevik electoral campaign had been active (for example, near to towns or garrisons) the peasant vote was somewhat evenly divided between SRs and Bolsheviks.[22]

Moreover, whilst the SRs enjoyed widespread support among the peasantry, the party lacked a strong organizational structure in rural areas. The party was highly dependent on peasant union, zemstvos, cooperatives and soviets.[23]

On the issue of war and peace, the SR leadership had vowed not to enter into a separate peace with the Central Powers. The SR leadership condemned the peace talks initiated by the Bolsheviks, but to what extent the SR's were prepared to continue the war was unclear at the time. Along with the Mensheviks, the SRs supported the notion of engaging with other European socialist politicians to find a settlement to the ongoing World War.[24]

The filing of nominations for the election took place just as the split in the SR party was taking place. By late October, when the SR party lists were already set, the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries formed a separate party.[11][17] But whilst by the time of the election the Left SRs had constituted a separate party, the split was not completed in local SR party branches until early 1918.[23] The Kazan, Yaroslavl, Kazan and Kronstadt SR organizations went over to the Left SRs en bloc. In Ufa and Pskov the majority in the SR party organization crossed over to the Left SRs. In Petrograd the leftist faction had dominated the SR party branch prior to the October Revolution, but elsewhere the majority in the party organizations remained with the PSR.[23] Notably in some of the locations leftist and rights SR lists were separately presented (Baltic Fleet, Petrograd, Kazan), the leftists prevailed over the rightists, leading D'Agostino (2011) to argue that had separate right/left SRs lists been presented nationwide the peasantry could have opted for the left (considering that there were no major difference between the factions on their agrarian programmes).[24]

A key Bolshevik argument against the legitimacy of the Constituent Assembly once it was elected was the fact that the lists had been finalized before the Left SRs constituted themselves as a separate party, and that if the Left SRs had stood separately the Bolshevik and Left SR would have won the majority vote.[25] This was despite the Left SR's eventual opposition to the closure of the Constituent Assembly by the Bolsheviks.[26] Per Serge's account, 40 of 339 elected SR deputies were leftists and 50 belong to Chernov's centrist faction.[27] Smith points out that though the association with Soviet power strengthened the PLSR popularity in the countryside, the schism did not transform the PLSR overnight into a large and well-organized political party, and during the following months of 1918 the PSR managed to regain control over some of the soviets and local branches it lost to the left.[28]

Bolsheviks

In 1917 the Central Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) had begun to allow mass membership, without consulting with Lenin.[29] On July 1, 1917 the Central Committee sent out an instruction to local party organizations to build a broad democratic unity ahead of the elections, to reach out to Menshevik-Internationalists, left-wing SRs and trade unions.[29] In the wake of the abortive July uprising (organized by the revolutionary Petrograd Bolshevik Committee and the Military Organization), the moderates of the Central Committee again appealed to build a left socialist bloc and invited the Menshevik-Internationalists to attend the upcoming party congress as observers.[29] With the election finally approaching, Lenin took a tough stance towards the Central Committee. He deplored the absence of proletarians from the list of proposed candidates that the Central Committee had adopted, charging the Committee with opening the doors for opportunists. In Lenin's view, only workers would be able to create alliances with the peasantry. Lenin also criticised the list for including many recent arrivals to the party who had not yet been tested in "proletarian work in our Party's spirit." While Lenin believed that some new members of the Bolsheviks, in particular Leon Trotsky (who had fought for the merger of his Mezhraiontsy faction into the Bolshevik Party since his return to Russia and had "proved himself equal to the task and a loyal supporter of the party of the revolutionary proletariat"), were acceptable candidates, placing large numbers of untested new members on the Bolshevik ballot opened the party's doors to careerism.[30]

The Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) campaigned for bread, peace and a government of Soviets.[31] But the party leadership was divided on the issue of the Constituent Assembly. The moderates in the Central Committee held the opinion that the Constituent Assembly should become the supreme body to decide the future path of Russia.[29] Lenin opposed this line. In an article edited after the elections, he stated that the proletariat cannot achieve victory if it does not win the majority of the population to its side. But to limit that winning to polling a majority of votes in an election under the rule of the bourgeoisie, or to make it the condition for it, is crass stupidity, or else sheer deception of the workers. In order to win the majority of the population to its side the proletariat must, in the first place, overthrow the bourgeoisie and seize state power; secondly, it must introduce Soviet power and completely smash the old state apparatus, whereby it immediately undermines the rule, prestige and influence of the bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeois compromisers over the non-proletarian working people. Thirdly, it must entirely destroy the influence of the bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeois compromisers over the majority of the non-proletarian masses by satisfying their economic needs in a revolutionary way at the expense of the exploiters.[30]

The party emerged victorious in the two main cities; Petrograd and Moscow, and emerged the major party in urban Russia overall.[22] It won an absolute majority of votes in the Baltic Fleet, the Northern Front and the Western Front.[22] The call for immediate peace made the Bolsheviks popular in the military, winning around 42% of the votes from the armed forces.[25] Often the election result is portrayed as an indicator for impopularity of the Bolsheviks, but as per Victor Serge the strong showing of the Bolshevik vote in the main cities 18 days after the October Revolution broke out shows that there was a popular mandate from the industrial workers for the Revolution.[27]

Mensheviks

By the time of the election, the Mensheviks had lost most of their influence in the workers' soviets.[27] The election result confirmed the marginalization of the Mensheviks, obtaining a little over a million votes.[24] In a fifth of the constituencies, pro-war Mensheviks and Internationalists ran on competing slates and in Petrograd and Kharkov the defencists had set up their own local organizations.[32] Nearly half of the Menshevik vote came from Georgia.[27]

