Barefoot running

Barefoot running, also called "natural running", is the act of running without footwear. With the advent of modern footwear, running barefoot has become less common in most parts of the world but is still practiced in parts of Africa and Latin America. In some Western countries, barefoot running has grown in popularity due to perceived health benefits.[1]

Scientific research into the practice of running barefoot has not reached a clear consensus regarding its risks or its benefits.[2] While footwear might provide protection from cuts, bruises, impact and weather, proponents argue that running barefoot reduces the risk of chronic injuries (notably repetitive stress injuries) caused by heel striking in padded running shoes.

The barefoot movement has prompted some manufacturers to introduce minimalist shoes, thin-soled and flexible shoes such as traditional moccasins and huaraches for minimalist running.

History

Throughout most of human history, running was performed while barefoot or in thin-soled shoes such as moccasins. This practice continues today in Kenya and among the Tarahumara people of northern Mexico.[3] Historians believe that the runners of Ancient Greece ran barefoot. According to legend, Pheidippides, the first marathoner, ran from Athens to Sparta in less than 36 hours.[4] After the Battle of Marathon, it is said he ran straight from the battlefield to Athens to inform the Athenians of the Greek victory over Persia.[5]

Dr. Charles Robbins who won 11 U.S. national championships including the Yonkers Marathon in 1944, finished the Boston Marathon 20 times, with a third place in 1944, and was an alternate to the marathon team at the 1948 London Olympics often ran races barefoot.[6]

In 1960, Abebe Bikila of Ethiopia won the Olympic marathon in Rome barefoot setting a new world record after discovering that Adidas, the Olympic shoe supplier, had run out of shoes in his size. He was in pain because he had received shoes that were too small, so he decided to simply run barefoot; Bikila had trained running barefoot prior to the Olympics.[7] He would go on to defend his Olympic title four years later in Tokyo while wearing shoes and setting a new world record.

British runner Bruce Tulloh competed in many races during the 1960s while barefoot, and won the gold medal in the 1962 European Games 5,000-metre race.[8]

In the 1970s, Shivnath Singh, one of India's greatest long distance runners, was known for always running barefoot with only tape on his feet.[9]

During the 1980s, a South African runner, Zola Budd, became known for her barefoot running style as well as training and racing barefoot. She won the 1985 and 1986 IAAF World Cross Country Championships and competed in the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.[10]

Kenyan runner Tegla Loroupe began running barefoot 10 km (6.2 mi) to and from school every day at the age of seven. She performed well in contests at school, and in 1988, won a prestigious cross country barefoot race. She went on to compete, both barefoot and shod, in several international competitions, marathons, and half-marathons. She won the Goodwill Games over 10,000 metres, barefoot, and was the first African woman to win the New York City Marathon in 1994, winning again in 1998.[11]

_-_TIMEA.jpg.webp)

In the early 21st century, barefoot running has gained a small yet significant following on the fringe of the larger running community. Organizers of the 2010 New York City Marathon saw an increase in the number of barefoot runners participating in the event.[12] The practice saw a surge in popularity after the 2009 publication of Christopher McDougall's book, Born to Run, promoting the practice.[13][14] In the United States, the Barefoot Runners Society was founded in November 2009 as a national club for unshod runners. By November 2010, the organization claimed 1,345 members, nearly double the 680 members it had when it was founded.[12]

One barefoot runner, Rick Roeber, has been running barefoot since 2003, and has run more than 50 marathons, 2 ultra-marathons of 40 miles, and over 17,000 miles (27,000 km) all barefoot.[15] Other prominent barefoot runners include Ken Bob Saxton, known as the "godfather of barefoot running", and Todd Byers, a barefoot marathon runner from Seattle who has run over 100 marathons barefoot.[16] On 8 December 2006, Nico Surings of Antwerp, Belgium, became the fastest person to run 100 meters (330 feet) on ice while barefoot, completing the task in 17.35 seconds.[17] And on 12 December 2010, the Barefoot Runners of India Foundation (BRIF) organised a 21 km (13 mi) barefoot half-marathon at Kharghar near the Indian city of Mumbai. The run had 306 participants.[18]

