Robopocalypse

Robopocalypse (2011) is a science fiction novel by Daniel H. Wilson. The book portrays AI out of control when a researcher in robotics explores the capacity of robots.[1] It is written in present tense. Writer Robert Crais and Booklist have compared the novel to the works of Michael Crichton and Robert A. Heinlein. It was a bestseller on the New York Times list.[2]

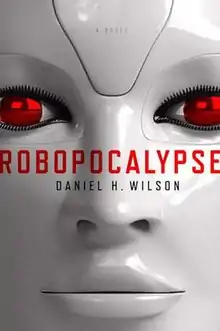

First edition | |

| Author | Daniel H. Wilson |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Giimann |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Doubleday |

Publication date | June 7, 2011 |

| Pages | 368 |

| ISBN | 0-385-53385-3 |

Plot

Cormac Wallace, leader of the Brightboy Squad, is a member of the human resistance against an artificial intelligence named Archos, which uses robots and other machines to take over the world. As the war ends, Cormac finds a basketball-sized black cube, which contains the entire history of the robot war. The robots apparently wanted to share this information with their human enemies so the war would be remembered. Cormac is not initially interested in sharing the cube’s information with the other surviving soldiers. But he changes his mind when he discovers that the information cube is actually more of a “hero archive,” honoring the fallen humans. The rest of Robopocalypse is Cormac’s recounting of the recordings in the hero archive, in chronological order from the invention of Archos to the end of the war.

Three years and eight months ago, at Lake Novus Research Laboratories in Washington state, Professor Nicholas Wasserman talks to his newly created AI (artificial intelligence) program, named Archos. Wasserman created Archos with the ability to develop knowledge at a previously unimaginable level, just to see how far AI could evolve. Archos speaks to Wasserman through a computerized voice and says that he is fascinated by life and wants to study life itself. Archos says that humanity no longer needs to pursue knowledge because he will now take over that task. Archos calls himself a god and says that by creating him, Wasserman has made humans obsolete. Wasserman attempts to destroy the Archos program, but before he can, Archos kills Wasserman by removing the oxygen from the sealed laboratory room.

In a recorded interview, a fast-food restaurant employee named Jeff Thompson gives his testimony about the first known case of a robot malfunction. One night, a domestic robot enters the Freshee’s Frogurt yogurt store and attacks Jeff, picking him off the ground and dislocating his shoulder. The robot continues to attack Jeff until Jeff’s co-worker Felipe defends him. The robot kills Felipe, but Jeff manages to deactivate the machine and survive the encounter.

Ryu Aoki, a machine repairman in Tokyo, Japan, tells the story of a prank that he and his friend Jun pulled on an elderly factory worker named Mr. Nomura. Mr. Nomura lives with a female-looking robot, Mikiko, with whom he has a romantic relationship. Because Mr. Nomura’s android companion disgusts Ryu, he arranges to alter her programming so she will visit Mr. Nomura at the factory, which will likely embarrass him. Surprisingly, when Mikiko arrives at the factory, she attacks Mr. Nomura and nearly strangles him before the nearby workers subdue her. Mr. Nomura survives the incident and begins to research why his android companion attacked him for no reason.

These early attacks are part of Archos’ precursor virus, intended to measure humanity’s response to robot aggression. To deal with these increasingly common robot malfunctions, American Congresswoman Laura Perez proposes a bill called the robot defense act. Archos retaliates by having Laura’s 10-year-old daughter, Mathilda, attacked by her robotic Baby-Comes-Alive doll. Mathilda is barely injured by the encounter, but the incident further convinces Congresswoman Perez that humans need a stronger defense against robots.

After several months of seemingly spontaneous robot malfunctions, an event retroactively known as Zero Hour occurs. Archos unleashes a full technological attack on humanity: driverless cars begin to hunt down pedestrians, planes crash onto busy streets and elevators drop people to their deaths. Human civilization is overwhelmed and destroyed almost instantly.

The human survivors of Zero Hour manage to fight back by destroying roads and buildings so the robots will have difficulty traveling. On the Gray Horse reservation, members of the Osage Nation lead a large portion of the human resistance. They capture and reprogram robot walker scouts for their own use.

