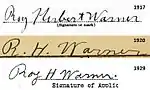

Roy H. Warner

Roy Herbert Warner (13 March 1895 – 11 July 1942) was an American farmer, navy sailor, army soldier, army pilot, airmail pilot, Royal Air Force pilot, and one of ten recipients of the Airmail Flyers' Medal of Honor.

Roy Warner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Roy Herbert Warner March 13, 1895 Vulcan, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | July 11, 1942 (aged 47) Montreal, Quebec, Canada |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Abe |

| Occupation | Aviator |

| Spouse | Fern Viola Gallagher (1921) |

| Awards | Airmail Flyers' Medal of Honor (1935) |

| Signature | |

| |

Early years

Warner was born March 13, 1895, in Vulcan, Michigan. He was the second of three children born to Walter H. Warner of Novesta, Michigan, and Sarah J. Little of Ontario, Canada. Warner had two sisters—Lela, the elder and Eliza, the younger. In 1900 Warner's family was in Brainerd, Minnesota, living with his father's sister and her family while his father worked as a log scaler. None of the children were in school at that time.[1] In 1910 his family moved to Denver, where his father worked as a gold miner.[2] In 1911 his father went to Mexico to mine for gold; the family stayed in Ada, Oklahoma.[3] By mid-1917 Warner was working for himself as a farmer in Winfield, Montana, when he registered for the draft.[4]

Military

Warner served in both World War I and World War II. He enlisted on April 25, 1918, from Winifred, Montana.[5] He served on board the destroyer USS Ingraham (DD-111) as a Fireman 3rd class in the European Theater during World War I. Upon returning to the Brooklyn Navy Yard on December 28, 1919, Warner transferred to the USS Rapidan (AO-18) as an Oiler. By January 21, 1920, Warner was in the Brooklyn Naval Hospital.[6] He was honorably discharged on February 24, 1920.[7] Warner joined the United States Army Reserve and learned to fly after being trained by Utah aviation pioneer Alexander Raymond "Tommy" Thompson, and made his first solo flight in November 1926 at Salt Lake City, Utah.[8]

Career

During a brief employment for the Aero Corporation of Utah (ACU), Warner and fellow ACU pilots Howard Sweet and Raymond L "Ray" Peck (owner of the largest garage in Salt Lake City at the time) were invited to Ogden municipal airport on June 30 to participate in the Air Jubilee and the arrival of their first airmail.[9] Warner and Peck would go on to work for Tommy Thompson when he opened his Flying Service, and Peck, as co-owner, would continue to operate that business after Thompson died in an airplane crash in 1937.

Trouble in the sky

On a personal flight from Salt Lake City to Reno on July 15, 1928, Warner ran into some trouble and was forced to make an emergency landing. He spotted a field to land in and made for it. He had to miss a group of dairy cows on the John Dotta dairy farm just north of Lovelock, Nevada. Warner managed to miss the cows and jump a six-foot canal, but his plane struck a fence, causing it to flip over on its top. He escaped unharmed but his plane was a complete wreck. He walked to Lovelock and found some help and a truck, returning to the craft to take the motor, which was then hauled back to town to be shipped back to Salt Lake City. He burned the remains of the plane on the spot and then continued on to Reno by train.[10]

Another fire

Warner was working for the Boeing Airplane Transport Company on May 21, 1929, flying as co-pilot with chief pilot Hugh Barker in a tri-motor Boeing 80A loaded with mail and passengers. They left Salt Lake City at 9:25 p.m. on May 21 with eight passengers, and had just left Elko, Nevada, where one passenger deplaned. They had taken off and were en route to Oakland, California, where they were due to arrive at 4:00 a.m., but just a few minutes out of Elko the left engine failed and flames ignited the left wing. They were at about 2,000 ft (610 m) when a fire broke out and they had no time to drop flares to light a landing area. Pilot Barker dove the plane and was able to make a smooth landing without any lights. Warner opened the cabin door before the plane came to a stop and the passengers escaped safely. The plane and everything on board was quickly a smoldering pile of rubble, but the seven passengers and two pilots escaped without injury. Several cars were dispatched to the scene to bring the pilots and passengers back the five miles to Elko.[11]

The passengers were: E.J. Read, Mr and Mrs Lewis, C. C. Richardson, B. E. Taylor, Charles Walker and R. M. Scherrit. They boarded another plane in Elko to be taken on to Oakland, the original destination.