Kadets

The Kadet party had changed its name to 'People's Freedom Party' by 1917, but the new name was rarely used.[33] Kadets campaigned for national unity, law and order, honour commitments to the allies of Russia and 'honorable peace'.[31] The Kadets condemned Bolsheviks in election campaign.[34] The Kadets had sought to build a broad democratic coalition, setting up a liaison committee for alliances (Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, Andrei Ivanovich Shingarev and M. S. Adzhemov) but this effort failed as the Popular Socialists and cooperative movement rejected electoral pacts with the Kadets.[35]

Whilst the Kadets emerged as the main losers in the election, they did take a sizable share of the votes in the largest cities.[8] However the Kadets were hurt by abstention amongst urban intelligentsia voters.[36] They had also lost a large share of their habitual Jewish intelligentsia vote to Jewish national coalition lists.[36]

Popular Socialists

The congress of the Popular Socialists, held on September 26, 1917, rejected the notion of an electoral alliance with the Kadets.[35] The party congress ordered that joint lists would only be organized with fellow socialist groups.[35] The Popular Socialists condemned Bolsheviks in their campaigning, whilst stressing the defencist line of their own party.[34]

Cooperative movement

The cooperative societies held an emergency congress on October 4, 1917, at which it was decided that they would contest the Constituent Assembly elections directly.[37][35] The congress discarded the notion of electoral pacts with non-socialist groups.[35] In the Petrograd election district, the list of cooperative candidates included only one notable figure, Alexander Chayanov. The other six candidates were largely unknown.[38]

National minorities

Most non-Russian voters opted for national minority parties. In the case of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party dominated the 4 electoral districts of the Ukrainian peasantry. Non-Ukrainian urban populations largely voted for Russian parties.[39] In the city of Kiev, the Ukrainian parties obtained 26% of the vote.[40] Over half a million soldiers and officers in the army and navy voted for Ukrainian parties supporting the Central Rada, making the Ukrainians the third force among military voters.[41]

However, in Belarus, Belarusian nationalist groups gathered less than 1% of the votes. In Transcaucasus the vote was divided between Georgians (voting for Mensheviks), Armenians (voting for the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, also known as Dashnaksiun) and Azeris (voting for Musavat and other Muslim groups). Tatar and Bashkir lists gathered 55% of the votes in Ufa.[39]

In July 1917 the First All-Kazakh Congress was held, establishing the Alash Party as a national political party. The party called for the 'liberation of the Kazakh people from colonial yoke'. Ahead of the election, party committees were formed in Semipalatinsk, Omsk, Akmolinsk and Uralsk.[42][43] In the Semirechie, Syr-Darya and Horde electoral districts Alash did not field lists of their own, but placed candidates of other Muslim lists.[44] Four days ahead of the vote the newspaper Qazaq published the Alash programme, including a call for a democratic federal republic with equality of nationalities.[45]

In 14 electoral districts, 2 or more Jewish lists were in the fray.[18] In Zhitomir, 5 out of 13 parties contesting were Jewish.[18] In Gomel 4 out of 11 parties were Jewish, in Poltava 5 out of 14.[18] Some 80% of the votes cast for Jewish parties went to Jewish national coalition lists.[18] The Folkspartey was the most enthusiastic proponent of Jewish national coalition lists.[18] These coalitions, generally contesting under titles such as 'Jewish National Bloc' or 'Jewish National Election Committee' also gathered Zionists and Orthodox Jews.[18] The candidates on these lists had vowed to form a common bloc in the Constituent Assembly and implement decisions of the All-Russian Jewish Congress.[46] The Jewish national lists were confronted by the various Jewish socialist parties; the General Jewish Labour Bund, the Jewish Social Democratic Labour Party (Poalei Zion) and the United Jewish Socialist Workers Party (Fareynikte). The Bund carried out 200 electoral meetings in White Russia (with a total attendance of about 127,000), and in the Ukraine the party held 2-3 electoral meetings weekly. In Odessa confrontations between socialist and non-socialist Jewish parties led to physical violence.[47] Jewish national lists elected Iu. D. Brutskus, A.M. Goldstein, the Moscow rabbi Yaakov Mazeh. V. I. Temkin, D. M. Kogan-Bernsthein, N. S. Syrkin and O. O. Gruzenberg (who was then close to Zionist circles). David Lvovich was elected on SR-Fareynikte list and the Bundist G.I. Lure was elected on a Menshevik-Bund list.[48]

The Buryat National Committee had previously been linked to the SRs, but ahead of the election relation was broken. Buryat SRs were not given prominent places on candidate lists, and the Buryat National Committee ended up contesting on its own.[49]

Others

Radical Democrats (rightists) got some 19,000 votes.[19]

Results

National results

- No fully complete account of the results of the 1917 election exists, as in several districts the holding of the election or the tallying of votes was interrupted. The numbers in the table below represent accounts from the voting in 70 out of 81 electoral districts, although not all of those districts have complete voting tallies. The tally of elected deputies stems from 74 districts.