On 1 April 2012, runner Rae Heim embarked on a 3,000-plus mile barefoot run from Boston, Massachusetts, finishing on 14 November in Manhattan Beach, California.[19] She raised money for a Tennessee-based organization, Soles4Souls, who delivered one pair of shoes to needy children for each dollar raised by Heim.[20] And on 23 June 2012, Robert Knowles, of Brisbane, Australia, set two Guinness World Records for both the Fastest 100 km Barefoot and the Longest Distance Run Barefoot in 24 Hours, as part of the Sri Chinmoy Sydney 24 Hour Race. He logged 166.444 km (103.424 mi), or 416 laps on the Blacktown International Sportspark track, barefoot.[21] Later this record was surpassed by several runners, most recently Andrew Snope of Los Angeles, CA who ran 232.72 km (146.6 miles) on 8 December 2018 at the Desert Solstice Track Invitational 24-hour race in Phoenix, Arizona. On 13 August 2017, barefoot runner Teage O'Connor broke 100 km record as part of a fundraiser for the environmental education center he operates, Crow's Path. He ran 100 km barefoot on UVM's track in 7 hours 13 minutes and 25 seconds.[22] In December 2017, O'Connor ran 100 miles in 14 hours 22 minutes.[23]

Health and medical implications

Since the latter half of the 20th century, there has been scientific and medical interest in the benefits and harm involved in barefoot running. The 1970s, in particular, saw a resurgent interest in jogging in western countries and modern running shoes were developed and marketed.[24]

Since then, running shoes have been blamed for the increased incidence of running injuries and this has prompted some runners to go barefoot.[13] However, the American Podiatric Medical Association has stated that there is not enough evidence to support such claims and has urged would-be barefoot runners to consult a podiatrist before doing so.[25] The American Diabetes Association has urged diabetics and other people with reduced sensation in their feet not to run barefoot, citing an increased likelihood of foot injury.[26]

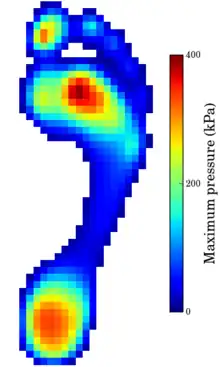

The structure of the human foot and lower leg is very efficient at absorbing the shock of landing and turning the energy of the fall into forward motion, through the springing action of the foot's natural arch. Scientists studying runners' foot motions have observed striking differences between habitually shod runners (wearing shoes) and barefoot runners. The foot of habitually shod runners typically lands with an initial heel strike, while the foot of a barefoot runner lands with a more springy step on the middle, or on the ball of the foot.[27] In addition, the strike is shorter in duration and the step rate is higher. When looking at the muscle activity (electromyography), studies have shown a higher pre-activation of the plantar flexor muscles when running barefoot.[28] Indeed, since muscles' role is to prepare the locomotor system for the contact with the ground, muscle activity before the strike depends on the expected impact. Forefoot strike, shorter step duration, higher rate and higher muscle pre-activation are techniques to reduce stress of repetitive high shocks.[28] This avoids a very painful and heavy impact, equivalent to two to three times the body weight.[24]

"People who don't wear shoes when they run have an astonishingly different strike", said Daniel E. Lieberman, professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University and co-author of a paper appearing in the journal Nature. "By landing on the middle or front of the foot, barefoot runners have almost no impact collision, much less than most shod runners generate when they heel-strike."[29]

However, a prospective study from 2019 found that when habituated to barefoot running (for two months with 15 minutes per week of barefoot running), participants exhibited higher vertical loading rates than shod runners, contradicting Lieberman and the asserted injury prevention potential of barefoot running.[30] Still, another study from 2018 showed that the highest load rates are found in injured heel striking runners.[31]