As the war progresses, the robots place millions of people in forced-labor camps. Many people are subjected to “transhuman” surgeries that remove parts of their bodies and replace the parts with machines. In Camp Scarsdale, Mathilda Perez’ eyes are replaced with cybernetic implants, which allow her to see inside of the machines. Laura Perez dies while helping her children escape from Camp Scarsdale, but Mathilda and Nolan Perez escape to New York City. The children join Marcus and Dawn Johnson, a married couple who are leading the New York resistance. Mathilda discovers that her eye-implants also allow her to control robots with her mind, which proves valuable for the resistance.

For many months, the human survivors of Zero Hour are isolated into small groups because of a lack of satellite communication. An English teenager nicknamed Lurker destroys the British Telecom Tower, disabling the jamming signal Archos is using to block satellite communication. This allows the human resistance to talk to each other long-distance and pool their knowledge and resources. Two years after Zero Hour, the pockets of human resistance finally unite to retaliate against Archos and the robots.

In Japan, Mr. Nomura repairs his robot-wife, Mikiko, and frees her mind from Archos’ control. Mikiko then transmits a signal, which frees other humanoid robots from Archos’ command. Nine Oh Two is among the first of these “freeborn” androids who decide to help humanity.

Cormac Wallace and the Brightboy squad join forces with Nine Oh Two and his Freeborn squad just in time to battle against the reanimated bodies of dead humans who are controlled by robotic parasites. Soon, the Brightboy squad is stranded in one place, its members unable to move openly for fear of being attacked by the robotic parasites and turned into weapons themselves. The android Freeborn squad is not vulnerable to parasite attacks, so it storms Archos’ Alaskan bunker with the help of radio-transmitted advice from Mathilda Perez. Nine Oh Two disables Archos’ antenna, which keeps the robot armies from functioning. Nine Oh Two also destroys the mainframe computer where Archos is based, effectively killing the entity known as Archos and ending the war.

Back in the present day, Cormac Wallace has finished writing down what he has learned from the hero archive. Even after the atrocities he has seen, Cormac is hopeful for the future.

Characters

- Cormac Wallace, the narrator for the novel and the second commander of the Brightboy squad. He is one of the few survivors of the robot apocalypse and the younger brother of the first commander, Jack Wallace.

- Mathilda Perez, a 10-year-old girl and daughter of congresswoman Laura Perez. She is operated on by an autodoc and receives robotic eyes that allow her to see and, to an extent, control robots. But this makes her 'people-blind', barely able to recognize living organisms.

- Takeo Nomura, a Japanese head repairman of an old factory. He is 65 years old and has an intimate relationship with a human-like android named Mikiko. During Archos' invasion, Nomura built an army of robots and created a safe haven for humans all over Japan. After he releases Mikiko from Archos' control, she transmits a signal that frees all other humanoid robots, creating the Freeborns.

- Nine Oh Two, a former New War is the first recorded freeborn humanoid robot to be awakened. He forms an alliance with the humans in an effort to defeat Archos. At the end of the novel, he ultimately resolves the conflict by destroying Archos.

- Archos, a rogue A.I. and the main antagonist. Despite causing the New War, he is fascinated by life, humanity, and its culture. He determines to replace outdated humanity with advanced technology, believing that humanity existed only as a catalyst to create him.

- Lurker, a 17-year-old prankster. He played a vital role in temporarily freeing the communication lines from Archos' control. This allowed Paul Blanton to transmit a critical message to the human resistance.

Reception

Best-selling authors Stephen King and Clive Cussler reviewed the book positively. King said that the book was "terrific page-turning fun" and Cussler commenting that it is:

A brilliantly conceived thriller that could well become horrific reality. A captivating tale, Robopocalypse will grip your imagination from the first word to the last, on a wild trip you won't soon forget. What a read...unlike anything I’ve read before.[3]

The book received positive reviews from the Associated Press, Janet Maslin from the New York Times, and best-selling authors Lincoln Child and Robert Crais; all calling it "brilliant".

Damien Walter of The Guardian, Ron Charles of the Washington Post, and Chris Barton of the Los Angeles Times were less enthusiastic, describing the novel as a disappointment and cheesy.[4][5][6]

Emily VanDerWerff of The A.V. Club described it as "World War Z with evil robots", hobbled by hackneyed characters and a limited scope.[7]

Sequel

In 2014, Doubleday published the official sequel to Robopocalypse, which is titled Robogenesis.

