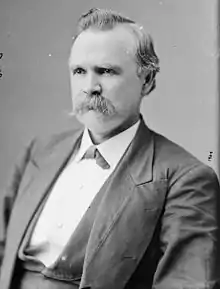

Roger Q. Mills

Roger Quarles Mills (March 30, 1832 – September 2, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician. During the American Civil War, he served as an officer in the Confederate States Army. Later, he served in the U.S. Congress, first as a representative and later as a senator.

Roger Quarles Mills | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Texas | |

| In office March 30, 1892 – March 3, 1899 | |

| Preceded by | Horace Chilton |

| Succeeded by | Charles A. Culberson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Texas | |

| In office March 4, 1873 – March 29, 1892 | |

| Preceded by | District created |

| Succeeded by | David B. Culberson |

| Constituency | At-large (1873–75) 4th district (1875–83) 9th district (1883–92) |

| Member of the Texas House of Representatives | |

| In office 1859-1860 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 30, 1832 Todd County, Kentucky, US |

| Died | September 2, 1911 (aged 79) Corsicana, Texas, US |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States of America |

| Branch/service | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | 3rd Texas Cavalry Regiment |

| Commands | 10th Texas Infantry Regiment Deshler's Brigade |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

As the top Democrat on the powerful United States House Committee on Ways and Means during the first Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison administrations, Mills was the leading advocate in Congress for trade liberalization. He was ultimately unsuccessful in passing any major tariff reduction and, after Republicans won control of the House on a pro-tariff platform, was unsuccessful in blocking the McKinley Tariff of 1890. He ran for Speaker after Democrats regained the House in 1891 but lost to Charles F. Crisp.

Early life

Born in Todd County, Kentucky, Mills attended the common schools and moved to Texas in 1849. There, he studied law, passed the bar, and began practicing in Corsicana at the age of 20 after the Texas legislature made an exception to the usual age requirement.[1] He was a member of the Texas House of Representatives from 1859 until 1860, when he enlisted in the Confederate States Army. He served throughout the Civil War and took part as a private in the Battle of Wilson's Creek, and as a colonel commanded the 10th Texas Infantry Regiment at Arkansas Post, Chickamauga (where he commanded the brigade of Gen. James Deshler during part of the battle), Missionary Ridge and the Atlanta Campaign.

U.S. Representative

He was then elected as a Democrat to the US House of Representatives and served from 1873 to 1892. In 1891, Mills was a candidate in the Democratic caucus for Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, but he was defeated by Charles F. Crisp (1845–1896) of Georgia.

In the 1880s, when Prohibition sentiment was rising in Texas, Mills refused to make any political concessions. Reportedly, he declared in one speech, "If lightning were to strike all the drunkards, there would not be a live Prohibition party in Texas." (Mills claimed to have been misquoted and that he had said "there would not be many [members of the party] left.") Elsewhere, he was said to have vowed, "A good sluice of pine top whiskey would improve the morals of the Dallas [Prohibition] convention and the average Prohibitionist." (Mills again offered a correction and insisted that he had not used the words "average Prohibitionist.").[2]

Mills quickly became noted as one of the ablest, if hottest-tempered, debaters on the Democratic side of the House and was commonly agreed.to be a man "possessed of the demon of work." The reporter Frank G. Carpenter described him as true as steel and unpretentious in dress: "He is tall, straight and big chested," he wrote in 1888. "The distance between the top button of his high vest and the small of his back is longer than the width of the shoulders of the ordinary man, and he has a biceps which, if put into training, would knock down an ox. He is a fighter, too, and goes into this Congressional struggle with a brain trained to warfare.... He is a successful man, and one who inspires confidence."[3]

Chairmanship of the Committee on Ways and Means

Mills had made the tariff his special study and long been recognized as one of the leading authorities on the Democratic side. After the defeat of House Ways and Means Committee Chairman William Morrison in the 1886 election, Mills became the next chair of the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means when the 50th Congress met. His selection, according to Ida Tarbell, a historian on the tariff, "was a red rag to the high protectionists, for Mr. Mills was an out-and-out free trader."[4] Debate over the tariff issue had been thrust upon the United States by President Grover Cleveland in his annual December message to Congress on December 6, 1887.[5] He requested for Congress to pass a drastic reduction of the tariff on many manufactured goods to promote trade and reduce the cost of living for ordinary citizens.[6] Indeed, Chairman Mills, using the Walker Tariff of 1846 as a guideline, had been drafting a bill since September 1887 that would address several of the proposals included by Cleveland in his December message. As it turned out, most of Mills's work went for naught, as he later explained: "When I got to work with my brethren on the bill I found that it would not go, and I had to abandon my ad valorem tariff bill. The schoolmaster had not been sufficiently around, to bring our people back to the Democratic principle of taxation as to value."[7] The bill became known as the "Mills Tariff Bill of 1888."[8] The Mills Bill was reported out of the Ways and Means Committee in April 1888.

The bill provided for a reduction of the duties on sugar, earthenware, glassware, plate glass, woolen goods and other articles; the substitution of ad valorem for specific duties in many cases; and the placing of lumber (of certain kinds), hemp, wool, flax, borax, tin plates, salt and other articles on the free list.[8] The bill looked likely to split the Democratic Party. Just two years previously, the high tariff wing of the Democratic Party had been able to muster 35 votes in the House.[9] However, the Mills Bill had now become so highly partisan that when the bill was passed by the Democratic House on July 21, 1888, only four Democratic representatives voted against it.[9] The high-tariff wing of the Democratic Party had largely been wiped out by the passage of the Mills Bill of 1888.