Also, when comparing different populations of habitually barefoot runners, not all of them favor the forefoot strike. A 2012 study by Hatala et al. focusing on 38 runners of the Daasanach tribe in Kenya found that a majority of runners favored a heel strike instead of a forefoot strike.[32] Presently, Hatala and Lieberman are comparing their data, but Lieberman did note that his study, which focused on the Kalenjin people, also found some barefoot runners favoring a heel strike as well. He also said that the Daasanach people were primarily, "tall, lanky goat-herders who don't run nearly as much as the Kalenjin, who own many of the world's distance running records."[33]

The longitudinal (medial) arch of the foot also may undergo physiological changes upon habitually training barefoot. The longitudinal arch has been observed to decrease in length by an average of 4.7 mm, suggesting activation of foot musculature when barefoot that is usually inactive when shod. These muscles allow the foot to dampen impact and may remove stress from the plantar fascia.[34] In addition to muscle changes, barefoot running also reduces energy use – oxygen consumption was found to be approximately 4% higher in shod versus barefoot runners. Better running economy observed when running barefoot compared to running with shoes can be explained by a better use of the muscle elasticity. In fact, reduction of contact time and higher pre-stretch level can enhance the stretch shortening cycle behavior of the plantar flexor muscles and thus possibly allow a better storage and restitution of elastic energy compared to shod running.[28][35]

However, running shoes also provide several advantages, including protection of the runner from puncture wounds, bruising, thermal injuries from extreme weather conditions, and overuse injuries.[36] Transitioning to a barefoot running style also takes time to develop, due to the use of different muscles involved. Doctors in the United States have reported an increase in such injuries as pulled calf muscles, Achilles tendinitis, and metatarsal stress fractures, which they attribute to barefoot runners attempting to transition too fast.[37]

The running shoe itself has also been examined as a possible cause of many injuries associated with shod running. One 1991 study found that wearers of expensive running shoes that are promoted as having special features, such as added cushioning or pronation correction, were injured significantly more frequently than runners wearing inexpensive shoes.[13] It has also been found that running in conventional running shoes increases stress on the knee joints up to 38%, although it is still unclear if this leads to a higher rate of heel injuries or not.[38][39][40] One study suggests that there is no evidence that cushioning or pronation control in shoes reduces injury rates or reduces performance.[41] It was also found that the belief that one's shoes have increased cushioning had no effect on increasing or decreasing ground reaction forces during walking.[42] Modern running shoes can also increase joint torque at the hip, knee, and ankle, and the authors of the study even suggest that running in high heels might be better than modern running shoes.[43] Improperly fitting shoes may also result in injuries such as a subungual hematoma – a collection of blood underneath the toenail. This may also be known as "runner's toe" or "tennis toe".[44] However, a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) suggested that heavier runners might be at an increased risk for injury in minimalist shoes (designed to mimic barefoot running) as compared to conventional footwear.[45]

Minimal footwear

The alternative to going barefoot is to wear thin shoes with minimal padding. This is what runners wore for thousands of years before the 1980s when the modern running shoe was invented.

Shoes, such as moccasins or thin sandals, permit a similar gait as barefoot, but protect the feet from cuts, abrasion and soft sticky matter.[29] The Tarahumara wear thin-soled sandals known as huaraches. These sandals have a single long lace with a thin sole made from either recycled tires, commercially available replacement outsole rubber, or leather. The practice of wearing light or no shoes while running may be termed "minimalist running".[46]

Plimsolls were worn by children in the United Kingdom for physical education classes as well as by soldiers for PT. Inexpensive "dime store" plimsolls have very thin footbeds (3mm elastomer/rubber outsole, 1mm card, 2mm eva foam) and no heel lift or stiffening.