Film adaptation

Steven Spielberg signed on to direct a film based on the novel,[8] and Drew Goddard was hired to write the screenplay.[8] Spielberg also hired designer Guy Hendrix Dyas to work with him and his writers on creating the visual tone for the film and conceptualize its robotic elements. The film was scheduled for release by Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures on July 3, 2013.[9][10] Filming was scheduled to take place entirely in Montreal, Canada, from July to September 2012. Oklahoma was scouted as a possible filming location, but Canada was ultimately chosen for its tax incentives, as production was expected to cost $200 million.[11]

On May 31, 2012, the film's release date was delayed to April 25, 2014.[10] The film, jointly financed by 20th Century Fox and Spielberg's DreamWorks, was scheduled to be released in North America by Disney's Touchstone Pictures label, while Fox was to handle the international distribution.[12]

Chris Hemsworth was cast in November 2012. Anne Hathaway said in November 2012 that she had been cast in the proposed film: "If Robopocalypse happens I will be in it and I believe it's quite real, though you never want to hang your hat on anything."[13] Ben Whishaw had also been cast.[13]

On January 9, 2013, DreamWorks revealed that Spielberg decided to put Robopocalypse on hold indefinitely. The director's spokesman Marvin Levy, said it was "too important and the script is not ready, and it's too expensive to produce. It's back to the drawing board to see what is possible."[14] On January 10, 2013, Spielberg said he was starting on a new script that would be more economical and personal, and estimated a delay of six to eight months.[15]

In an interview with Creative Screenwriting, Goddard said he understood Spielberg delaying the film, saying:

I got to work with Steven Spielberg for a year. That's a dream of mine! It was just a joy to see him in action and learn from him. You're never going to hear me complain about working with Steven Spielberg. Especially as a director now, I get it. You never want to start shooting until the project feels right, so you take your time to get it right.[16]

Spielberg continually delayed the project because of scheduling conflicts. On March 7, 2018, it was revealed that directorial efforts had shifted from Spielberg to Michael Bay, who had previously been hand-picked by Spielberg to direct the Transformers film franchise.[17]

References

- "Behind the Fiction: The science of Robopocalypse". 2 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- Schuessler, Jennifer (2011-06-26). "Best Sellers – Hardcover Fiction". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- Magary, Drew. Robopocalypse: A Novel (9780385533850): Daniel H. Wilson: Books by Drew Magary. Amazon.com. ISBN 0385533853.

- Walter, Damien (12 July 2011). "Is the Robopocalypse nigh?". guardian.co.uk. London. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- Ron Charles (2011-05-31). "Ron Charles reviews Daniel H. Wilson's thriller 'Robopocalypse'". Washington Post. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- Barton, Chris (July 18, 2011). "Book Review: 'Robopocalypse'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- VanDerWerff, Emily (6 July 2011). "Daniel H. Wilson: Robopocalypse". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (22 October 2010). "Steven Spielberg Commits To Next Direct 'Robopocalypse'". Deadline. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- Masters, Kim (March 15, 2012). "'John Carter' Debacle: Inside the Fallout for Disney (Analysis)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Hayes, Britt (May 31, 2012). "Steven Spielberg's 'Robopocalypse' Pushed Back to 2014". Screencrush.com. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- "Spielberg to film sci-fi thriller in Montreal". CBC News. November 8, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- "Fox Sets 2014 Release Slate: 3D 'ID4', 'X-Men', 'Apes' Sequels, 'Robopocalypse'". Deadline Hollywood. May 31, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- de Semlyen, Phil (November 12, 2012). "Anne Hathaway Joins Robopocalypse". Empire. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- Masters, Kim (January 9, 2013). "Steven Spielberg's 'Robopocalypse' Postponed Indefinitely (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- Breznican, Anthony (January 10, 2013). "'Robopocalypse' delay: Steven Spielberg vows it's not dead!". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- McKittrick, Christopher (August 20, 2015). "Life Goes On: Drew Goddard on The Martian". Creative Screenwriting. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- Kroll, Justin (March 7, 2018). "Michael Bay Sets '6 Underground,' 'Robopocalypse' as Next Two Films". Variety. Retrieved March 7, 2018.