| Party | Votes | % | Lists counted |

Seats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries[lower-roman 1] | 17,256,911 | 37.61 | 67 | 324 |

| Bolsheviks[lower-roman 2] | 10,671,387 | 23.26 | 64 | 183 |

| Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party and allies[lower-roman 3] | 5,819,395 | 12.68 | 16 | 110 |

| Kadets | 2,100,262 | 4.58 | 63 | 16 |

| Mensheviks[lower-roman 4] | 1,385,500 | 3.02 | 61 | 18 |

| Cossacks | 908,326 | 1.98 | 9 | 17 |

| Alash Orda | 767,632 | 1.67 | 4 | 15 |

| Musavat Party | 615,816 | 1.34 | 1 | 10 |

| Jewish national lists | 575,007 | 1.25 | 18 | 6 |

| Armenian Revolutionary Federation | 558,400 | 1.22 | 1 | 10 |

| Other Muslim lists[lower-roman 5] | 439,611 | 0.96 | 9 | |

| Muslims (Socialist-Revolutionaries) | 304,864 | 0.66 | 1 | 5 |

| Popular Socialists[lower-roman 6] | 240,791 | 0.52 | 39 | 1 |

| Chuvash | 235,587 | 0.51 | 3 | 3 |

| All-Russian Union of Landowners and Farmers | 229,264 | 0.50 | 20 | 0 |

| Polish lists | 211,272 | 0.46 | 7 | 2 |

| Orthodox lists | 210,973 | 0.46 | 18 | 0 |

| Bashkir Federalists | 200,161 | 0.44 | 3 | 5 |

| Germans | 194,623 | 0.42 | 9 | 1 |

| Muslim Shuro-Islamia | 183,558 | 0.40 | 2 | 5 |

| Peasants lists | 165,097 | 0.36 | 13 | 10 |

| Muslim Socialist Bloc | 159,770 | 0.35 | 1 | 3 |

| Muslim Socialist Committee of Kazan | 153,151 | 0.33 | 1 | 2 |

| Russian rightists[lower-roman 7] | 146,067 | 0.32 | 13 | 1 |

| Old Believers | 118,362 | 0.26 | 11 | 0 |

| Other Muslim socialist lists[lower-roman 8] | 100,890 | 0.22 | 6 | 0 |

| SR Defencists[lower-roman 9] | 99,542 | 0.22 | 5 | 0 |

| Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party[lower-roman 10] | 85,772 | 0.19 | 2 | 0 |

| Hummet | 84,748 | 0.18 | 1 | 1 |

| Right-wing socialist blocs[lower-roman 11] | 82,673 | 0.18 | 8 | 0 |

| All Fergana List of Soviet of Deputies of Muslim Organizations | 77,282 | 0.17 | 1 | 9 |

| Muinil Islam Society | 76,849 | 0.17 | 1 | 2 |

| Estonian Democratic Bloc | 68,085 | 0.15 | 1 | 2 |

| Ittehad | 66,504 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 |

| Estonian Labour Party | 64,704 | 0.14 | 1 | 2 |

| Buryat National Committee | 56,331 | 0.12 | 2 | 2 |

| Union of Ukrainian Peasants, Ukrainian Refugees and the Organization of Tatar Socialist Revolutionaries |

53,445 | 0.12 | 1 | 0 |

| Peasants Union-Popular Socialists alliance | 50,780 | 0.11 | 1 | 1 |

| German socialists | 42,148 | 0.09 | 1 | 0 |

| Lettish Peasant Union | 35,112 | 0.08 | 2 | 1 |

| United Jewish Socialist Labour Party (S.S. and E.S.) | 34,644 | 0.08 | 7 | 0 |

| Bund[lower-roman 12] | 32,986 | 0.07 | 3 | 0 |

| National Bloc (Ukrainians, Muslims, Poles and Lithuanians) | 29,821 | 0.06 | 1 | 0 |

| Uighur-Dungan alliance | 28,386 | 0.06 | 1 | 0 |

| Commercial-Industrial lists | 27,198 | 0.06 | 8 | 0 |

| Popular Socialist-Cooperative lists | 27,014 | 0.06 | 5 | 0 |

| Socialist-Federalists and Peasants of Latgale | 26,990 | 0.06 | 1 | 0 |

| Poalei Zion | 26,331 | 0.06 | 10 | 0 |

| Unity | 24,272 | 0.05 | 10 | 0 |

| Menshevik Defencists | 23,451 | 0.05 | 2 | 0 |

| Georgian National Democrats | 22,499 | 0.05 | 1 | 0 |

| Ukrainian Socialist-Federalists[lower-roman 13] | 22,253 | 0.05 | 3 | 0 |

| Menshevik-Internationalists[lower-roman 14] | 21,814 | 0.05 | 6 | 0 |

| Cooperative movement | 19,663 | 0.04 | 7 | 0 |

| Georgian Socialist-Federalists | 19,042 | 0.04 | 1 | 0 |

| Estonian Socialist Revolutionary Party | 17,726 | 0.04 | 1 | 0 |

| Estonian Radical Democratic Party | 17,022 | 0.04 | 1 | 0 |

| Estonian List | 15,963 | 0.03 | 1 | 0 |

| All Russian Peasants Union | 15,246 | 0.03 | 2 | 0 |

| Finnish Socialists | 14,807 | 0.03 | 1 | 0 |

| International Unity of Christian Democrats (Roman Catholics) | 14,382 | 0.03 | 1 | 0 |

| Dissident leftist SR lists[lower-roman 15] | 14,148 | 0.03 | 4 | 0 |

| Armenian Populist Party | 13,099 | 0.03 | 1 | 0 |

| Non-Partisan Public Figures | 12,050 | 0.03 | 1 | 0 |

| Leftist SRs-Ukrainian SRs-Polish Socialist Party alliance | 11,871 | 0.03 | 1 | 0 |

| Estonian Social Democratic Association | 9,244 | 0.02 | 1 | 0 |

| Siberian Autonomists | 9,224 | 0.02 | 2 | 0 |

| Greeks in Mariupol | 9,143 | 0.02 | 1 | 0 |

| Belarusian Socialist Assembly | 8,445 | 0.02 | 3 | 0 |

| Folkspartei[lower-roman 16] | 8,185 | 0.02 | 2 | 0 |

| Other Ukrainians[lower-roman 17] | 7,838 | 0.02 | 4 | 0 |

| All Russian League for Women's Equality | 7,676 | 0.02 | 2 | 0 |

| Landowner-Old Believer lists | 7,139 | 0.02 | 2 | 0 |

| Moldovan National Party | 6,643 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Petrograd organizations of the Ukrainian Soc.-Dem. Labour Party, the Ukrainian SRs and the United Jewish Socialist Labour Party (S.S. and E.S.) |