Some modern shoe manufacturers have recently designed footwear to mimic the barefoot running experience, maintaining optimum flexibility and natural walking while also providing some degree of protection. The purpose of these "minimalist shoes" is to allow one's feet and legs to feel more subtly the ground, allowing more accurate adjustments in running style.[47]

Most minimalist running shoes are based within a scale from 1–10, where 1 is barefoot and 10 is a typical athletic shoe sole. The Vibram FiveFingers has separate slots for each toe and no cushioning.[48][49] Traditional racing flats are fairly minimal; offering good ground feel and control. Conversely, the Nike Free line of footwear, designed as a 5, features a segmented sole which provides greater flexibility while still having an amount of cushioning,[50][51] Saucony introduced the Kinvara line of shoes which feature a dropped sole, which halves the thickness of the sole and removes much of the heel cushioning, to encourage more of a midfoot strike for the foot.[52][53] Though not the only company to produce socks incorporating Kevlar in the yarn, the Swiss Barefoot Company's Protection Socks are marketed for barefoot use.[54] Following the trend, by 2011, minimalist running shoes have been made available by most of the major shoe manufacturers.[55]

The United States Army has banned the use of toe shoes for image reasons.[56] However, many other barefoot-inspired shoes that do not feature individual toes can still be used in its place. The United States Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and United States Coast Guard, however, have approved minimalist shoes, including toe shoes, to be used during physical training.[57][58]

Sales of minimalist running shoes have grown into a $1.7 billion industry. Sales of minimalist running shoes grew from $450,000 in 2006 to $59 million in 2012, and grew 303% from November 2010 through November 2012, compared to a 19% increase in the overall sales of running shoes during the same time period.[33][59] In the summer of 2012, both Vibram and Adidas were sued in the United States regarding allegations of deceptive claims of increased training efficiency, foot strength, and decreased risk of injury resulting from use of their minimalist running shoes.[60][61] These lawsuits follow on the heels of prior settlements by Skechers and Reebok with the Federal Trade Commission over claims that their toning shoes strengthen the body in ways no shoes ever had before.[62] In 2014 Vibram settled a $3.75 million lawsuit over false advertising of the FiveFingers shoes.[63]

References

- Reader, Andrew. "2 Rules For Beginning Barefoot Running (And Avoiding Injury)." Breaking Muscle. N.p., n.d. Web. 4 Nov. 2014. <http://breakingmuscle.com/running/2-rules-for-beginning-barefoot-running-and-avoiding-injury>.

- Perkins, Kyle P.; Hanney, William J.; Rothschild, Carey E. (November 2014). "The risks and benefits of running barefoot or in minimalist shoes: a systematic review". Sports Health. 6 (6): 475–480. doi:10.1177/1941738114546846. ISSN 1941-7381. PMC 4212355. PMID 25364479.

- McDougall, Christopher (19 April 2009). "What Ruins Running". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- Krentz, Peter (2010). The Battle of Marathon. USA: Achorn International, Inc. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-300-12085-1.

- Turpin, Zachary. "Winning the Boston Marathon, With or Without Shoes". Book of Odds. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "The Secret To His Success: It's All in the Feet". The New York Times. 4 August 2002. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- Redding, Cliff (July 1998). "In Africa, Sports is the Thing". The Crisis: 62–63.

- Kerton, Nigel (29 October 2010). "Marlborough track star's marathon bid at 75". thisiswiltshire.co.uk. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- Robillard, Jason (2010). The Barefoot Running Book Second Edition: A Practical Guide to the Art and Science of Barefoot and Minimalist Shoe Running. Allendale, Michigan: Barefoot Running University. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-615-37688-2.

- Turok, Karina; Orford, Margie (2006). Life and Soul: Portraits of Women Who Move South Africa. South Africa: Juta and Company, Ltd. p. 64. ISBN 978-1770130432.

- "About Tegla Loroupe". Tegla Loroupe Peace Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- Thomas, Katie (2 November 2010). "Running Shorts. Singlet. Shoes?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- McDougall, Christopher (2011) [2009]. Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen. New York City: Vintage Books. pp. 168, 172. ISBN 978-0-307-27918-7.

born to run.