Air mail pilot

Warner submitted an application to the Post Office Department for a Certified Aviation Management (CAM) certificate on November 15, 1929, allowing him to fly as primary pilot carrying airmail. Warner listed his prior employment as a pilot with Aeromotive Service Inc. (Aero Corporation of Utah as noted in other newspaper articles), Thompson Flying Service, and Boeing Air Transport Company, all of Salt Lake City. He had flown as "co-pilot" or as a reserve with Transport License number 4086 and logged more than 1,200 hours of flying time. After filing his application, Warner started working for Varney Air Lines flying between Salt Lake City, Utah, and Pasco, Washington, via Boise, Idaho, on CAM-5.

Emergency landing

On a night flight from Boise, Idaho to Pasco, Washington on August 22, 1930 (2:10 a.m.), while over the wooded mountains of Oregon near Durkee, Oregon, Warner suddenly became aware of the strong smell of gasoline. While choking from the fumes, Warner pointed the nose of the plane toward the emergency field at Baker, Oregon just thirty miles to the east. Warner knew that if he cut the throttle to the motor it would back-fire, turning his airplane into a ball of fire. He almost lost consciousness twice and knew fire was inevitable but it came sooner than he expected. Just four miles from Baker Airport, fire broke out. The right wing was nearly burnt through and flames began to creep up the control stick, searing his hand. From an altitude of 7,500 ft (2,300 m) he dove his plane and set it down just a quarter mile from the municipal landing field while managing to keep it "right side up." Quick thinking allowed him to get all fourteen pouches of airmail out of the plane before it was completely engulfed in flames. Fortunately, there were no passengers on this flight and he managed to make it out with just a cut over his right eye from the landing, and minor burns to his hand. After being checked out by a physician, Turner and the mail left with pilot Joe P Livermore to Pasco with only a slight delay of the scheduled flight.[12]

Dive on Ustick, Idaho

During another night flight, for United Airlines on CAM-5, Warner was en route to Portland from Boise, just after midnight on March 21, 1933. While over the Boise suburb of Ustick, Warner spotted a flash in the distance about a mile off to his left. He turned to investigate and spotted a house on fire. Warner noticed there was no one around so he began to dive his plane on the small village, his motors roaring. He continued making pass after pass until the locals began to turn on their lights and look out their windows. Once he was convinced the fire was spotted, and people began to emerge from their homes in night clothes, Warner waved goodbye and continued on to Pasco, the first stop on his route. On this night, thanks to Warner, aged resident and farmer Mr. Charles Julius Kromei and many of his belongings were saved, but his home was destroyed.[13]

Medal from the President

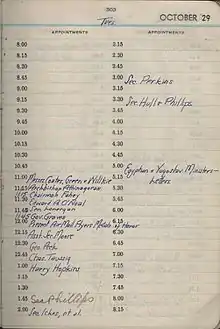

Warner was one of seven airmail pilots awarded the Airmail Flyers’ Medal of Honor for extraordinary achievement by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on October 29, 1935, at a ceremony (12:00–12:15) in the White House. Each pilot had saved mail in hazardous landings.