6,216 | 0.01 | 2 | 0 |

| Lettish Democrats-Nationalists | 5,881 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Latgallian Popular Committee and Latgallian Socialist Party of Working People | 5,118 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Independent Union of Workers, Soldiers and Peasants | 4,942 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Tsentroflot | 4,769 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Local citizens' groups | 4,725 | 0.01 | 3 | 0 |

| Democratic Non-partisan Group of Members of District Committees of Sergiev Posad | 4,497 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Bloc of Traders, Industrialists, Artisans and Homeowners | 4,421 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Ukrainian Toilers List | 3,810 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Christian Democratic Party | 3,797 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| E. Abramov | 3,776 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Lettish Soldiers | 3,386 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| White Russian Organizations | 2,523 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| National-Socialist Bloc (Ukrainian Socialist Bloc and Nationalist Bloc) | 2,346 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Pskov United Democratic Groups of Townspeople, Peasants and Workers | 2,337 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 |

| Officers' Union | 2,018 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| Agricultural-Artisan-Commercial-Industrial group | 2,001 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| Non-Partisan Group | 1,948 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| Nationalist Bloc | 1,708 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| List without title | 1,657 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| Homeowners and Landowners of Novgorod Governorate | 1,178 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| Ukrainian National Republican Group | 1,070 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| Toiling Peasants | 1,020 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| Employees of Government Agencies | 1,005 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| Other lists with less than 1000 votes | 5,833 | 0.01 | 13 | 0 |

| Muslim Organizations of Samarkand Oblast | ? | 1 | 4 | |

| Yakutian Labour Union of Federalists | ? | 1 | 1 | |

| Kalmyk | ? | 1 | 1 | |

| Unaccounted | 294,530 | 0.64 | ||

| Total | 45,879,381 | 100.00 | 629 | 767 |

| Sources: Radkey (1989),[50] Spirin (1987),[51] Hovannisian (1967),[52] Vestnik Evrazii (2004)[53] | ||||

- Includes lists such as the joint SR-Menshevik list in Olonets (although only the SR deputy is included in the seat tally), the general soviet list in Semirechie, the joint SR-Peasants Union list in Irkutsk, the joint SR-Ukrainian SR list in Poltava. The count does not include other joint SR-Ukrainian SR lists in Ukraine, except Poltava (where the SR-USR list confronted the main USR-sponsored list), nor does it include any of the dissident leftist or rightist SR lists.

- Includes all joint Bolshevik/Menshevik-Internationalist lists. Includes the joint Bolshevik-Menshevik list in Vologda, but not the joint Menshevik-Bolshevik list in Tobolsk (as the latter was reportedly dominated by Mensheviks).

- Includes all Ukrainian SR-led lists in Ukraine as well as the Ukrainian SR-led lists in the army districts

- Includes joint Menshevik-Bund lists, and the joint Menshevik-Bolshevik list in Tobolsk. This line does not include the votes from the joint SR-Menshevik list in Olonets, which elected one Menshevik deputy. However, the Menshevik from Olonets is included in the seat count.

- Includes the Astrakhan Muslim Group, the Kazan Governorate Muslim Assembly, the Orenburg Muslim Association, the Perm Muslims-Bashkirs, Perm Muslims, Taurida Muslims, Tobolsk Muslims, Western Transcaucasus Muslims, the Muslim National Council in Ufa, the Muslim-Democrats in Steppes, the Tatar list in Steppes, and the Muslim Union of Vyatka Governorate.

- Includes the joint list with the Cheremi National Union in Vyatka, which elected the sole Popular Socialist deputy nationwide. The various alliances with cooperative movements and other socialist groups are listed separately.

- Includes the different rightist and monarchist lists.

- Includes the All Muslim Socialist Bloc of Nizhny Novgorod, the Muslim Socialists in the Romanian Front, the Socialist Group of Muslim Soldiers of the South-Western Front, the Kirghiz Socialists in the Steppe district, the Party of the Muslim Socialist-Democratic Bloc in Tambov and the Muslim Socialist on the Western Front.

- Includes dissident right-wing SR lists that contested against the official SR party lists

- In many constituencies the party contested on the Ukrainian SR-led lists. This count is only for the 2 districts where the Ukrainian Social Democrats contested alone.

- Various local alliances of Popular Socialists, cooperatives, right-wing Mensheviks, right-wing SRs, Plekhanov's Unity group, etc.

- In most constituencies where the Bund was active, it contested on joint lists with the Mensheviks. This line only counts the 3 constituencies were the Bund ran its own lists.

- On 2 out of 3 lists, contested jointly with the Popular Socialists

- Does not include any results for joint lists with the Bolsheviks

- Includes the leftist dissident lists, that contested against the official SR party lists. In locations where the left faction of the SRs dominated the official party list, the result is included in the main SR count.