- "Barefoot Running". The New York Times. 4 October 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- Fetterman, Debbie (28 January 2010). "Runner still paves way with shoeless approach". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- Wood, Terry (24 November 2011). "Going barefoot feels natural to Seattle Marathon participant". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Fastest run 100 metres barefoot on ice". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Gopalkrishnan, Krithika (16 November 2010). "World's 1st barefoot half-marathon in Mumbai". Daily News & Analysis. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Collins, Melissa (11 December 2012). "18-Year-Old Runs Across the Country Barefoot". Runner's World.

- Danner, Todd (14 November 2012). "A sole mission: Carroll girl runs barefoot across United States to raise money for shoes". Bulletin Review. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- "Barefoot Record". Westside News. 10 October 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- "100km barefoot world record!! – Crow's Path". crowspath.org. 14 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Desert Solstice, 100 miles".

- Lieberman, Daniel E.; Venkadesan, Madhusudhan; Werbel, William A.; Daoud, Adam I.; D'andrea, Susan; Davis, Irene S.; Mang'eni, Robert Ojiambo; Pitsiladis, Yannis (2010). "Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners". Nature. 463 (7280): 531–5. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..531L. doi:10.1038/nature08723. PMID 20111000. S2CID 216420.

- "APMA Position Statement on Barefoot Running". American Podiatric Medical Association. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- "Foot Care". American Diabetes Association. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "The best running shoe may be nature's own: study". Reuters. 27 January 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Divert C., Mornieux G., Freychat P., Baur H., Mayer F., Belli A., "Mechanical comparison of Barefoot and Shod Running." International Journal of Sports Medicine 26.7. 2005; 593–598

- Hersher, Rebecca (27 January 2010). "Study finds barefoot runners have less foot stress than shod ones (w/ Video)". PhysOrg. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Hollander, Karsten; Liebl, Dominik; Meining, Stephanie; Mattes, Klaus; Willwacher, Steffen; Zech, Astrid (July 2019). "Adaptation of Running Biomechanics to Repeated Barefoot Running: A Randomized Controlled Study". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 47 (8): 1975–1983. doi:10.1177/0363546519849920. ISSN 1552-3365. PMC 6604239. PMID 31166116.

- Futrell, Erin E.; Jamison, Steve T.; Tenforde, Adam S.; Davis, Irene S. (September 2018). "Relationships between Habitual Cadence, Footstrike, and Vertical Load Rates in Runners". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 50 (9): 1837–1841. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001629. ISSN 1530-0315. PMID 29614001. S2CID 4591145.

- Hatala, K.G.; Dingwall, H.L.; Wunderlich, R.E.; Richmond, B.G. (9 January 2013). "Variation in Foot Strike Patterns during Running among Habitually Barefoot Populations". PLOS One. 8 (1): e52548. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...852548H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052548. PMC 3541372. PMID 23326341.

- Bernstein, Lenny (21 January 2013). "'Minimalist' running style may be undermined by new findings from Kenya". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Robbins, S; Hanna A (1987). "Running-related injury prevention through barefoot adaptations". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 19 (2): 148–156. doi:10.1249/00005768-198704000-00014. PMID 2883551.

- Hanson, N.J.; Berg, K.; Deka, P.; Meendering, J.R.; Ryan, C. (2011). "Oxygen cost of running barefoot vs. running shod" (PDF). International Journal of Sports Medicine. 32 (6): 401–6. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1265203. PMID 21472628.

- Michael, Warburton (December 2001). "Barefoot Running". Sportscience. 5 (3).

- Chang, Alicia (22 May 2012). "Barefoot Running Injuries: Doctors See Health Problems Ranging From Stress Fractures To Pulled Calf Muscles". HuffPost. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Kerrigan, D. Casey; Franz, Jason R.; Keenan, Geoffrey S.; Dicharry, Jay; Della Croce, Ugo; Wilder, Robert P. (2009). "The Effect of Running Shoes on Lower Extremity Joint Torques". PM&R. 1 (12): 1058–63. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.09.011. PMID 20006314. S2CID 19281815.