Present at the ceremony were: President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt; Postmaster General, James A Farley; Lewis S Turner of Fort Worth, Texas; James H Carmichael, Jr. of Detroit, Michigan; Edward A Bellande of Los Angeles, California; Gordon S Darnell of Kansas City, Missouri; Willington P McFail of Murfreesboro, Tennessee; Roy H Warner of Portland, Oregon; and Grover Tyler of Seattle, Washington. Warner's deed was chronicled on the well known Wheaties cereal box cover as part of a series of eight box covers regarding the feats of pilots awarded the Air Mail Flyers Medal of Honor.

Medal citation

For extraordinary achievement while piloting an air mail plane on the night of August 22, 1930, on a flight from Boise, Idaho, en route to Pasco, Washington. Near Baker, Oregon, while flying at an altitude of about 7500 feet, Pilot Warner felt gasoline spraying against his face and immediately headed for an emergency landing field. Realizing that if he throttled his motor a backfire might ignite the gasoline fumes, he attempted a steep power dive. The fumes came back into his face, however, causing nausea and strangulation, making a side slip necessary. When the landing lights flashed on the ground, he cut his motor to land and the plane burst into flames. With his trousers afire and his right hand burning from handling the "stick," Pilot Warner continued to control the plane, but when the fabric burned off the right wing the ship went into a spin and landed on one wing, bounced into the air and hit again right side up. Pilot Warner climbed out of the flame enveloped cockpit and jumped clear of the fire and smoke to get fresh air. Nearly suffocated and sick from nausea, Pilot Warner thought of the mail, returned to the burning plane, opened the door, removed and threw all of the mail to safety. He completed the task and ran from the ship only a few second before the gasoline tanks exploded. (Signed) James A Farley, Postmaster General"[14]

Later life

Affidavit

On December 18, 1936, just three days after a United Air Line twin-engine Boeing plane was lost with 12 persons on board near Saugus, CA, another plane was reported missing. This was Northwest Airlines westbound Flight 1. The Lockheed 10A Electra (NC 14935) piloted by Joseph P Livermore and co-pilot Arthur Haid was en route from Chicago to Seattle with ten intermediate stops. It had departed Missoula, Montana, at 12:33 a.m. bound for Spokane, Washington. At 1:59 a.m. pilot Livermore reported that they were not receiving range signals and the plane was picking up ice. They requested the radio personnel stationed at Spokane to listen for the flight in the skies over the range station. Spokane could not hear the airplane and confirmed that the signal generator was working properly. Livermore next radioed that they were over a town with a large number of lights and asked Spokane to check his position as they could not stay up much longer due to the ice. At 3:19 a.m. a telephone operator confirmed that a plane was circling Elk River, Idaho, and pilot Livermore was notified of his location. He then radioed they were now on course on the "south leg" of Spokane "heading north." No further contact was made. On December 26 the wreckage of the plane was found about 400 ft (120 m) from the top of a mountain known as Cemetery Ridge in the Saint Joe National Forest near Kellogg, Idaho. It was determined the aircraft had impacted while in level flight and was destroyed catching fire; the two pilots were killed instantly. The weather that evening had been reported as light rains at low level, light snow squalls, and icing conditions and it was believed there was possible fog in the area. A subsequent investigation found no failures in the aircraft, but noted the possibility of instrumentation problems. Livermore had gone north rather than the standard western route, possibly to shorten the time in the storm, and may have become lost, being unfamiliar with the area, when they flew into the mountain top at 3:23 a.m., just four minutes after their last transmission.

The Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) headed by President David L. Behncke took up the charge that airlines were pressuring their pilots to fly in unrealistically dangerous conditions. The charge was initiated by Livermore's widow who took action immediately after the disappearance of the flight, sending a notarized statement to the Department of Commerce. She stated that her husband had been threatened with termination if he did not continue to fly in bad weather conditions, against his better judgment in what would be his last successfully completed flight five days prior to his death. Livermore was one of the old pilots who relied on flying by sight and landmarks. He did not like using the new radio signal system, and several other pilots refused to fly with him because of that. His refusal to use the new system ended up putting him in an area he was unfamiliar with and resulted in the crash.