- In many locations the Folkspartei joined Jewish national lists.

- Includes 4 Ukrainian lists, outside of Ukraine, with unclear party identity.

Svyatitsky and Lenin

There are various different accounts of the election result, with varying numbers.[54] Many accounts on the election result originate from N. V. Svyatitsky's account, who was himself elected as an SR deputy to the Constituent Assembly.[54] His article was included in the one-year anniversary symposium of the Russian Revolution organized by the SR party (Moscow, Zemlya i Volya Publishers, 1918). Lenin (1919) describes Svyatitsky's account as extremely interesting. It presented results from 54 electoral districts, covering most of European Russia and Siberia. Notably is lacked details from the Olonets, Estonian, Kaluga, Bessarabian, Podolsk, Orenburg, Yakutsk, Don governorates, as well as Transcaucasus. All in all, Svyatitsky's account includes 36,257,960 votes. According to Lenin, the actual number from said 54 electoral districts was 36,262,560 votes. But Lenin reaffirms that between Svyatitisky's article and his account, the number of votes cast by party is largely identical.[55]

| Bloc | Votes | % | Party | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party of the Proletariat | 9,023,963 | 25 | Bolsheviks | 9,023,963 | 25 |

| Petty-bourgeoisie democratic parties | 22,616,064 | 62 | Socialist-Revolutionaries | 20,900,000 | 58 |

| Mensheviks | 668,064 | 2 | |||

| Popular Socialists | 312,000 | 1 | |||

| Unity | 25,000 | ||||

| Cooperative | 51,000 | ||||

| Ukrainian Soc.-Dem. | 95,000 | ||||

| Ukrainian Socialists | 507,000 | 1 | |||

| German socialists | 44,000 | ||||

| Finnish Socialists | 14,000 | ||||

| Parties of landowners and bourgeoisie | 4,539,639 | 13 | Kadets | 1,856,639 | 5 |

| Association of Rural Proprietors and Landowners | 215,000 | 1 | |||

| Right groups | 292,000 | 1 | |||

| Old Believers | 73,000 | ||||

| Jews | 550,000 | 2 | |||

| Muslims | 576,000 | 2 | |||

| Bashkirs | 195,000 | ||||

| Letts | 67,000 | ||||

| Polish | 155,000 | ||||

| German | 130,000 | ||||

| White Russians | 12,000 | ||||

| Lists of various groups and organizations | 418,000 | 1 |

Radkey and Spirin

More recent studies often use Svyatitsky's 1918 account as their starting point for further elaboration.[54] L. M. Spirin (1987) uses local newspapers and Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian archival holdings to supplement Svyatitsky, whereas U.S. historian Oliver Henry Radkey predominately uses local newspapers as sources.[54] According to Rabinovitch (2016), Spirin's account is the most complete.[54] According to Arato (2017), U.S. scholar Radkey is the most serious historian on the 1917 election.[56]

Radkey uses a number of uses broad categories in presenting the result party-wise: SRs (sometimes distinguished between left/right), Bolsheviks, Mensheviks (sometimes divided between Menshevik-Internationalists and Right-wing pro-war Mensheviks), Other Socialists (with subcategories) Kadets, Special interests (including subcategories peasants, landowners, Cossacks, middle-class, others), Religious (Orthodox, Old Believers, others), Ukrainian (with subcategories), Turkic-Tatar (with subcategories), Other Nationalities (with subcategories).[57]

Deputies elected

Protasov (2004) presents the party affiliation of 765 deputies elected from 73 electoral districts: 345 SRs, 47 Ukrainian SRs, 175 Bolsheviks, 17 Mensheviks, 7 Ukrainian Social Democrats, 14 Kadets, 2 Popular Socialists, another 32 Ukrainian socialists (possibly SRs or social democrats), 13 Muslim Socialists, 10 Dashnaks, 68 from other national parties, 16 Cossacks, 10 Christians and one clergyman. Another 55 deputies were supposed to have been elected from another 8 electoral districts.[19] Of the over 700 deputies known by name, over 400 participated at first session and only session of the Constituent Assembly (240 of the assembled belonged to the SR bloc).[58]

Several prominent politicians had stood as candidates in multiple electoral districts. The Central Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) had named Lenin as their candidate in 5 districts: Petrograd City, Petrograd Province, Ufa, Baltic Fleet and Northern Front. Lenin was also nominated from Moscow City.[59] On November 27 (December 10) the All-Russia Committee for Elections to the Constituent Assembly requested members of the Constituent Assembly who had been returned by several areas to present a written statement indicating the electoral district for which they accepted election. Having been elected by several areas, Lenin, too, presented such a statement.[59] Lenin opted to represent the Baltic Fleet in the Constituent Assembly. In case an elected candidate didn't send in such a statement, the All-Russian Election Commission for the Constituent Assembly would consider the person elected from the district where he obtained the highest number of votes.[60]

Ballots

A sheet with samples of the ballots of different parties contesting the Petrograd electoral district. The sheet had been distributed by the electoral authorities prior to the vote, urging voters to cut out their preferred ballot and bring it to the polling station.[61] The ballots include the listing of names of candidates, with their addresses. The Bolshevik List (No. 2) is headed by Lenin, the Menshevik List (No. 3) is headed by Mikhail Liber. The Estonian List (No. 4) ballot is bilingual, with the candidate listing appearing in both Russian and Estonian (the latter written in Fraktur script).