- Doheny, Kathleen. "Running Shoes: Hazardous to Your Joints?". WebMD. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Hendrick, Bill. "Barefoot Running Laced With Health Benefits". WebMD. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Richards, C E; Magin, P J; Callister, R (2009). "Is your prescription of distance running shoes evidence-based?". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 43 (3): 159–62. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.046680. PMID 18424485. S2CID 1962544.

- McCaw, Steven T.; Heil, Mark E.; Hamill, Joseph (2000). "The effect of comments about shoe construction on impact forces during walking". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 32 (7): 1258–64. doi:10.1097/00005768-200007000-00012. PMID 10912891.

- Hsu, Jeremy (27 January 2010). "Long-Awaited Barefoot Running Study Finds Sneakers Are Harmful". Popular Science. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Mailler, E; Adams, B (August 2004). "The wear and tear of 26.2: dermatological injuries reported on marathon day". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 38 (4): 498–501. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2004.011874. PMC 1724877. PMID 15273194.

- "Running Injury Risk Using Minimalist Shoes is Influenced by Training Distance and Body Mass". OrthoConsult. 4 February 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Lovett, Richard A. (April 2010). "Much Ado About Minimalism". Running Times. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Winters, Dan (November 2010). "Is Less More?". Runner's World. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- "Vibram FiveFingers Named A "Best Invention of 2007" By Time Magazine". trailspace.com. 12 November 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Gauthier, Al. "Review – Vibram FiveFingers KSO Trek". Living Barefoot. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Cortese, Amy (29 August 2009). "Wiggling Their Toes at the Shoe Giants". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Nike Free 5.0 Running Shoes Review". Running Shoes Guru. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- "Saucony Progrid Kinvara Running Shoe Review: Runner's World". Runner's World. 15 February 2008. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- Jhung, Lisa (May 2011). "Saucony Minimalism". Runner's World. Archived from the original on 9 May 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- "Furry sock shoes designed for walking, running and sports". Gizmag.com. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- Quinn, Elizabeth (4 March 2011). "Barefoot Running Shoes". About.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Ukman, Jason (30 June 2011). "Army bans use of 'toe shoes,' citing image concerns". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Unclassified Communication". United States Navy. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Bacon, Lance M. (29 August 2011). "'Toe shoes' get the boot, Army-wide". Army Times. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Mirshak, Meg (19 July 2012). "Minimalist-style shoes mimic running barefoot". Augusta Chronicle. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Vibram 'Barefoot' Sneaker Maker Sued Over Claims". ABC News. 13 July 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Dye, Jessica (18 June 2012). "Adidas sued over 'barefoot' running shoe claims". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Rovell, Darren (19 June 2012). "Minimalist Running Shoes Are The Next Target in Court". CNBC. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Polk, Andy. "Vibram, 'Barefoot Running Shoe' Company, Settles Multi-Million Dollar Lawsuit". Retrieved 23 December 2022.

Further reading

- Mukharji, Ashish (2011). Run Barefoot Run Healthy: Less Pain More Gain for Runners Over 30. Heterodox Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0983035404.

- Richards, Craig; Hollowell, Thomas (2011). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Barefoot Running. Penguin Group USA. p. 352. ISBN 978-1-61564-062-1.

- Sandler, Michael; Lee, Jessica (2010). Barefoot Running: How to Run Light and Free by Getting in Touch with the Earth. RunBare Company. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-9843822-0-0.

External links

- Biomechanics of Foot Strikes & Applications to Running Barefoot or in Minimal Footwear

- Are we born to run? Archived 16 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, a video presentation by Christopher McDougall.

- Impact characteristics in shod and barefoot running

- Vibrams five-fingers v-train cross training shoes Shoes for muddy trails