Warner had also provided a deposition to the ALPA regarding his own experience with the airlines pressuring pilots to fly in dangerous conditions. However, having recently been terminated by Northwest Airlines, Warner's statement was seen as biased toward the airline.

World War II and death

In mid-1941 Fern filed for divorce, and on June 16, 1941, her request was granted by the Reno, Nevada court system.[15] Warner applied for a passport, which was approved on February 22, 1941. He then moved to Canada and began to fly for the Royal Air Force (RAF). While flying for the RAF Ferry Command in Canada, Warner was admitted to the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, where he died July 11, 1942, of carcinomatosis (multiple cancer tumors). His body and personal effects were returned to the United States on July 31, 1942, to his mother, Sarah J Williams, in Fillmore, California.[16] He was interred at Bardsdale Cemetery.

References

- 1900 U S Census (Line 91 - 95 ed.). Brainerd, Crow County, Minnesota: US Government. June 11, 1900. p. Sheet 9.

- "1910 U S Census". Denver City, Denver County, Colorado. T624 116 (Lines 18 - 2-): 1A. April 15, 1910.

- "Department of State, Bureau of Citizenship". Certificate of Registration of American Citizen. 4 (Citation 30075): 168. January 12, 1912.

- "World War I draft registration". Fergus County, Draft Registration. 25-2-4-A (Winifred, Fergus Co., Montana): Form 1, No. 19. June 5, 1917.

- "WW1 Draft Card". Fergus County Registration Card. Form 1, No. 19 (25-2-4-A). June 5, 1917.

- "1920 U S Census". Brooklyn Naval Hospital, Kings County, New York. D1-578 (Form 9-137): Sheet No. 2B, Line 72. January 21, 1920.

- "Application for Headstone or Marker". War Department, OQMG. Form No. 623, 1 July 1942 (16-11453-1 GPO). August 6, 1943.

- "USPS (CAM) Application". Post Office Department. Second Assistant Postmaster General, Washington (Form 2707). November 15, 1929.

- "City invites western pilots". No. Page 6. The Ogden Standard Examiner. June 15, 1928.

- "Pilot wrecks his plane". No. Page 6. Reno Gazette Journal. July 16, 1928.

- "Nine saved as burning plane lands at Elko". No. Front Page. Daily Capital Journal. May 22, 1929.

- "Airman saves mail as flames destroy plane". No. Front Page. The Bend Bulletin. August 22, 1930.

- "Airmail flier wakes farmers as fire rages". No. Front Page. The Post Register. March 21, 1933.

- McCarty, Philip R (January 1966). "The Airmail Flyer's Medal of Honor". The Airpost Journal. 67 (1): 9–18.

- "Decrees Granted". No. Page 6. Reno Gazette Journal. June 16, 1941.

- "American Foreign Service, Report of the Death of an American Citizen". Division of Foreign Service Administration. Consult Section XIII-7 and XIII-8 (Form No. 192 Foreign Service (Corrected June 1941)): 342.113. August 6, 1942.

External links

- H.R.101

- Public law 661

- Public law 91-375 (12 Aug. 1970)

- Apropriations A-35875 April 2, 1931, 10 Comp.Gen.543 Archived April 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- JOMSA article 1990 Vol. 141.3.13

- JOMSA article 1953 May - Aug

- JOMSA article 1966 Vol. 17.12.7

- NASM Medal image (Silver) Archived April 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- NASM Medal image (Bronze) Archived April 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Chicago Tribune, 3 Nov 1935

- USS Ingraham (DD-111)

- USS Rapidan (AO-18)

- Salt Lake City and early aviation

- Boeing Air Transport Co. timetables

- Boeing Air Transport CAM-18

- Boeing model 80

- Museum of Flight 80A-1

- ALPA, Chapter 5: The Livermore affair

- Department Of Commerce, report of the accident board, Flight 1

- Roy H. Warner at Find a Grave