A sheet with samples of the ballots of different parties contesting the Petrograd electoral district. The sheet had been distributed by the electoral authorities prior to the vote, urging voters to cut out their preferred ballot and bring it to the polling station.[61] The ballots include the listing of names of candidates, with their addresses. The Bolshevik List (No. 2) is headed by Lenin, the Menshevik List (No. 3) is headed by Mikhail Liber. The Estonian List (No. 4) ballot is bilingual, with the candidate listing appearing in both Russian and Estonian (the latter written in Fraktur script). Bolshevik ballot for Petrograd City. The list carries the title Central Committee of Military Organizations, Petrograd Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks), Committee of the Social Democracy of Poland and Lithuania, Central Committee of the Social Democracy of Latvia. The list has 18 candidates, headed by Lenin, Zinoiev, Trotsky, Kamenev, Alexandra Kollontai and Stalin.

Bolshevik ballot for Petrograd City. The list carries the title Central Committee of Military Organizations, Petrograd Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks), Committee of the Social Democracy of Poland and Lithuania, Central Committee of the Social Democracy of Latvia. The list has 18 candidates, headed by Lenin, Zinoiev, Trotsky, Kamenev, Alexandra Kollontai and Stalin. Ballot of the Chernigov Committee of the Jewish Social Democratic Labour Party (Poalei Zion). The list was headed by Ber Borochov.

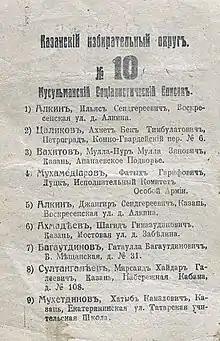

Ballot of the Chernigov Committee of the Jewish Social Democratic Labour Party (Poalei Zion). The list was headed by Ber Borochov. The ballot of the Muslim Socialist List in Kazan

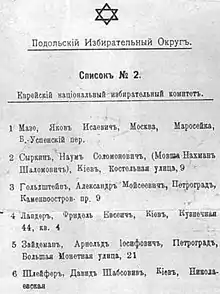

The ballot of the Muslim Socialist List in Kazan The ballot of the Jewish National Electoral Committee in the Podolia electoral district. The ballot carries a star of David.

The ballot of the Jewish National Electoral Committee in the Podolia electoral district. The ballot carries a star of David. Ballot of the All-Russian Women's Equal Rights League (List no. 7) in Petrograd City

Ballot of the All-Russian Women's Equal Rights League (List no. 7) in Petrograd City

Electoral campaign materials

Voters inspecting campaign posters, Petrograd

Voters inspecting campaign posters, Petrograd Kadet electoral poster, illustrating a mounted warrior confronting a monster. The monster represents anarchy, the mounted warrior democracy.

Kadet electoral poster, illustrating a mounted warrior confronting a monster. The monster represents anarchy, the mounted warrior democracy. Poster issued by the Petrograd Commercial-Industrial Union, calling traders, producers and craftsmen to vote for the Kadet List 2

Poster issued by the Petrograd Commercial-Industrial Union, calling traders, producers and craftsmen to vote for the Kadet List 2 Kadet election poster. A female horse-rider, carrying a sword and a shield with the word Svoboda ('Freedom').

Kadet election poster. A female horse-rider, carrying a sword and a shield with the word Svoboda ('Freedom'). Kadet election poster, showing a woman in traditional garb.[62] Work by Piotr Buchkin.

Kadet election poster, showing a woman in traditional garb.[62] Work by Piotr Buchkin. Bulletin issued by the Kadet Party branch in Harbin, campaigning for its candidate D. Horvath for the Chinese Eastern Railway seat

Bulletin issued by the Kadet Party branch in Harbin, campaigning for its candidate D. Horvath for the Chinese Eastern Railway seat Poster urging voters to only vote for Social Democrats, with reference to a List 4

Poster urging voters to only vote for Social Democrats, with reference to a List 4.jpg.webp) Social Democratic election poster, illustrating a lighthouse sending out beacons. The list number is left vacant, allowing party branches in different parts of the country to adapt the poster with their local list number.

Social Democratic election poster, illustrating a lighthouse sending out beacons. The list number is left vacant, allowing party branches in different parts of the country to adapt the poster with their local list number. Menshevik electoral poster

Menshevik electoral poster A Russian-Yiddish Fareynikte (United Jewish Socialist Workers Party) poster, announcing an electoral campaign meeting

A Russian-Yiddish Fareynikte (United Jewish Socialist Workers Party) poster, announcing an electoral campaign meeting A SR election poster, calling on Peasants, Workers and Soldiers to vote for the party. The slogan Earth and Will appears twice in the poster, and the letters SR figure on the bell.

A SR election poster, calling on Peasants, Workers and Soldiers to vote for the party. The slogan Earth and Will appears twice in the poster, and the letters SR figure on the bell.

Dissolution of Constituent Assembly by Bolsheviks

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) convened only for 13 hours, from 4 p.m. to 5 a.m., 18–19 January [O.S. 5–6 January] 1918, whereupon it was dissolved by the Bolshevik-controlled All-Russian Central Executive Committee,[63] making the Bolshevik Third All-Russian Congress of Soviets the new governing body of Russia.[64][65][66]

See also

Notes

- Some districts had polling on alternate days.

References

- Dando, William A. (June 1966). "A Map of the Election to the Russian Constituent Assembly of 1917". Slavic Review. 25 (2): 314–319. doi:10.2307/2492782. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2492782. S2CID 156132823.