Although the Mills Bill passed the House, the Republican Senate amended it heavily, and it never passed into law. Instead, it became the chief issue in the 1888 presidential election. Critics warned that American manufacturers could not compete against the flood of manufactured goods from Britain, and campaign crowds marched the streets chanting, "No! no! no Free Trade!" (However, the bill was not anything close to being a free-trade measure but offered an average reduction of only seven percent, and many items were left untouched.) "If Mills of Texas does not shut down, many other mills will have to," a California newspaper warned.[10] In the 1888 election, Republican Benjamin Harrison, a strong high-tariff supporter lost the popular vote nationwide to Cleveland, but Harrison managed to narrowly win both swing states of New York and Indiana and so won the presidency in the Electoral College-based, largely by the tariff issue.

1891 speakership candidacy

Mills was known to have aspirations to be speaker after the retirement of John G. Carlisle. In late 1891, with the House returning to Democratic control, the Texas representative put himself in the running against Representative Charles Crisp from Georgia. Before the caucus met, Mills had 120 votes pledged to him, and if all of them had kept their word, he would have won, but only 105 did so on the final, thirtieth, ballot, against Crisp's 119. The reason, apparently, was that Mills refused to make deals.

Some two dozen members wanted a guarantee of specific committee assignments in return for their support, but Mills would have none of it. Reportedly, Representative William Springer of Illinois, who was also contending to be speaker, offered to drop out if Mills would appoint him chair of Ways and Means and was told gruffly to put his offer in writing. As a result, the night before the caucus voted, Springer withdrew on Crisp's behalf, and Crisp made him chairman of Ways and Means, subsequently. To Representative Tom Johnson of Cleveland, one of Mills's most earnest backers, the Texas representative's conduct looked like political insanity. "I wish you wouldn't be a fool," he burst out; "give me two chairmanships and ask me no questions and I will elect you on the next ballot." He got only a shake of the head in reply.[11]

Mills's problems, however, were deeper than his failure as a horse-trader. For one thing, his irascibility and the regularity with which he lost his temper made many of his party friends worry that he lacked the self-control necessary to be speaker. The party's job would be hard enough without what one newspaper called Mills's "tempestuous style."[12] His selection would have signaled that the Democratic Party's main agenda would be lowering the tariff drastically. Crisp was much less associated with tariff reform than with the coinage of free silver, which, to most Southern Democrats, was the top issue by late 1891. Among the Silver Democrats, it did not help Mills to have former President Cleveland's backing or, among those favoring the presidential nomination of Cleveland's rival, Senator David Bennett Hill of New York, that Hill threw his weight behind Crisp's candidacy, too.[13]

Mills took badly to his rejection, issuing a letter that was quickly made public that the Democratic Party had been hurt more than he by his rejection as well as threatening that "a large element that has been voting with us [would] abandon us" in the coming election unless those who had defeated him were met with rebuke by their party.[14]

US Senator

Mills was elected to the US Senate from Texas in 1892 to fill the vacant seat of John H. Reagan and continued to serve in that post until 1899.

In 1893, when President Grover Cleveland sought repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, Mills gave loyal support. Silver coinage was popular with both parties in Texas, and Democrats in particular felt that Mills had betrayed them. His action probably cost him re-election in 1898.

Other friends also noticed a change in him. His old colleague and co-worker in tariff reform, former Representative William L. Wilson of West Virginia, wrote in his diary in 1896, "Poor Mills, how he seems to have gone to pieces since the time when he was leading the tariff reform forces in the House, and a welcome and strong speaker on that great issue all over the country. Today he made one of the most extreme and wild jingo speeches in the Senate on the Cuban question that has marked the whole debate. Not less erratic has been his course for two years past on the financial question."[15]

Death and legacy

He died in Corsicana, Texas. Roger Mills County, Oklahoma, was named after him.

References

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Myrtle Roberts, "Roger Quarles Mills," M. A. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1929, pp. 49-50.

- Frank G. Carpenter, in "Washington Critic," January 7, 1888.

- Ida Tarbell, "The Tariff In Our Times" (New York: Macmillan, 1912), p. 155.

- Crapol, Edward P., James G. Blaine: Architect of Empire (S.R. Books Publishing Co.: Wilmington, Delaware, 2000) p. 106

- Nevins, Allan, Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage (Dodd, Mead and Co.: New York, 1933) p. 379

- Nevins, Allan, Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage, p. 372; Myrtle Roberts, "Roger Quarles Mills," M. A. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1929, p. 77.

- Nevins, Allan, Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage, p. 389.

- Nevins, Allan, Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage, p. 393.

- "Salem (Oregon) Daily Statesman," April 4, 1888.

- Myrtle Roberts, "Roger Quarles Mills," M. A. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1929, pp. 96-97.

- "New York Evening Post," November 8, 1890.

- Arthur W. Dunn, "From Harrison to Harding: A Personal Narrative," p. 78; Champ Clark, "My Quarter Century of American Politics" (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1920), 1: 273.

- "San Francisco Examiner," January 9, 1892.

- Summers, ed., "Cabinet Diary of William L. Wilson" (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957), p. 51.

Sources

- United States Congress. "Roger Q. Mills (id: M000777)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-05-04

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mills, Roger Quarles". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Roger Quarles Mills from the Handbook of Texas Online

What shall we do with silver? by Roger Q. Mills, The North American review, Volume 150, Issue 402, May 1890.

What shall we do with silver? by Roger Q. Mills, The North American review, Volume 150, Issue 402, May 1890.