- Концепция социалистической демократии: опыт реализации в СССР и современные перспективы в СНГ

- Ulam (1998), p. 397; Sakwa (1999), p. 73; Judson (1998), p. 229; Marples (2010), p. 38; Hough & Fainsod (1979), pp. 80–81; Dowlah & Elliott (1997), p. 18

- Soviet Union at Encyclopedia Britannica

- Grant, Alex (1 November 2017). "Top 10 lies about the Bolshevik Revolution". In Defence of Marxism.

- Novack, George (1971). Democracy and Revolution. Pathfinder. pp. 307–347. ISBN 978-0-87348-192-2.

- Cliff, Tony. "Revolution Besieged. The Dissolution of the Constituent Assembly)". www.marxists.org.

- Brenton, Tony (2017). Was Revolution Inevitable?: Turning Points of the Russian Revolution. Oxford University Press. pp. 152–155. ISBN 978-0-19-065891-5.

- Ruthchild, Rochelle Goldberg (2010). Equality and Revolution. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. xviii, 207. ISBN 978-0-8229-7375-1.

- Korolikov, O. P.. Выборы в Учредительное собрание в Псковской губернии (1917 г.) Archived 2019-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Lenin, V. I. (2001). Democracy and Revolution. Resistance Books. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-876646-00-4.

- Wade 2004, pp. 256–257.

- Mawdsley, Evan; Munck, Thomas (1993). Computing for Historians: An Introductory Guide. Manchester University Press. pp. 117, 119. ISBN 978-0-7190-3548-7.

- Maksimov, Konstantin Nikolaevich (1 January 2008). Kalmykia in Russia's Past and Present National Policies and Administrative System. Central European University Press. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-963-9776-17-3.

- Лев Григорьевич Протасов (1997). Всероссийское учредительное собрание: история рождения и гибели. РОССПЭН. p. 162. ISBN 9785860041172.

- Oliver Henry Radkey (1989). Russia goes to the polls: the election to the all-Russian Constituent Assembly, 1917. Cornell University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8014-2360-4.

- Swain, Geoffrey (24 February 2014). Trotsky and the Russian Revolution. Routledge. p. xiv. ISBN 978-1-317-81278-4.

- Simon Rabinovitch (1 October 2016). Jewish Rights, National Rites: Nationalism and Autonomy in Late Imperial and Revolutionary Russia. Stanford University Press. pp. 233–235. ISBN 978-0-8047-9303-2.

- Wade 2004, p. 259.

- Wade 2004, p. 260.

- Radkey, Oliver Henry (1989). Russia goes to the polls: the election to the all-Russian Constituent Assembly, 1917. Cornell University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8014-2360-4.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila (28 February 2008). The Russian Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-19-923767-8.

- Smith, Scott Baldwin (2011). Captives of Revolution: The Socialist Revolutionaries and the Bolshevik Dictatorship, 1918–1923. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 10, 98. ISBN 978-0-8229-7779-7.

- D'Agostino, Anthony (2011). The Russian Revolution, 1917-1945. ABC-CLIO. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-313-38622-0.

- Smith, Stephen Anthony (2017). Russia in Revolution: An Empire in Crisis, 1890 to 1928. Oxford University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-19-873482-6.

- Llewellyn, Jennifer. "The Left SRs". THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION. Alpha History. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- Serge, Victor (15 January 2017). Year One of the Russian Revolution. Haymarket Books. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-60846-609-2.

- Smith, Scott Baldwin (2011). Captives of Revolution: The Socialist Revolutionaries and the Bolshevik Dictatorship, 1918–1923. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 10–11, 14–35. ISBN 978-0-8229-7779-7.

- Rabinowitch, Alexander (2008). The Bolsheviks in Power: The First Year of Soviet Rule in Petrograd. Indiana University Press. pp. 3, 89. ISBN 978-0-253-22042-4.

- Nimtz, August H. (13 March 2014). Lenin's Electoral Strategy from 1907 to the October Revolution of 1917: The Ballot, the Streets—or Both. Springer. pp. 133, 138. ISBN 978-1-137-38995-4.

- McAuley, Mary (1991). Bread and Justice: State and Society in Petrograd, 1917-1922. Clarendon Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-19-821982-8.

- Brovkin, Vladimir N. (1991). The Mensheviks After October: Socialist Opposition and the Rise of the Bolshevik Dictatorship. Cornell University Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-8014-9976-3.

- Wade, Rex A. (2 February 2017). The Russian Revolution, 1917. Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-107-13032-6.

- Hickey, Michael C. (2011). Competing Voices from the Russian Revolution. ABC-CLIO. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-313-38523-0.

- Swain, Geoffrey (26 November 2013). The Origins of the Russian Civil War. Routledge. pp. 46, 85. ISBN 978-1-317-89912-9.

- Rabinovitch, Simon (1 October 2016). Jewish Rights, National Rites: Nationalism and Autonomy in Late Imperial and Revolutionary Russia. Stanford University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-8047-9303-2.

- Browder, Robert Paul; Kerensky, Aleksandr Fyodorovich (1961). The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents. Stanford University Press. p. 1730.

- Gerasimov, Ilya (29 September 2009). Modernism and Public Reform in Late Imperial Russia: Rural Professionals and Self-Organization, 1905-30. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-230-22947-1.

- Kappeler, Andreas (27 August 2014). The Russian Empire: A Multi-ethnic History. Routledge. p. 363. ISBN 978-1-317-56810-0.

- Liber, George O. (2016). Total Wars and the Making of Modern Ukraine, 1914-1954. University of Toronto Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-4426-2708-6.

- The Ukrainian Quarterly. Ukrainian Congress Committee of America. 1957. p. 327.

- Sabol, S. (13 March 2003). Russian Colonization and the Genesis of Kazak National Consciousness. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-230-59942-0.

- Dudolgnon, Stephane A.; Hisao, Komatsu (5 November 2013). Islam In Politics In Russia. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-136-88878-6.

- Н. Н. Алеврас (1995). Rossiya i Vostok: Rossiya mezhdu Yevropoy i Aziyey. Natsional'nyy vopros i politicheskiye dvizheniya Россия и Восток: Россия между Европой и Азией. Национальный вопрос и политические движения [Russia and the East: Russia between Europe and Asia. National question and political movements] (in Russian). Челябинский гос. унив. p. 157.

- Rottier, Pete (2005). Creating the Kazak nation: the intelligensia's quest for acceptance in the Russian empire, 1905-1920. University of Wisconsin-Madison. p. 337.

- Malamat, Abraham (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. p. 965. ISBN 978-0-674-39731-6.

- Gitelman, Zvi Y. (8 March 2015). Jewish Nationality and Soviet Politics: The Jewish Sections of the CPSU, 1917-1930. Princeton University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-1-4008-6913-8.

- Budnitskii, Oleg (24 July 2012). Russian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917-1920. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8122-0814-6.

- Sablin, Ivan (5 February 2016). Governing Post-Imperial Siberia and Mongolia, 1911–1924: Buddhism, Socialism and Nationalism in State and Autonomy Building. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-317-35894-7.

- Radkey, Oliver Henry (1989). Russia goes to the polls: the election to the all-Russian Constituent Assembly, 1917. Cornell University Press. pp. 148–160. ISBN 978-0-8014-2360-4.

- Л. М. Спирин (1987). Rossiya 1917 god: iz istorii bor'by politicheskikh partiy Россия 1917 год: из истории борьбы политических партий [Russia 1917: from the history of the struggle of political parties] (in Russian). Мысль. pp. 273–328.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1967). Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. University of California Press. pp. 108, 288. ISBN 978-0-520-00574-7.

- Vestnik Yevrazii Вестник Евразии [Bulletin of Eurasia] (in Russian). изд-во дi-дик. 2004. p. 120.

- Rabinovitch, Simon (1 October 2016). Jewish Rights, National Rites: Nationalism and Autonomy in Late Imperial and Revolutionary Russia. Stanford University Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-8047-9303-2.

- Lenin, V. I. (1919). The Constituent Assembly Elections and The Dictatorship of the Proletariat – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Arato, Andrew (30 November 2017). The Adventures of the Constituent Power. Cambridge University Press. p. 421. ISBN 978-1-107-12679-4.

- Radkey, Oliver Henry (1989). Russia goes to the polls: the election to the all-Russian Constituent Assembly, 1917. Cornell University Press. pp. 148–157. ISBN 978-0-8014-2360-4.

- Backes, Uwe; Kailitz, Steffen (23 October 2015). Ideocracies in Comparison: Legitimation – Cooptation – Repression. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-317-53545-4.

- Vladimir Ilʹich Lenin (1970). Collected Works: October 1917-Nov.1920. Lawrence & Wishart. p. 467.

- Browder, Robert Paul; Kerensky, Aleksandr Fyodorovich (1961). The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents. Stanford University Press. p. 462.

- MK.ru. Москвичи могут увидеть тех, кто устраивал знаменитую русскую революцию

- Wade, Rex A. (21 April 2005). The Russian Revolution, 1917. Cambridge University Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-521-84155-9.

- Ulam (1998), p. 397; Sakwa (1999), p. 73; Judson (1998), p. 229; Hough & Fainsod (1979), p. 80

- Marples 2010, p. 38.

- Hough & Fainsod 1979, p. 81.

- Dowlah & Elliott 1997, p. 18.

Bibliography

- Dowlah, Alex F.; Elliott, John E. (1997). The Life and Times of Soviet Socialism. Praeger.

- Hough, Jerry F.; Fainsod, Merle (1979). How the Soviet Union is Governed. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674410305.

- Judson, William (1998). Salzman, Neil V. (ed.). Russia in War and Revolution: General William V. Judson's Accounts from Petrograd, 1917-1918. Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0873385978.

- Marples, David R. (2010). Russia in the Twentieth Century: The Quest for Stability. Routledge. ISBN 9781408228227.

- Sakwa, Richard (1999). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415122900.

- Ulam, Adam Bruno (1998). The Bolsheviks: the intellectual and political history of the triumph of communism in Russia: with a new preface. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674078307.

- Wade, Rex A. (31 July 2004). Revolutionary Russia: New Approaches to the Russian Revolution of 1917. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-39764-8.

Further reading

- Badcock, Sarah (2001). "'We're for the Muzhiks' Party!' Peasant Support for the Socialist Revolutionary Party During 1917". Europe-Asia Studies. 53 (1): 133–149. doi:10.1080/09668130124440. S2CID 153536229.

- Rabinovitch, Simon (2009). "Russian Jewry goes to the polls: an analysis of Jewish voting in the All‐Russian Constituent Assembly Elections of 1917". East European Jewish Affairs. 39 (2): 205–225. doi:10.1080/13501670903016316. S2CID 162657744.

- Radkey, Oliver Henry (1989). Russia goes to the polls: the election to the all-Russian Constituent Assembly, 1917. Cornell University Press.

- Smith, Scott Baldwin (2011). Captives of Revolution: The Socialist Revolutionaries and the Bolshevik Dictatorship, 1918–1923. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Von Hagen, Mark (1990). Soldiers in the proletarian dictatorship: the Red Army and the Soviet socialist state, 1917-1930. Cornell University Press.